Trump, Biden, and Europe’s place in the Africa great power competition

European activities in Africa risk unwittingly drifting onto territory contested by the US and China on their own terms

The distinguishing feature of the Trump administration’s approach to Africa is its framing of the continent as venue for great power competition. Instead of emphasising the positives between the United States and African countries, national security adviser John Bolton raised China over 15 times when presenting the US Africa Strategy in December 2018. He was at pains to stress that “countries that repeatedly vote against the US in international forums, or take actions counter to US interests, should not receive generous American foreign aid.”

The cold war-style approach embodied in US strategy was followed by covid-19, which exacerbated the zero-sum logic in the US-China dynamic. In Africa this affirmed perceptions among governments that this is the now the fundamental element of geopolitics with which they need to engage.

Not all international activity in Africa rise to the level of great power competition. Unlike in the cold war, the US is not squaring off against its rival via proxy wars. Rather, the sphere has been delineated in response to the tools China has been deploying to increase its footprint on the continent. This primarily encompasses the connectivity realm: loans, infrastructure, telecommunications, and China’s general steady advance of state-backed private enterprise into acquiring a dominant market share. Other traditional US activity – security assistance, peacekeeping, humanitarian and development assistance, and – until recently – health – escape geopolitical import. The prism of great power competition is not yet evoked in these areas.

What does this mean for Europe?

That this distinction has emerged matters for Europe. Much of the EU’s flagship policy document on Africa, “Towards a Comprehensive Strategy with Africa”, relates to connectivity issues. In other words, they stray into the new Great Game territory. Having entered this highly charged sphere, European initiatives conceived without Great Game politics in mind become subject to interpretation – and as partisan on the side of the US. Quite unintentionally, Europe’s technocrats may find themselves unwilling participants in the new struggle.

The US cold war-style approach affirmed perceptions among African governments that this is now a fundamental element of geopolitics

A second by-product is the possible inflation of the African geopolitical market. African leaders and others decry the cold war’s legacy as an unalloyed negative for the continent. However, the dynamic of the cold war meant that when African states sought attention and investment, the cold war meant they were more likely to receive it. A similar dynamic may emerge again. For Europe, this means that its offer to the continent must contend with increased competition.

Finally, increasing weaponisation of multilateral instruments by both by China and the US works to the particular detriment of African needs in the covid-19 context. This manifests in the failure to rally behind COVAX, the multilateral platform for covid-19 vaccination, but also through using the Bretton Woods institutions to score points. On the first issue, COVAX is a way of diversifying investment and risk sharing in a covid-19 vaccine. But it is also a means of supporting low-income countries that cannot self-finance vaccine development; a keen interest of Africa’s. China signed on to the COVAX platform at the eleventh hour but to date the US has absented itself.

On the second issue, the disastrous economic knock-on effects of covid-19 in Africa can also only be feathered through multilateral – in this case Bretton Woods – means. The most powerful fiscal weapon at the International Monetary Fund’s disposal, Special Drawing Rights, or “paper gold”, could have been issued to increase Africa’s asphyxiated fiscal breathing space. Because these SDRs flow to all IMF members an overspill benefit might have accrued to Trump administration foes: Iran, Russia, and China. Rather than take this in its stride, the Trump administration exercised its IMF veto behind the scenes, throttling an initiative backed by Europe and harming the response in Africa as a result.

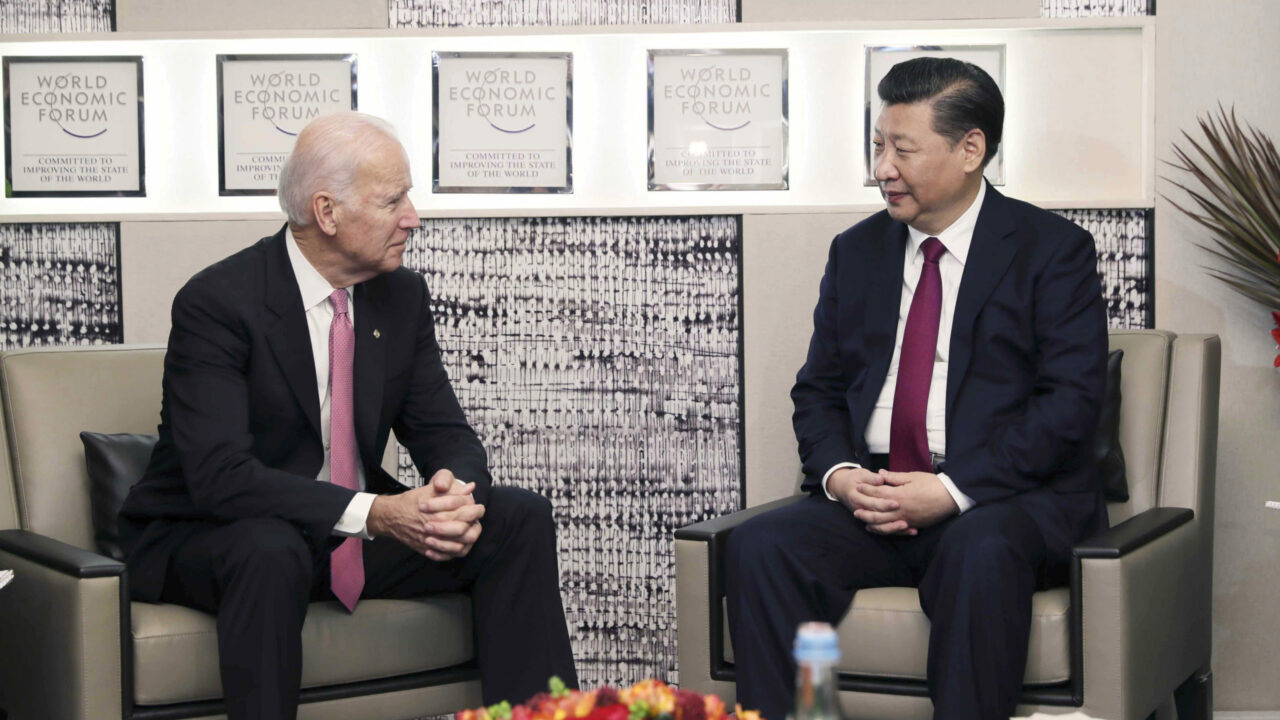

What might a President Biden do?

For either Donald Trump or Joe Biden, competition with China will feature prominently. The difference for Africa can be in the first order framing: Trump has chosen to compete head to head with China in Africa. A Biden administration may shift the approach to one less directly confrontational. This could relax the polarised perception around the economic sphere: the theme of this new iteration of great power competition. In reaction to this, it may be possible to avoid the traps of a bidding war and unintentional European partisanship. Should bipolarism retreat far enough into the background, Europe may even be able to cooperate with the US and China on a case-by-case basis without being forcibly conscribed to the one or other camp.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.