Operation reciprocity: France’s evolving relationship with Africa

A lighter military footprint for France in Africa will reveal the true depth of its relations with the continent – and could provide a model for the broader European approach

In 2017, the French president Emmanuel Macron caused a stir with his speech to an audience of university students in Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou. To a smattering of heckles, he called for a break with the past in France-Africa relations and an end to opaque French ties with African governments. Instead, Macron advocated a new approach, based on reciprocity and stronger connections with civil societies: “I am from a generation that doesn’t come to tell Africans what to do,” he said.

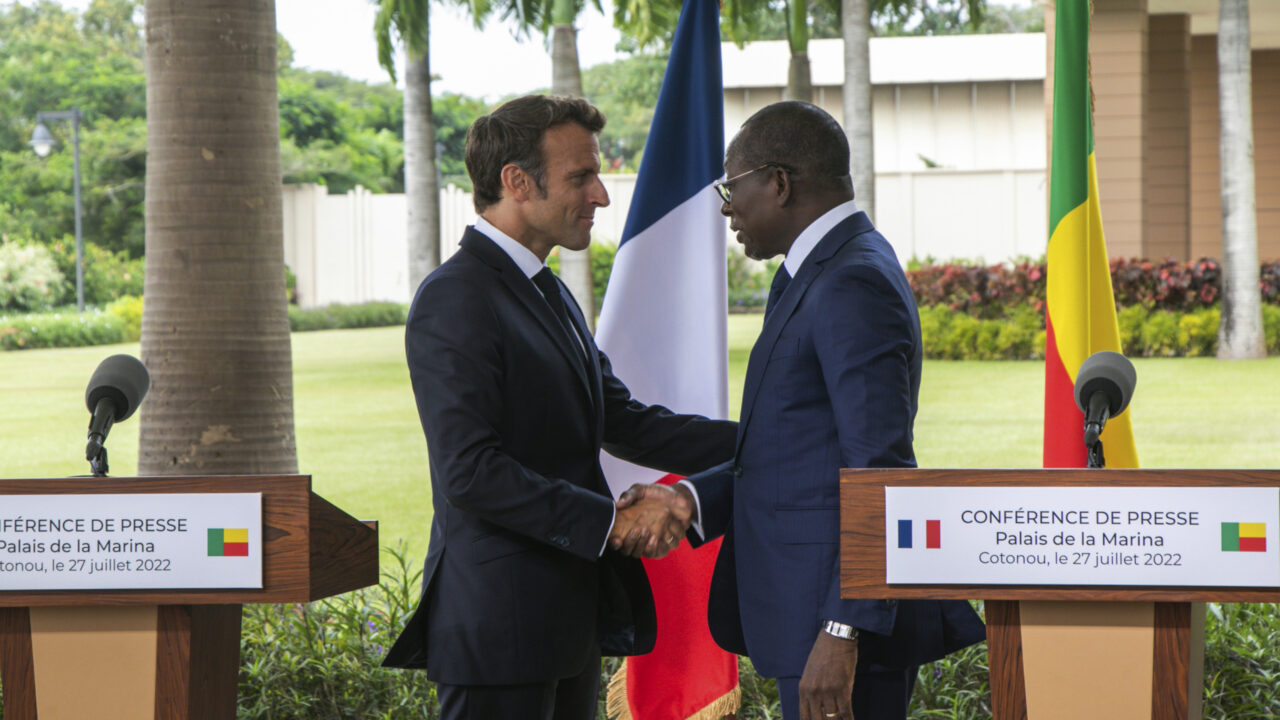

This year, Macron extended that logic in a speech on the eve of his visit in March to central Africa, in which he reiterated his intention to build a “new, balanced, reciprocal, and responsible relationship” with the continent. This would involve a partnership approach to African economies and more dialogue with African societies. Importantly, in the context of France’s decision to end its flagship counter-terror campaign in the Sahel – Operation Barkhane – late last year, it would also involve a lighter footprint in France’s military presence on the continent.

Macron set out how France would aim to ‘Africanise’ French military bases (except its Djibouti base, which is focused on Indo-Pacific strategy), through co-management and an adaptable French response to African partners’ needs. If France follows through on this, although ‘hard power’ support will remain, the country will no longer be on the front line in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel, after unwillingly assuming, as Macron put it, “exorbitant responsibilities” and struggling to extricate itself from the internal political dynamics of its African partners.

Macron made clear that he wants this approach also to provide a model for broader Europe-Africa relations, given increasing awareness among Europeans of Africa’s importance in tackling global challenges. Deep-seated views among European (and African) partners about French intentions in Africa may be difficult to change. But doing so will become more likely through a coordinated and Europeanised approach – in matters of security and beyond.

The bedrock of France-Africa relations

One crucial benefit from such a change in approach is that a refocus away from security should reveal the true depth and multifaceted nature of the France-Africa relationship.

In recent years, France has begun to build goodwill and face its colonial past in Algeria, Rwanda, and Cameroon through, notably, the establishment of historical commissions. It also passed an act of parliament on the restitution of cultural goods to Benin and Senegal. In his speech, Macron expressed a desire for new draft legislation to strengthen this policy, as well as a pan-European dynamic in initiatives in this area – for instance, through a new Franco-German fund on provenance research.

This politics of memory – while urgent and necessary – is just one part of a broader dialogue between societies and people from France and Africa

Yet, this politics of memory – while urgent and necessary – is just one part of a broader dialogue between societies and people from France and Africa. Some commentators have succumbed to the temptation of viewing the relationship and all its facets through a postcolonial lens. Yet, a wider-ranging dialogue between French and African societies, especially among younger people, represents an opportunity to face the past while also moving beyond this reading.

France hosts the largest African diaspora in Europe and 14 per cent of French emigrants live in Africa. Africa is home to the largest number of French speakers in the world. French and African societies and cultures are in constant exchange, with various African artists exhibiting and producing their work in France. Recent data show that a growing number of Africans study in France, which remains the leading destination worldwide for students from sub-Saharan Africa. This is underpinned by strong university and scientific cooperation. Economic ties between France and Africa are also diverse, and there is a growing presence in Africa of French start-ups in many innovative fields, particularly in the digital and energy transitions.

Macron addressed this great potential in his speech, announcing further support for African entrepreneurship and diaspora projects andmore “solidarity and partnership-based” investments. To build on this, in June France will host the “Summit for a New Global Financial Pact”, co-steered with India. The summit could result in a boost in innovative financing by rich countries for those states most affected by climate change, which could also improve those countries’ budget capacities and reduce their debt burdens. Furthermore, on his central Africa trip, Macron highlighted environmental protection in Gabon, agriculture in Angola, and culture in Brazzaville and Kinshasa. This can all contribute to a genuinely reciprocal, demanding, and ambitious partnership with Africa.

The ‘more Europe’ challenge

France has expressed a desire over some years for other EU member states to get more involved in Africa, for example through the Takuba task force in the Sahel and more recently “Team Europe” – coordinated initiatives between member states and EU institutions – trips to Ethiopia, Niger, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Despite genuine French efforts at coordination, some policymakers from other capitals express in private a perception that France looks after its own interests in Africa, and then seeks partners to burden-share – acting as a team user rather than a team player. Right or wrong, this view could prove an obstacle for Macron.

French leaders will need to convince their European partners to operationalise the new approach in a collective way. This implies finding ways to shift from a leadership position to that of a facilitator. Paris will need to use its network to better connect European and African partners. If authorities in Africa so wish, this should also involve ‘Europeanising’ military bases in the medium term, on their way to true Africanisation.

The EU and member states, for their part, need to acknowledge the benefits of a strategic approach to Africa, be more politically present in high-level Team Europe trips to the continent, and increase their efforts to provide military, logistics, and healthcare support, after years of relying on France to do the heavy lifting on security.

Europeans should also demonstrate to African partners that support for Ukraine does not come at the expense of their partnerships with Africa. They need to better mobilise their defence and technology industries and the European Peace Facility (EPF) to provide assistance measures to African armies. Niger, for instance, can be a ‘laboratory’ for renewed European action: the EU is trialling a new partnership mission combined with EPF support, increased bilateral support from several member states, and importantly, a Niger lead on operations. The countries of the Gulf of Guinea will be the next test. Security challenges there are increasing and African partners are requesting assistance, yet the European appetite currently appears limited.

One year after the EU-African Union summit, Europeans are facing a more fragmented world. It is urgent that they revive and deepen the Europe-Africa partnership to meet common challenges. The EU and its member states should take Macron at his word on the need to act collectively and position Europe as the reference partner on defence and security issues, as well as the financing of infrastructure in Africa with the implementation of the Global Gateway. This represents an opportunity for the EU, France, and other European countries to build a renewed partnership with Africa, based on shared interests and responsibilities, that can genuinely address their numerous common challenges.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.