Germany at the helm: Can it bring Europe together in 2020?

The German presidency offers the chance to build on strong levels of structural cohesion between member states – but citizens remain sceptical on some fronts.

Next July, the European Union’s largest member state will take on the crucial role of president of the European Council. Pro-European governments and citizens across the continent will have high expectations for stronger integration under German stewardship. But how likely is this to transpire?

One crucial factor is clear: Germany’s ability to steer the EU forward will depend on the readiness of the member states to cooperate with one another, despite their many differences. ECFR’s EU Cohesion Monitor, released in April this year, can help us consider how amenable they are likely to be to this. Since 2007, the Cohesion Monitor has measured the degree of cohesion among the 28 EU members by looking at a number of indicators of willingness to cooperate. These include a cluster of measures of citizens’ experiences, attitudes, and expectations; and a structural cluster covering the degree of integration at the macro-level (such as trade relations, EU funding, single market transposition, a country’s number of opt-outs, and multinational military deployments).

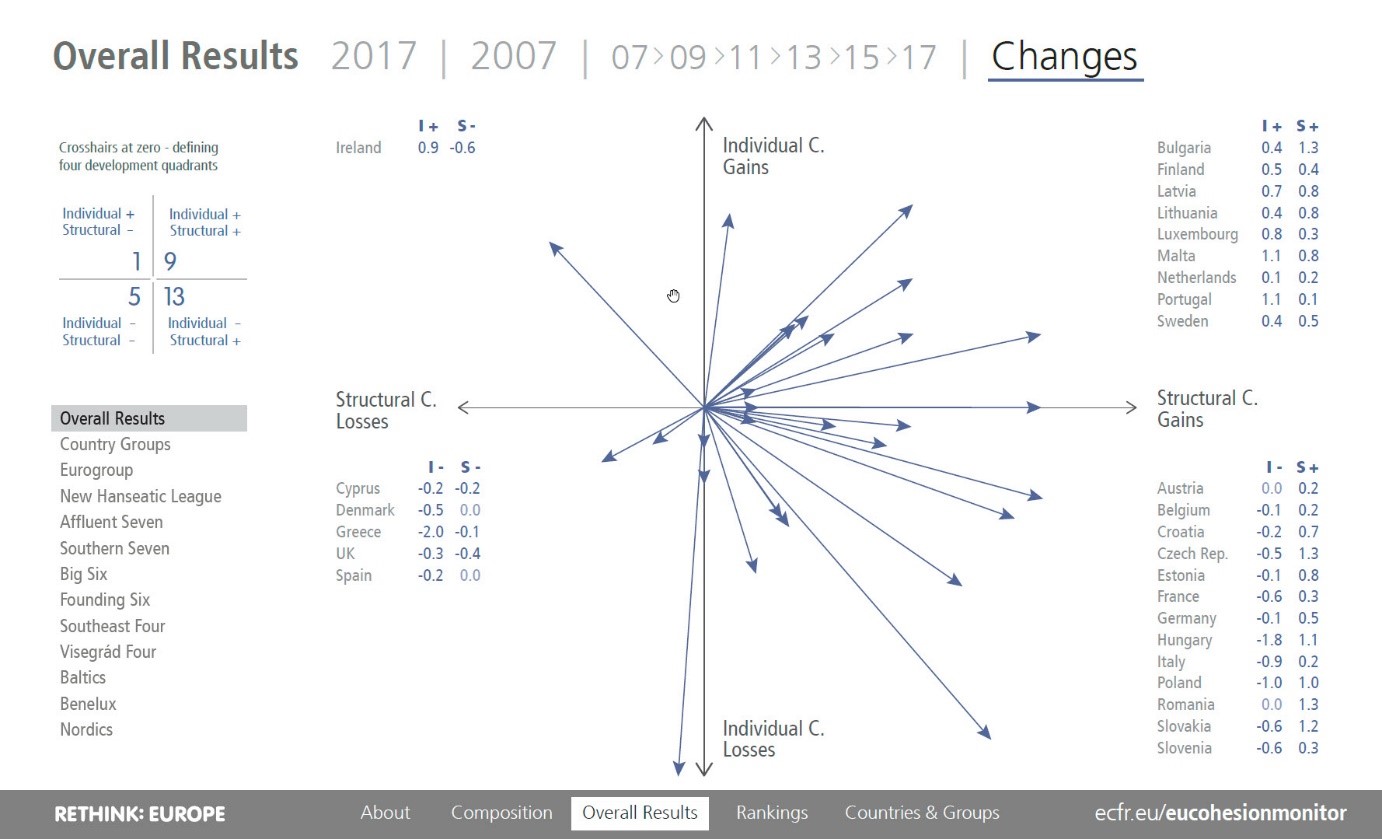

The story of cohesion in the EU between 2007 and 2017 gives cause for hope: levels of cohesion are overall as strong as they were in 2007 – the year before the financial crisis – with nine countries more cohesive in both the individual and structural clusters. Central and Eastern European states have made big gains in structural cohesion, while cohesion in the Baltic states is particularly strong at both structural and individual level.

However, the results for individual cohesion are more mixed overall: in older member states, such as Italy and France, individual cohesion has declined considerably since 2007. This is likely due to the successful campaigning of Eurosceptic and anti-EU parties. The German presidency will need to take this volatility seriously: more European integration is unlikely to take place without a citizenry that actively associates the EU with positive attitudes and experiences.

First and foremost, how to combat forces that risk pulling EU states away from each other? Recent official announcements suggest that Germany is actively looking for new ways to strengthen cooperation within Europe. One major intervention in this regard was the recent ambassadors’ conference at which the German foreign minister, Heiko Maas, emphasised the importance of “hold[ing] Europe’s middle ground together”. The crucial Franco-German relationship aide, he argued, new formats of cooperation are likely to be decisive for advancing European integration. After Brexit, countries like Spain, Italy, and Poland will have to take on more responsibility, and the EU as a whole will need to improve its means of consulting member states, by involving them more, and ensuring that countries such as the Baltic states are heard.

Maas went on to say that Germany is willing to be proactive as a broker between east and west within the context of the Three Seas Initiative: he recognised that the stated aim of the initiative was originally to foster cooperation between central and eastern European states. But it is likely that Germany and others saw in it an attempt to hinder European cooperation. He also underlined the importance of the peer review mechanism for the protection of the rule of law that the EU recently agreed, which would come into effect during the German presidency. The foreign minister further promised that, on the divisive issue of migration, voluntary ad hoc measures should be established to take in refugees and to alleviate the pressure on countries like Italy. His statements show that Berlin is aware of the centrifugal forces threatening the European project – but it is difficult to tell how realistic achieving this ambitious agenda will be.

Secondly, how to prevent funding becoming a threat to EU cohesion? The agreement on the EU Multiannual Financial Framework for the seven years from 2021 – and hence the delicate negotiations between the ‘net payers’ into the EU budget and the recipients – is also set to take place during the second half of 2020. A durable and functioning redistribution of funds has always been an existential question for the EU, with the United Kingdom being one of 11 net contributors. Indeed, its €6.9 billion share in 2018 meant that the UK was the second biggest contributor to the EU budget after Germany. As the UK leaves, however, the coalition of net payers will change decisively, and the distribution of funds will require significant renegotiation, which could pose risks to EU cohesion. Even though the German coalition government has committed itself to contribute more to the EU budget in the interests of economic stabilisation and structural reforms within the eurozone, it remains to be seen how much of the UK’s old share Germany and the other net contributors will be willing to take up, or whether other countries that have so far been recipients will also have to pay more in future.

Thirdly, should Germany press for further economic and monetary union? This question is likely to be the least problematic, as the EU Cohesion Monitor shows that the presidency should be able to build upon broad public support for fostering EMU: about two-thirds of European citizens are positive towards this. However, the German presidency will still need to take note of the fact that, in many places, popular scepticism of EMU has risen, especially outside the eurozone. Between 2007 and 2017, approval of EMU rose in ten states, while in 15 member states it decreased – notably, in all nine member states outside the eurozone. Eight of these showed the strongest falls in approval. This suggests that further integration in the future could in fact end up widening the gap between eurozone ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’, potentially creating new obstacles for later EMU enlargements. On the other hand, the situation appears positive when looking at the structural base for more economic integration, such as the development of economic ties among EU members: trade relations have become more intense overall (with a clear increase in 15 states, and only a very slight decrease in most other member states). Furthermore, there has been an increase in transposition of EU legislation, as well as a decrease in single market infringement procedures.

Fourthly, how can Europe be more cohesive on China policy? Precious time has passed since China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its enhanced cooperation with central and eastern Europe (institutionalised as the ‘17+1’) have allowed the country to enter Europe by the back door. China has even recently established a new system of international commercial courts, providing it with a new way of increasing its trading partners’ dependency. The Chinese reading of human rights and democracy – including Beijing’s reaction to the latest Hong Kong protests, re-education camps in Xinjiang, and a social credit scoring system – not only contradicts European interests, but touches upon the very values that the EU has declared to defend. And yet, while the German government has been preparing an EU-China summit for September 2020 in Leipzig – at which the EU should ideally speak with one voice – it is also clear that the biggest companies in one of the leading exporting nations rely heavily on good business relations with China, which is Germany’s third biggest trading partner in exports after the United States and France. On her visit to Beijing last month, Angela Merkel was accompanied by the CEOs of 25 of Germany’s biggest companies, ten of which were even able to fly with her in her plane. Other member states are well aware of this high degree of dependency and this, in turn, raises the question of how credible Germany can be when acting as a broker of a ‘common’ European position towards China.

Finally, what about the long-term goal of a cohesive European foreign and defence policy? These most delicate of fields of cooperation touch upon the very core of national sovereignty, and so remain highly contested. It is not obvious where common ground might immediately be found: even the founding EU member states have long had very different approaches from one another. Nevertheless, at the ambassadors’ conference, Maas formulated ambitious steps towards Germany’s vision of a strong and, as he calls it, “sovereign Europe”, including qualified majority voting for EU foreign policy decisions and a more coordinated appearance for the EU in multilateral settings. In his view, the EU should engage in all pressing international issues, intensify its relations with Russia, work towards a rapprochement with Iran, increase its cooperation with the African Union, and strengthen its ties to Latin America through the EU-Mercosur treaty. Germany should also engage more deeply on forging a common European defence and security, including by making the common defence fund fully operational by 2021 and by improving civil crisis prevention through the establishment of a Berlin-based European competence centre.

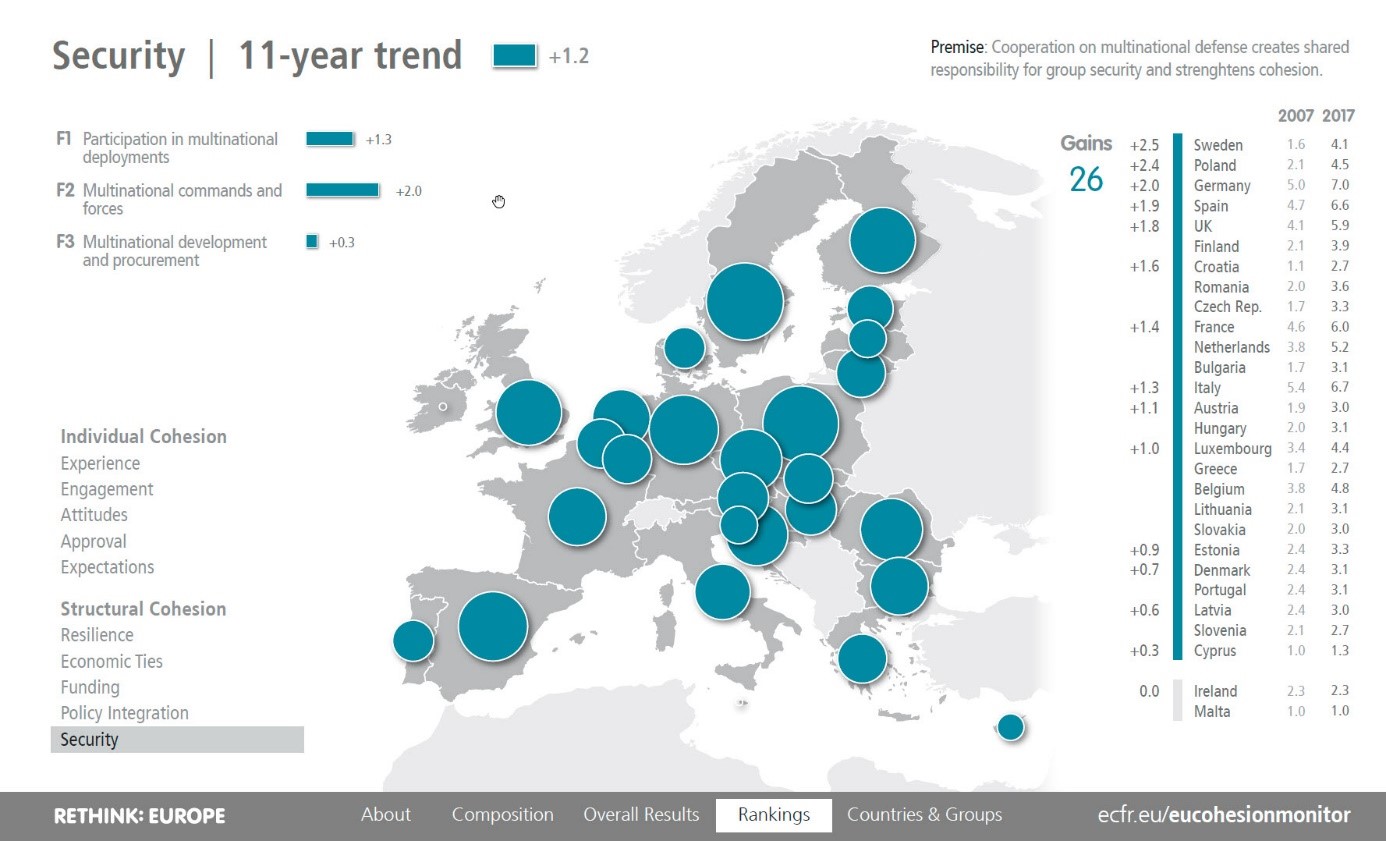

How much progress can the EU make towards these ambitious goals under next year’s German presidency? Overall, the EU Cohesion Monitor confirms that the EU is much less integrated on foreign policy matters than it is on EMU. However, all three of the Monitor’s structural indicators – participation in multinational deployments, multinational commands and forces, and multinational development and procurement – saw an increase in cooperation (+1.2 on a scale from 1 to 7) in 26 of the 28 member states between 2007 and 2017, with only Ireland and Malta remaining unchanged.

The picture looks a little different when examining citizens’ support for a common foreign policy – which has seen rises in support in eight countries, but falls in 19 – or a common defence and security policy (nine rises and 17 falls). Despite this, approval remains high overall, with around three-quarters in favour of a common European defence. Likewise, other surveys also show that people want the EU to take a clearer stance on tricky international issues, be it China or Russia, Iran or Syria, and that they believe the United States alone can no longer guarantee European security. So, Germany will be able to build on the progress already made at the structural level, but EU citizens still need persuading that concerted action on pressing international issues will be impossible without common decision-making structures.

The German presidency will be followed by Portugal, Slovenia and France, which could provide continuity towards more integration.

Despite all those challenges, there are only a few other countries in the EU with similar political weight and capacities at their disposal to Germany. On the one hand, the hopes and expectations set for the German presidency are justified, not least because a pro-European government in Germany will be later followed by the presidencies of Portugal, Slovenia, and France, all of which are ‘pro-European’. This could guarantee a period of continuity in integration. On the other hand, even the most EU-friendly governments may consider some national interests vital enough to block common European solutions. This includes China policy, but also areas in which Germany has thus far appeared far less ambitious than many of its European partners had hoped, such as tackling climate change or finding a balanced and sustainable European migration policy to replace the unfair Dublin agreements. And, even though Merkel’s Social Democratic coalition partner has stressed the urgency of moving towards a more social Europe, it is hard to believe that Germany’s period in charge will see it do much on this front: the chancellor’s Christian Democratic Party has already expressed its reservations about this. Germany’s presidency could thus end up performing well at declaratory and administrative level – but falling short of concrete achievements.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.