How Britain and the EU could cooperate on defence after Brexit

The UK will have to decide how involved it wants to be in EU defence efforts. It seems likely that the country’s aim will be to have flexible structures that allow it to plug into European foreign and defence policy where doing so is in its interests

In November, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson made headlines when he announced that the Ministry of Defence would receive an extra £16.5 billion over four years on top of its annual budget, set at £41.5 billion for 2020. This is the biggest British defence investment since the end of the cold war. The decision was particularly noteworthy because it came on the back of the chancellor’s decision to cancel the planned comprehensive spending review in light of the covid-19 pandemic, and to award all government departments only a one-year funding deal instead. The prime minister said that he had decided to give the Ministry of Defence an exemption to “end the era of retreat”.

Defence cooperation is one of many areas in which, facing an uncertain future due to Brexit, the United Kingdom will need to reorder its relationship with the European Union. On the one hand, the challenge appears surmountable: the EU is not a classic defence alliance, the UK is a credible military actor in its own right, and the country will remain in various bilateral and multilateral alliances with EU member states – most notably NATO, but also the Joint Expeditionary Force (which includes EU member states Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Sweden, as well as non-EU state Norway) and the Combined Joint Expeditionary Force with France. Also, Brexit does not change the UK’s geographic position – the country and EU member states will continue to live in the same strategic environment. They have many of the same fundamental interests due to both this shared environment and their common values and ideas.

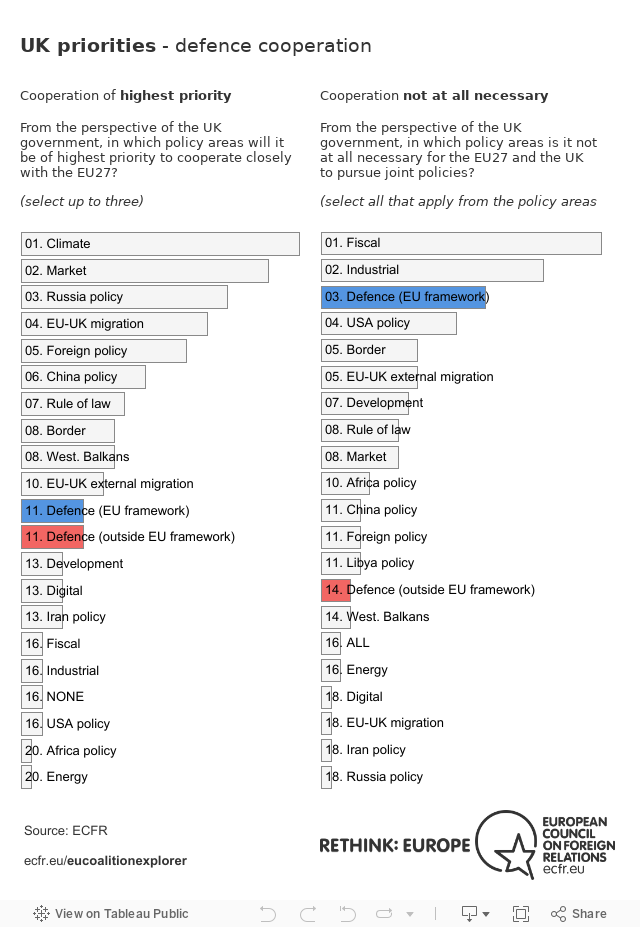

This context may explain why many British policy experts do not seem to feel an urgent need to figure out the future EU-UK relationship on defence. When the European Council on Foreign Relations polled these experts earlier this year, defence was not high on their list of priorities for close cooperation with the EU. In the list of 20 policy areas in which the UK government is likely to believe that “it will be of highest priority to cooperate closely with the EU27”, defence ranked in 11th place. However, when asked about working with EU countries on defence more broadly (outside EU structures), most respondents stated that the UK government had an interest in doing so.

Unlike most areas affected by Brexit, defence cooperation is an issue on which the biggest problem the UK has to deal with when working alongside the EU was primarily caused by its departure from the bloc. For decades, EU ambitions and efforts in common defence were relatively subdued. But, since the Brexit referendum, the EU has put out an impressive array of projects and programmes, from Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) to the European Defence Fund, to the more lofty goals of European strategic autonomy. The EU’s new budget, the Multiannual Financial Framework, is the first to include a section on defence. Brexit made this possible by removing a heavyweight opponent of such efforts. It also created the impetus for these initiatives, as – together with the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States – it reminded Europeans that the world was changing, and that Europe needed to prepare for the challenges this would create.

The UK will have to decide how involved it wants to be in these and other EU efforts. It seems likely that the UK’s aim will be to have flexible structures that allow it to plug into European foreign and defence policy where doing so is in its interests. In particular, the creation of a European Security Council, or the further empowerment of the E3 format (with France and Germany), might be a good way for the UK to retain influence on European foreign and security policy. The EU recently established the general conditions in which non-EU countries could receive an exceptional invite to participate in individual PESCO projects. Such participation requires unanimous support from the project’s members.

British firms have an economic interest in being involved in such projects. And it may make strategic and financial sense for the UK military to play a part in the development of at least some big-ticket military items (for instance, it is conceivable that the Future Combat Air System, a Franco-German-Spanish fighter jet project, could combine with the British-Italian Tempest). It seems likely that the UK would want to ensure that it had some power to shape these projects. Hence, the UK needs EU member states either to make the argument that it should be included, or to speak for it and articulate British views (much in the same way as some member states used to have the UK speak for them in the past). Who could these partners be?

According to the experts ECFR polled, the UK sees the two EU heavyweights, France and Germany, as the most essential partners on defence questions, followed by Italy and the Netherlands sharing third place, and Poland and Romania sharing fourth place. But this assessment isn’t blue-eyed, as the counter-question reveals: according to the same experts, France is not only the UK’s closest partner on defence matters, but also comes first among the countries that British researchers consider to be “most strongly [opposed to] the UK government’s positions”.

This seems to be an accurate assessment. One the one hand, the UK and France have very strong defence links and a history of cooperation ranging from Saint-Malo to Lancaster House. And French President Emmanuel Macron has called for more inclusive European defence projects and concepts that would include the UK, such as the European Intervention Initiative and the European Security Council respectively. On the other hand, under Macron, France remains far more focused on defence questions than any other country in the EU, and the most vocal supporter of European strategic autonomy – the guiding idea of which is to make the bloc a more strategic and militarily capable actor in its own right. Thus, France is an important point of contact for the UK.

When it is seeking supporters in the EU, the UK would be well-advised to look beyond the big countries.

Still, when it is seeking supporters in the EU, the UK would be well-advised to look beyond the big countries. ECFR’s Coalition Explorer identifies the states whose governments most strongly support working on defence questions outside a strict EU-level framework. If the UK wanted to capitalise on such sentiments, good partners within the EU would be: Lithuania, where 48 per cent of experts argue that their government would prefer to deal with defence questions outside an EU framework, Estonia (42 per cent), Poland (42 per cent), and Denmark (40 per cent). However, Poland is the only one of these four states that British experts name as an essential partner for defence cooperation. More generally, the UK may want to work with EU countries that have concerns about EU defence efforts undermining NATO – especially eastern European ones – or that see these efforts as merely instruments to help western European companies increase their market share.

In the end, the biggest problem for the UK is likely to come in the form of European strategic sovereignty. Strategic sovereignty (or autonomy) remains a contested and controversial topic within the EU, but it gives the bloc something to aspire to. And, while few would define it as a project that is exclusive to the EU, it seems likely that the UK will never play a defining role in it. This will probably weaken the UK’s impact on all European foreign and security policy decisions and projects.

This essay is part of a series of commentaries on the EU Coalition Explorer UK Special. Two other commentaries discuss the potential for UK-EU cooperation on climate and trade policy.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.