Clear and president danger: Democracy and the constitution in Tunisia

Summary

- The new constitution that Tunisia will soon put to a referendum is a fundamental departure from the democratic model the country established after 2011.

- The process of drafting the constitution excluded any significant political participation or public debate.

- The new constitution would create an unaccountable presidency and leave other branches of the state without any power.

- Tunisia’s president has failed to address the country’s serious economic problems.

- An agreement with the International Monetary Fund will only provide a short-term solution to these problems.

- European policymakers should make clear that they do not see the constitution as genuinely democratic, while continuing to support Tunisia economically.

Introduction

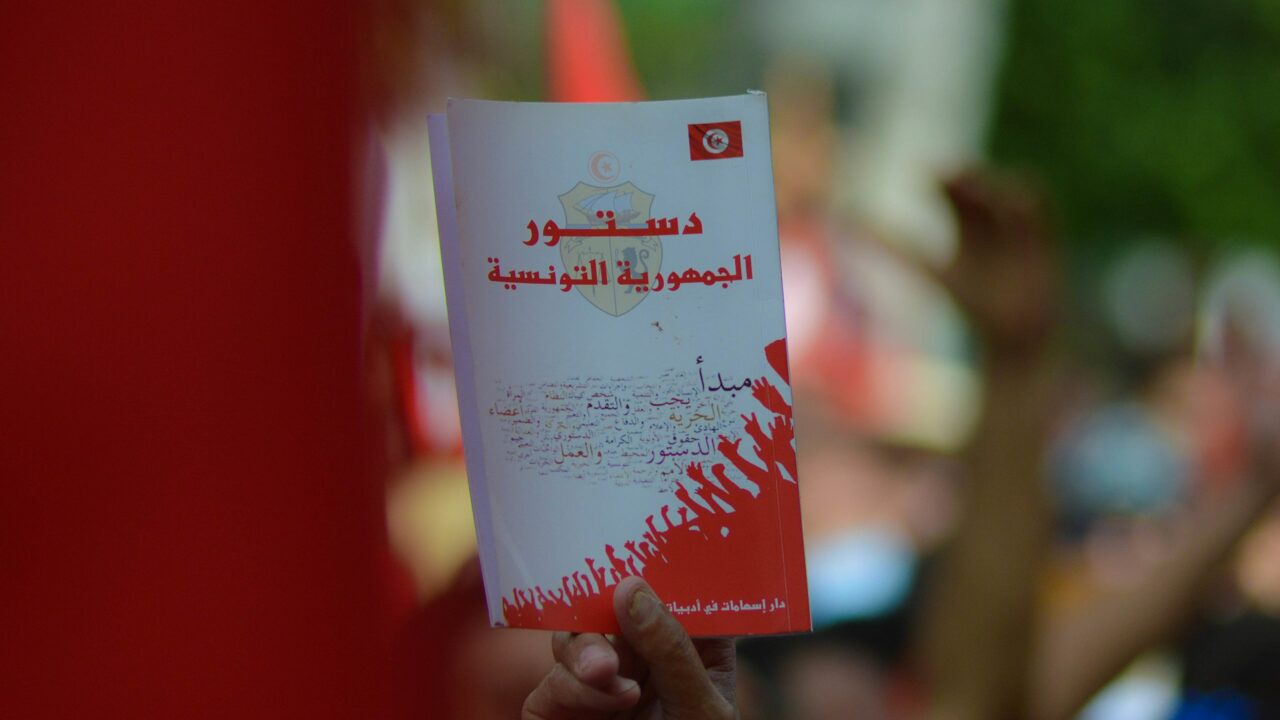

Tunisian President Kais Saied is on the threshold of establishing the “new republic” that he promised to build. On 25 July 2022, Tunisia will hold a referendum on the revised constitution that Saied put forward in late June. The constitution would create a system that effectively gives the president unchecked power. Saied personally rewrote the initial draft of the constitution submitted by an expert panel he had set up, leading the head of the panel to warn that this could pave the way for the creation of an open-ended dictatorship. Saied does not appear to have considered what will happen in the unlikely event that the referendum goes against him. He might attempt to impose the new constitution regardless of the outcome of the vote.

The new constitution is dramatically different from the current one, which was finalised in 2014 following the revolution three years earlier. The earlier document is the product of long consultations based on the democratic election of a constitutional assembly, an intense public debate, and a compromise between Tunisia’s main political groups. It embodies the idea of a democracy rooted in strong independent institutions. However, the new constitution is essentially the product of one man’s vision of centralised, unaccountable power. It has been drawn up outside any legal framework and with minimal discussion and consultation. There is little sign that the public is enthusiastic about Saied’s vision for Tunisia, but he has moved forward with it in the absence of any effective constraints on his actions.

Since Saied suspended parliament in July 2021 – a decision he justified as a response to the economic and covid-19 crises the country was facing – Tunisia has been operating outside normal political rules. Saied’s constitution would go further, by creating a new political settlement that would undermine the democratic achievements of the last decade. This pivotal moment poses a serious challenge to Tunisia’s partners in Europe and elsewhere that have provided significant support for its democratic transition. Adding to the complexity of the situation, the proposed revision of the constitution comes at a time when Tunisia’s economy is in a parlous condition, requiring international support to prevent a debt crisis and even a default.

This paper examines the flaws in the constitutional drafting process and in the resulting document, placing them in the context of Tunisia’s interlinked political and economic crises. It also suggests how Europe should respond. European policymakers are rightly reluctant to respond in ways that would impose greater hardship on the Tunisian people, such as by withholding economic assistance. However, if they accept Saied’s proposed constitution as democratically legitimate, they will be both betraying Tunisians who hope for an accountable political system and abandoning the investment that Europe has made in helping establish democracy in North Africa. By contrast, if they refuse to endorse the process and publicly state that the new constitution falls short of democratic principles, they will support the many Tunisians who have condemned it as a threat to their rights and freedoms, including legal scholars and members of political parties and civil society groups. It is time for democratic countries in Europe and beyond to take a tougher line on Saied’s accumulation of power.

A flawed constitutional process

The expert panel drew up the constitution against the background of Saied’s progressive dismantling of all checks on his power. Over the course of a few months, he set aside parts of the constitution that conflicted with his plans, gave himself the power to rule by decree in a broad range of policy areas, brought the Supreme Judicial Council under his control, and reshuffled the Independent High Authority for Elections (ISIE) to fill it with his hand-picked appointees. When MPs convened a virtual session to challenge his emergency measures, he dissolved parliament and threatened to launch investigations into those who had taken part.

The 2014 constitution requires that any constitutional amendments be endorsed by at least two-thirds of MPs and, if submitted to a referendum, receive an absolute majority of the votes cast. Yet Saied’s new constitution was drawn up with little outside input. The expert panel that hastily wrote the first draft was headed by law professor Sadok Belaid and drew on the results of an online public consultation earlier this year, an exercise that was widely ridiculed for its relative lack of participants. Saied did not provide political parties with any role in the process. And he gave only a few civil society groups a chance to discuss the draft; the most influential of these, the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), refused to participate in what its leaders described as a rubber-stamp exercise. The government published the final draft on 30 June – leaving no time for a substantive public debate on it before the referendum. One analyst rightly called the process a “national monologue”.

One constitutional expert described the political system that would be established by the draft constitution as “hyper-presidential”. The president would not only have sole responsibility for appointing the prime minister and the government but could also propose legislation, while parliament could only propose legislation for the government to consider and would need a two-thirds majority to vote down any bill. If parliament passed a no-confidence vote on two successive governments, the president could dissolve parliament and call new elections. The independent constitutional bodies regulating elections, the media, anti-corruption efforts, and other areas are central to the 2014 constitution, but are largely absent from the new draft – as are guarantees of the independence of those that remain.

The draft would allow for MPs to be recalled according to rules set by the president. And there would be no judicial independence or mechanism for replacing the president. In the words of Said Benarbia of the International Commission of Jurists, “the president is unaccountable, the other branches of State are reduced to mere functions, and the guarantees for the independence of the constitutional bodies … are absent.”

The new constitution includes no mention of Tunisia as a civil state or of civilian control of the military. Another striking feature of the document is that it says it would enter into force following the announcement of the results of the referendum without stipulating that a majority of voters need to approve it.

Remarkably, Belaid – who was once seen as a close associate of Saied – has strongly criticised the provisions that the president inserted into the final draft. Belaid argued that a clause allowing the president’s term in office to be extended in case of imminent danger to the state risked creating an “endless dictatorship”. He also argued that a provision stipulating that the state should work to achieve the objectives of “pure Islam” could open the way to a theocratic regime. Finally, Belaid warned that the addition of a second legislative chamber (representing Tunisia’s regions and districts) without a clear division of authority could lead to greater confusion. The rushed nature of Saied’s draft is reflected in the fact that, after just a week, he issued a revised version that corrected several mistakes and omissions.

The referendum will be overseen by the ISIE, which Saied reorganised to bring it under his control by issuing a decree-law in April 2022. In May, the Venice Commission acted on a request from the European External Action Service by publishing an urgent opinion on the new rules governing the ISIE and the wider framework of the referendum and elections. The commission criticised the decree-law as an unconstitutional violation of the principle of the separation of powers; it also condemned the uncertainty about whether the result of the referendum would be binding and the lack of a quorum for approval of the constitution. It called for the repeal of the decree-law, and for the referendum to be postponed until after the election of a new parliament. The commission said that the Tunisian government should, at a minimum, delay the referendum and clarify its rules; hold broad consultations on the text of the draft constitution; and reorganise the ISIE into its earlier form. Saied rejected the report as a “flagrant interference” in Tunisian sovereignty.

The president alone

Overall, the draft constitution appears to be largely the personal project of a single individual, bearing the hallmark of his long-standing concerns and idées fixes. Saied has progressively turned most members of the political class against his project. And there is little sign that the revision of the constitution is attracting much public interest. Several political and civil society groups endorsed Saied’s initial power grab. And much of the public appeared to support it due to widespread disenchantment with Tunisia’s sclerotic political system. But the president’s recent attempts to mobilise his supporters on political questions have flopped. As discussed, few Tunisians took part in the online consultation. All the indications are that most of them are far more concerned with the economy than with constitutional questions. Saied has done little to improve their financial situation.

The president is, in many ways, isolated. He relies on a small circle of advisers, including some radical leftists and Arab nationalists. His opaque, informal decision-making process has created a febrile political atmosphere fraught with rumours of rivalries between leaders such as Interior Minister Taoufik Charfeddine and Minister for Social Affairs Malek Zahi. The inflammatory rhetoric Saied directs at his political opponents has heightened this tension. Nevertheless, while Saied has a limited political base and rarely engages with the public, there is little to halt the advance of his political project.

The opposition’s strategy

In the months following Saied’s suspension of parliament, Tunisian political parties struggled to form a united front against him. However, as his determination to consolidate power and exclude his political rivals has become clear, the parties have put aside many of their disagreements. Most of them have signed up to the National Salvation Front created by veteran politician and activist Ahmed Nejib Chebbi, who has called for a fully inclusive national dialogue on political and economic questions to help Tunisia emerge from the crisis. Opposition politicians have put forward a road map involving a brief return of parliament, the nomination of a government of national unity, a dialogue process, and new elections. Almost all opposition parties have called for a boycott of the referendum because of the flaws in the process for drafting the new constitution and the final version.

Yet their arguments have not gained traction with the public. This is due to the opposition’s involvement in the discredited politics of the last decade, in which a series of coalition governments underpinned by a broad political consensus did little to address the country’s fundamental socio-economic problems. The religiously rooted Ennahda, which has long been Tunisia’s most organised political party, is one of the main targets of the public’s discontent. Its leader, Rachid Ghannouchi, has never indicated that he might step down. And there are few new faces in other opposition parties. Unless opposition leaders make an effort to acknowledge their failures and transfer control to a new generation, their parties will struggle to regain voters’ trust.

A partial exception to this is the Free Destourian Party, led by Abir Moussi. The party, which is now more popular than any of its rivals, centres on nostalgia for Tunisia’s early post-independence period of nationalism and secularisation under the presidency of Habib Bourguiba. Moussi, who refused to join the National Salvation Front because she did not want to work with Ennahda, is pursuing a parallel campaign of opposition to Saied’s centralisation of power.

The opposition sees public protests in Tunis and eventually the regions as the key to ending Saied’s project. However, neither the main bloc of opposition parties nor Moussi’s movement has been able to mobilise demonstrators in sufficient numbers to achieve this. Anti-Saied protests have recently drawn greater crowds than demonstrations in his favour, but disengagement from politics seems much more prevalent than support for the opposition’s alternative vision. And opinion polls continue to suggest that Saied is much more popular than any of his opponents.

The UGTT, which is the country’s most important political actor aside from the president, has been playing an adroit political game in which it protects its position and interests without alienating its politically diverse base. The UGTT was initially sympathetic to Saied’s suspension of parliament, but has distanced itself from him since then, criticising his failure to engage with other political groups in an inclusive way. However, UGTT insiders say the group is likely to remain focused on social and economic issues rather than an attempt to mobilise its followers on political or constitutional questions.[1] The secretary-general of the union, Noureddine Taboubi, has criticised several features of the new constitution but said that UGTT members are free to vote in the referendum as they wish.

A looming economic meltdown

Tunisia’s economy is in a disastrous condition. Its chronic problems have been exacerbated by the impact of Russia’s war on Ukraine, since Tunisia relies heavily on imported wheat and has been hit by increased prices for fertiliser, oil, and other commodities. Many analysts believe the Tunisian state could collapse financially in the coming months. Food shortages, price rises, and the late payment of salaries have added to what was already a severe cost-of-living crisis for Tunisians. Several ships carrying grain were forced to wait outside Tunisia’s ports while the authorities scrambled to find the cash to pay for the cargo before they docked.

Tunisia has been in talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) over a rescue package since last November, after earlier discussions were suspended following the dismissal of the government in July. The IMF has called for Tunisia to control its public sector wage bill, target subsidies more accurately, reform state-owned enterprises, make taxation fairer, and improve the business climate. It has also asked the country’s leadership to endorse these reforms in a public statement, to signal its commitment to carrying them out.

Saied long seemed reluctant to take this step, leaving it to ministers whose speeches carried little authority without his backing. He tended to use rhetoric on the economy that was at odds with the approach of his own government, reflecting a populist vision in which the country’s problems could all be solved by recouping money from corrupt businesses and members of the political elite.

However, during a visit to Tunis by the IMF’s Middle East director in late June, Saied announced that major economic reforms were necessary. The IMF then gave the green light for formal negotiations to begin, sending a team to the capital in early July.

The UGTT has taken a stand against the privatisation of state-owned enterprises and reforms to salary structures for public sector workers, while calling for a pay increase for its members who are employed by the state. The union claims that it recognises the need for economic reforms but that the government’s current plans place a disproportionate burden on public sector workers. It calls for complementary reforms that ensure the authorities can fully collect private sector tax revenues. The UGTT held a general strike in June to protest against the reforms and has threatened to take further action. The union’s actions may focus on economic matters, but they inevitably have a political dimension. Because the president has marginalised the UGTT along with other political and civil society groups, the union wants the president to consult it in formulating his economic plans.

Even if Tunisia reaches an agreement with the IMF, this would only be a temporary fix. The country needs to tackle deeply rooted economic problems such as huge inequalities between regions and the capture of many sectors by well-connected business elites. Moreover, the political uncertainty around Saied’s seizure of power has deterred investment in the country. Unless Saied changes course significantly, continuing economic hardship will likely cause many more Tunisians to turn against the president.

Indeed, opposition politicians appear to be betting that the government’s failure to manage the economy will help mobilise the population against it. Some anti-Saied campaigners believe that a combination of economic failure and the president’s political isolation will lead to a cascade of opposition activism – with social movements, the state administration, and political parties uniting to protest against his leadership. They argue that, in these circumstances, the army – which values order above all and would not want to take repressive action that might jeopardise its relationship with the United States – could force the president to resign. However, there is no guarantee that the opposition could control a breakdown of public order or that this process would result in a return to democratic politics.

Europe’s role

It will be difficult for Tunisia’s partners in Europe and beyond to navigate the country’s intertwined political and economic crises. The president’s prickly character and focus on sovereignty make him hard to influence. Nevertheless, this is a decisive moment: he is attempting to rewrite the constitution in a way that would reverse many of the democratic achievements of the post-revolutionary period. Of course, European states and other democratic countries should respect Tunisians’ right to choose their own political system – but that is not the issue in this case. Europeans should not appear to endorse either an exclusionary process that violates the existing constitution or the introduction of a new constitution that would make the president unaccountable.

Even if Saied imposes the new constitution on Tunisia, there is little chance that it will form the basis of a durable political settlement. The draft is shaped by his personal convictions – rather than any broader social consensus – and provides no solutions to the many problems the country is facing. Saied may still be relatively popular, but he appears to be isolated among the country’s political class thanks to his lack of an organised political following. And he seems to lack a plan and the commitment to tackle the issues that concern Tunisians most. Although Saied has sidelined many of the country’s major political actors, this reflects their weakness more than his strength. It is hard to imagine him dominating the Tunisian political sphere for years to come. While he appears to have the backing of Tunisia’s internal security forces, it is unclear how the army would react if he were to call for it to support his regime by repressing public unrest.

It is important for European officials to reject the idea that Saied’s vision for Tunisia will inevitably prevail. They should help the country deal with its immediate needs by supporting an IMF agreement with terms that take account of the difficulties Tunisians face. They should continue to provide direct economic assistance to Tunisia, helping it cope with shortages of food and fuel, as well as increases in their prices. And they should combine this assistance with a public statement that the new constitution should not be taken as a genuine expression of the wishes of the Tunisian people, making clear that they do not see it as compatible with democratic standards.

Even if Saied presses ahead with the new constitution, Europe and the US may still be able to discourage him from taking more repressive steps than he has done so far, such as greater persecution of political opponents and further restrictions on civil society. Saied has sometimes appeared to pull back from planned measures in the face of resistance and criticism. For example, he is rumoured to have put aside plans to abolish the Supreme Judicial Council outright. More importantly, a tougher European line on Saied would strengthen the hand of Tunisians who oppose his “new republic”, perhaps allowing them to gain political strength if his popularity wanes. Europeans should also try to deepen their exchanges with other parts of the Tunisian state, particularly the military, so that they are well-positioned to discourage repressive actions if the political situation in Tunisia deteriorates.

Europeans should also stress that the best way to improve Tunisia’s economic prospects would be to create a more stable and inclusive political system that encourages investment and provides the basis for a new economic policy. By showing concern for the hardships faced by the Tunisian people while denying the legitimacy of Saied’s new political settlement, Europeans can help Tunisia return to democratic standards and provide greater opportunities for its people.

About the author

Anthony Dworkin is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He leads the organisation’s work in the areas of human rights, democracy, and international order. Among other subjects, Dworkin has conducted research and written on the European Union’s support for multilateralism, political transition in North Africa, and European and US frameworks for counter-terrorism.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Julien Barnes-Dacey, Edin Dedovic, and – above all – Tarek Megerisi for continuing conversations about Tunisia, as well as for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. He would also like to thank Chris Raggett for his editing, which greatly improved the final product.

This paper was made possible by support for ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa programme from Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo.

[1] Author’s conversation with a UGTT adviser, Tunis, 11 May 2022.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.