Gangster governance: How Slovakia fought back against corruption

The events surrounding Slovakia’s parliamentary election show how endemic corruption can lead to unpredictable political transitions.

Public anger at targeted killings and state-backed corruption has brought down the leaders of two EU governments since the start of the year. Europe’s most powerful politicians may rarely pay attention to events in Slovakia or Malta, but they would be wise to watch the aftermath of the political transitions that have occurred there. The groundswell of discontent in the countries suggests that, when enough citizens come to believe that the state is mired in graft, this can abruptly transform national politics. And it can even have geopolitical implications. After all, the “European sovereignty” sought by leaders such as French President Emmanuel Macron is only so good as the governments it empowers.

Slovakia’s parliamentary election, held on 29 February, resulted in a victory for Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OLaNO), a centre-right party under which “zero tolerance of corruption will be the alpha and omega” – according to its leader, Igor Matovic. Like President Zuzana Caputová, who was elected to the largely ceremonial post last year as the representative of Progressive Slovakia, Matovic campaigned on a promise to dismantle the corruption network allegedly responsible for the murder of investigative journalist Jan Kuciák and his fiancée, Martina Kusnirová, in February 2018. Matovic’s uniquely single-minded focus on graft may explain why OLaNO rose from around 5-6 percent in the polls in December to claim 25 percent of the vote. In any case, the parliamentary election ended the long rule of Direction–Social Democracy (SMER) and its autocratic leader, Robert Fico.

A similar fate befell Malta’s Joseph Muscat, who eventually resigned as prime minister in January, under intense pressure from Maltese voters and the European Union over his response to the October 2017 assassination of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia. Muscat’s Labour Party remains in power – just as SMER did after large-scale protests forced Fico to resign as prime minister in March 2018. Although Muscat no longer leads his party, it is unclear whether he will have the kind of informal control Fico retained after leaving the prime minister’s office.

Fico was doomed partly by his alleged links to Marian Kocner, a businessman whom the Slovakian authorities charged with the murder of Kuciák and Kusnirová. Muscat’s downfall came about partly due to his alleged ties to Yorgen Fenech, a magnate whom the Maltese authorities charged with the assassination of Caruana Galizia. Civil society organisations have repeatedly accused Muscat and Fico of creating a political environment that helped Italian criminal groups flourish in their countries.

Given how Hungary and Poland dominate public discourse on the EU’s efforts to combat state-linked graft and illiberal governance, it can be easy to forget that the rule of law is under threat in other member states too

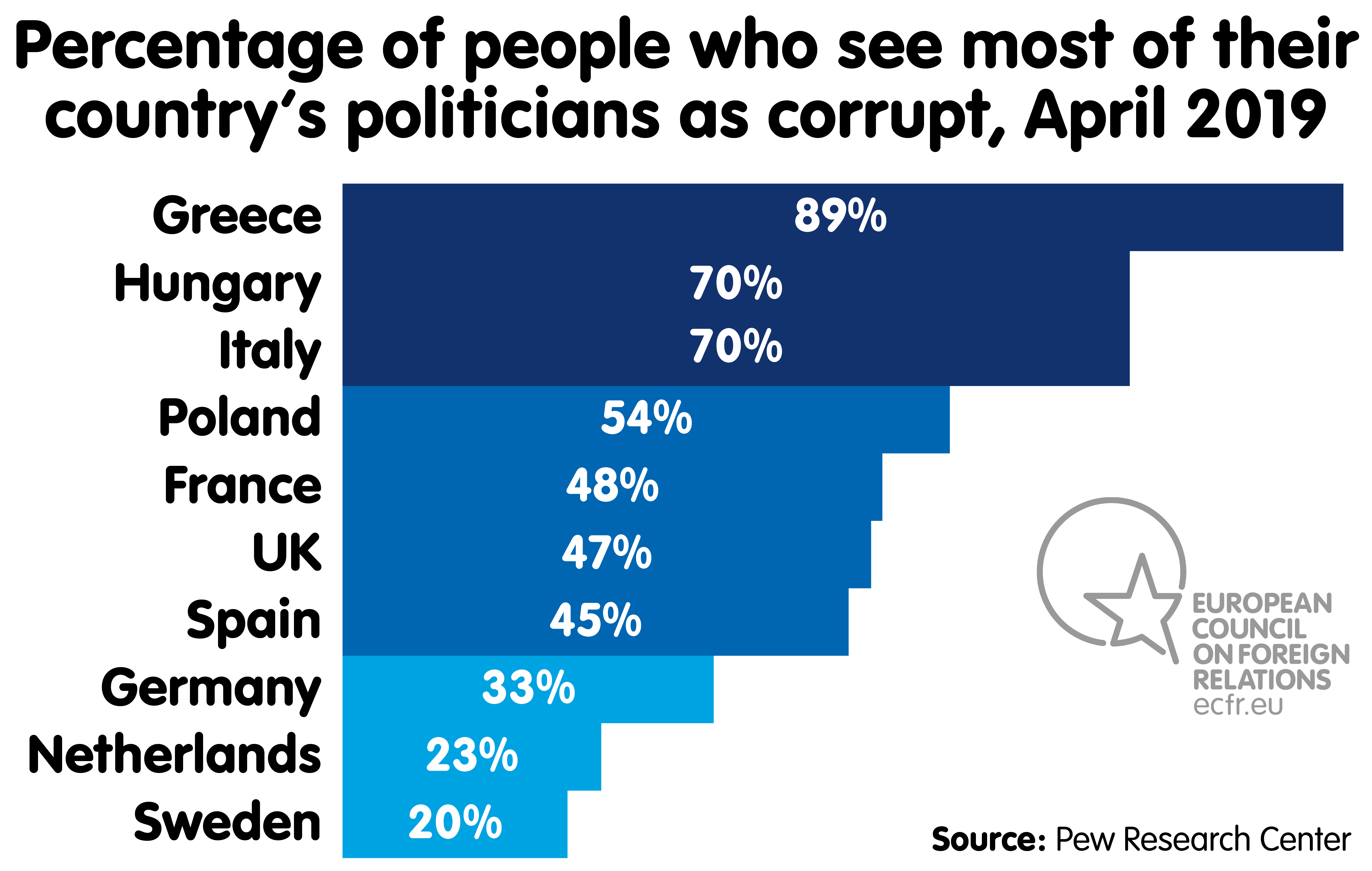

Although it is a good sign for liberal democracy in Europe that many Maltese and Slovakian citizens rejected leaders they deem corrupt, the developments that led them to do so are anything but encouraging. Given how Hungary and Poland dominate public discourse on the EU’s efforts to combat state-linked graft and illiberal governance, it can be easy to forget that the rule of law is under threat in other member states too. Corrupt actors in Malta and Slovakia allegedly attacked the sinews of democratic society through not only the killing of Caruana Galizia, Kuciák, and Kusnirová – which, as Reporters Without Borders discusses, damaged freedom of the press – but also persistent efforts to shift the role of the state away from the provision of public goods and towards support for personalised criminal networks.

They appear to have done so in ways that are reminiscent of some of the world’s most destructive kleptocracies. Appropriately enough, Matovic’s campaign tactics partly resembled those used by Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny: the Slovakian focused on publicising the allegedly ill-gotten gains of high-profile figures connected with SMER, livestreaming a tour of a former finance minister’s luxury property in France to 1.6 million people and attempting to investigate shell companies owned by Penta Investments. In a similar vein, Fenech’s Dubai-based 17 Black and Kocner’s Malta-based International Investment Development Holdings are allegedly implicated in the kind of cross-border financial crime that thrives under kleptocratic regimes. Indeed, in December 2019, the US Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctioned Kocner for human rights abuses under the Global Magnitsky Act.

The fallout from Fico’s and Muscat’s alleged activities seems to confirm an observation that global institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have made for several years: endemic corruption can play havoc with countries’ political and even macroeconomic stability – not least because of its capacity to generate public discontent, particularly among young people. Moreover, one need only reflect on US President Donald Trump’s treatment of Ukraine in the past year to see how alleged assaults on the rule of law can become a strategic problem. When a national leader acts in this way, even a powerful state with robust democratic institutions can struggle to implement a coherent foreign policy.

Nonetheless, many European governments have the power to counter state-backed corruption and financial crime – they only lack the political will to do so. As I argue in a new report for the European Council on Foreign Relations, those that gain the will to act should begin by creating national institutions focused on the task. Such institutions should, for instance, establish transparency and enforcement mechanisms that end corruption networks’ abuse of offshore havens. And they should constrain kleptocrats’ enablers in Europe through reform of laws and enforcement practices covering the financial and professional services industries. Over time, these institutions could help European states build an international coalition that addressed the threat from kleptocracy in a lasting fashion.

At this stage, one can only guess whether a government led by OLaNO – which, as an inexperienced single-issue party, remains something of a mystery – will pursue the ambitious reforms needed to loosen corruption networks’ alleged hold on the Slovakian state. But all European leaders should try to learn from its election victory. If they refuse tackle corruption as both a threat to domestic stability and their foreign policy initiatives, they could soon find themselves out of a job. It seems only a matter of time before opposition parties across Europe come to the same conclusion as Matovic: anti-kleptocrat campaigns can tap the deep frustration with elites that has reshaped European politics throughout the past decade.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.