Line of argument: Why Berlin and Washington should compromise on Nord Stream 2

Berlin and Washington need to avoid a worst-case scenario in which cooperation on other pressing transatlantic issues becomes impossible

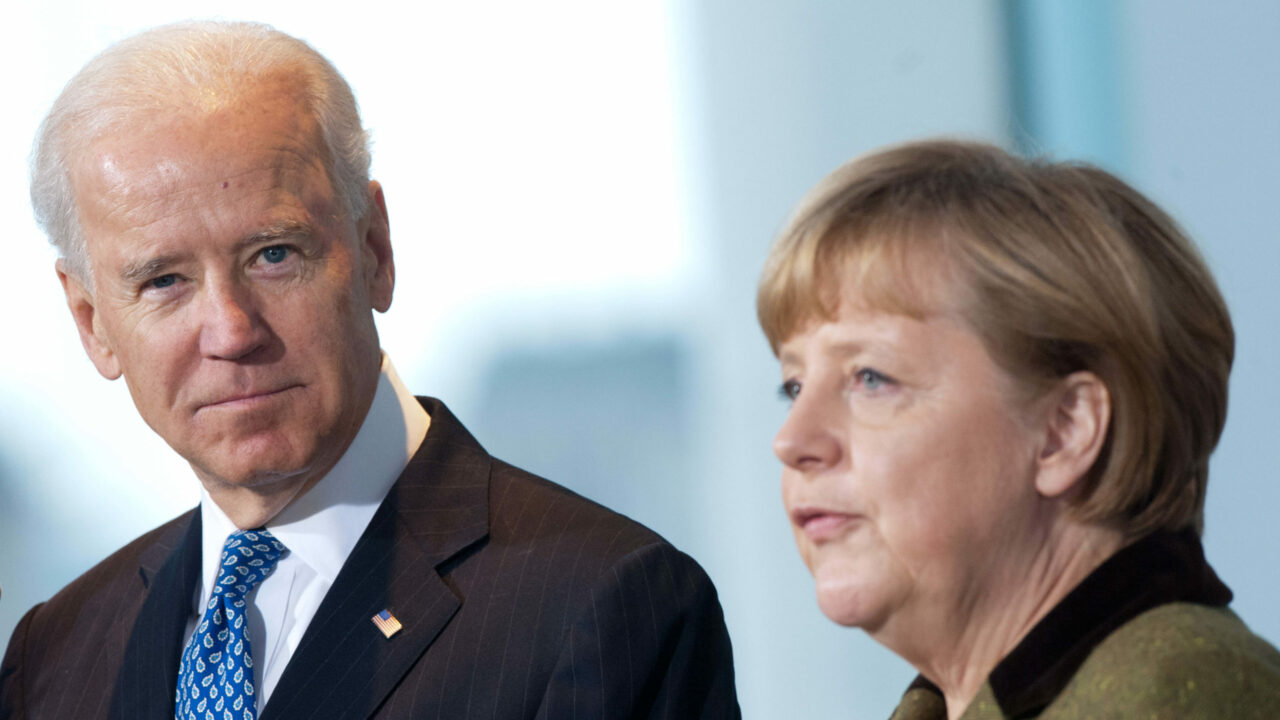

After four years of chaos in US-EU relations, it was as if the clouds immediately parted on 3 November 2020. Transatlanticists in Washington and across Europe breathed a sigh of relief as Americans voted for a president who is both pro-EU and pro-NATO. The work of repairing a damaged transatlantic relationship could finally begin. Unfortunately, that honeymoon period may be coming to an abrupt halt. Progress on several pressing transatlantic issues in the next four years will depend on deep coordination and healthy relations between the United States and Germany. That bilateral relationship is on thin ice. At the top of the list of irritants is the Nord Stream 2 pipeline in the Baltic Sea, which is around 95 per cent complete and is set to provide Russian natural gas to the European market.

To an outside observer, a pipeline project years in the making might not seem like it has the ability to derail the US-European partnership. That assumption is wrong; this single initiative is a proxy for a whole spectrum of US concerns about Europe. This is why successive US administrations have strongly opposed it. American policymakers fret about growing Russian influence across Europe, the potential for Ukraine to lose billions in annual revenue from transit fees if Russia tries to bypass its natural gas infrastructure, and the reality that Washington may have less say on European policy as the continent becomes more independent-minded. They are also aware that, as ECFR’s latest EU Coalition Explorer shows, Germany is the key country among the EU27 when it comes to European cooperation on transatlantic relations and energy policy.

Germans, for their part, see Nord Stream 2 as strengthening European energy security, and believe that US hawkishness on Russia is counterproductive. In the long run, they view clear-eyed and cautious engagement with Moscow as the smarter play.

Regardless of who is right, the current stand-off is leading to an outcome in which everyone loses. American policymakers need to accept that Germany is very likely to complete Nord Stream 2, while German policymakers need to concede that some American concerns are valid and come to the table with serious options to make the project palatable. The US and Germany will not find it easy to achieve a compromise, but they must do so before the broader transatlantic relationship sustains lasting damage.

Today, US policy on Nord Stream 2 policy is largely dictated by a bipartisan group of US lawmakers led by Texas Senator Ted Cruz. They are demanding that the government impose sanctions on all companies involved in the project, eventually including German ones. For this group of lawmakers, especially Cruz, the US response to Nord Stream 2 boils down to one aim: being tough on Russia. The Biden administration has made it abundantly clear that it also believes the pipeline is a bad deal for Europe. Indeed, Politico recently reported that the Biden team is vetting a former State Department official, Amos Hochstein, for appointment as a special envoy “to lead negotiations on halting the construction of [the pipeline]”.

Even so, the administration would prefer a less confrontational approach. And it is hard to see how this appointment is not the Biden’s team response to growing pressure from Congress. The senators said that they would block congressional approval of two nominees for high-level posts in the administration – Bill Burns as CIA director, and Brian McKeon as deputy secretary of state for management and resources – unless Secretary of State Antony Blinken issued a “strong declaration” hinting at future sanctions. Though they relented after Blinken made what they felt was an appropriately tough statement, tensions remain high on Capitol Hill.

It would be unwise for German leaders to assume that, if they simply wait long enough, the US will relent.

Last week, the Biden administration announced a sweeping set of sanctions on Russia in response to the country’s involvement in the SolarWinds cyber attack, interference in the 2020 elections, and ongoing occupation of Crimea. Conspicuously absent from the measures were Nord Stream 2 sanctions.

This is not a bad thing, because it gives the US a chance to try strategies other than the threat of sanctions. Several strategists have laid out other potential solutions to the impasse, which the administration should immediately consider. The first and most attractive option should be the “emergency brake” mechanism, which could halt energy flows through Nord Stream 2 pipeline if Russia violated the agreement to keep using Ukraine’s gas transit infrastructure. Other options include addressing central and eastern European countries’ concerns by investing in their energy infrastructure, and by launching discussions between the US and European countries – perhaps including Ukraine – on the future of energy trade with Russia. Yet another option is to allow the completion of the pipeline, but to postpone its operation until after Russia comes to the table with some of its own concessions. (This approach would be relatively difficult to take given the need to then link Nord Stream 2 to broader political disputes between Russia, Europe, and the US.)

The big question is: what happens next? Germany, for its part, has not made it easy for anyone. As political scientist Constanze Stelzenmüller recently wrote for the Financial Times: “Berlin’s mulish inflexibility could alienate the most Europe-friendly American administration it is likely to see in a generation.” Some recent reports suggest that Berlin has come to the table with concessions intended to persuade Washington to back off, including “trade deals and increased investments in green energy projects in Europe and Ukraine”. But the details of those offers remain unclear. At the same time, people involved in the discussions on Hochstein’s potential mandate say that his initial role will be to “impede the pipeline without alienating a key US ally.” That seems like a daunting task, especially when US opposition to the pipeline is playing out so publicly.

However, it would be unwise for German leaders to assume that, if they simply wait long enough, the US will relent. Their assumption should be that Congress will keep turning the screw on the Biden administration until the latter has no choice but to implement sanctions that eventually target German companies. At that point, it will be too late: Germany will have lost its leverage in the negotiations. And, if the Biden administration implements and then removes sanctions, it will be seen as weak on Russia. Both sides will have lost.

Germany needs to come to the table now with serious ideas for a way forward. The worst-case scenario is one in which the US implements sanctions on German companies, Germany completes the pipeline anyway, and cooperation on other pressing transatlantic issues becomes impossible as a result.

I wrote for the Heinrich Böll Stiftung in March 2020 that the US and Europe need to transcend their old relationship grounded mainly in collective security and NATO. The transatlantic partners must re-orientate and broaden their partnership around a stronger relationship focused on climate, a joint approach to China, technology policy, and human rights. I had no illusions that this would be easy, but I am surprised by how quickly the situation has deteriorated. Nord Stream 2 poses a serious problem that Washington and Berlin need to solve as soon as possible.

Rachel Rizzo is director of programs at the Truman Center for National Policy and the Truman Project. She is also an adjunct fellow at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), working in the Transatlantic Security Program.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.