Can Europe save the world order?

Summary

- The liberal rules-based order is under threat from both established opponents and former supporters. Europe has a vital interest in the preservation of a rules-based system, but it needs to rethink the elements of that order for a new global environment.

- The European Union can best support a rules-based order by ensuring its continuity at home; supporting liberal values abroad through the use of European economic power and alliances with like-minded states; and adjusting its strategy to protect the order’s core elements in an era in which illiberal states have growing power.

- A sustainable vision of international order would acknowledge the value of sovereignty at the national and European levels, while offsetting this with a commitment to developing new global norms where necessary and to enhancing the role of non-state actors. This approach would help tie multilateralism to the defence of Europe’s interests and values.

- The EU should put the defence of a redesigned rules-based order at the centre of its global strategy, and back it up by strengthening Europe’s financial independence and security capacity.

- The EU should also prioritise efforts to compensate for the global diplomacy deficit that US President Donald Trump’s policies have created.

Introduction

The world is becoming a scarier place. Trade wars loom, great-power competition is returning, proxy conflict is spreading, and President Donald Trump has withdrawn the United States from the Iran nuclear deal and the Paris agreement on climate change. Rules and alliances that once promoted international cooperation and stability seem to be losing their hold. In their place, there is a resurgence of international relations based on assertive nationalism, winner-takes-all competition, and disdain for the rule of law. Hopes that international politics would encourage the spread of democracy and human rights have faltered, while authoritarianism and illiberalism are in the ascendant. These changes have led many people to argue that the liberal international order developed after the second world war is breaking down.

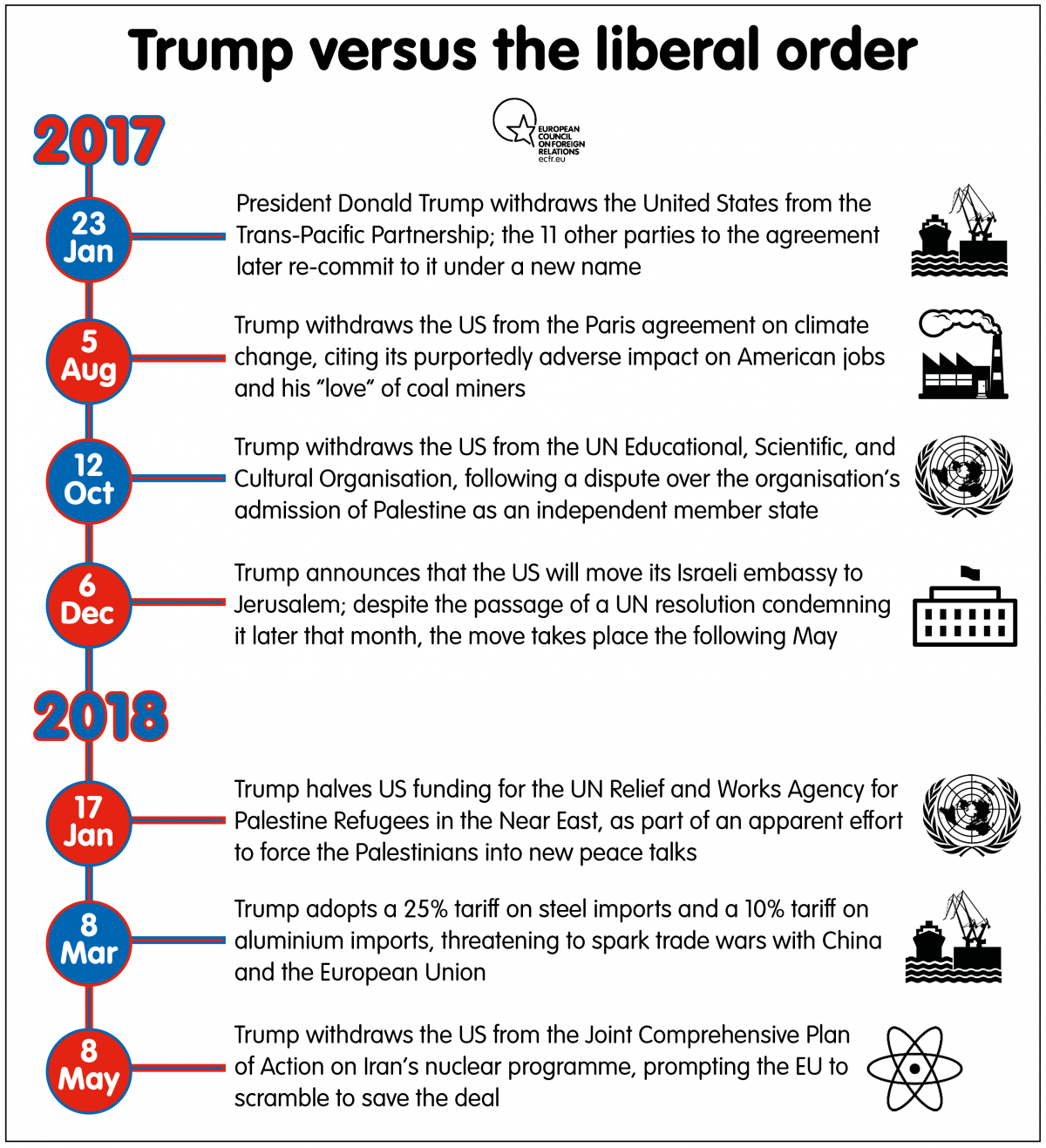

The rules-based order is under threat both from inside and outside. For most of the period since 1945, it was a joint project of the US and its European allies. But now Europe must respond to a radical shift in which the US – under Trump – has become a significant threat to the system. Trump’s policies and disregard for European views and interests have created a crisis that compounds longer-term strains on the international order. In response, the European Union urgently needs to design and implement a strategy for preserving the core elements of a rules-based order. This policy brief attempts to work out a vision of international order that could guide the EU, and to suggest how the EU could put this vision into practice.

The EU is heavily invested in the idea of a rules-based international order. The Union exemplifies the belief that states are most able to prosper through cooperation, openness, and a rule of law that incorporates a commitment to democracy and human rights. The EU’s international standing is linked to the credibility of the principles it embodies. More practically, European countries want an international order that protects them from external threats and allows them to promote their economic interests through worldwide trade and investment. European public policy is committed to the principle that multilateralism is the best way to create global public goods. Given these positions, the EU has good reason to be concerned about the condition of the liberal order, and to develop policies that aim to restore or preserve the order’s most important elements.

Yet this goal cannot be achieved merely by trying to roll back attacks on the order to recreate the international system as it existed in the past. The liberal order was never settled or perfect. It was an evolving, multilayered framework of norms, institutions, and practices that had internal tensions and weak points. Although it offered many benefits to its participants, the order was less consistent and inclusive than its proponents liked to think, and it was based on a distribution of global power that no longer exists. The task for the EU is not to look back but to shape a renewed vision of international order that is suited to today’s world, and to European interests and influence as they are now.

The liberal order’s evolution and challenges

The effort to develop a European vision for an adapted rules-based order requires an understanding of the international system’s evolution since the second world war. In the aftermath of the conflict, its victors set up a system of collective security focused on the United Nations and based on the principles of the prohibition of aggression and the peaceful settlement of disputes. As the cold war began, the US took the lead in establishing an alliance system that aimed to shore up democratic capitalism among its European allies by containing the advance of communism, liberalising trade with US allies, and promoting economic stability through international institutions.[1] This system could be described as “liberal order 1.0”. Although American leaders often presented themselves as defending the free world, some countries that the US supported – especially beyond the “core” of western Europe, Japan, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand – were more obviously capitalist and anti-communist than democratic. This order largely stopped at the borders of states and was less concerned about how they exercised sovereignty internally.

After the end of the cold war in 1989, the system evolved. The US promoted the development of a new settlement during the 1990s and early 2000s, creating what can be described as “liberal order 2.0”. The guiding idea was that the principled order established in the West after the second world war would be progressively rolled out to states not originally included. At the same time, in large part under European impetus, there was a deepening of the order to take account of the rights of individuals as well as states, and a partial embrace of a more constrained idea of sovereignty.

This second phase of liberal international order was not only a system of rules and institutions, but also a bet. It involved an expanded system of trade rules based on the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and mechanisms for enhancing economic coordination through international financial institutions and the G8. There were also gestures towards a greater commitment to human rights through institutions such as the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the norm of the responsibility to protect civilians from large-scale violence. The bet was that countries of the former Soviet Union and emerging powers such as China would converge on a basic minimum of liberal norms, and that global security cooperation through the UN could focus on new goals such as averting mass atrocities or suppressing international terrorism.

The problem now is that, while the goal of knitting the world together economically has been achieved, the bet on the consequences of this integration has not paid off. Non-Western powers have gained in wealth and global influence; however, there has been a decline in liberal democracy. At the same time, the supposed defenders of liberal order implemented its principles in ways that were sometimes self-interested or inconsistent, forfeiting the support of even emerging democracies while failing to convince their own populations of the benefits of internationalism.[2] The liberal international order turned out to be a work in progress that was capable of regression. More precisely, the aspirational goals embodied in the ideal of liberal international order are being challenged on three axes:

- Externally, many countries that were supposed to join the system are instead using their influence to pursue an old vision of great power politics in new ways; these states include China, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey.[3] As the distribution of power shifts, even emerging democracies look at the world through a post-colonial mindset rather than a post-cold war one – and they are unwilling to endorse an order that they see as linked to the dominance of the US and the West more broadly. For these powers, the liberal international order looks like “the world imperialism made”, in the words of the writer Pankaj Mishra.[4]

- Internally, the bargain that supported liberal foreign policies has come apart. Many citizens in the West now see openness and international engagement as working against their interests – as reflected in declining support for liberal internationalism in European countries. This public disenchantment lies behind the United States’ willingness to maintain its traditional role as the military and economic anchor of the system – as shown in Trump’s dramatic policy reversals.

- Transnationally, new challenges and forms of disorder have emerged that current structures fail to address, necessitating the development of new norms. Changes in the nature of conflict threaten to loosen the international rule of law; there are no adequate regimes for dealing with migration and refugees; and the regulation of cyberspace has failed to keep pace with its impact on people’s lives.

One interpretation of these developments is that the guardians of world order over-reached in the years after 1989. The rise of sovereigntist powers such as Russia and China, and liberal countries’ actions that undermined the legitimacy of the system, halted the utopian project of building liberal order 2.0. Partly due to the calamity of the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, the onset of the financial crisis in 2007-2008, and the subsequent travails of the euro, support for liberal order 2.0 will collapse. In its place there will be a return to a “thinner” international order – closer to liberal order 1.0 – that strips out any orientation towards human rights and democracy, focusing more on non-intervention and minimal rules of coexistence between great powers with different political visions. In this account, Trump does not represent a major break with past US administrations. Very few of them believed that the US should be subject to binding rules – they were just keener to impose them on other countries.

But there is a darker reading of our situation. In this view, we will face a rollback of even liberal order 1.0, driven not just by revisionist external powers but also by a political counter-revolution within the West. A new kind of globalisation – “world order 0.5” – will combine the technologies of the future with the enmities of the past. Military interventions will continue, but not in the humanitarian form that saw Western powers curtail genocide in Kosovo and Sierra Leone. The development of technology will spur a series of connectivity wars as states weaponise trade, the internet, and even migration.[5] In this world, multilateral institutions and regimes will become battlegrounds rather than brakes on conflict. Domestic politics that increasingly revolves around identity politics, distrust of institutions, and nationalism will foster greater international conflict.

The task for Europe is to find an alternative to these two regressive scenarios, one that accounts for both the rising influence of illiberal powers and the extent of global connectivity, and that European citizens can endorse. This will mean finding principles of order that can be effective in a multipolar world while working to advance progressive solutions to global problems as far as possible and craft a new social and economic compact within Europe’s borders. Pursuing this vision will require Europe to differentiate between the separate components of international order, matching priorities to capacities in different areas. It will also mean developing a specifically European strategy on international order.

Much discussion of the fate of liberal international order has come from analysts in the US and has adopted a US perspective. It tends to focus on promoting internationalist stances within the US policy debate.[6] But, while Europe and the US were closely aligned on questions of global order during the cold war, their interests today are more divergent. Europe has greater exposure to the effects of conflicts to its east and south, different economic concerns and regulatory standards, and a political culture that is much more accepting of multilateralism and international judicial oversight. The EU may be better placed than the US to distinguish between the preservation of a rules-based system and the maintenance of the US military and economic hegemony that has supported the liberal order up until now.[7] And Europe must adjust to the shifts in US policy that Trump has made – including his rejection of the Iran nuclear deal, or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which the EU saw as one of its main diplomatic successes of recent years.

The effort to renew the foundations of international order should also incorporate a clear vision of its underlying purpose. The idea that internationalism has benefited some groups or countries unequally, and that interconnection is a source of more threats than opportunities, lies behind the loss of support for multilateralism. In this sense, Europe must construct a renewed order on the basis of the needs and concerns that it addresses. In the way that French president Emmanuel Macron has called for a “Europe that protects”, the EU should seek to promote a “multilateralism that protects”, showing more clearly how the elements of international order that it prioritises work to the benefit of European citizens’ security and prosperity.

Europe should adopt a three-dimensional strategy on the future of international order:

- The EU must invest in defending liberal order 2.0 within the European sphere. This involves an attempt to strengthen the EU’s defences and resilience across several policy areas, as well as an effort to strike a new bargain between losers and winners within the EU.

- Beyond Europe, the EU should explore ways to develop an adapted version of a principled, rules-based order. Because the EU cannot (and would not want to) close itself off from the world, it should work to, as far as possible, establish the kind of order it sees as the best foundation for long-term stability and development in Europe and elsewhere. To do this, it will have to identify a wide range of potential partners and be prepared to rethink some of the supposed premises of liberal order 2.0.

- On a global level, there are areas in which the EU will need to prioritise a minimal threshold of rules-based order over any more ambitious attempt to promote liberal goals. Because even a renewed coalition of like-minded states cannot achieve its objectives in the face of more assertive and powerful illiberal states, this may involve compromising on European ideals in some cases and pulling back to a more sovereigntist agenda.

Given that the international order is not monolithic, we can identify priorities for Europe by breaking down the challenges it faces into four thematic areas. Two of them – security and trade – involve central features of the existing order that are increasingly under strain. In the other two – the global challenges of migration and climate change, and cyberspace – the existing order is underdeveloped and Europe needs to work with others to help build new regimes.

War, crisis management, and human rights

It is often said that recent years have seen the return of geopolitics, led by a newly assertive Russia and China. Both countries have challenged existing regional settlements, albeit in different ways. Russia’s actions in Ukraine, including its annexation of Crimea, attacked the post-cold war dispensation in Europe and the principle that states should not acquire territory through force. In other areas, Russia has sought to project its power through grey-area interventions or through support for allies such as the Syrian regime. Russia aims to limit the advance of Western institutions and norms in its neighbourhood, and to promote an order based on realpolitik rather than liberal principles.[8] China has acted forcefully to pursue what it regards as core interests in its maritime neighbourhood, including through extensive land reclamation in the South China Sea. It rejected a ruling against it from the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, and has pursued a strategy of legal ambiguity about its maritime claims.[9] China has dramatically increased its defence capabilities in recent years with the apparent goal of achieving military parity with the US, if not dominance, in east Asia.

This newly competitive environment emerged as Western enthusiasm for military intervention waned in the aftermath of costly and unsuccessful wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. President Barack Obama shifted the US in the direction of “light footprint” (albeit extensive) counter-terrorism operations; Trump has followed the same approach, while stepping up the level of force involved. Beyond their lack of success, the United States’ wars in the Middle East and south Asia also undercut its claims that it was upholding a principled, rules-based international order. Even within the West, many people believed that the invasion of Iraq was an act of aggression. Many emerging democracies thought that Western military action in Libya in 2011 went beyond the Security Council’s authorisation of the use of force for civilian protection, and became an illegitimate campaign aimed at regime change. The fallout from the Libya operation was one factor in emerging democracies’ decision to abstain in the UN General Assembly vote on Ukraine in March 2014, as they wanted to distance themselves from what they saw as the double standards of Western powers.[10]

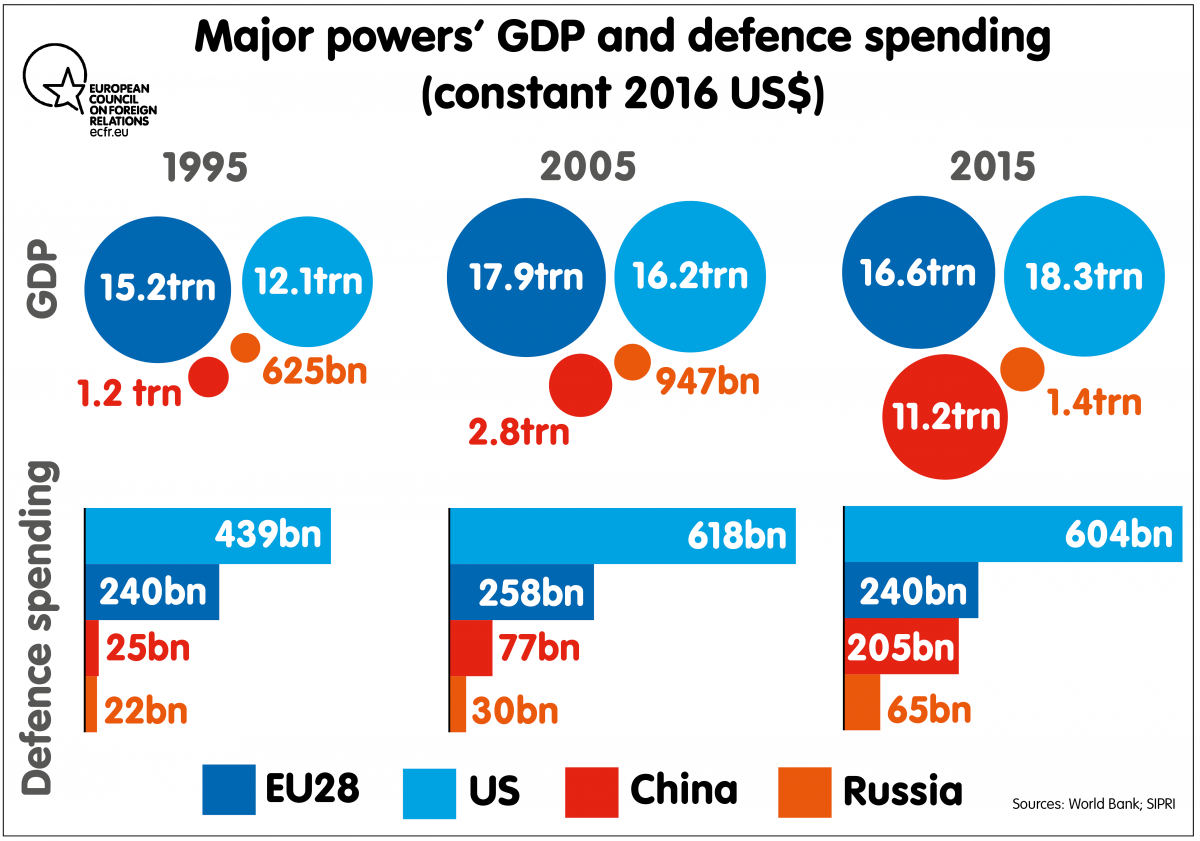

The military priorities of Western states have also diverged since the end of the cold war. The US does not believe that it needs to invest as heavily in the defence of Europe as it once did, and has a much lower stake than the EU in the stability of Europe’s eastern and southern neighbourhoods.[11] Early doubts about Trump’s commitment to NATO have subsided for the moment, while his administration has published a National Security Strategy that focuses heavily on renewed great power competition. Under Trump, the military part of the Western alliance has fared better than many people feared it would during the early months of his presidency.[12] Resisting Russian and Chinese assertiveness – including through the use of sanctions and actions to reinforce the principle of freedom of navigation in open waters – remains a viable Western strategy under US leadership. Indeed, it is disconcertingly unclear whether Europe should worry more about US hawkishness towards or accommodation of rival powers. Nevertheless, Trump could change his mind on Russia (though this would meet with serious opposition in Washington) or take steps to further weaken the US system of alliances in east Asia. Either way, Europe will have to take more responsibility for its own defence – as a condition of continued US engagement, and to promote its interests by helping stabilise neighbouring regions.

Together, these trends point towards a more limited vision of international order than some people hoped for after the end of the cold war. In the 1990s, many Europeans came to see sovereignty as an occasionally regrettable constraint on intervention to halt mass atrocities and efforts to bring those responsible to justice. Now, at a time of assertive rival powers and widespread disorder that is often fuelled by external intervention, it seems more of a priority to reduce the threat or use of force across state borders in violation of the UN Charter. Russian and Chinese opposition means that Western-led military intervention against a state oppressing its own people would be unlikely to gain Security Council authorisation – and could undermine the international rule of law at the same time as it sought to uphold international norms.[13] It may also be harder to win Security Council approval for referrals to the ICC. While the court will continue to play a role in global politics (particularly in cases involving countries that are party to it), the EU should temper its expectations that the ICC will, in the short term, bring members of hostile regimes to justice or have significant influence on active conflicts.

In a world in which great powers embrace a range of different value systems, the EU would be more able to sustain international order if it shifted back towards emphasising the value of sovereignty. In the categories of the Danish political scientist Georg Sørensen, this would mean prioritising a “liberalism of restraint” above a “liberalism of imposition”.[14] The former approach would be more likely to win support from non-Western democracies and to make it easier to build broad coalitions for Western efforts to constrain the use or threat of force by other powers. It would also accommodate the reality that, in a more competitive geopolitical environment, the West will be less able to dictate the terms on which conflicts are settled and may have to accept an imperfect and illiberal peace as the price for ending violence.[15] This effect is clearly visible in the case of Syria: it is hard to see how any peace agreement will involve President Bashar al-Assad’s swift departure from power or measures to bring regime officials to trial for war crimes.

Against this background, Europeans may need to fight a fallback campaign to try to keep their humanitarian vision of multilateralism alive in other ways. The most important is through diplomacy and mediation. Despite attempting to organise a summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, Trump’s strongest effect on international politics has occurred through his rejection of predictable and consistent negotiations aimed at reducing international tensions. Trump’s abandonment of the JCPOA, decision to move the US embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, and apparent embrace of Saudi Arabia’s hard line on Iran are making the Middle East more volatile. The shift in US policy has created a global diplomacy deficit, and the EU should make it a priority to try to fill this gap. In the short term, this means trying to save the JCPOA by encouraging Iran to stay within the deal while trying to limit the effect of renewed US sanctions on European companies.[16] Beyond this, the EU may need to think creatively about how to bolster the global non-proliferation regime and make a greater effort to de-escalate tensions and promote peace in conflicts from Yemen to Ukraine.

The EU should also fight to support humanitarian and human rights principles within the UN system, at a time when they are increasingly being challenged.[17] Even in conflicts in which great powers are not involved through the support of proxies, the Security Council is finding it harder to agree on peacekeeping interventions.[18] Meanwhile, China has become increasingly active at the UN in promoting a state-centric vision of human rights and in limiting the organisation’s human rights activities through budget cuts.[19] With a US administration that is less committed to multilateralism than its predecessor, it is up to Europe to try to build broad coalitions that can counteract these trends. The EU should also work with like-minded countries to reinforce standards for upholding the rule of law in armed conflict.[20] This effort is especially important at a time when widespread violations of international humanitarian law, the growing role of non-state groups as government proxies, and the evolution of transnational counter-terrorism campaigns – many of which rely on armed drones – are eroding these standards.[21]

The EU will be best able to fight a normative battle against the conceptions of international order presented by Russia, China, and perhaps the US if it presents a convincing case for its own model. Strengthening the EU’s internal cohesion and resolving cleavages within European countries will allow the EU to be more resilient in the face of external campaigns of disruption.

Trade and investment

The development of open, rules-based economic interaction between states is at the heart of the European vision of international order. Taken as a whole, the growth in international trade since the second world war has had impressive economic benefits. Between 1950 and 2015, global average real income per head rose nearly fivefold, and the proportion of the world’s population in extreme poverty fell from 72 percent to 10 percent.[22] In the decades following the 1980s, there was a particularly large increase in cross-border flows of goods, services, and finance.[23] But it is now clear that the Western-led economic order has been, in one sense, too successful and, at the same time, not successful enough.[24] The rising wealth of the developing world has made the West’s dominant role in the economic order unsustainable. Meanwhile, the gains from the market-driven globalisation of recent decades were unequally distributed in a way that has undermined the legitimacy of the entire order.

The liberal order put in place after the second world war was meant to provide an international infrastructure that allowed states to pursue progressive policies at home. The corollary of an open world economy was that governments would stabilise and protect market economies at home through the development of welfare states.[25] However, in the last two decades, as globalisation has accelerated, this link appeared to break. Many Europeans and Americans now see economic openness as benefiting emerging economies and privileged Westerners at the expense of large sectors of the Western working and middle classes (although, in much of Europe, the persistence of social spending moderates this effect). While many economists believe that technological change drives much of the loss of manufacturing jobs in Western societies, recent research suggests that the entrance of China and other emerging economies into the global trading system has also contributed significantly.

Trump has acted on this perception by withdrawing the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement and calling for the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement. More alarmingly for Europe, he has also moved to undermine the essential basis of the rules-based multilateral trading system by attacking the WTO. Trump has repeatedly called the WTO a “disaster” for the US.[26] Under his leadership, the US has held up the appointment of judges to the WTO’s appellate body, threatening to bring the organisation’s dispute settlement mechanism to a halt. Trump has also imposed unilateral tariffs on steel and aluminium under a spurious “national security” justification that weakens the system’s credibility, and promised further tariffs aimed at China without following WTO procedures – raising fears of an all-out trade war between the world’s two leading economies.

The irony is that Trump’s pushback against free trade comes at a time when there is growing acceptance in both Europe and the US that China has exploited the international trading system to its advantage.[27] China’s accession to the WTO did not lead to further steps in the progressive opening of its economy, and the WTO system has proved unsuccessful in regulating asymmetries in China’s approach to trade as the country’s income has increased. The EU, the US, and other economic powers such as Japan might still be able to work together within the WTO rules to seek greater reciprocity in economic relations with China. But faced with a threat to the equal-access trading regime of the WTO, the EU’s priority should be preserving the rules-based system.[28] The EU should combine its offer to work with the US in correcting imbalances in global trade with a clear statement that it would oppose moves designed to weaken the WTO. The size of the EU market gives it the power to stand up credibly to the US if need be.

In any case, many of Trump’s complaints are backward-looking and fail to address the most urgent current concerns. Shifting patterns of global trade, including the growth of global supply chains, have brought new issues such as investment and trade in intermediate goods and services to the top of the agenda.[29] An earlier ECFR report suggested that the construction of an EU-wide system of investment screening is now the priority in European economic relations with China.[30] These issues have been the focus of a wave of bilateral and regional treaties that provide the EU with the opportunity to pursue a vision of international trade that protects its values. European participation in recent bilateral or regional treaties is predicated on their inclusion of regulatory standards in areas such as labour rights, environmental standards, and data protection. In this way, these treaties add an additional layer of social protection to the WTO system – although critics suggest their impact has been limited so far.[31]

At the same time, as an economic heavyweight the EU is able to unilaterally create regulatory standards that exert a broader international influence through what has been called the “Brussels effect”.[32] The European market is so large that many exporters around the world voluntarily and comprehensively comply with the standards it sets in areas such as food safety, consumer protection, chemicals, and airline emissions. This is because it is often too costly to manufacture different product lines for different markets.

Yet, in other ways, the EU has been forced to come to terms with the fragmentation of the international economic order as non-Western powers, led by China, increase their influence. The creation of institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the BRICS-based New Development Bank has challenged the role of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Indeed, the veto power that China holds in the AIIB through its voting share mirrors the role of the US in the IMF. According to their supporters, these organisations complement rather than replace traditional international financial institutions for emerging powers, which gain access to bodies more focused on their needs.[33]

Western observers feared that these new financial institutions would undercut the conditionality of the World Bank and the IMF by lending without imposing requirements in areas such as governance and transparency. However, there is growing recognition that the record so far is more nuanced, with the AIIB having aligned more closely than expected with the policies and standards of traditional multilateral development banks.[34] Moreover, Western development assistance has sometimes promoted human rights standards more in rhetoric than reality. There seems greater reason for concern about China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which appears tied to a narrower vision of Chinese economic and strategic advantage.[35] Nevertheless, as reflected in the reach of this initiative, China’s economic power is too substantial to be contained by European policy

Global challenges: Migration and climate change

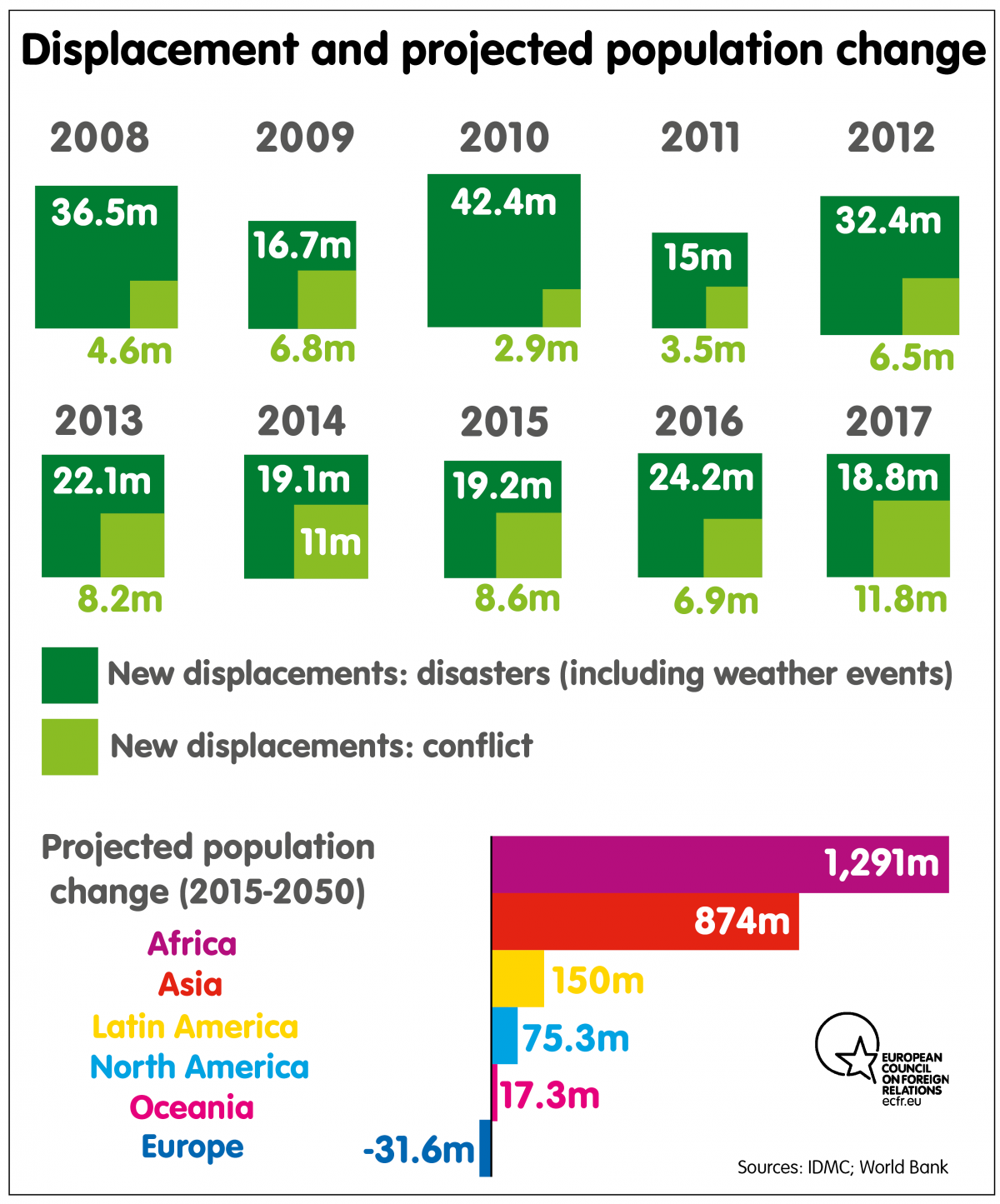

Even when the liberal international order was at it strongest, there were some areas in which it clearly remained incomplete. One of its most obvious weaknesses was that it did not include an adequate regime for governing the large-scale movement of people across borders. Refugees have continued to suffer from a lack of international protection, and there has never been an effective framework that allocates responsibility for meeting their needs. The 1951 Refugee Convention established the principle of non-refoulement, which protects refugees from forcible return to a country in which they would face persecution. This principle remains at the core of refugee protection but, in other respects, the convention has proven increasingly unfit to cope with changing patterns of displacement. The convention only covers those who are fleeing persecution (as opposed to, for instance, endemic disorder or natural disaster); is geared towards the provision of relief rather than more long-term opportunities; and leaves countries that refugees reach first to bear most of the responsibility for helping them.[36] This regime is now struggling to deal with the highest level of displacement in the history of the convention. Most refugees live in a small number of developing countries, which cannot afford to provide them with the services and economic opportunities they need.

More broadly, there has been a rapid increase in migration worldwide in the last two decades, in line with the development of other facets of globalisation, such transportation and communication. In 2017, there were an estimated 258 million international migrants, accounting for 3.4 percent of the global population.[37] No issue has done more than migration to make citizens of Western countries see international openness as a threat rather than a source of opportunities. This trend has increasingly driven governments in the developed world to adopt an approach to irregular migration that aims to, as far as possible, deter asylum seekers and other migrants from reaching their countries. They have done so by exploiting gaps in the regime of international protection, complying with the law while leaving vulnerable people with inadequate protection.[38] There is a need for an international regime that offers better prospects to those who are forcibly displaced, but that does so in a way that is politically sustainable among electorates in developed democracies.

The classic multilateral method of addressing global challenges such as mass displacement is to negotiate a new international treaty that imposes binding responsibilities on all parties. But in the case of refugees and migration, this path appears blocked. States have no appetite for taking on new responsibilities under the Refugee Convention, and few developed countries have signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Migrant Workers. The Refugee Convention’s definition of refugees is plainly insufficient, but it is likely that opening the convention to renegotiation would lead to fewer protections.[39] Instead, the most promising path towards collective action on migration seems to lie in a newer and more informal vision of global governance based on pragmatism, voluntary adherence, and a diversity of responsible actors.

This year, UN member states are due to adopt two global compacts on refugees and migration respectively – non-binding frameworks that aim to set out guiding principles for collective action. They will be based on the 2016 New York Declaration, which reaffirmed that protecting refugees is a shared international responsibility and pledged “robust support” to countries affected by large-scale migration. This approach builds on the Nansen Initiative on migration caused by natural disasters. Led by a coalition of states from different regions – with the extensive involvement of civil society groups, businesses, and other organisations – the initiative produced an Agenda for Protection that has been widely endorsed.[40] Following this model, refugee and development scholars Alexander Betts and Paul Collier have called for an approach to refugee protection based on pragmatic partnerships involving both states and non-state actors rather than a new or revised legally binding instrument.[41] Similarly, political theorist Michael Ignatieff has identified the response to refugees as exemplifying “a genuine crisis of the universal amidst a return of the sovereign”, arguing that an approach based on generosity and compassion will be more effective than one based on legal obligation.[42] In his words, “maintaining public support to assist strangers and refugees is more likely to succeed if the appeal is cast in the language of the gift, rather than the language of rights”.[43]

There is a precedent for this kind of an inclusive, voluntary approach to global governance in the world’s response to the other great collective challenge of our time: climate change.[44] Climate change has long spurred migration, an effect that will likely become increasingly apparent as temperatures and sea levels rise. In 2015, a worldwide “high-ambition coalition” of states forged the 21st Conference of Parties (COP21) agreement as a hybrid model combining voluntary national commitments with obligations on transparency and reporting.[45] Based on the aspirational principle that parties will increase their commitments over time, the agreement includes a significant role for non-state entities such as businesses, civil society groups, and local governments. These diverse participants will help the COP21 regime survive Trump’s decision to withdraw the US from the agreement (just as he withdrew it from negotiations on the Global Compact for Migration). The “We Are Still In” collection of US states, cities, and businesses that have pledged to continue working towards the US commitment under COP21 would, if treated as a country, have the world’s third-largest economy (after the wider US and China).[46]

This evolving approach to global governance has won support from both the West and emerging powers such as India and China due to its voluntary nature and its embrace of the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”.[47] The EU can contribute to its success first and foremost by setting an example, adhering to its targets, and embracing a share of global responsibilities that will be seen as fair. On migration, this will require the EU to find a sustainable balance between showing Europeans that it can control Europe’s borders while offering some legal pathways for immigration. The aim should be to present immigration as a managed and fair process that meets European needs rather than as something to be halted at all costs. At the same time, the EU should increase investment in education and family planning to try to limit population growth in neighbouring regions and hence reduce migratory pressure. On climate change, the EU should supplement its current commitments with a carbon border-adjustment tax to encourage adherence overseas, and make sure that European businesses do not suffer for their efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Cyberspace

Although policymakers often treat it as a self-contained domain, cyberspace is a dimension of the contemporary world that cuts across all the areas discussed in this report.[48] Indeed, cyber security increasingly preoccupies governments everywhere. Having been largely neglected in the early days of the internet, cyber security concerns have become increasingly prominent in recent years due to attacks on countries’ infrastructure, commercial enterprises, and elections. At the same time, the internet is revolutionising the global economy: it is the world’s most important piece of infrastructure and is set to underpin all infrastructure.[49] Having evolved in a lightly regulated way, the internet has now become the focus of a global debate about the norms that should govern its operations, as people take in the revolutionary impact it is having on both governance and individuals’ private lives.

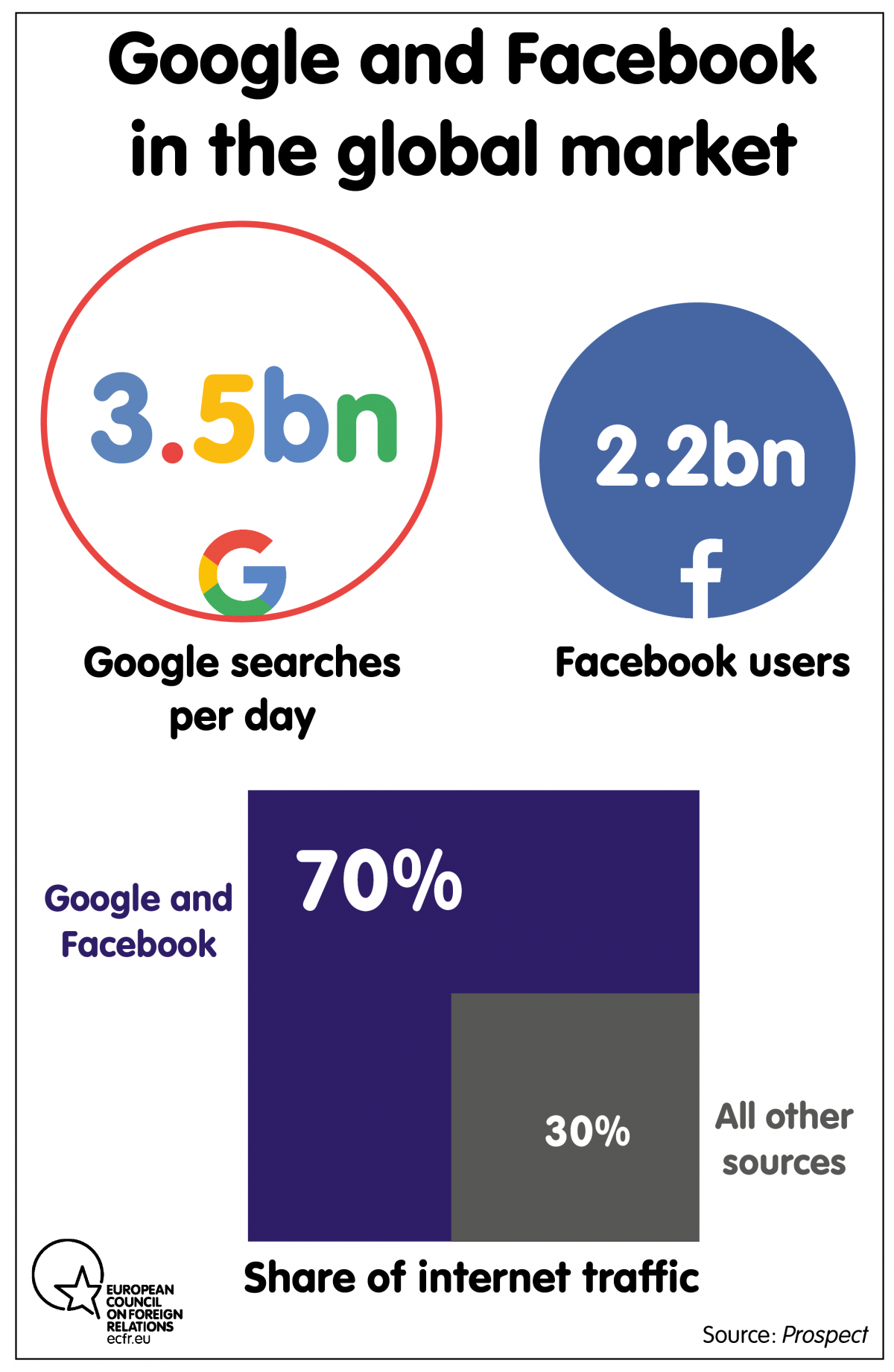

The governance of cyberspace is an important part of the international order – one in which the principles of openness, security, and inclusivity are at stake.[50] The revelations about data surveillance by the US National Security Agency and other intelligence services, and of the use of data gathered by Facebook, Google, and other companies, has eroded users’ trust in the protection of their privacy online. A handful of companies based in the US now constitute a vital part of the public sphere in countries around the world, and unaccountable algorithms play a significant role in determining people’s financial and life opportunities.[51] At the same time, China’s “Great Firewall” and Russian efforts to control online content herald a future in which a growing number of countries are likely to attempt to create segregated national internets.[52] Efforts to agree on international principles for state behaviour in cyberspace through a UN-sponsored process have faltered.[53] There is a danger that the global nature of the internet, with all the advantages it has for economic growth and free expression, could be further undermined if people in democratic states come to see online connectivity as a more of a threat than a source of opportunities.

It would fit well with the EU’s interests and values to take a leading role in promoting a liberal internet that remains open but offers better protection for users and national security. Europe can stake out a global position that counterbalances both the Sino-Russian sovereigntist approach and US acquiescence to the loosely regulated operation of digital monopolies.[54]

In one respect, the EU has already established itself as a global standard-setter in internet regulation. Its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), implemented in May 2018, provides EU citizens with greater control over how companies around the world handle their data. In an example of the Brussels effect described above, some non-European companies have adopted these rules for all their customers, while some non-European countries have accepted the GDPR as the gold standard for data protection.[55] Facebook said it would comply with the regulation “in spirit” for all its customers, although it also gave itself the option of applying looser rules for non-European users by transferring their contracts away from the company’s international headquarters in Ireland. The European Commission has also begun to develop a policy on “fake news”, centring on a call for companies to adopt a voluntary code of conduct on online disinformation.[56]

Despite the importance of these measures, they still fall short of a comprehensive approach that takes account of all the areas cyber policy affects. Europe lacks an integrated vision of how to balance the often competing demands of commercial interests, human rights, national security, and public consent in internet governance.[57] For example, it does not have a considered position on the extent to which political actors should be allowed to exploit personal data. The EU essentially treats personal data as a privacy issue, but it is also a resource that potentially has enormous value to global public goods in areas such as healthcare, security, and environmental protection. European countries should work towards the development of an international system that secures, while distributing the benefits of, personal data.[58]

The EU also has a key role as a supporter of the principle of multi-stakeholder governance of the internet, in the face of new developments such as the sharing economy and the internet of things.[59] The US was a strong backer of the multi-stakeholder principle under Obama, passing authority over domain name administrator the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to a multi-stakeholder coalition in 2016. But Trump has adopted a very different line. There are indications that his administration may look for ways to reverse the handover of ICANN (although it is unclear how this could be achieved).[60] Since US advocacy was important in persuading emerging democracies such as India, Brazil, and South Africa to support a multi-stakeholder approach to internet governance, there is a danger that the Trump administration’s position will have an international ripple effect.

In 2017, states taking part in the UN-sponsored Group of Governmental Experts failed to reach an agreement on how international law applies to offensive cyber operations – particularly on states’ legal right to respond to cyber attacks. In any case, some of the states involved appear to have ignored the norms agreed on earlier in the process, including those on cyber attacks against critical infrastructure. In the absence of international agreement, groups of like-minded states can best advance the formation of norms by developing their own guidelines on applying international law in this area. EU member states should coordinate with allies and partners such as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Japan in developing standards that can guide state practice on issues such as the definition of an armed attack in cyberspace and the appropriate use of countermeasures.[61] Some of the most difficult strategic questions raised by offensive cyber operations concern actions that fall short of a conventional armed attack yet rise above the level of intelligence operations because they have an effect on political or commercial life. The challenges here include defining the threshold at which an action counts as an unlawful intervention, and finding a way to deter attacks that is both effective and compatible with the principles of democratic, law-abiding societies.

Conclusion: Putting the defence of liberal order at the heart of the European Global Strategy

The EU can best support the preservation of a rules-based system by promoting an adapted vision of international order that takes account of recent developments and new challenges. The EU should place an updated idea of liberal order at the centre of its Global Strategy, and build the capacity to implement this strategy.

In doing so, the EU should follow an approach that aims to reconcile some of the tensions between sovereignty and international order that have become problematic in recent years due to the rise of assertive illiberal powers, inconsistencies in Western practice, and a pervasive belief among Western electorates that globalisation is more a threat than an opportunity. A liberal order reinvented along the lines suggested above would offer greater recognition of the value of sovereignty by strengthening constraints on unlawful intervention; providing greater scope for Europe to reaffirm its standards through regulation and trade; and accepting voluntary commitments as a basis for some international agreements. The EU would offset this with a renewed commitment to multilateralism as the best way of securing Europeans’ security and prosperity; attempts to develop new norms for a more connected world; and support for the inclusion of businesses and civil society groups as participants in the order.[62]

In practical terms, this agenda gives rise to several priorities. Firstly, the EU needs to focus on its resilience as the keystone of a rules-based and liberal order. This involves major initiatives in several areas:

- Security: Step up defence spending while pooling and sharing resources, to establish strategic autonomy at a time when the US commitment to European security is fading. European countries could strengthen their coordination within NATO by establishing a European caucus and outside the organisation by developing intra-European coordination, particularly through the nascent European Intervention Initiative.[63]

- Economics: Invest in a new economic settlement at home to help those who feel left behind by globalisation, while developing tougher measures to stop China and other emerging players from creating an uneven playing field, including through investment screening.

- Migration: Build up the EU’s ability to police its external border as a complement to managed pathways for legal migration.

- Internet governance: Introduce regulation that creates a better balance between security, privacy rights, commercial opportunities, and the welfare of society as a whole.

Secondly, Europe needs to help compensate for the global diplomacy deficit by far more actively reaching out to other players, as well as pushing for a mediation role in crises and conflicts in the European neighbourhood:

- Working in coordination with the European External Action Service (EEAS), member states should reach out to other great powers and swing states such as Brazil, India, and Indonesia on essential questions of order – and place the defence of the rules-based order at the heart of EU summits and meetings.

- The EU should make better use of its financial engagement with many of the world’s most troubled states – including Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Ukraine – to play a greater political role in support of stabilisation.

Thirdly, the EU should make greater use of its economic leverage to preserve the rules-based order. In this, it should:

- Support the COP21 agreement by further promoting trade deals that incorporate environmental requirements, and by implementing a carbon border-adjustment tax at the EU’s borders.

- Use the size of the EU market to define and export standards for better regulation of the internet.

- Create the space to establish decision-making power on questions of order by pushing back against the extra-territoriality of US sanctions. In the short term, the EU should take steps such as establishing euro credit lines and special purpose vehicles to assist companies doing business with Iran, while pursuing measures to reduce the impact of US sanctions.[64] The EU should also set up an action task force that, bringing together all relevant parts of EU institutions, explores longer-term options for establishing greater financial independence from the US.

Fourthly, the EU should develop a series of sectoral strategies for preserving the rules-based order – in trade, arms proliferation, and environmental protection. These strategies should involve a set of complementary instruments, including trade, defence, diplomacy, development, financial, and regulatory tools. The EEAS should coordinate the use of the tools, but sub-groups of member states should create them. Such an approach would improve the links between EU institutions and member states in these strategies.

To implement this agenda, the EU will need to overhaul its ways of working. Internally, it will need to find a method for operating with the flexibility and speed required for greater diplomatic engagement, while keeping the collective weight of the EU behind its initiatives. Coordinating EU efforts with the United Kingdom after Brexit will also be important. Externally, the EU will need to make an especially large investment in its relations with like-minded powers. Conversely, it will need to develop a more independent posture towards the US. The EU should continue to cooperate with the US wherever possible, but it should put its commitment to the rules-based order above its traditional instinct to follow the American lead.

Some Europeans will worry that an independent and sometimes defiant attitude to the US will jeopardise the security relationship on which the EU continues to depend. But Trump has shown clearly that he does not reward concessions. Under his leadership, the United States’ security policy reflects its calculation of its own interests rather than any concern for repaying allies’ loyalty. The EU can best manage its relationship with the US and its support for a rules-based international system if it develops and acts on a sense of itself as an independent strategic actor. Europe needs to set its own course to secure the world order it wants.

Acknowledgements

This paper was made possible by a grant from the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. We would like to thank Antti Kaski for commissioning the project, and Sini Paukkunen and Ossi Piironen for seeing it through. As our research involved interviews with leading thinkers in the areas the report covers, we would like to thank the following people for their insights: Edward Luce, Edward Luttwak, Parag Khanna, Vincenzo Iozzo, Mary Kaldor, Carl Bildt, Yascha Mounk, Pankaj Mishra, Cathy O’Neil, Michael von der Schulenburg, Kelly Greenhill, Joseph Nye, Anu Bradford, and Martin Wolf. Recordings of these “End of the World” interviews are available at https://ecfr.eu/podcasts/end_of_the_world. Archie Hall was the organising genius behind the podcasts who not only drove the selection of guests and content but even designed a logo, mug, and social-media campaign to widen participation in the debate. We would also like to think Eneken Tikk for her help on cyber policy. We benefited from the chance to discuss an early version of our findings at a seminar at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs and at a workshop at the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. In particular, we would like to thank Sophie Eisentraut for her perceptive response to our presentation.

This paper looks at many of the areas studied by our ECFR colleagues; we benefited greatly from their writings and suggestions. In particular, we would like to thank Susi Dennison, Sebastian Dullien, Ulrike Franke, Ellie Geranmayeh, Richard Gowan, Jonathan Hackenbroich, Josef Janning, Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, Jeremy Shapiro, and Pawel Zerka, as well as ECFR council member Ivan Krastev, for advice and comments on earlier drafts. Naturally, all responsibility for the final paper lies with the authors. Chris Raggett skilfully edited the paper and designed the graphics.

About the authors

Anthony Dworkin is a senior policy fellow at ECFR focusing on human rights, democracy, and justice. He is also a visiting lecturer in the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po. His earlier publications for ECFR include “Europe’s new counter-terror wars” (2016) and “International justice and the prevention of atrocity” (2014). He was formerly executive director of the Crimes of War Project.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of ECFR. He writes a syndicated column on global affairs for Project Syndicate and his essays have appeared in numerous other publications. Mark is the author of Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century (2005) and What Does China Think? (2008), and the editor of Connectivity Wars (2016). He presents ECFR’s weekly World in 30 Minutes podcast. He was Chairman of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Geo-economics until 2016.

[1] G. John Ikenberry, “The end of liberal international order?”, International Affairs, January 2018.

[2] Amitav Acharya, “After Liberal Hegemony: The Advent of a Multiplex World Order”, Ethics and International Affairs, September 2017, available at https://www.ethicsandinternationalaffairs.org/2017/multiplex-world-order/.

[3] Walter Russell Mead, “The Return of Geopolitics”, Foreign Affairs, May-June 2014.

[4] ECFR interview with Pankaj Mishra, August 2017, available at https://soundcloud.com/ecfr/the-end-of-the-world-8-interview-with-pankaj-mishra.

[5] Mark Leonard (ed.), “Connectivity Wars”, European Council on Foreign Relations, January 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/page/-/Connectivity_Wars.pdf; ECFR interview with Parag Khanna, August 2017, https://ecfr.eu/podcasts/episode/the_end_of_the_world_3_interview_with_parag_khanna.

[6] For a collection of essays that includes a number of European views, see Trine Flockhart et al. (eds), “Liberal Order in a Post-Western World”, Transatlantic Academy, May 2014, available at http://www.transatlanticacademy.org/sites/default/files/publications/TA%202014report_May14_web.pdf.

[7] On the distinction between international order and US or Western hegemony, see Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, “La chute de l’ordre international liberal?”, Esprit, June 2017, available at https://esprit.presse.fr/article/lafont-rapnouil-manuel/la-chute-de-l-ordre-international-liberal-39478.

[8] Kadri Liik, “What does Russia want?”, ECFR, 26 May 2017, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_what_does_russia_want_7297.

[9] Simon Chesterman, “Asia’s Ambivalence about International Law and Institutions: Past, Present and Futures”, European Journal of International Law, December 2016, pp. 972-73.

[10] See Oliver Stuenkel, “Why Brazil has not criticized Russia over Crimea”, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre, May 2014, available at https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/180529/65655a04cd21b64dbcc9c8a823a8e736.pdf.

[11] Dina Pardijs and Jeremy Shapiro, “The transatlantic meaning of Donald Trump: A US-EU Power Audit”, ECFR, September 2017, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/the_transatlantic_meaning_of_donald_trump_a_us_eu_power_audit7229.

[12] ECFR interview with Joseph Nye, October 2017, available at https://soundcloud.com/ecfr/the-end-of-the-world-12-interview-with-joseph-nye.

[13] Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, “Syria strikes: the politics of legality and legitimacy”, War on the Rocks, 1 May 2018, available at https://warontherocks.com/2018/05/syria-strikes-the-politics-of-legality-and-legitimacy/.

[14] Georg Sørensen, A Liberal World Order in Crisis (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011), pp. 54-65.

[15] Barry R. Posen, “Civil Wars and the Structure of World Power”, Daedalus, Autumn 2017.

[16] Ellie Geranmayeh, “After Trump’s Iran decision: Time for Europe to step up”, ECFR, 9 May 2018, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_after_trump_iran_decision_time_for_europe_to_step_up (hereafter, Geranmayeh, “After Trump’s Iran decision”).

[17] Richard Gowan, “Separation anxiety: European influence at the UN after Brexit”, ECFR, May 2018, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/separation_anxiety_european_influence_at_the_un_after_brexit.

[18] Jean-Marie Guéhenno, “The United Nations and Civil Wars”, Daedalus, Winter 2018, p. 191.

[19] Colum Lynch, “At the U.N., China and Russia Score Win in War on Human Rights”, Foreign Policy, 26 March 2018, available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/03/26/at-the-u-n-china-and-russia-score-win-in-war-on-human-rights/.

[20] ECFR interview with Mary Kaldor, available at https://soundcloud.com/ecfr/the-end-of-the-world-5-interview-with-mary-kaldor.

[21] For one suggestion of a possible new approach, see Anthony Dworkin, “Individual, Not Collective: Justifying the Resort to Force Against Members of Non-State Armed Groups”, International Law Studies, November 2017, available at http://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ils/vol93/iss1/16/.

[22] Martin Wolf, “The long and painful journey to world disorder”, Financial Times, 5 January 2017, available at https://www.ft.com/content/ef13e61a-ccec-11e6-b8ce-b9c03770f8b1.

[23] “Global flows in a digital age”, McKinsey Global Institute, April 2014, available at https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/global-flows-in-a-digital-age.

[24] ECFR interview with Martin Wolf, September 2017, available at https://soundcloud.com/ecfr/the-end-of-the-world-14-interview-with-martin-wolf.

[25] G. John Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis and Transformation of the American World Order (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), pp. 174-79.

[26] See Donald Trump, “Remarks in Listening Sessions with Representatives from the Steel and Aluminium Industry”, White House, 1 March 2018, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-listening-session-representatives-steel-aluminum-industry/.

[27] François Godement and Abigaël Vasselier, “China at the gates: A new power audit of EU-China relations”, ECFR, December 2017, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/china_eu_power_audit7242 (hereafter, Godement and Vasselier, “China at the gates”); Kurt M.Campbell and Ely Ratner, “The China Reckoning: How Beijing Defied American Expectations”, Foreign Affairs, March 2018.

[28] Sebastian Dullien, “Trade conflict with the U.S. is the only way to protect free trade”, ECFR, 23 February 2018, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_trade_conflict_with_the_u.s._is_the_only_way_to_protect_free_tra.

[29] Richard Baldwin, “The World Trade Organization and the Future of Multilateralism”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2016.

[30] Godement and Vasselier, “China at the gates”.

[31] “Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) chapters in EU Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)”, European Commission non-paper, 11 July 2017, available at http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/july/tradoc_155686.pdf; see also Mirela Barbu et al, “A Response to the Non-paper of the European Commission on Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) chapters in EU Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)”, Warwick University, 26 September 2017, available at https://warwick.ac.uk/about/partnerships/europe/events/tsd/a_response_to_the_nonpaper_26.09.17.pdf.

[32] ECFR interview with Anu Bradford, October 2017, available at https://soundcloud.com/ecfr/end-of-the-world-13-anu-bradford.

[33] Deepa M. Ollapally, “India and the International Order: Accommodation and Adjustment”, Ethics and International Affairs, March 2018, pp. 67-68 (hereafter, Ollapally, “India”).

[34] Fleur Huijskens, Richard Tucsanyi and Balazs Ujvari, “How Europe can use the AIIB to influence China”, MERICS, 10 August 2017, available at https://www.merics.org/en/blog/how-europe-can-use-aiib-influence-china.

[35] Angela Stanzel, “China’s Belt and Road – new name, same doubts?”, ECFR, 19 May 2017, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_chinas_belt_and_road_new_name_same_doubts.

[36] Alexander Betts and Paul Collier, Refuge: Transforming a Broken Refugee System (London: Allen Lane, 2017), pp. 41-55 (hereafter Betts and Collier, Refuge).

[37] “Population Facts”, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, December 2017, available at http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/populationfacts/docs/MigrationPopFacts20175.pdf.

[38] Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nikolas F. Tan, “The End of the Deterrence Paradigm? Future Directions for Global Refugee Policy”, Journal on Migration and Human Security, 2017, available at http://jmhs.cmsny.org/index.php/jmhs/article/view/73.

[39] ECFR interview with Kelly Greenhill, September 2017, available at https://soundcloud.com/ecfr/the-end-of-the-world-12-interview-with-kelly-greenhill.

[40] Susan F. Martin, “New Models of International Agreement for Refugee Protection”, Journal on Migration and Human Security, 2016, available at http://cmsny.org/publications/jmhs-new-refugee-protection-models/.

[41] Betts and Collier, Refuge, pp. 207-224.

[42] Michael Ignatieff, The Ordinary Virtues (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), p. 216 (hereafter Ignatieff, Ordinary Virtues).

[43] Ignatieff, Ordinary Virtues, p. 214.

[44] For a similar argument that migration and climate change are together seeing the early development of a new model of global governance, see Mireille Delmas-Marty, “Migrants : ‘Faire de l’hospitalité un principe’”, Le Monde, 12 April 2018, available at http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2018/04/12/migrants-faire-de-l-hospitalite-un-principe_5284526_3232.html.

[45] Robert C. Orr, “The New Climate Governance Paradigm”, in “Innovations in Global Governance”, Council on Foreign Relations, September 2017, p. 42, available at https://cfrd8-files.cfr.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/Memo_Series_Kahler_et_al_Global_Governance_OR_1.pdf.

[46] Stephen Leahy, “Half of U.S. Spending Power Behind Paris Climate Agreement”, National Geographic, 15 November 2017, available at https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/11/were-still-in-paris-climate-agreement-coalition-bonn-cop23/.

[47] Ollapally, “India”, p. 66.

[48] ECFR interview with Eneken Tikk, March 2018.

[49] ECFR interview with Carl Bildt, August 2017, available at https://soundcloud.com/ecfr/the-end-of-the-world-6-interview-with-carl-bildt.

[50] “One Internet”, Global Commission on Internet Governance, June 2016, available at https://www.cigionline.org/publications/one-internet (hereafter, “One Internet”).

[51] ECFR interview with Cathy O’Neill, September 2017, available at https://soundcloud.com/ecfr/the-end-of-the-world-9-interview-with-cathy-oneil.

[52] Emily Parker, “Russia Is Trying to Copy China’s Approach to Internet Censorship”, Slate, 4 April 2017, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2017/04/russia_is_trying_to_copy_china_s_internet_censorship.html.

[53] Eneken Tikk and Mika Kerttunen, “The Alleged Demise of the UN GGE: An Autopsy and Eulogy”, Cyber Policy Institute, December 2017, available at http://cpi.ee/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/2017-Tikk-Kerttunen-Demise-of-the-UN-GGE-2017-12-17-ET.pdf.

[54] George Soros, “The Social Media Threat to Society and Security”, Project Syndicate, 14 February 2018, available at https://www.project-syndicate.org/bigpicture/should-internet-monopolies-be-tamed.

[55] Mark Scott and Laurens Cerulus, “Europe’s new data protection rules export privacy standards worldwide”, Politico Europe, 31 January 2018, available at https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-data-protection-privacy-standards-gdpr-general-protection-data-regulation/.

[56] “Tackling online disinformation: Commission proposes an EU-wide Code of Practice”, European Commission, 26 April 2018, available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-3370_en.htm.

[57] ECFR interview with Eneken Tikk, March 2018.

[58] Eyal Benvenisti, “State Sovereignty and Cyberspace: What Role for International Law?”, Tel Aviv University, 30 August 2017, available at http://globaltrust.tau.ac.il/state-sovereignty-and-cyberspace-what-role-for-international-law/.

[59] “One Internet”, pp. 87-92.

[60] John Hendel, “Make the internet American again? Trump pick opened the door”, Politico, 23 January 2018, available at https://www.politico.com/story/2018/01/23/trump-commerce-pick-internet-oversight-reversal-305178.

[61] For an account of the GGE process highlighting these questions, see Michael Schmitt and Liis Vihul, “International Cyber Law Politicized: The UN GGE’s Failure to Advance Cyber Norms”, Just Security, 30 June 2017, available at https://www.justsecurity.org/42768/international-cyber-law-politicized-gges-failure-advance-cyber-norms/.

[62] For an article that identifies some of these principles as elements of President Macron’s political thinking, see Paul Zajac and Benjamin Haddad, “Emmanuel Macron’s Critique of Pure Liberalism”, Foreign Policy, 20 April 2018, available at http://foreignpolicy.com/2018/04/20/emmanuel-macrons-critique-of-pure-liberalism/.

[63] Nick Witney, “Macron and the European Intervention Initiative: Erasmus for soldiers?”, ECFR, 22 May 2018, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_macron_and_the_european_intervention_initiative_erasmus_for_sold.

[64] For further details on these and other possible steps, see Geranmayeh, “After Trump’s Iran decision”.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.