Early warning: How Iraq can adapt to climate change

Summary

- Iraq is at high risk of suffering the worst effects of the climate crisis, including soaring temperatures and acute water scarcity.

- As land suitable for farming shrinks and rural jobs disappear, ordinary Iraqis are moving to cities in search of work. This increases pressure on services, pushes up food prices, and exacerbates social tensions, leading to protests and even violence.

- Iraq’s weak internal governance prevents it from improving water management, managing inter-provincial and inter-tribal conflict, and attracting investment and expertise to create new green-economy jobs and adapt to the changing climate.

- Public awareness of climate risks is growing, but too few political leaders prioritise the issue.

- Iraq has long struggled to reach agreement on water issues with upstream states Turkey and Iran, which are building dams that affect supply to Iraq; they also believe that Iraq manages water badly. Similar issues complicate relations between Baghdad and the Kurdistan region.

- Iraqis and Europeans should work together to improve Iraq’s poor governance and consider measures such as establishing an ‘early warning’ system about potential conflict arising from climate effects.

Introduction

A series of dramatic events in the last six months brought home the reality, and dangers, of climate change to the Iraqi public. Nine dust storms swept through the country in a period of only eight weeks, leading to the closure of government offices and airports, stifling economic activity, and hospitalising thousands of people. Cells of the Islamic State group (ISIS) took advantage of the reduced visibility caused by the storms to launch attacks on Iraqi security forces.

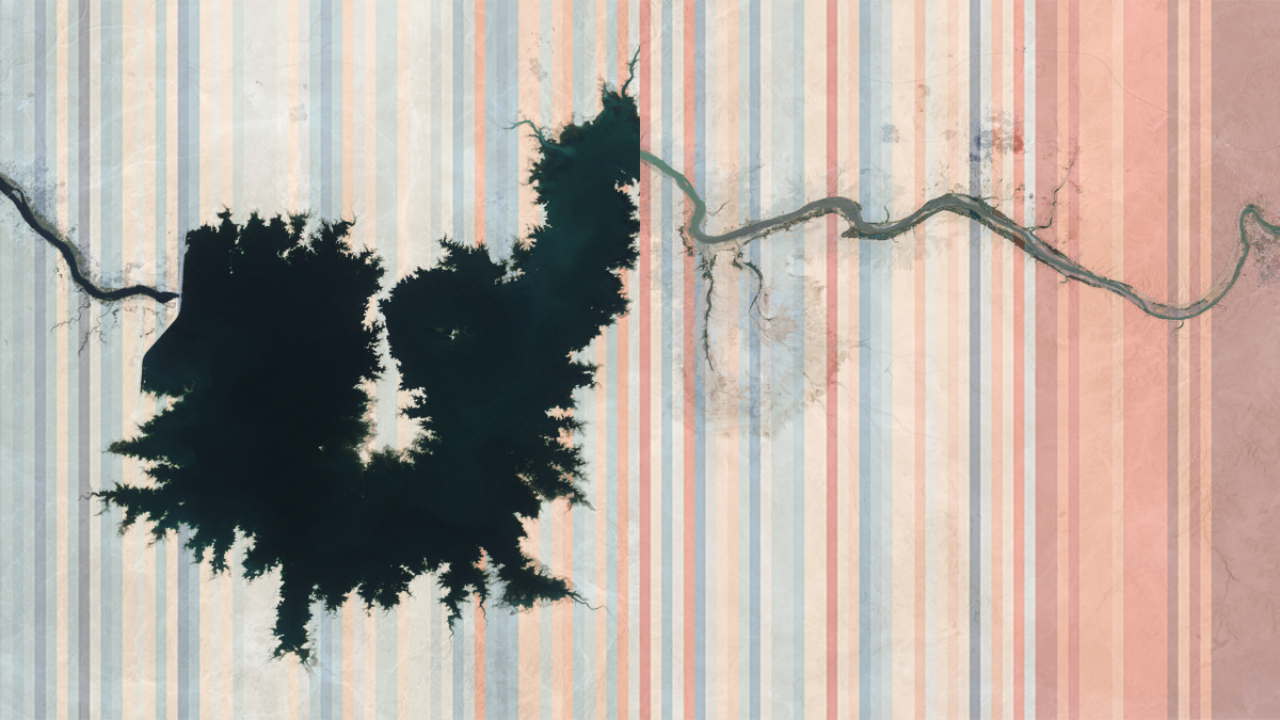

At the start of 2022, the news that Lake Sawa in Muthanna province had completely dried up led to an outpouring of grief and nostalgia as local people and commentators lamented the impact on livelihoods and on the identity of the province. Further alarming stories have followed about critically low water levels in Lake Hamrin in Diyala province and about increasing pollution in Lake Razzaz in Karbala province.

And back in 2018, water quality in Basra declined substantially as rising water levels in the Persian Gulf combined with reduced water flows from upstream rivers and diminished rainfall to increase salinity in the city’s Shatt al-Arab river. This caused the hospitalisation of close to 120,000 people, and led to thousands of citizens joining mass protests against local and federal government authorities. Security forces and politically affiliated armed groups responded with violence, killing at least 31 people and injuring hundreds of others. The government’s poor handling of the crisis ended prime minister Haidar al-Abadi’s bid for a second term in office, damaged the legitimacy of state institutions, and enabled armed groups to launch a campaign of targeted assassinations against activists and protesters.

Such events have finally brought the issue of climate change into Iraq’s political debate – but the country’s leaders are yet to take meaningful action. This is despite the fact that the medium- and long-term outlook for Iraq and climate impacts is extremely serious. In 2019, a UN report classed Iraq as the world’s fifth most vulnerable country in terms of availability of water and food, and exposure to extreme temperatures. Temperatures in the country are increasing up to seven times faster than the global average, while annual rainfall is predicted to decrease by 9 per cent by 2050. At the same time, the country faces a rate of population growth that is twice the global average, at 2.25 per cent a year; its population is set to reach 50 million by 2030 and 70 million by 2050.

These dynamics are driving significant rural-to-urban migration, placing enormous pressure on limited services and employment opportunities in urban areas, triggering social unrest, and fuelling inter-provincial and inter-tribal competition and conflict. In some cases they have enabled extremist groups to gain footholds in impoverished rural areas. Iraq’s inadequate governance, anaemic private sector, and consequent lack of foreign direct investment hinders the country from taking more concerted action to address both the causes and effects of climate change. Its poor internal governance also leads to wasteful water management, placing it on a weaker footing vis-à-vis upstream countries Turkey and Iran, which are building dams that worsen the situation in Iraq.

Iraq urgently needs to agree, and allocate significant funding towards, a working climate action policy agenda. Europeans can offer their support in a number of ways – certainly on the technical front, but also by persuading Iraq’s political leaders of the benefits of such an agenda not only for addressing the impacts of the changing climate but also for improving internal governance and diversifying the country’s economy.

The politics and economics of climate change in Iraq

Politics

Iraq is currently trapped in a period of political paralysis: nine months on from a parliamentary election in October 2021, no new government is yet in place. Recently, turmoil roiled the political scene when members of the Sadrist Movement – the most successful bloc in the election – resigned from parliament en masse. Despite Iraq benefitting from a revenue windfall in a period of high oil prices, until a new government is in place the state may legally be unable to pass a new budget to distribute funds – whether to address climate change or other issues that require long-term investment and commitment.

Even when a new government eventually takes office, it is far from clear that climate action will receive the high-level support and funding it requires. Political competition is intense, particularly between armed Shia parties – which govern some of the areas most affected by climate change but prioritise other issues. This political chaos is underlain by a weak understanding of climate change among the country’s ruling elite.

Some important voices are making the case for climate investment, including at the very top of Iraqi politics. On the initiative of President Barham Salih, in November 2021 the federal government adopted the Mesopotamia Revitalisation Project. This project maps out for the first time an ambitious plan for addressing the most critical impacts of climate change in the country. President Salih is a passionate advocate of climate change adaptation. In an interview with the author, he said: “the scale of the problem [climate change] is so severe as a driver of conflict and instability that it is gradually becoming an issue that Iraqi politicians find worth talking about.”[1]

His proposals include a water management initiative, a reforestation programme, and plans for investing in green energy. Although the president successfully persuaded the cabinet to adopt the Mesopotamia Revitalisation Project as a policy framework, for it to receive funding and become operationalised, Iraq’s political leaders must be willing to invest funds in these long-term initiatives. While they are currently stymied by being unable to pass a budget, most Iraqi decision-makers nevertheless prefer to pursue short-term populist giveaways, such as public sector government employment opportunities.

The minister of finance, Ali Allawi, has also released an economic reform white paper that seeks to place the Iraqi economy on a more sustainable footing, freeing up public funds for investment in climate change responses. In this way, individual leaders can make an impact by raising awareness of the issue among the political elite.

Despite the gloomy outlook, the Mesopotamia Revitalisation Project and initiatives such as Allawi’s show that climate change is finally receiving some attention at the highest level of Iraqi politics. Whenever Iraq’s political establishment manages to agree a new government, it will be critical for it to prioritise the funding and implementation of ambitious initiatives to address the impact of climate change. Wider impacts from the climate crisis will ultimately mean Iraqi leaders cannot continue to ignore the problem.

Public attitudes

Although exact levels of awareness of climate change are difficult to ascertain, the Iraqi public are alert to its impacts. From nomadic herders struggling with low rainfall to fishers reliant on shrinking lakes, concern is growing. Swathes of the public have articulated a link between climate change and their day-to-day struggles; issues such as water scarcity frequently drive protests. The public also believe that successive governments and local authorities have mismanaged the environment and failed to respond to the climate crisis.

The salience of climate change is likely rising. In the immediate aftermath of the war on ISIS, issues such as corruption, education, the economy, and reconstruction ranked above the environment as top local concerns. But, as the conflict recedes into the past and the damage done by climate change becomes more evident, public focus on the environment has intensified. During the dust storms that covered Iraq in the first half of 2022, social media was awash with posts pointing to the changing climate as the cause. There is also a demographic dimension to this, with young Iraqis keenly aware of the topic; a United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) survey found 67 per cent of under-18s in Iraq believed there was a “climate emergency”.

Economy and decarbonisation

If public and elite opinion ever converge on a plan for stronger climate action, real progress in Iraq will require foreign direct investment in green energy. But unless and until the country’s political elite take the steps needed to transform Iraq into an attractive environment for investment (which they have repeatedly refused to do) the federal government (and local governments) will lack sufficient resources to invest in conserving water, halting and reversing desertification, and improving energy security through developing Iraq’s considerable renewable energy potential.

Economic reform could assist in this, and is in any case necessary. Over the past decade, oil revenues accounted for more than 99 per cent of Iraqi exports and 85 per cent of the government’s budget. Allawi has pointed out that if the world reaches net zero emissions by 2050, net revenues for oil-producing countries will collapse by 75 per cent. Significant opportunities are likely to arise in moving away from oil – which dominates the economy but represents only 1 per cent of total employment in the country. In contrast, a transition to green energy may offer more job opportunities.

Yet, the extremely undiversified nature of Iraq’s economy leaves it vulnerable to the global shift towards decarbonisation; the European Union’s European Green Deal, among other drivers of decarbonisation, could have serious geopolitical implications for economies dependent on hydrocarbons exports. Iraq is a signatory to the Paris Agreement to limit global emissions, although it has pledged to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by only a modest 1 per cent by 2035. An additional 13 per cent target is conditional on international support. Iraq’s finance minister has argued that this support will be vital to ensuring the transition of global decarbonisation has no negative impacts on Iraq or on the region’s security and stability. Iraqi officials have also warned developed countries and states not dependent on hydrocarbons not to push for too swift a transition.

Much remains to be done to secure investment to diversify the economy. Key to this will be to address Iraq’s deep governance shortcomings, including reducing corruption. Such steps would also help the country win investment for climate adaptation and mitigation measures, which would provide jobs and relieve social stress.

Iraq’s weak governance and capacity to respond to climate change

Governance

As noted, Iraq lacks a political culture able to respond to the challenges posed by climate change or to develop an economic transformation plan. But such problems have emerged at least in part because of Iraq’s existing weak governance and inability to turn policy into action in terms of services, regulation, or infrastructure.

The soaring price of oil means that Iraq could afford to invest in adapting to climate change and mitigating its effects. Yet, even if a future Iraqi government were to make serious budget allocations in this direction, it would also need to address several governance weaknesses. These prevent it from mitigating some of the aspects of climate change that could be within its control, were it to align its policy, its resources, and its governance and delivery structures.

Such weaknesses exist at the local and national level. For example, significant tensions have regularly arisen among governing institutions over water sharing, such as between the provinces of Maysan and Kut, and between the provinces of Muthanna, Qadisiya, and Dhi Qar. Officials from southern provinces such as Maysan and Muthanna complain that provinces to the north take more than their share of water, affecting them downstream. In March 2017, the governor of Muthanna, Faleh al-Ziyadi, sent bulldozers and security forces to remove water barriers in the al-Hamza district of Qadisiya, risking an armed clash. Former Dhi Qar governor, Yahya al-Nasiri, has remarked that “the governorates act unilaterally [on water], which portends a catastrophe”.

At the national level, the Ministry of Agriculture is responsible for irrigation, rather than the Ministry of Water Resources, leading to a lack of clarity in the setting and implementation of policies related to water conservation and the modernisation of irrigation techniques. This is important because Iraq currently uses extremely wasteful irrigation methods. It is vital that Iraq conserve water by modernising its irrigation systems, a task that the Ministry of Water Resources estimates would cost the country between $50-70 billion over the next 13 years. To do this, a more unified national government approach in cooperation with empowered provincial authorities would be able to help local farmers throughout the country quickly transition to low-tech methods that reduce water use.

Social impacts

Water scarcity in rural areas (exacerbated by Iraq’s poor water management) has multiple impacts. It can lead to desertification, whereby fertile land becomes arid. This threatens an astonishing 92 per cent of the country’s agricultural land and is set to drive massive domestic, and potentially international, migration flows in the future. Internal rural-to-urban migration is primarily driven by the collapse of rural employment opportunities, which occurs when there is insufficient water to farm agricultural land. The World Bank calculates that a 20 per cent decrease in Iraq’s water supply could depress demand for agricultural labour by 11.8 per cent and reduce the country’s GDP by $6.6 billion, or around 4 per cent.

This has an impact on food security: water scarcity and droughts are causing more frequent crop failures; in 2021, 37 per cent of farmers reported wheat crop failures and 30 per cent reported barley crop failures. Drought also has a severe impact on pastoral farmers, with crop failures pushing up the price of livestock feed and water scarcity leading to the proliferation of waterborne diseases that harm livestock. Small-scale farmers and nomadic communities are the least able to absorb the shocks to their incomes created by droughts and are therefore the worst affected.

These environmental difficulties raise social stress levels and put an already-weak state under pressure. They contribute to unrest in depopulating rural areas, raise demands on service provision in urban areas, and heighten local anger towards governing elites. Growth in the availability of day labourers who can no longer find work in agriculture is increasing competition for work in other sectors, such as construction in urban areas. Such competition, in turn, is causing tension between displaced persons and host communities in a number of provinces including Karbala, Salah al-Din, and Diyala.

In some areas, tensions have led to armed conflict, such as in parts of Dhi Qar and Maysan around the southern Shatt al-Arab, and where violence broke out when displaced people grazed their buffalo herds on land over which they hold no rights. Local conflicts driven by tensions between displaced people and host communities are likely to increase as migration flows escalate, as population growth continues unabated, and as Iraq’s governing authorities struggle to provide the basic services required to sustain their growing urban populations. Competition over limited urban housing is intensified by domestic migration flows, and is fostering the growth of slums in affected cities. Meanwhile, these climate migrants are often marginalised and impoverished, and tend to be concentrated in parts of the city that are poor, unsafe, and have the fewest services.

Such changes are leaving Iraq more vulnerable to the mercy of global trends and events: approximately half of the country’s food supply is imported, with the war in Ukraine contributing to high food prices. According to the World Food Programme, 2.4 million Iraqis are in acute need of food and livelihood assistance. Prices of some foodstuffs in Iraq have increased by 20 per cent. Baghdad has raised the price it pays Iraqi farmers and provided grants to some lower-income families to shield them from the potential effects. But this is not a sustainable solution. Azzam Alwash, a climate expert and adviser to the president of Iraq, suggested to the author that the government of Iraq should switch the subsidies it already provides to the agricultural sector away from purchasing produce at (highly elevated) fixed prices and redirect it to support that incentivises farmers to adapt their irrigation techniques.[2] This would doubtless be a politically challenging move on its own; but, if set within a new context whereby the government is taking stronger steps to conserve water in Iraq and taking the Iraqi population on this journey with it, new policy possibilities open up.

More broadly, right across the country Iraq’s governance failures lead to cycles of mass protest. These have continued as citizens decry the failure of the state to adequately respond to a range of challenges, many of which are exacerbated by the impacts of climate change.

For example, from October 2019 onwards what became known as the Tishreen protests were triggered by a range of grievances including the lack of employment opportunities for Iraqi youth –compounded by the loss of rural livelihoods due to water scarcity-driven decline of the agricultural sector. This challenge intensified when state and non-state actors responded to the protests with shocking violence, killing over 600 protesters and injuring over 20,000 people. This response severely damaged the credibility of the Iraqi government and led to the resignation of the prime minister, Adel Abdul Al-Mahdi, and the ushering in of a new caretaker government.

In this way, each cycle of protest and violence further erodes the legitimacy of the Iraqi government – and increases Iraqi citizens’ disillusionment with politics. This growing chasm between the political elite and Iraqi citizens was on clear display in the historically low voter turnout in the parliamentary election in October 2021.

Besides the Tishreen protests, which swept across central and southern Iraq, localised protests regularly spring up in response to the specific challenges caused by climate change. For example, in March 2022, a demonstration in the al-Salam district of Maysan province took place in protest at the scarcity and contamination of water in the al-Batira river, which was leading to typhoid, scabies, and other skin conditions among the local population. Frequent protests have continued to take place in Dhi Qar province, with protesters blocking main roads to express their anger about the lack of services, including inadequate provision of water. The Kurdistan region has witnessed demonstrations, which rarely receive press coverage, such as protests in Sulaymaniyah in June 2021 following the proliferation of waterborne diseases.

In addition, the state regularly fails to guarantee electricity supply for a variety of needs, including air conditioning in scorching summer temperatures of up to 50°C. Power outages in southern Iraq in 2021 drove residents of Amara in Maysan province to show their anger by setting fire to tyres in front of the Electricity Maintenance Department. These protests spread across several governorates and forced the electricity minister, Majid Hantoush, to resign.

Further civil unrest can be expected to plague the country as the population in dense urban areas continues to grow, temperatures rise, and state services fail. These challenges would be less acute were the government able, in the first instance, to implement adaptation measures that alleviate social stress; and secondly if the government were to chart a course towards turning Iraq from a straggler to a leader in embracing a new, decarbonised economy that creates green jobs and improves Iraq’s food security.

Security

The combined impact of climate change-induced deprivations in terms of water, food, jobs, and services – with the government weak or absent in many parts of the country – has made certain rural communities in Iraq vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups that offer access to precisely these things. For example, widespread droughts in the provinces of Anbar and Ninewa in 2006 and 2007 destroyed thousands of rural jobs and contributed to the successful efforts of al-Qaeda in Iraq to recruit disaffected young men to their cause.

Water scarcity also helped to drive the growth of ISIS. In its early iterations, ISIS responded to extreme weather events by offering support to disadvantaged rural communities. This included distributing food during a drought in 2010 and handing out cash following dust storms that destroyed aubergine fields near Kirkuk in 2012. Because of this, farmers were among the most prominent early supporters of ISIS. Water scarcity also played into ISIS’s sectarian narrative, with the group encouraging struggling, water-vulnerable communities in Sunni areas to believe they were being neglected by a supposedly Shia-dominated government. For example, in Salah al-Din province, ISIS’s recruitment drive was more successful in sub-districts, such as Tharthar, that were water-stressed than in ones where water was more accessible.

The government of Iraq has recognised the role that climate change is playing in driving recruitment to extremist organisations. In April 2021 the minister of defence, Juma Inad, said the climate crisis’s impact on displacement of people, destruction of agricultural land, and increase in unemployment, drives youths “towards crime and terrorism”, leaving those without economic opportunities and livelihood “an easy prey to Daesh [ISIS]”. But it has so far failed to take concrete action to prevent this continuing.

Climate-driven displacement is also affecting Iraqi provinces that were liberated from ISIS, such as Ninewa and Kirkuk, and is undermining recovery efforts in those areas. Already 1.2 million Iraqi civilians are internally displaced because of the conflict with ISIS, and the impact of climate change could mean they remain displaced or force them to move on again. As of December 2021, records show that 300 families (approximately 1,800 individuals) who had returned to Ninewa following displacement during the conflict with ISIS had been re-displaced by drought. Most of these families were from the rural southern areas of the province and had been unable to provide food for their livestock because of low rainfall.

The impact of climate change also drives recruitment to political armed groups, which have a destabilising impact on governance and undermine state control. In Basra, for example, recruitment to armed groups is partly an outcome of the degradation of the environment around the Shatt al-Arab, with the all too familiar impacts of unemployment, displacement, and the breakdown of rural life. Some of these armed groups engage in illicit activities, including drug smuggling, and in political violence. They undermine the capacity of the Iraqi government to manage local conflicts and deliver services.

Finally, competition over water in rural areas is contributing to outbreaks of armed conflict between tribal groups. Such water-related tribal disputes take place predominantly in Iraq’s rural south. Although there are multiple drivers of tribal conflict, disputes over access to water are among the most common reasons for the outbreak of violence. Prominent tribes have in some instances diverted water for their own farmland, creating tensions with tribes that have insufficient water to meet their own needs. Water-related incidents in northern Basra have reportedly led to tribal disputes lasting decades and resulted in the deaths and injuries of dozens of people, with local figures saying water scarcity causes around 10 per cent of all ongoing tribal disputes. And incidents of tribal violence are on the rise: their number doubled between 2019 and 2020, and then surged again in 2021. Over half of the incidents in 2021 took place in Iraq’s three most water-stressed provinces: Basra, Dhi Qar, and Maysan. In some cases, tribal conflicts are triggering population displacement. Between December 2021 and March 2022, in the district of al-Hai, Wasit province, 25 families were displaced due to tribal disagreements over access to water.

In most cases, the government has been unwilling or unable to intervene, and tribal groups sometimes use violence directly against government authorities over water issues. For example, in Mosul, there have been reports of villages arming themselves and preventing authorities from constructing wells for neighbouring villages over fears it would reduce their water supply. In December 2021, in protest at water shortages, tribesmen from the Shuweilat tribe near Gharraf oil field in Dhi Qar shot a rocket and fired a heavy machine gun at a police patrol near an irrigation canal in Rifai district. As tribal groups acquire heavy weaponry, they are increasingly posing a severe challenge to local police authorities.

Iraq’s regional positioning on climate matters

The region in which Iraq sits is known in hydrological terms as the Tigris-Euphrates basin. It is particularly vulnerable to water scarcity, and satellite imagery shows that groundwater in the basin is decreasing faster than in almost any other basin globally. The exact levels of decrease are difficult to ascertain due to climate variability, droughts, changing water levels, and construction on the waterways – but the trend is clear. Estimates suggest that water flow in the Euphrates and the Tigris could shrink by 30 per cent and 60 per cent respectively by the end of the century. Rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall will continue to intensify this for all countries in the basin, but as a downstream country Iraq is particularly vulnerable to changes implemented by upstream states. Those countries, particularly Turkey and Iran, maintain that Iraq receives its fair share of water but mismanages it. Meanwhile, the demand for water continues to grow in Iraq as its population increases.

Iraq’s water scarcity is exacerbated by activities in neighbouring states, including infrastructure development, dam building, and the diversion of tributaries in Turkey and Iran. The reduction of water flows from these countries further reduces access to water in Iraq and negatively affects Baghdad’s relationships with them. The deputy speaker of parliament, Hakim al-Zamili, recently threatened to boycott Turkish and Iranian goods and to sever economic relations with the two countries over reduced water flows. Although such drastic action is highly unlikely, the statement demonstrates the issue’s potential to serve as a rallying cry for populist politicians and complicate cross-border relationships.

Turkey

The sheer volume of water in Iraq that originates in Turkey makes it a particularly significant country for the issue of water sharing. Some 90 per cent of water flow in the Euphrates and 40 per cent of the flow in the Tigris comes from Turkey, while other tributaries that join the latter further downstream also originate in Turkey. Climate change has forced Turkey to conserve an ever-greater share of its water, which has led since the 1990s to Ankara implementing large-scale infrastructure projects on its waterways. This includes the controversial Anatolia Project in the south-east of the country, which has led to the construction of 22 dams on the Euphrates and Tigris.

Since the 1960s, Iraq and Turkey have conducted a series of dialogues on water sharing. However, none has managed to produce an agreement that satisfies Baghdad’s concerns about the supply of water from Turkey. A recently ratified memorandum of understanding between Iraq and Turkey that commits to healthy water flow into Iraq is emblematic of the challenge: it states that Ankara will allow fair water flow but fails to specify an exact level. Meanwhile, infrastructure building in Turkey proceeds at pace. In November 2021, just two days after Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, opened the huge Ilisu dam on the Tigris, Iraq’s Ministry of Water Resources warned that Ankara was already planning to build another new dam on the same river.

Tensions between Turkey and Iraq over water sharing reinforce and complicate other tensions between the two countries, particularly over the presence of the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) in northern Iraq. The group has been fighting an insurgency against the Turkish state for several decades, and Ankara perceives it as its biggest threat. To combat the group, Turkey has established numerous military bases in Iraq and regularly conducts anti-PKK operations inside Iraq, most recently Operation Claw-Lock. Turkey has conducted air strikes in Kurdistan and in the contested and vulnerable Ninewa province. Such operations both challenge Iraqi sovereignty and weaken Baghdad’s governance, taking up government, security, and political capacity and attention that could otherwise focus on issues such as climate change.

The issue of water aggravates Turkey’s conflict with the PKK. Pro-government media in Turkey explicitly cast new infrastructure such as the Ilisu dam as disruptive to the PKK. But in the long term, such projects are likely to intensify the displacement of Kurds within Turkey and increase support for the group there. Iraq has been in negotiations with Turkey to buy military equipment in return for increased water flows and the removal of Turkish troops from a base near Mosul. In this complex picture, the PKK conflict and its related issues will continue to be a point of leverage and contention in Turkey-Iraq water sharing discussions.

It is also worth noting that, historically, Turkey’s officials have been more than willing to use its position as an upstream country to pressure downstream countries into taking part in, or acquiescing to, anti-PKK operations. For example, in 1987 Turkey signed an agreement with Syria in which it explicitly conditioned releasing water on Damascus ending support for the PKK.

Iran

In the context of climate change, important aspects of the relationship between Iraq and Iran include water sharing, Iraqi reliance on affordable imports from Iran, and energy supply.

Iran is a vital but precarious source of water for the southern provinces of Iraq. The Karun and Karkheh rivers, which begin in western Iran, flow into the Shatt al-Arab river near Basra. But Iran has been increasingly diverting tributaries to meet its own domestic water needs. The minister of water resources, Mahdi Rashid al-Hamdani, has on multiple occasions warned that Iraq is planning to file an international lawsuit against Iran for cuts to the water supply, and to contest Iranian infrastructure building on rivers that flow into Iraq. He has also threatened to take Iran to the International Court of Justice or bring a case to human rights bodies such as the UN Human Rights Council. In December the minister claimed that Iraq was receiving just 10 per cent of the water it previously received from Iran, and said that the ministry “has completed all technical and legal procedures for the lawsuit” and prepared an eight-page report created by a panel of experts on violations by Iran.

However, Iraq appears to have taken no such international action, and any such process would be almost impossible for Baghdad to realistically pursue, given Iran’s extensive influence over Iraq’s political elite. In any case, Iranian officials reject the accusation that Tehran has limited water supply to its neighbour and some have told Iraq to focus on the reduction of water flows from Turkey. A senior adviser to the Iraqi government told this author that, although Hamdani has been vocal in his criticism of Iran, these are primarily political theatrics that emerge at times of domestic contention in Iraq.[3] The minister, who is politically close to the Sadrist Movement, has found it expedient to make such criticisms partly because of Iran’s declining reputation among the Iraqi public.

Food imports are also a significant factor in this relationship. Activists accuse Iran of deliberately starving Iraq of water to destroy the country’s agricultural sector and flood the Iraqi market with Iranian agricultural products. Such allegations have led to calls from civil society groups to boycott Iranian goods, while the Tishreen protests took aim (sometimes violently) at symbols of Iranian influence in Iraq, including embassies and consulates. In the context of severe international sanctions imposed on the Iranian economy, Iraq’s market has been a vital source of liquidity for Tehran. And poor harvests, crop failures, and declining yields for Iraqi producers have made it cheaper and more reliable for Iraqi markets to rely on foodstuffs exported by Iran, increasing Iraq’s dependence on its large neighbour.

Public anger has also boiled over during summer heatwaves when Iran has periodically halted the supply of power to Iraq over unpaid electricity bills. Protests at the lack of electricity in 2018 were accompanied by demonstrators setting fire to billboards of Iranian figures and to offices of Iranian-linked political parties in scenes that were repeated with great ferocity during the Tishreen protests.

Public anger is driven by the widespread view that powerful Iraqi political and armed groups are so closely tied to Iran that they are prioritising Iranian over Iraqi interests. As noted, Iraq is a country especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, and ill-equipped to address these. It is not out of the question that Iranian actors may redouble their efforts to use Iraqi political and armed groups to violently suppress local civil society opposition seeking redress for such impacts. If Iraq were to take more concerted steps towards addressing its climate vulnerabilities, it would remove one variable that complicates its wider relationship with Iran.

Kurdistan Regional Government

There are regularly political tensions between the Kurdistan Regional Government(KRG) and the federal government in Baghdad. The KRG has on numerous occasions sought to use its position as an upstream territory as a point of leverage in negotiations with Baghdad. For example, when budgetary disagreements arise with the federal government, Kurdish officials have on occasion suggested cutting water flows into Iraq, including in 2014 and 2020, even describing water as a “strong trump card”. During a dispute over livestock in 2016, Kurdish threats to withhold water elicited a furious response from Baghdad, with the federal government accusing the KRG of undermining human rights and violating the Iraqi constitution.

Water sharing has also become a flashpoint in disputed territories. For example, Arab farmers in Kirkuk have previously accused Kurdish authorities of deliberately reducing water to their farms in order to force them off their land. Intra-community tensions between Arabs, Turkmens, and Kurds over water have also been reported in Kirkuk in the past. The area has been under federal control since the 2017 Kurdish independence referendum and subsequent military confrontation. However, the land remains contested, and in any future escalation water could be a point of both leverage and contestation.

As with the relationship with Turkey, infrastructure pays a role, with the federal government expressing its anger at the KRG for pursuing the building of dams without its consent. In April 2022, the Ministry of Water Resources in Baghdad complained that the KRG had, without its knowledge, signed an agreement with a Chinese company to build four new dams. This took place in a context of heightened tensions between Erbil and Baghdad after a Federal Supreme Court decision had ruled that the KRG’s independent export of oil and gas was unconstitutional, which caused panic and fury in the regional government. As the federal government is now beginning to take action to implement the court’s decision, the KRG may be more likely to use its control of upstream water flows as a point of leverage in future negotiations.

Other regional relations

Iraq has participated in regional dialogues about potential coordinated action to reduce the impact of dust storms. Hamdani has announced a meeting is to be held in Baghdad with Iran and Turkey to discuss water, although no date has yet been set. Such regional initiatives are an important way to tackle the issue of climate change and build a stronger understanding of its shared impact and need for regional cooperation rather than competition. They are also taking place at a time when Iraq is playing a key role in bringing various countries in the region together for political and security dialogue. Baghdad could work to further expand such initiatives to encompass regional approaches to mitigating the impact of climate change.

Actions for Iraq

The Iraqi government must do more to manage competition over water between local government institutions. It could do this by creating a framework for coordination to ensure equitable distribution of water, perhaps based on an explicit and independently verified assessment of each area’s needs. This should also contain dispute resolution mechanisms to help reduce water-related tensions between different local authorities.

Iraq’s financial institutions – in particular, the ministry of finance, anti-corruption mechanisms, and affiliated entities – should increase efforts to improve Iraq’s investment environment. This will be crucial in helping the economy adjust to the transition away from fossil fuels. A particular focus should be to create a positive environment for investments in the green economy, including measures to understand and map out the potential of green energy in Iraq. This should proceed with the acknowledgment that corruption is deeply embedded in the country; improving the investment environment will be a long-term, slow-going, process.

Iraqi actors should approach any water dialogues or climate-related negotiations in good faith, including by reining in pronouncements and unnecessary legal threats against Iraq’s neighbours over water violations. Officials should refrain from using the issue to fire up their domestic political bases, and instead approach any concerns through formal diplomatic channels. This would both carry more political weight and prevent the politicisation of an issue that affects the whole of Iraq, not just certain sections of society.

Finally, local and national governments should run campaigns to prepare the public for the potential impact of climate change and increase awareness of the severity of Iraq’s position. Such campaigns should aim to build a consensus behind tackling the issue, thereby pushing more reluctant members of the political elite into action. Political parties and individuals associated with the protest movement, some of whom won parliamentary seats in October, should also put such issues at the front of their policy positions. This would help generate momentum as well as offer a solution to some of the social and public services crises that have disillusioned so much of the Iraqi public.

Actions for Europe

European states are committed to supporting stability in Iraq, and tackling the impact of climate change will be an important contribution to that goal. Europeans can offer specialist expertise to support Iraq to better respond to climate-related problems. But they should also emphasise the importance of giving domestic political priority to the issue, engaging the public directly on climate matters, strengthening internal governance, diversifying the economy, and pursuing regional dialogues more emphatically.

Political action

In the first instance, and on the political level, European states can encourage Iraqi parties to form a new government. They should look for opportunities within the processes relating to the formation of a new government to urge political leaders to adopt and fund a serious climate agenda. As a close partner to Iraq, the EU could take the lead in this regard, while also offering its expertise on devising policy.

The EU should formalise climate change as a core part of its engagement in Iraq. Although it is a leader on the issue, few of the EU’s strategy documents on Iraq explicitly refer to climate change, including the EU-Iraq Partnership and Cooperation Agreement and Council of the EU’s conclusions on Iraq. Individual countries such as Sweden officially acknowledge the political and social fallout of environmental change, but a comparable EU framework does not exist. Making climate change an explicit priority would also encourage member states to work further on the issue. Individual member states can also deploy their relevant expertise when helping Iraq; for example the Netherlands’ diplomacy with Iraq focuses on water management and food and agriculture.

The EU could also look to expand the role of the EU Advisory Mission in Iraq (EUAM), which is currently mandated to advise officials in the Office of the National Security Adviser and the Ministry of Interior on security reform. An expanded role for the EUAM could include establishing a specific unit tasked with supporting the Iraqi government to identify and address climate-related security risks.

In pushing for a political commitment from Iraqi actors, European governments should coordinate and work with other international actors with similar outlooks. For example, a recently announced joint UK-Canadian project designed to assist Baghdad to reach the targets it pledged in the Paris Agreement will provide momentum to adaption processes. Governments should explore creating other such initiatives.

Economy and reform

European states can continue to intensify their efforts to support the diversification of the Iraqi economy, including by encouraging European private investment and by transferring technical skills in the field of green energy. A range of European actors, including business associations, should continue to work with the Iraqi government to improve the country’s investment environment to attract foreign direct investment into the agricultural, green energy, and water management sectors. The EU could take the lead in this regard. It already holds workshops with Iraqi stakeholders under the UNDP’s Anti-Corruption and Arbitration Initiatives project, which aims to create a secure investment environment. It should expand such work with an added special focus on facilitating green investment.

European states can provide Iraqi political leaders and senior civil servants with technical support, training, and technology transfers, particularly to modernise irrigation techniques and to enhance the resilience of urban centres to rural migration. European states could begin joint investment initiatives to support the introduction of such new techniques. In this regard, the Iraqi government and European donors could collaborate with local civil society organisations to help farmers make this transition.

Local tensions and early warning systems

European states can help directly reduce local tensions generated by climate change by making specific targeted assistance available. For example, a recently announced EU project to improve water quality in Basra will not only have positive environmental consequences but may also reduce civil discontent in the city. Similarly, new European joint investment initiatives to help urban areas improve service delivery and prepare to absorb rural migrants could ease local tensions and prevent civil conflict.

European states can further support the Iraqi government by working with it to develop mechanisms to recognise and respond to early signals from local communities about specific conflict dynamics arising from the impact of climate change. This could work by combining satellite and meteorological data, such as on rainfall and predicted drought, with feedback loops that allow communities to report tensions – particularly over resources – thereby highlighting potential danger to the authorities. Similar mechanisms already exist in the Sahel, and could help prevent outbreaks of localised conflict. Similarly, European states could assist the Iraqi government to create and develop the capacity of local coordination mechanisms to respond to water conflict between provinces.

Local civil society organisations working with farmers on water management can collaborate with government media entities to raise awareness among the Iraqi public about the importance of conserving water and methods for doing so.

Importantly, European efforts to persuade the Iraqi government to prioritise water irrigation could have a real impact on the choices it makes – if Europeans frame this (and potentially other actions) in terms of helping Iraq protect its sovereignty. Notions of “restoring Iraq’s place in the region” are likely to find favour among both the political elite and the public.

Regional support

EU member states such as the Netherlands and Sweden are able to offer particular expertise on water management, and other European actors can support the Iraqi government to negotiate equitable water-sharing agreements with Turkey and Iran. Although this is likely to be a complex and long-term effort, they could do this by offering negotiation training to the Iraqi stakeholders mandated with discussing the topic with their Turkish and Iranian partners. They could also support negotiation processes that take place, including by providing mediation if they are asked to fill that role.

If Iraq takes genuine steps to conserve water, European states could help broker renewed dialogue between Turkey and Iraq over water sharing and could encourage both parties to divorce the issue of water from other nodes of conflict, such as Turkey’s cross-border raids on the PKK. European states should also support and encourage regional dialogues on a variety of climate-related initiatives, which would pay significant dividends in the medium term.

About the author

Nussaibah Younis is an expert on the politics, economy, and foreign relations of Iraq, and visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. She is a senior adviser at the European Institute of Peace, founder of the Iraq Leadership Fellows Program, and an associate at the University of Chicago’s Pearson Institute. She was formerly an International Security Program Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center. For ECFR, Younis previously authored “The gulf between them: What Arab Gulf countries can learn from Iran’s approach to Iraq”.

Acknowledgments

This paper was made possible by support for ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa programme from Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo.

[1] Author’s interview with President Barham Salih, June 2022.

[2] Author’s interview with Azzam Alwash, June 2022.

[3] Author’s interview with an adviser to the government of Iraq, September 2021.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.