Divided at the centre: Germany, Poland, and the troubles of the Trump era

Summary

- Berlin and Warsaw have very different ideas about how to respond to the challenge Trump’s presidency poses to Europe. While Germany emphasises the need to strengthen Europe’s resilience and unity, the Polish response has been to embrace the opportunities of the new political reality and enhance its bilateral partnership with the US.

- These differing approaches may aggravate the crisis in the Polish-German bilateral relationship and negatively affect the European Union’s defence integration and arms control policies.

- Warsaw should use NATO as the framework for discussions on strengthening the American military presence in Poland. Germany should be open to a strategic debate on the issue and no longer hide behind concerns about the NATO-Russia Founding Act (which Russia has abrogated).

- Instead of talking about “European sovereignty”, Poland and Germany should join other member states in clearly defining the vulnerabilities that the EU as a whole must address, including those resulting from US policy.

Introduction

For most Europeans, it is now obvious that the foreign policy of US President Donald Trump threatens the global liberal order. Trump’s hostility towards multilateral arrangements and his unilateral “America First” policy directly oppose the European Union’s interests and principles in many areas – from the Paris climate accord and the Iran nuclear deal to free-trade agreements and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. His foreign policy has also sparked debate in Europe on the EU’s defence capabilities and role in the world, including on whether “European sovereignty” can offset the United States’ apparent abandonment of its traditional role as guarantor of the liberal order.

Trump’s behaviour is also hitting Europe where it is most vulnerable – unity and cohesion between member states – at a delicate moment. As movements that attack the pro-EU mainstream are becoming increasingly popular in many European countries, Trump’s unilateralism and his emphasis on the nation state as the natural actor in international affairs are strengthening their nationalist narratives. Moreover, Trump’s attacks on Brussels align perfectly with the calls for emancipation from the EU’s supposed dictates from countries such as the United Kingdom, Poland, Hungary, and Greece. The US president’s power to deepen this divide in Europe – which is probably more severe than that created by the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq – should not be underestimated. Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in the relationship between Germany and Poland. At stake is much more than bilateral relations between two neighbouring countries. In many ways, the Polish-German relationship forms the principal bridge between east and west, connecting two still rather different parts of the EU. Indeed, as the relationship is key to the future of the European project in many respects, the current crisis between Poland and Germany is a problem for the whole bloc. And Trump’s behaviour threatens any attempt to ease tensions between them.

This paper analyses the Poland-Germany relationship in the context of their approaches to US foreign policy and, more broadly, their evolving perceptions of America as a global player and a partner of the EU. It pays particularly close attention to the ways in which Polish and German policies on the US have affected their EU defence ambitions and their attitudes towards multilateralism and Russia. Trump’s actions have brought about intense debates, new initiatives, and even important shifts in the foreign policies of Germany and Poland – which often have opposing priorities. While there remains a real possibility of a collapse in their relationship due to increasing mistrust, Berlin and Warsaw continue to have significant shared interests.

Crisis in the German-Polish partnership

Beginning in the mid-1990s, Germany was the most influential advocate of Polish accession to the EU and eastern enlargement more broadly. Poland’s interest in protecting its independence by joining the EU and NATO aligned with Germany’s desire to create a relationship with its eastern neighbours that was close as that with those to the west. Since 2004, when Poland and nine other eastern European states joined the EU, Polish-German relations have centred on Poland’s aim to create a “partnership for Europe” with Germany, as well as Berlin’s promise to treat Warsaw and Paris as equally important.[1]

Yet, today, the relationship is widely viewed as being weaker than at any time since 1989 – so weak that it hampers efforts to re-energise the European project. This could be seen at the November 2018 celebrations marking the centenary of Polish independence, during which Polish President Andrzej Duda visited Berlin for a two-day conference on Germany’s policy on Poland since 1918. Meant as a symbol of re-engagement and goodwill, the trip ended in disaster. Duda perceived German journalists’ questions about the Polish approach to the rule of law as provocative, while his audience booed his criticism of the EU. Similarly, Poland’s ambassador to Berlin irked his hosts by describing the last 100 years of German policy on Poland as a “single catastrophe”. Made in the presence of German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, this claim appeared to dismiss the three decades in which Berlin had pursued reconciliation with Warsaw and a constructive neighbourhood policy.

Taken together, these two events form a microcosm of the crisis in Polish-German cooperation that began in 2015, when the right-wing, populist Law and Justice Party (PiS) came to power in Poland. In many ways, the crisis stems from the differing trajectories the sides have embarked on in their respective European policies. In his January 2016 speech on Polish foreign policy priorities, then foreign minister Witold Waszczykowski named the UK as Poland’s key diplomatic partner in Europe. In the preceding 25 years, his predecessors had named Germany in this role.

While Warsaw’s rhetoric on Berlin has fluctuated during the last three years, mutual mistrust and major policy differences have continued to define their relationship, reflecting a deeper change in their perceptions of the EU. The PiS government has challenged the idea of closer EU cooperation, defended Polish national sovereignty against Brussels and Berlin, and rejected Germany’s role as the key power in the bloc. Disputes between the European Commission and the Polish government over the latter’s alleged violations of the rule of law, the Nord Stream 2 energy pipeline, and migration policy have overshadowed bilateral relations between Poland and Germany. As Warsaw criticised Berlin for its alleged dominance of the EU and demanded reparations for the second world war, German political elites complained about Poland’s refusal to cooperate on migration policy and its apparent lack of interest in improving the bilateral relationship.

Germany’s recent leadership in managing European crises has triggered a domestic debate about how to readjust German foreign and security policy to better fulfil this role. For instance, Germany has been instrumental in forging EU unity on Russia sanctions policy, contributed greatly to strengthened NATO deployments in eastern Europe, and, most recently, advanced the debate on European sovereignty in response to dramatic shifts in US foreign policy. As German political scientist Gunther Hellmann put it, “eine neuartige Erfahrung wird dabei sein, dass sich die Bundesrepublik nicht mehr automatisch auf die institutionellen Fixpunkte NATO und EU oder die Führungsleistungen zentraler Verbündeter wie die USA oder Frankreich verlassen kann, die der deutschen Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik in den vergangenen Jahrzehnten Orientierung und Entlastung lieferten” (it will be a new experience for Germany to be unable to automatically rely on institutions such as NATO or the EU and the leadership of major allies such as the US or France, which in past decades have provided orientation and relief to German foreign and security policy). While they have yet to determine the direction and scope of the rhetorical and political changes this requires, political elites in Berlin are increasingly aware of the implications of their country’s pivotal position in the EU.

Against this background, the 2018 edition of ECFR’s EU Coalition Explorer provides further evidence that the relationship between Poland and Germany has weakened in the last two years. Although the countries are in frequent contact with each other, most German respondents to the survey – comprising policymakers and policy analysts – view Poland and Germany as having few significant shared interests, and perceive Warsaw as relatively unresponsive to Berlin. Polish respondents still see Germany as being among their most important partners, albeit as less important than Hungary. However, German respondents view Poland as having disappointed their government during the last two years – and Polish respondents see Germany the same way. In the German view, Poland is as disappointing as Hungary and the UK.

This slump in the Berlin-Warsaw relationship reflects, and is one of the most important causes of, a wider European malaise. Arguably, one cannot solve the problems of uncertain leadership in the EU and the growing east-west divide within the bloc without addressing the Polish-German crisis. Both individually and as partners, Germany and Poland are key to the future of European integration.

Whether and how Germany could lead Europe – rather than act as the continent’s hegemon, as it is sometimes perceived – has become more pressing as the bloc stumbles from one crisis to the next. Berlin is likely to see itself as leading from the centre: acting as an honest broker for the various interests of EU member states rather than as an Ideengeber that provides clear guidance and seeks support for its own policy recommendations. It remains to be seen whether this form of leadership will suffice.

Nonetheless, Germany can only lead effectively if it has the trust, support, and cooperation of other member states – not least Poland, as its second-largest neighbour, a key economic partner, and the biggest country in central and eastern Europe. Leading from the centre can hardly work if it is seen as merely a cover for Franco-German bilateralism. This is why Berlin perceives the effort to bring Poland back into the fold as crucial to the legitimacy and efficiency of its ideal of European leadership.

As its stated goal is to maintain European unity, Germany cannot allow tensions between various parts of the bloc to create permanent political divisions. The country needs the cooperation of central and eastern Europe due to its close economic relationship with the region; its desire to find the right balance between protectionism and economic liberalism within the single market; and its aim to address security threats to Europe’s south and east.

While Germany is crucial to maintaining unity within the EU, it is Poland’s political course that will largely determine whether the bloc will become increasingly divided. With Germany intent on preserving the status quo in European integration, the Polish government seems determined to roll back the supranational concept of EU founder Jean Monnet in favour of an intergovernmental construction – “l’Europe des patries” (a Europe of nations), in the words of another French EU founder, Charles de Gaulle.

The fact that Polish and German policies are falling out of sync creates, therefore, a serious strategic challenge for not only Germany and Poland but the entire EU. Warsaw’s drift away from the European mainstream not only hampers Berlin’s aspirations to be an honest broker within a unified EU but also threatens the core Polish interest of maintaining a strong union. This is where the crisis of transatlantic relations – sparked by Trump’s behaviour – comes in. The Polish and German governments’ capacity to reconcile their policies on the US will have profound implications for the EU’s ability to pursue an effective independent foreign policy.

European sovereignty versus the US-Poland bilateral partnership

Berlin and Warsaw have very different ideas about how to respond to the challenge Trump’s presidency poses to Europe. The prevailing German reaction has been to stress the need to defend the multilateral order and strengthen Europe’s resilience – for Maas, the answer to “America First” was to be “Europe United”. In contrast, the Polish response has been to remain calm and embrace the opportunities of the new political reality. Thus, while Germany emphasises European unity, Poland is investing in its bilateral partnership with the US. In some ways, these differences originate in the countries’ diverging analyses of what Trump’s presidency means for Europe and the transatlantic relationship.

Interestingly, both the German and Polish narratives contain a large dose of fatalism. Germany’s new approach to America seems to be governed by what political scientist Thomas Kleine-Brockhoff calls “continuity theory”, or the “assumption that the changes in US foreign policy began well before Trump’s election – and will outlast his presidency well into the future”. If, having become overstretched in its global commitments, the US was always likely to dismantle the multilateral order and unilaterally pursue the American interest at any cost, Germany and the EU have to prepare for transatlantic tension (or even confrontation) that outlasts Trump’s radical presidency.

Poland’s fatalism about America has an entirely different character. It is anchored in the notion that US security guarantees are indispensable in an increasingly dangerous geopolitical environment. Due to the lack of viable alternatives, Poland has no choice but to bet on continuous American security engagement with central and eastern Europe. To ease their doubts, Polish politicians seek America’s assurances – as seen in their quest to attract additional deployments of US combat forces on Polish soil. Since the stakes are so high, investment in the relationship with the US seems the only approach that can pay off. And, if it fails, the outcome will not be more disastrous than that of any other strategy.

These differences may be unsurprising given Berlin’s and Warsaw’s diverging security perceptions, and the dissonance between traditional Polish Atlanticism and the long-standing anti-American sentiment sometimes found in Germany. A no less important factor is the roles the countries play in Trump’s vision of the world as a competition between great powers. He has singled out Germany as America’s main obstacle – even opponent – in Europe. Although his concerns about Germany’s large trade surplus and low defence expenditure are grounded in reality, Trump has criticised the country with an intensity that has chilled US-German relations for almost all his term. Within Trump’s narrative, a “very bad” Germany sharply contrasts with a reliable Poland, which meets NATO defence spending targets and is interested in an energy partnership with the US that would boost American liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports. Indeed, he has publicly courted the Polish authorities by visiting Warsaw in July 2017 and mentioning Poland as a key ally twice in his September 2018 speech before the UN General Assembly. Trump’s ideological similarities with the nationalist, populist Polish government and his differences with German Chancellor Angela Merkel – whom the international media has hailed as the last defender of the liberal order – are also crucial: while the Polish authorities saw Trump’s victory as continuing a political trend that began in Warsaw in 2015, the German political elite has publicly portrayed itself as fundamentally in conflict with the values and norms of the new America.

Merkel’s remark that “the times in which we can completely rely on others are somewhat over” – made in Trudering in May 2017 – is perhaps the most famous expression of the transatlantic crisis. The fact that she is widely seen as a committed Transatlantikerin (her support for the Iraq war in 2003 put her at odds with then chancellor Gerhard Schröder and even public opinion) lends particular significance to her words. In a subsequent television interview, the chancellor said that Germany’s “second loyalty” (after loyalty to its people) should be to the EU – an important shift from the days in which she gave the EU and transatlantic relations equal weight. Merkel has not specified what Germany’s new strategy should look like, but she has conveyed German leaders’ overwhelming distrust and frustration with the Trump administration’s foreign policy. In Germany, Trump has become a symbol of a historic rupture with the US, heralding the end of the transatlantic era and of America’s role as the key guarantor of the multilateral liberal order and the only reliable pillar of European security. Indeed, as Maas wrote in August 2018, “the US and Europe have been drifting apart for years. There is less of an overlap in the values and interests that shaped our relationship for two generations.”

Arguably, Trump’s behaviour has had a powerful impact on the Merkel government’s foreign policy, encouraging German leaders to echo French President Emmanuel Macron’s call for “European sovereignty”. Maas has set out to “reassess” Germany’s relationship with the US – and to create what he calls a “balanced partnership” in which Germany and Europe have an appropriate share of responsibility, and the EU can “form a counterweight when the US crosses red lines”. To this end, he has made substantive recommendations: establishing international payments and financial communications channels independent of the US; a European monetary fund; and a new alliance of multilateralists (comprising like-minded nations that oppose the US retreat from multilateral institutions). All in all, German leaders seek to address an “America First” foreign policy as a long-term challenge that requires Europe unity and resilience.

Meanwhile, their Polish counterparts reject any narrative that focuses on America’s new unpredictability and desire for retrenchment. Warsaw largely views relations with Washington through the lens of security policy. Although the Polish public and government were unsettled by the possibility of American-Russian rapprochement at the beginning of Trump’s presidency, this has not come to pass. The Polish authorities have felt vindicated in their belief that Trump’s presidency would not – as leaders in Berlin worried – have negative consequences for Poland and Europe more broadly. Warsaw did not take Trump’s remark that “NATO is obsolete” entirely seriously, as the US remained committed to strengthening the Alliance’s eastern flank. Indeed, despite the disconcerting rhetoric, American contributions to Europe’s security have materially increased under Trump. And this is, as Polish diplomats and experts underline, a matter of hard facts rather than perceptions.

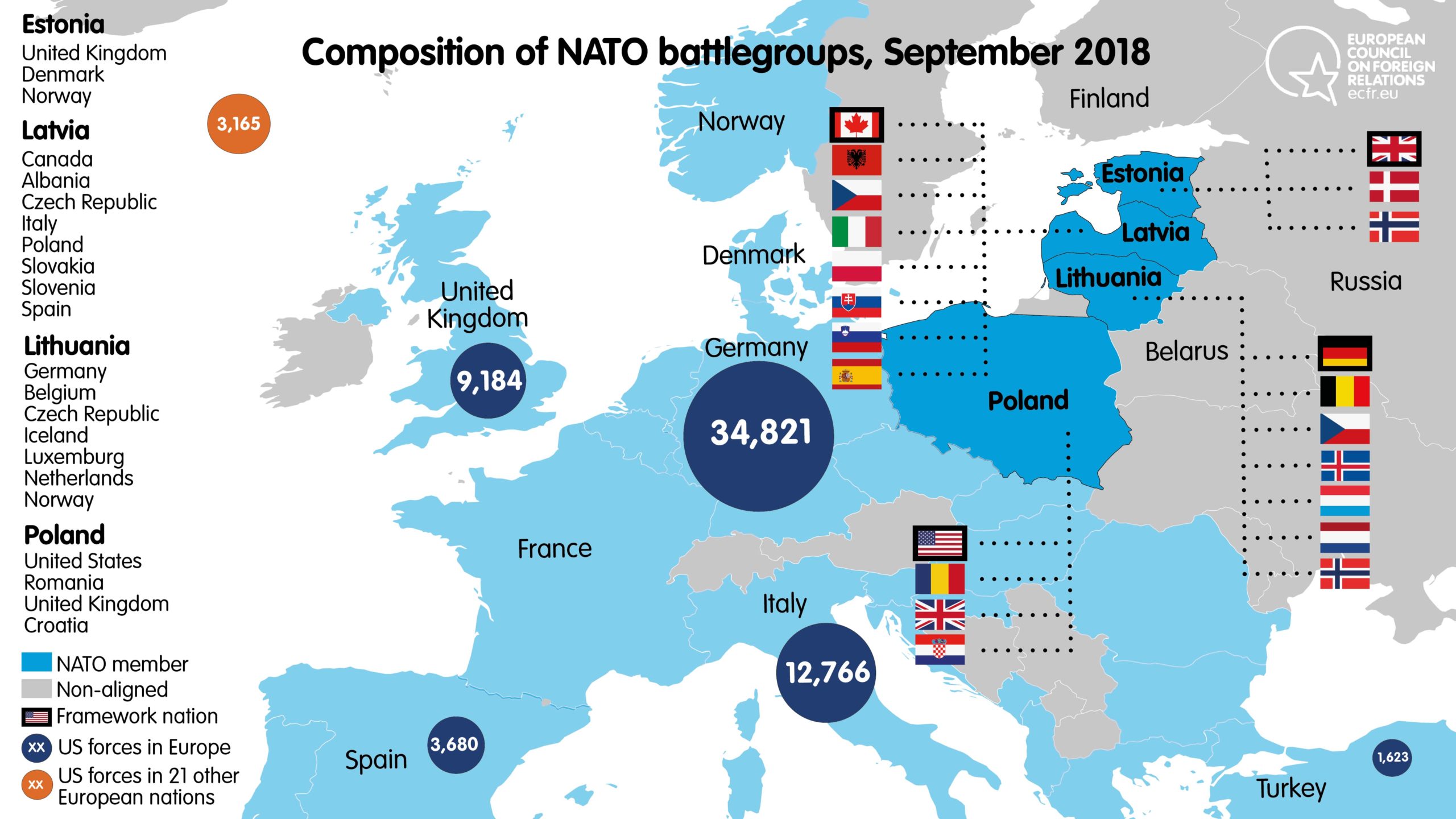

Not only has Washington fulfilled the commitments it made at the 2014 NATO Summit in Wales; Trump has also declared that the US will increase the budget of the European Deterrence Initiative from $4.8bn in 2018 to $6.5bn in 2019. America is deploying another three brigades to Europe on a rotational basis, while pre-positioning additional ammunition and training equipment there. From the Polish government’s perspective, there is no reason to complain about US retrenchment. The American military presence, seen as the cornerstone of Poland’s security, includes a military hub in Powidz, a rotational heavy brigade in Zagan, the Redzikowo base of the European Phased Adaptive Approach anti-missile shield (designed to protect the entire alliance), and occasional aerial and naval patrols or naval patrols in the Baltic Sea. Furthermore, the 2018 US National Defense Strategy defines Russia as a “strategic adversary”, in line with threat perceptions in Warsaw. In fact, the Polish government is much more enthusiastic about the direction of Washington’s current policy than that under Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, who attempted to “reset” American-Russian relations.

Germany and France criticise American unilateralism for threatening the West’s unity, but Poland has other concerns. In Warsaw, political elites’ fear that America will betray Polish or European interests is weaker than their concern about the consequences of loosening transatlantic bonds. In other words, pushing European sovereignty as the medicine for the transatlantic crisis is seen as more dangerous than the disease it intends to cure. This scepticism about the direction of the western European debate about Trump and transatlantic relations only enhances Poland’s eagerness to strengthen its bilateral relationship with the US and position itself as Washington’s best ally in Europe. As such, Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Bartosz Cichocki has predicted that “in a few years’ time … we can be in a completely different category of American allies” as “Poland is a kind of ‘substitute’ for the UK and Turkey in Europe.”

This ambition has become the driving force of Poland’s foreign policy. It was on display during Duda’s visit to Washington in September 2018, where he signed a declaration on a US-Polish strategic partnership. Instead of pushing for the US to defend multilateralism, Warsaw has tended to cultivate the bilateral relationship and accept – willingly or otherwise – Trump’s new rules of the game. Polish Foreign Minister Jacek Czaputowicz acknowledged in a speech at the Stefan Batory Foundation in October 2018 that Trump has fundamentally changed the way that international politics works – and that Poland needs to adapt to this new reality. During his recent visit to Washington, Duda asserted that he pursues a “Poland First” policy. And, in a speech to the UN General Assembly in New York, Duda did not echo his German counterpart’s call to defend multilateralism. Instead, he used the opportunity to criticise the current form of “multilateralism of usurpation and hierarchy”, contrasting this with “positive multilateralism of equal states and free nations” based upon the idea of “sovereign equality”. While Germany insists that the EU should establish strategic autonomy partly by taking foreign policy decisions through qualified majority voting, Warsaw perceives this as a threat to national sovereignty.

The foreign policy tension between Warsaw and Berlin is most evident (and most problematic for Europe) in Trump’s rejection of the multilateral Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on Iran’s nuclear programme. Germany has been at the forefront of EU efforts to establish a special purpose vehicle (SPV) designed to circumvent US sanctions on European companies that deal with Iran, while Polish diplomats regard any measures directed against the US as unacceptable. This may be at least partly because the SPV might also be used to circumvent potential US sanctions on European (particularly German) companies involved in the Nord Stream 2 energy pipeline project – which Poland has encouraged Washington to oppose. Therefore, on the JCPOA as other areas, the Trump administration’s foreign and security policy could have profound implications for EU cohesion.

EU defence autonomy

The American president’s criticism of low European (especially German) military expenditure and his ambiguous comments about NATO have lent new impetus to the debate on European defence. For France, the debate is about autonomy; for Germany, it is about responsibility. Meanwhile, Poland and several other countries have criticised the EU’s renewed interest in military cooperation for potentially undermining NATO. Arguably, it is inconceivable that Europeans would have engaged in so many political declarations and substantive projects – such as Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Intervention Initiative (E2I) – in their current form and scope without Trump’s interventions.

In this way, security and defence policy has become an unexpectedly promising avenue for European integration. European countries now broadly accept the idea that they should do more on defence. However, the speed and form of this “more” are no less contentious than they were before Trump entered the White House. In fact, Trump’s behaviour has exacerbated the differences between some EU member states – not least Poland and Germany (as well as Poland and France). In a nutshell, the more Germany and France engaged in discussions about a “European army” or “common defence” as a response to what they perceive as the new transatlantic reality, the more Poland has emphasised the primacy of NATO and sought a closer relationship with America.

Poland has long been concerned that the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) would weaken the transatlantic alliance by needlessly duplicating NATO structures and capabilities. One of the first decisions the PiS government made was to cancel its predecessor’s order of French Caracal helicopters, thereby damaging security cooperation with Paris and undermining Warsaw’s credibility within the EU. Poland only joined PESCO reluctantly and at the last minute (perhaps with the aim of watering down the project). And the country has traditionally preferred to work with US defence companies rather than their western European competitors – regardless of who occupied the White House.

Poland’s long-standing concerns about the CSDP have grown due to its European partners’ response to the apparent shift in US policy on Europe under Trump. France’s dominant role in the response has played a particularly significant part in this. Macron pushed for greater European sovereignty in defence by advocating for an ambitious version of PESCO and launching the contentious E2I.

Designed as an intergovernmental “coalition of the willing” outside the EU’s legal framework, the E2I came in response to France’s failure to found PESCO as an exclusive group of countries that had similar threat perceptions and were able to develop common defence capabilities. The version of PESCO the EU eventually adopted reflected Germany’s thinking more than that of France: while Paris was mainly interested in creating EU military capabilities and structures, Berlin focused on the political effects of the CSDP as a vehicle for EU integration. Berlin’s support for broad participation in PESCO – including countries as sceptical of the project as Poland – caused Paris to turn to other initiatives.

Thus, while France may not have been entirely successful in pushing its defence agenda, it has undoubtedly driven efforts to respond to Trump’s challenge to Europe. For Poland and other countries in eastern Europe, the fact that the UK played no role in these defence cooperation plans and discussions was also important. As a pillar of the transatlantic relationship, the UK has long been a respected security partner in the region. In line with Warsaw’s identification of London as a key ally, the sides finalised a bilateral security partnership agreement in December 2017. The UK’s decision to leave the EU likely helped spur the deal, as it will leave the bloc with one less strong advocate for ensuring NATO remains Europe’s primary security provider.

Meanwhile, Germany has limited its involvement in the debate on European defence cooperation due to the peculiarities of its approach to security policy. Supporting the establishment of a European army has long been part of the electoral platforms of both the Social Democrats and the Christian Democrats (as reflected in their current coalition agreement). However, this vision rarely guides policy planning. Mostly interested in the political dimension of the CSDP, Berlin has welcomed European defence cooperation as a form of integration that would strengthen the EU rather than as a tool to develop shared military capabilities.

Equally, Germany lacks a strategic culture with clearly defined security goals and an understanding of the instruments needed to achieve them (France, in contrast, has always had a clear idea about the threats it wanted an upgraded CSDP to address). And the poor condition of the German armed forces – which German politician Hans-Peter Bartels has described as of ‘limited use’ – undermines Berlin’s credibility as a security policy actor.

As a result of these factors, Germany has oscillated between passivity and control in the European defence cooperation debate. Although Merkel has used Macron’s language on defence issues – most strikingly, in repeating Macron’s call for a European army in November 2018 – Germany has always worked to prevent the establishment of an exclusive PESCO or any other EU defence project it perceives as too disconnected from the transatlantic relationship. Nonetheless, Berlin has had little active input in the policy debate – a fact that only strengthens Polish elites’ belief that the idea of ‘European defence’ is largely a French post-transatlanticist project.

Therefore, Poland joined two PESCO projects in 2017 and six more a year later with the explicit goal of strengthening the European contribution to NATO and preventing the creation of autonomous European capabilities. Warsaw’s main concern about PESCO has been that joint EU capability planning would undermine collective territorial defence, as western European countries would be more interested in developing military capabilities designed for crisis management and foreign intervention (particularly in north Africa) rather than those for responding to Russian aggression. This gap between eastern and western European countries’ threat perceptions is key to the differences in their approaches to, and expectations of, PESCO – as seen in Poland’s suggestion that the project should even include non-EU members. As Minister of Defence Mateusz Blaszczak stated: “I mean here the US in the first place, but also Norway and the UK after Brexit.”

Unsurprisingly, France did not invite Poland to join the E2I. In November 2018, Macron went a step further, arguing: “what I don’t want to see is European countries increasing the budget in defence in order to buy Americans’ and other arms or materials coming from your industry. I think if we increase our budget, it’s to have to build our autonomy and to become an actual sovereign power.” This definition of European sovereignty is anathema to Warsaw, especially at a time when it is negotiating a major deal to procure the US Patriot missile-defence system. Polish daily Rzeczpospolita responded to the French president with a sentiment many Polish leaders share: “Macron’s activities are the reason why the future of NATO and the security of central eastern Europe are becoming even more dependent on the US”.

Indeed, while French and German thinking about strategic autonomy is based on the assumption that the EU can no longer fully rely on the US, the shift in Poland’s security policy towards transatlanticist or even Polish-American solutions is increasingly apparent. Like Trump’s verbal attacks on Germany, disputes within NATO about defence spending and Europe’s responsibilities have made the Alliance seem vulnerable and prompted Warsaw to mediate its security relationship with Washington through bilateral channels.

The PiS government celebrated Trump’s July 2017 visit to Poland for the Three Seas Initiative (TSI) Summit – during which the president delivered what his adviser Steve Bannon called his “most important foreign policy speech” – as its main foreign policy success, despite the fact that it had no tangible results. Nonetheless, Duda used his September 2018 visit to Washington to invite the US to set up a permanent American military base in Poland, colloquially known as “Fort Trump”, and offered to contribute $2bn to the initiative. In line with this, the replacement of rotating US military deployments on Polish soil (as agreed at the 2016 NATO Summit in Wales) with a permanent one has become one of the main declared goals of Polish security policy.

Poland’s insistence on a permanent American presence stems from its interpretation of Russian strategic thinking. According to Polish experts, the Kremlin views rotational deployments as a limited commitment – in both scope and time. As such, a permanent presence serves as a more effective deterrent. Warsaw does not accept the argument often put forward by German politicians that deploying American or NATO forces at the Alliance’s eastern flank would violate the provisions of the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act. Yet, from Warsaw’s perspective, Russia has repeatedly voided the agreement by changing the security environment, not least with its invasion of Ukraine and militarisation of Kaliningrad.

However, it is political rather than legal issues that make Fort Trump divisive within the EU and NATO. A bilateral deal on a permanent American military deployment in Poland would erode the carefully constructed consensus between the country’s NATO allies. To be sure, the Polish government has stressed that Fort Trump would be based on an arrangement that did not require their consent: Czaputowicz told NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg in October 2018 that they would merely “be informed” about the talks with the US, arguing that a permanent deployment would strengthen the Alliance as a whole. Germany disagrees (as does France).

Aside from the fact that it could be militarily counterproductive, establishing a permanent American base on Polish soil outside the NATO framework would be politically costly for Poland. By betting on an unequal bilateral alliance and alienating Germany and France, Poland could quickly become a dependent client of America – under Trump or subsequent presidents. Warsaw can be useful to the Trump administration in reducing the EU’s cohesion, thereby preventing unified European opposition to Washington on issues such as the INF Treaty and the JCPOA. In this way, concessions the US might extract from Poland in talks on Fort Trump could affect how the EU approaches these areas.

Polish excitement about Fort Trump may well turn out to be premature even if, as expected, the US boosts its military deployments to Poland without establishing a permanent presence there. Trump seems reluctant to send more troops abroad without having a good cause for doing so – not least because of his campaign promises on this. He seems likely to portray Poland’s request as evidence of the success of his tough approach to NATO and European defence spending. The prospect of a permanent base may end up as a bargaining chip in NATO’s internal debates – or even in US-Russian discussions.

A new rearmament debate?

Trump’s announcement in October 2018 that the US would withdraw from the INF Treaty could set Poland and Germany on opposite sides of a crucial European security debate. Signed in 1987 by US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, the treaty prohibits America and Russia from developing and deploying land-based missiles with a range of 500-5,500km. As it bans the weapons the countries could use to fight a “limited” nuclear war in Europe, the agreement is widely perceived as a cornerstone of European security. Trump’s announcement, therefore, partially decoupled European and American security interests, with potentially catastrophic consequences. Freed from the limits of the INF Treaty, Moscow could openly deploy intermediate-range land-based missiles capable of hitting targets across Europe from within mainland Russia, prompting a US response and increasing the likelihood of a new nuclear arms race beyond the US and Russia.

The US government has publicly accused Russia of spurning the treaty, partly by testing a cruise missile that exceeds INF limits, since 2014. However, there has been only a muted reaction from European countries as many of them have no way of independently verifying American intelligence on the missile – the SSC-8, a successor of the SS-20, which became the focal point of nuclear competition between the Soviet Union and the West in the 1970s and the 1980s. While Warsaw has voiced its concerns about the issue, Berlin initially described the evidence on the tests from American intelligence as “not unambiguous”. The German government then went further, responding to a parliamentary question from Die Linke’s Kleine Anfrage with the claim that the development of the SSC-8 did violate the INF Treaty. The silence of European leaders such as Merkel and Macron on the issue and Russia’s broader military build-up has long disappointed Warsaw.

Trump’s announcement about the INF Treaty has met with criticism in Germany. But there is no German public debate on the threat Iskanders deployed to Kaliningrad or other Russian missiles could pose to German cities. This is partly because Berlin believes there is little chance that Moscow will launch an attack and partly because German political discourse on nuclear weapons is still heavily influenced by the Nachrüstungsdebatte (rearmament debate) that took place in West Germany in the 1980s. In that era, the West German government led by Chancellor Helmut Schmidt demanded that NATO respond to the deployment of the SS-20. With the US seemingly reluctant to react, Schmidt feared that the American nuclear guarantee to Europe would not hold without the deployment of a Western system that would deter the Soviets from using the new missile.

The Alliance’s double-track decision in 1979 – which combined an offer of talks to the Soviet Union with the deployment of US Pershing II missiles in Germany – led to the collapse of Schmidt’s coalition government two years later. (His party, the Social Democrats, refused to support the deployment after it provoked the largest demonstrations in West German history and generated widespread public hostility to the US). Ever since, support for nuclear and other forms of arms control and disarmament has been one of the key features of Germany’s security policy and political culture. Against this background, the German public misread the discussions between Reagan and Gorbachev in Reykjavik in 1986, which eventually led to the INF Treaty, as a triumph of reason over the madness of nuclear arms races. In fact, the deal was a return to the status quo ante in nuclear deterrence.

Thus, Maas responded to Trump’s declaration about the INF by claiming that Germany “would fight with all available diplomatic means to defend the treaty”. Former Social Democrat leaders published a joint letter in which they warned against a new arms race and called upon Europe and Germany to be the voice of “disarmament and common security”. “Russia and the United States accuse each other of violating the INF”, they wrote, envisaging Europe as a neutral intermediary between the powers. Meanwhile, the Greens reiterated their stance that the US should withdraw the 350 or so nuclear missiles it has stationed in Germany.

Poland’s foreign ministry was far more conciliatory, stating that it agreed with the American assessment that Russia had violated the INF Treaty and, as a consequence, understood Trump’s move. (Minister Czaputowicz added that US withdrawal from the INF would not threaten Poland’s security because no new American intermediate-range missile would be used against Poland.) However, it is not Berlin’s and Warsaw’s differing views of the US decision and Russia’s alleged treaty violations that threaten to become the main point of contention, either bilaterally or within NATO and the EU. The most divisive issue is likely to be the effect of US withdrawal from the INF Treaty on Europe’s security environment.

The American decision needs to be seen in its wider strategic context. China – whose tactical nuclear weapons threaten US allies in the Pacific while America’s hands are bound by INF Treaty restrictions – is likely to be the real target of Trump’s decision. Nonetheless, the US has for some time considered a change in its nuclear strategy to address Russia’s military build-up. Indeed, the country’s February 2018 Nuclear Posture Review advocates strengthening American nuclear tactical capabilities through the deployment of sea-based missiles (which the INF Treaty does not cover). Yet, even before Trump became president, the US had mulled responding to Russia’s INF violations with the development and deployment of new land-based intermediate-range missiles. Following his announcement about the INF Treaty, it seems that the US will choose the latter option to redress the nuclear imbalance in Europe.

This debate could deepen the mistrust and misunderstanding between Poland and Germany, preventing the EU and NATO from formulating a common response to the challenges of a future arms race. In fact, from Warsaw’s perspective, a new arms race has already started – with the West remaining passive as the threat from Russia grows. Poland is particularly concerned about Russia’s military build-up in Kaliningrad and what it sees as the “nuclearisation” of Russian military doctrine. Unlike Germany, Poland has no aversion to nuclear weapons and still sees itself as a second-tier NATO member because it does not host permanent deployments of American missiles or troops. Warsaw rejects German criticism of efforts to strengthen NATO in ways that could violate the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, not least because Germany hosts large numbers of US troops and equipment. For the Polish government, this allows Germany to feel safe in a manner that Poland cannot.

However, the gap between Polish and German threat perceptions is even more fundamental than this. Warsaw sees its principal goal of further strengthening the NATO and US military presence on its soil as the only logical response to the current military imbalance between NATO and Russia, and the lasting military imbalance between Poland and Russia. In contrast, Berlin believes that increasing the American military presence in Poland would threaten the country – by prompting further Russian escalation. Breaching the NATO-Russia Founding Act would, so the German argument goes, cause Moscow to retaliate by amassing even more troops in Kaliningrad and, possibly, Belarus. This would make Poland (and Europe) less secure.

The announced American withdrawal from the INF Treaty makes a collision between these differing philosophies more likely. Because they believe an arms race is already under way, some PiS leaders claim that Trump’s decision could even provide an opportunity to restore the strategic balance, with Poland playing a key role in this by hosting “rapid reaction forces on its territory in [Fort Trump] as well as missile forces to deter Russia”.

Europe’s energy security

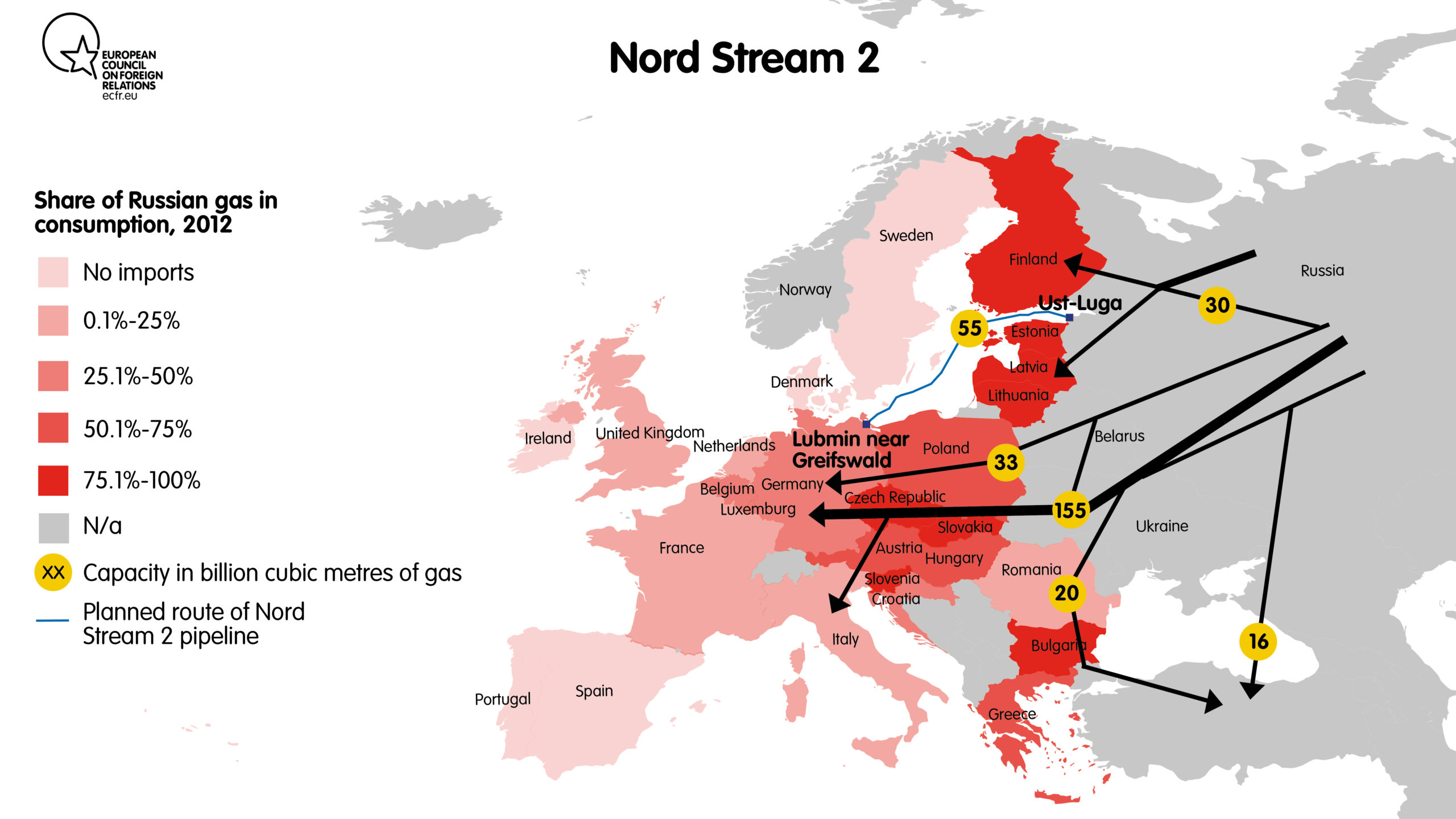

Trump’s behaviour has also driven a wedge between Poland and Germany on energy policy. To be sure, the countries’ conflicting views on cooperation with Russia and the importance of renewables have often put them at loggerheads with each other bilaterally and in the EU. This tension has considerably intensified in the last two years – and not only because of Trump. The key problem has been Nord Stream 2, which provoked heated arguments and legal disputes as it entered its final stage. However, Trump supercharged this controversy with an unprecedented (business-orientated) intervention on the topic, as well as his broader attitude towards Germany.

Energy has played an important role in the debate about the trade imbalance between the US and Europe. Trump’s strategy for reducing America’s trade deficit has been not only to impose tariffs and other restrictions on imports but also to increase American exports in lucrative sectors such as LNG. Thus, boosting European imports of American LNG has become a priority of his European policy – one that fits neatly with his depiction of Germany as America’s key adversary in Europe, not at least due to its huge trade surplus. Berlin supports Nord Stream 2, as it would make Germany the hub of central European gas supply lines. But the project would also cause EU member states, especially those in central and eastern Europe, to be more dependent on Russian gas imports.

Geopolitics aside, Trump believes that it is not in America’s economic interest for Europe to establish a closer energy partnership with Russia or for Germany to strengthen its economic position in central and eastern Europe. And Nord Stream 2, which is scheduled to become fully operational by the end of 2019, has remained a divisive issue within the EU. While some, especially Germany and Austria, openly support the project, others – mostly Poland and Baltic states, but also the European Commission – oppose it. Moreover, the development of LNG infrastructure (with terminals in Swinoujscie and Krk) is a priority of the TSI – a project involving countries on the Baltic, Adriatic, and Black seas that Germany has long viewed as an attempt to build an alliance within the EU, thereby weakening the bloc. Trump, who has never concealed his contempt for European integration, likely sees playing on these divisions as a means of enhancing US influence in Europe.

Warsaw doubtlessly hopes that American criticism of Nord Stream 2 will be decisive in the long dispute over the project. Supported by nine other EU member states, Poland has long opposed Nord Stream 2 for: weakening Ukraine, which currently exacts transit fees on Russian gas exports to Europe; working against the EU’s goal of diversifying its energy supplies away from Russia; and violating the Third Energy Package, which requires “unbundling”, or dividing energy extraction and distribution between different companies. However, these complaints have not had the desired result.

Berlin remains unimpressed with Warsaw’s arguments about the security risks of Nord Stream 2, though some influential voices in the German debate support this point of view. Most importantly, an attempt to use legal arguments to prevent the pipeline from being built, or at least render the project financially unsustainable, has failed too.

In September 2017, the EU Council’s legal service rejected (on Germany’s insistence, according to Der Spiegel) the European Commission’s request to allow it to negotiate a special arrangement with Russia on behalf of EU member states. The Commission also proposed an amendment to the Third Energy Package that would have required Nord Stream 2 to fully comply with the EU legislation, substantially increasing costs for the pipeline consortium. In March 2018, the EU Council’s legal service also rejected this initiative, dealing a powerful blow to Warsaw’s hopes. (Under proposed changes to the gas directive, all import pipelines would have to not be owned directly by gas suppliers, and would have to maintain non-discriminatory tariffs, transparent operations, and 10 percent capacity for third parties.) Having lost the battle within the EU, US interest in EU pipeline politics provides Warsaw with one last chance to derail the project.

It became clear that Warsaw might be able to count on US support in January 2018, when Rex Tillerson, then US secretary of state, visited Poland. Tillerson said that Nord Stream 2 is “undermining Europe’s overall energy stability and security” and that the US would “continue to take steps [to prevent it] as we can”. In an interview published shortly afterwards, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki urged the US administration to impose sanctions on the companies involved in the project. The issue of possible American punishment hit the headlines after Trump lashed out at Germany ahead of the NATO Summit in July 2018, calling Berlin “captive of Russia” and “totally controlled by Russia” while criticising the planned pipeline as “very inappropriate”. While Merkel emphasised that Berlin would make “autonomous decisions” on energy supply and German business representatives claimed that Trump’s threats “encroach on European energy policy”, Poland pinned its hopes on American determination to cancel Nord Stream 2. Indeed, during a visit to Warsaw in November 2018, US Energy Secretary Rick Perry confirmed that the US could still impose sanctions on companies involved in the project.

The dispute over potential US sanctions has driven a wedge between Poland and Germany, deepening mistrust between them more than any other issue. For Poland, sanctions provide its last chance to achieve a strategic goal; for Germany, the US threat of such measures is unacceptable interference in the EU’s internal affairs and German economic interests. Berlin also sees Warsaw’s drive for sanctions as completely unacceptable. As German diplomat Wolfgang Ischinger argued, Trump’s behaviour is pushing Germany “towards Russia and China”.

Poland’s strategic interest in energy cooperation with the US extends beyond Nord Stream 2. Warsaw rejected the new pipeline for not only geopolitical but also economic reasons – with American LNG imports playing an important role in its energy security calculations. Poland intends to allow its contract with Gazprom to expire in 2022, making it fully independent of Russian energy imports. The country will replace around 10 billion cubic metres of Russian gas per year with Norwegian gas imported through the planned Baltic Pipe, as well as LNG from various – ideally, American – companies. Swinoujscie’s LNG terminal has the capacity of 6bcm and is already operational. According to some Polish government sources, LNG imports and the Baltic Pipe could also help Poland become a gas hub in central and eastern Europe. The relatively high prices of LNG and Norwegian gas could prevent this from happening, as could a lack of interest in buying “Polish” gas in the region. However, long-term contracts with Gazprom linked to Nord Stream 2 would undoubtedly destroy any hope of achieving this goal.[2]

Therefore, Trump’s interest in promoting American LNG exports aligns with Polish strategic aims, creating common ground for an energy partnership. In November 2018, Polish state-owned energy giant PGNiG signed a 24-year LNG import contract with US firm Cheniere – under which, from 2023, Poland will buy 2bcm of LNG per year from the Sabine Pass and Corpus Christi terminals, in the Gulf of Mexico. The previous month, Poland signed a contract with US firm Venture Global LNG for 2bcm of LNG per year from 2022. The country is also negotiating two other contracts. While the exact price of the gas is not publicly known, PGNiG claims that it is 20-30 percent lower than that of Russian gas.

As part of the TSI, the energy partnership with America largely aligns with infrastructure projects between northern and southern European countries. Although Poland aims to become a hub for distributing gas across the region through the TSI, this would require further integration and an estimated €615bn in transportation infrastructure investment before 2025. Berlin worries that, in addition to weakening the unity of the EU, the TSI will undermine Germany’s political relationship with central and eastern Europe. This runs counter to Berlin’s strategic aim of remaining anchored in Europe’s east and west. While the Polish government has stressed the purely infrastructural character of the project, many PiS politicians and advisers have described the TSI as a plan B for Europe, should the EU collapse.

To strengthen its position as a regional leader and counterbalance Germany and France, Poland has encouraged the US to endorse the TSI and invest in the project. Trump’s July 2017 visit to Warsaw to attend the TSI Summit appeared to signal that the initiative has American support. So did his energy secretary’s visit to the TSI Summit in Bucharest in September 2018. However, the US has not announced any major investments in the TSI aside from those linked to LNG cooperation. As a result, its advocates hope that the EU will back projects in the framework of the TSI. Both European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and the Maas attended the Bucharest summit as observers. While Germany has shifted towards supporting the TSI (to avoid being left out), Poland would still prefer to work with the US on the project.

Renewing the German-Polish partnership

Trump’s behaviour has undoubtedly driven Berlin and Warsaw further apart on a range of issues. Weakening the consensus between European countries and undermining the EU appears to be the deliberate policy of the current US administration. Yet divisions between Berlin and Warsaw over transatlantic issues have at least as much to do with their long-held views of US policy, the EU, and NATO. Another principal obstacle is the pervasive mistrust between the German and Polish governments, which shapes their perceptions of each other. To put it bluntly, Germany sees the current Polish government as undermining the cohesion of Europe and ignoring the normative and legal obligations of EU membership. For Berlin, Warsaw seeks to roll back political integration while retaining all the benefits of membership, not least financial support. In contrast, Poland sees Germany as claiming a hegemonic role in Europe, using its control over institutions in Brussels to force its preferences on others. Given these irreconcilable positions, Polish-German disputes over how to respond to changes in transatlantic relations should come as no surprise.

Both sides should work to narrow the gap between them. German leaders have no interest in ending their partnership with Poland, as this would have far-reaching implications for Germany’s role in its eastern neighbourhood. Determined to contain centrifugal forces within the EU, Berlin aims to promote the benefits of shared sovereignty. Equally, Polish leaders have no interest in alienating their country’s most important economic partner. A cooperative Germany is Poland’s bridge to the west; a distant Germany could be a barricade. Both need each other, albeit for somewhat different reasons – Poland’s dependence on Germany is mostly economic, while Germany’s dependence on Poland is mostly political.

Nonetheless, current trends suggest that the bilateral relationship will deteriorate further. Avoiding this outcome will require a new strategy and significant political will. The latter is in short supply, especially in Poland. But Germany and Poland can reconcile at least some of their interests – to the benefit of both them and the wider EU. Initially, this effort should involve the following steps:

- Berlin and Warsaw should bring the discussion about strengthening Polish-American security relations into the NATO context. Ultimately, Europe’s security depends first and foremost on the unity of the Alliance rather than the number of troops it deploys. As Norwegian Foreign Minister Ine Marie Eriksen Søreide put it: “our military deterrent will never be stronger than our political unity and cohesion, and unless we have political unity, we will never be able to exercise our military capabilities.” Moreover, militarily, Poland would rely on NATO infrastructure to access the resources of a permanent American base on its territory. Nonetheless, Berlin should be open to a strategic – not legalistic – discussion about NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence in eastern Europe. The Kremlin abrogated the NATO-Russia Founding Act when it annexed Crimea, invaded eastern Ukraine, and, more recently, engaged in naval aggression in the Sea of Asov. Therefore, Germany should no longer hide behind concern about the act, as this undermines its credibility as a security partner of Poland and other central and eastern European countries. Simultaneously, any decision to move NATO beyond the conclusions of its Wales summit should be grounded in an analysis of current political and strategic realities, and should not refer to the NATO-Russia Founding Act.

- Germany and France should offer to engage in greater cooperation with Poland, particularly in areas of the defence sector where the country can make a significant contribution and gain substantial benefits. One such area is the main battle tank project. France and Germany currently run the project outside PESCO, but Poland could be genuinely interested – and, most importantly, able – to contribute to it. For Warsaw, limiting this project to the Franco-German tandem is evidence of western European countries’ unwillingness to grant Poland equal access to industrial projects and, as a consequence, of protectionism in the defence sector. (It is a good sign that Berlin and Warsaw discussed possible Polish participation in the project in November 2018.)

- Poland should voice an interest in joining the E2I. The biggest long-term security threat to the country is that its main European partners will come to perceive it as having abandoned their community of values and interests. Focused on rising competition with China and other powers, the US would be unable to compensate for this loss. And, as initiatives centred on intergovernmental cooperation rather than integration will become more common within the EU in the coming years, Poland should engage with the E2I to help maintain its influence on the development of the bloc. Most importantly, Warsaw needs to restore the balance between its transatlanticist and European defence orientations, and to maintain EU unity rather than to seek to benefit from the transatlantic divisions.

- Germany and Poland should rejuvenate their ailing attempts at military cooperation. The countries maintain the strongest conventional forces for territorial defence in central and eastern Europe. It is in both their interests to show through bilateral cooperation that they have taken on the responsibility of defending Europe. They could adopt the Dutch-German model of ground forces integration, setting an example for deeper cooperation between countries on the eastern flank of the EU and NATO. In the long term, any eastern European integration initiative for territorial defence would only be credible with the participation of Poland and Germany.

- While the clash between Russia and Ukraine in the Sea of Asov has boosted German opponents of Nord Stream 2, the project is likely to go ahead nonetheless. Germany bears most of the responsibility for dealing with potential fallout from Nord Stream 2 in Europe. The biggest risk of the project is that it will divide the EU gas market into western and eastern sectors, with Russia clearly dominating countries in the latter (aside from Poland). Berlin should take this risk seriously, working alongside Warsaw to limit the negative consequences of Nord Stream 2 at the EU level. German support for aspects of the TSI could form part of this effort.

- Instead of talking about “European sovereignty” or a “European army”, Poland and Germany should join other member states in clearly defining the vulnerabilities that the EU as a whole must address (including those resulting from US policy). Rhetoric matters. Because the disagreements between Poland and Germany largely stem from the mismatch in their perceptions of each other, they should make careful efforts to find common ground and align their public narratives. To this end, Warsaw and Berlin should begin a high-level reflection process on the future of the EU, perhaps with other partners – such as Sweden and Baltic states – to add a fresh perspective to proceedings.

Relations between Germany and Poland are too important to their broader interests – and to the cohesion of the EU – to be allowed to deteriorate further. Berlin and Warsaw both aim to shape the EU’s policies and institutions, even if they have profoundly different goals and strategies. Failure to address their differences and to overcome obstacles to cooperation would hamper both on the European stage – albeit in an asymmetric way, given the disparities between them in size, strength, and influence. As the fabric of EU cooperation is made up of strong bilateral relationships, neither Warsaw nor Berlin can afford to waste the potential of a once-productive partnership.

About the authors

Piotr Buras is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and the head of its Warsaw office, a journalist, author and expert in German and European politics. Previously, Buras was a columnist and Berlin correspondent for Gazeta Wyborcza, and has worked at the Center for International Relations in Warsaw, the German Studies at the University of Birmingham and at the University of Wroclaw. He was also visiting fellow at the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik in Berlin.

Josef Janning is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and co-head of its Berlin office. Janning was previously a Mercator Fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations, Director of Studies at the European Policy Centre in Brussels, Senior Director of the Bertelsmann Foundation, Deputy Director of the Center for Applied Policy Research, and has held teaching positions at the University of Mainz, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and at the Renmin University of Beijing.

Acknowledgements

This paper is the outcome of a joint European Council on Foreign Relations and Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung project. The foundation works to promote democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, and to support a thriving, dynamic civil society in Germany, Poland, and more than 100 other countries worldwide. In Poland, it focuses on strengthening European integration and fostering bilateral relations between Poland and Germany, as well as on transatlantic issues and fair, sustainable economic development.

Footnotes

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.