Protecting Europe from economic coercion: Strategy after the 2020 US election

Europe needs to enhance its toolbox for protection against economic coercion, carefully balancing its strategy in five areas

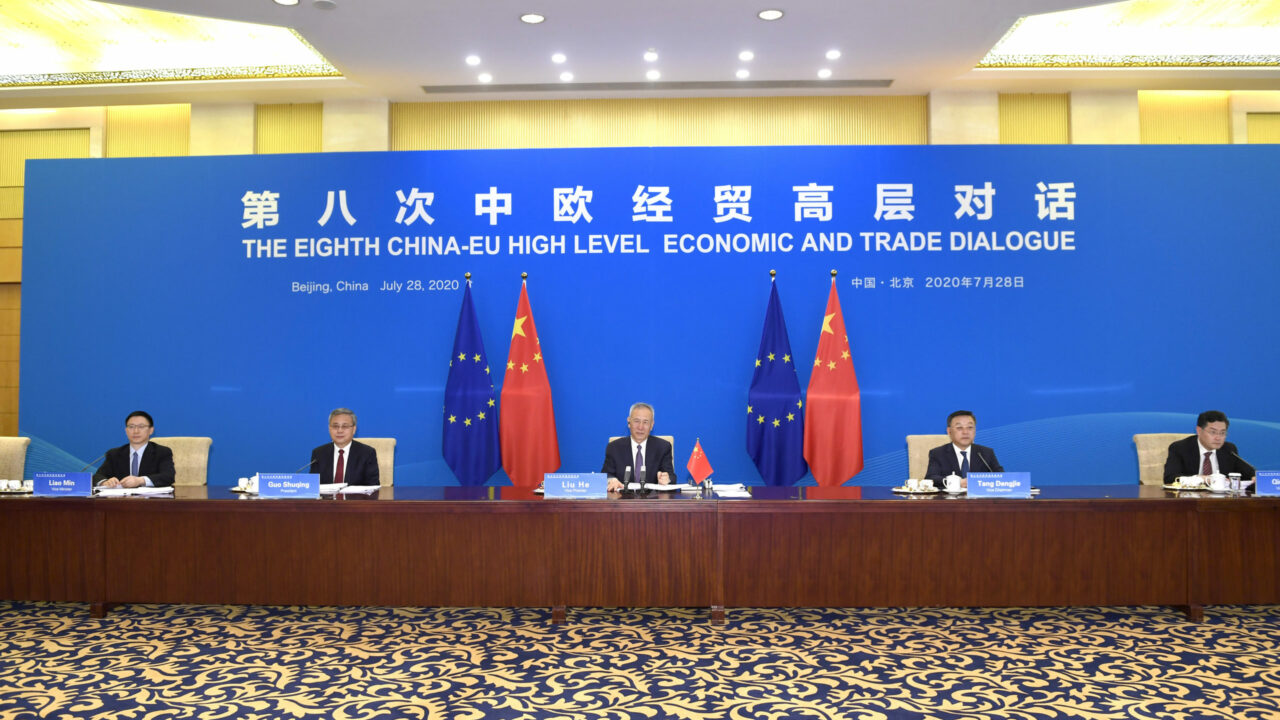

The geo-economic great power competition between China and the United States will continue to cause collateral damage to Europe in the coming years. The European Union is both on the periphery of, and a key battlefield in, the Sino-American clash. On the one hand, the two great powers’ strategic focus is on the Indo-Pacific – which means they do not always pay attention to events in Europe, and could damage European interests in the region. On the other hand, paradoxically, the European market is a key battlefield for China and the US. The EU has the only market of roughly equal size to the US and Chinese ones. It is central to many supply chains; home to some of the most globally connected economies and critical global infrastructure, such as the SWIFT financial messaging network; and a major market and huge source of valuable data for big tech companies – all areas in which Beijing and Washington compete.

Developments in China, the US, and various other countries – such as Russia – show that Europe needs to enhance its toolbox for protection against economic coercion (albeit in very different ways).

Threats from China

Europeans face a growing geo-economic threat from China. Beijing appears to be just getting started with its open threats to retaliate against countries that adopt policies it dislikes.

- Extraterritorial export controls: China’s new export control law could soon provide a formal legal basis for Beijing to massively interfere with European trade and to coerce European policymakers. From December 2020, the country will scrutinise end users of European exports to third countries and require foreign companies to trade in ways that China considers to be in its national interest – whatever this will soon mean in practice.

- Punitive tariffs: Beijing has threatened to impose punitive tariffs on German cars if Berlin excludes Huawei from contracts to build its 5G infrastructure. And Beijing has announced that Sweden’s recent decision to ban the company – which made it the latest EU member state to do so – will come at a great economic cost.

- Trade curbs: China’s recent actions against Australia show how far it is already willing to go on economic coercion. Canberra has called for an international inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus, has criticised Beijing for various human rights violations, and was the first country to ban Huawei from the construction of its 5G infrastructure. From the Chinese point of view, all these acts appear to be sanctionable behaviour. China has reacted with import curbs and de facto embargoes on Australian export products for which the Chinese market is crucial, ranging from wine and beef to cotton and lobsters. (For example, Australia exports 90 per cent of its lobster production to China and is the top wine exporter to China.)

China is in an increasingly strong position to exploit the power of its market for coercive purposes. In future, the country may be able to do so in a number of ways. For instance, it could use its highly attractive digital currency, which could give it a vast source of information on economic transactions and allow it to achieve its goals through threats of exclusion and forced data transfers.

The United States: Multilateralism and its limits

Europe can build effective protection from extraterritorial economic coercion while simultaneously becoming a better partner for the US under the incoming Biden administration. The administration recognises that Europe is, and will remain, the United States’ closest partner – and has a plan to re-engage with it. Europe should use this opportunity to rebuild as close a transatlantic relationship as possible, while concurrently increasing its resilience against possible US coercion when the sides’ policies do not align.

China is in an increasingly strong position to exploit the power of its market for coercive purposes.

Geo-economic tensions between the US and Europe will not simply disappear with the advent of a new administration. Congress, which is likely to remain under Republican control, remains key to adopting sanctions and other geo-economic policies. Economic measures are one of the key ways in which Congress can influence foreign policy. And some US economic measures that harm Europeans continue to have bipartisan support. The Biden administration will probably end most of the direct punitive measures against Europeans introduced by its predecessor, but it will sometimes weigh the costs of such action in domestic politics. Even the Biden administration will impose direct or indirect costs on Europeans if using a strategic instrument promises to have greater benefits than multilateralism would.

- Renew geo-economic transatlantic relations: It is in Europe’s interest to demonstrate to everyone in Washington that, for the US, a multilateral approach comes with greater benefits than a unilateral one. Wherever possible, Europeans could take decisive steps to reform the World Trade Organization (WTO) and other international institutions jointly with the US. Europe could also offer to conclude sectoral agreements with Washington to advance a positive agenda, reduce trade cost, and set common standards. It could do so without having to deal with the difficulties that come with comprehensive free-trade agreements, but while acting in full compliance with the WTO nonetheless. The EU already has negotiating mandates for an agreement with the US on the elimination of tariffs on industrial goods, and for an agreement on standards on technical conformity evaluation. Europe could strive for deals in these areas and try to quickly secure tangible results. It could also consider cooperation with the US in several substantive areas beyond market access regulation: professional recognition of qualifications, freedom of movement, and types of trade in services not covered by the WTO’s “essentially all trade” requirement for agreements.

- Offer a joint EU-US China strategy: Europe could offer to approach the geo-economic challenge posed by China jointly with the US, with a view to replacing unilateral US policies that cause collateral damage to the EU. Together, the EU and the US could demand equal conditions for competition, reciprocal market access, intellectual property protection, and state subsidies.

- Create a transatlantic working group on economic coercion: Recent years have shown that it is difficult to have a regular, constructive dialogue between transatlantic partners even on matters such as extraterritorial sanctions and export controls, punitive tariffs, and forced transfers of sensitive data. Europe should propose a joint working group with the US that includes sanctions coordinators and a range of other experts – with the aim of strengthening transatlantic relations now and in the future. This group could coordinate joint measures and help Europeans communicate their concerns about unilateral US measures to their American counterparts.

- Build strong instruments to protect Europe from economic coercion: Many of the measures in ECFR’s toolbox for protecting Europeans against economic coercion would make Europe a more attractive partner for the US (even if, at first, this may seem counterintuitive). The measures would help Europe become more capable geopolitically, especially vis-à-vis China – something that the US wants. Any US administration would take Europeans more seriously if they negotiated with Washington from a position of strength. And a stronger European partner makes the transatlantic couple more influential in the world.

- Create long-term resilience: The US has used extraterritorial measures against Europeans under various administrations, including over the trans-Siberian pipeline in 1982, with the Helms-Burton Act in 1996, and in several instances in recent years (such as on trade with Iran or the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court). For some time, both parties in Congress have favoured, or at least seemed fine with approving, sanctions that threaten European officials over Nord Stream 2. Trumpism will be around even after Joe Biden’s inauguration. Europe can expect to incur costs – indirect or otherwise – whenever a US administration profoundly disagrees with European policy.

Five key questions for Europe

Europe remains highly vulnerable to various forms of economic coercion, including extraterritorial measures. So long as this situation persists, Europeans may have to deal with more punitive tariffs, trade curbs, extraterritorial export controls, and forced transfers of sensitive data from China, the US, and others. This is why Europe needs to enhance its toolbox for protection against economic coercion, carefully balancing its strategy in five areas:

- Multilateralism and its limits. Other powers will take unilateral strategic action when this promises them greater benefits. Europeans should respond by doubling down on multilateralism. But they cannot promote multilateralism from a position of weakness. Sometimes, Europe will need to act more unilaterally, bilaterally, or plurilaterally.

- The costs of inaction and reaction. To determine what course of action to take in a specific situation, Europeans need to weigh these two types of cost. Inaction is often more damaging than they suspect, as it may become more costly to use a certain instrument further down the road.

- Resilience and retaliation. ECFR’s toolbox includes resilience measures that decrease the impact of economic coercion on Europeans, and retaliatory measures that disincentivise the use of economic coercion. One will not work without the other. Europe needs the right balance of both, along with a credible set of instruments.

- Deterrence and free trade. Heavy-handed use of European countermeasures would threaten liberal, rules-based trade – but so would inaction and ineffective policy responses, because they invite more economic coercion. The right kind of countermeasures will keep markets open.

- EU unity and effectiveness. The EU cannot sacrifice effective protection from coercion because it strives for absolute unity. But it cannot accept ever-increasing EU divisions in an absolute quest for effective responses either. ECFR’s toolbox provides ways to reconcile the two considerations.

This paper is a product of the European Council Foreign Relations’ work and the opinions expressed in it those of the individual authors. The paper is based on a systematic consultation exercise that engaged with high-level public and private actors, mainly those from Germany and France.

ECFR’s Task Force for Protecting Europe from Economic Coercion worked on the toolbox and this paper during 2020. Members of the task force discussed a range of possible responses to extraterritorial coercion and grave violations of sovereignty through economic measures. The papers do not reflect a consensus of the task force. The authors of the papers took into account how participants from diverse backgrounds in the public, economic, and financial sectors, and academia, collectively viewed opportunities and challenges on each instrument.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.