Europe’s emigration paradox

Emigration is as much a worry for some European citizens as immigration, if not more so. What should the EU and member states do about this?

Here is a live paradox that too few European or national policymakers have yet acknowledged. The citizens of several European Union countries consider the freedom to live and work in other member states one of the most important elements of European integration. But in these very same countries, concern is also high about the fact that people exercise this freedom by moving elsewhere. These are mostly to be found in the EU’s east and south: every second person in Romania, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Greece, Spain, and Slovakia say that they would miss freedom of movement if the EU were ever to come to an end. At the same time, in Romania, Poland, and Hungary – as well as in Italy, Spain, and Greece – people fret about emigration more than they do about immigration. Often, they are concerned about both. In contrast, just a quarter of Danes and Dutch worry about losing freedom of movement, and even fewer about emigration.

If people feel that they lack a better future where they are, many of them will continue to vote with their feet.

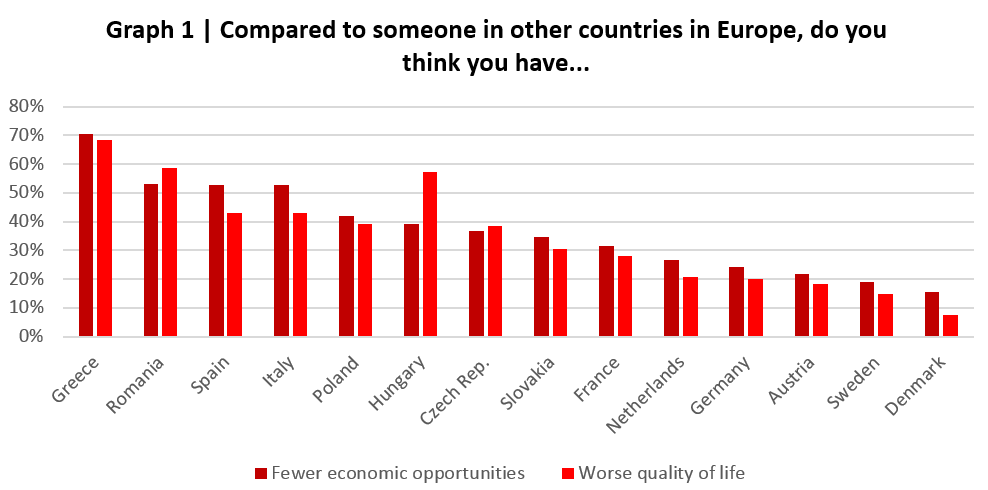

Their fears are not without basis: hundreds of thousands of Poles, Spaniards, and Romanians moved to other EU members over the last few years. This may be one of the reasons for the resentment about emigration in the EU’s periphery countries. Over 50 percent of voters in Italy, Spain, Romania, and Greece are convinced that they face less promising economic prospects than people elsewhere in Europe, as ECFR showed in May. They also often believe their quality of life to be inferior to that of other EU member states (see Graph 1).

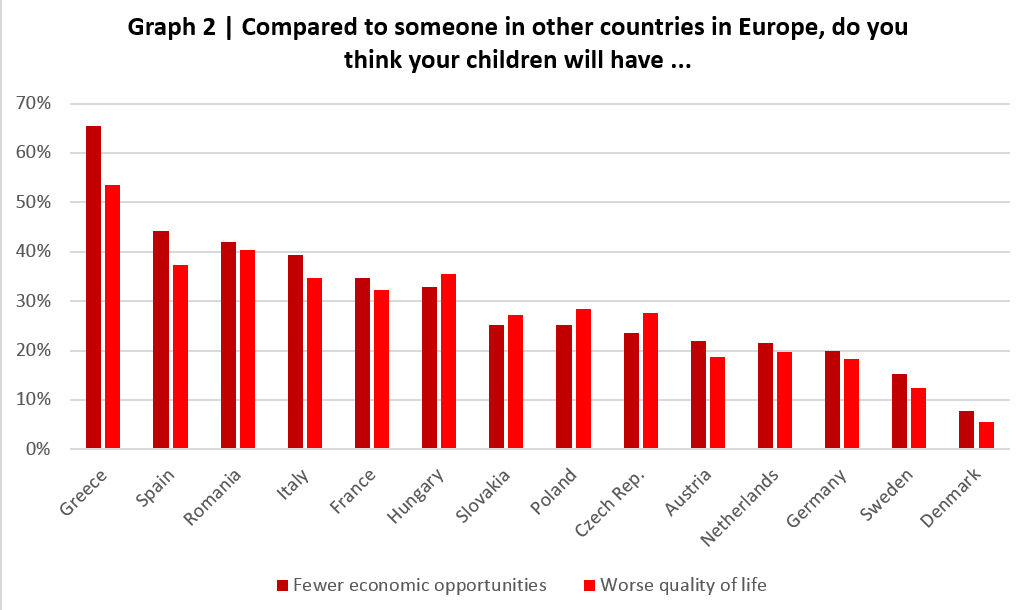

Worse: Poland aside, these citizens do not expect this situation to improve much for their children (see Graph 2).

Our research shows that many voters who hold this belief also hold pro-European and progressive views – but they are nevertheless frustrated at the current situation. This is probably because they do not feel they can spread their wings at home; or they may have seen that things work better elsewhere.

How should European policymakers respond to such concerns? There is no easy fix for public anxiety about emigration, but there are some possible ways forward. If people feel that they lack a better future where they are, many of them will continue to vote with their feet. And even the fanciest system of fiscal incentives for people to come back home – which are tried worldwide, from Italy to Malaysia – makes little sense if it is not accompanied with structural reforms. To a large extent, the problem looks typically national; and so the solutions should be domestic. Member state governments should therefore do their homework in providing favourable conditions for both economic and human flourishing. This means a whole range of things: from improving the ease of doing business, to ensuring air quality, to providing good schools, kindergartens and healthcare, to instituting good governance and fighting corruption. These are the fundamentals which can not only draw people back home (and attract newcomers), but also encourage people to stay in the first place.

Policymakers should seek to identify locally led community cohesion policies that provide hope that places experiencing emigration can succeed.

However, the cultural dimension of this issue deserves acknowledgement, as the question is far from being just an economic one. Emigration does not operate in isolation from other sociocultural trends that together form the elements of globalisation. In other words, people moving country can contribute to those they leave behind feeling their traditional way of life is coming to an end. This may be the case either if a place depopulates or if migrants from elsewhere come and do the work that local citizens used to do. There is no inevitable causal link between some people leaving and a growing sense that a community is in decline – but emigration can become an easy scapegoat. Given this, policymakers should seek to identify locally led community cohesion policies that provide hope that places experiencing emigration can succeed. This may even include finding a new purpose for such places, as happened, for instance, with Sant’Alessio, a tiny village in southern Italy, which was reinvigorated by migrants.

And then, apart from actions on the national and local level, there is also a role for European action. In many of the newer members, the EU itself still tends to be strongly associated with the freedom of movement: a fundamental right, recognised by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was not, however, guaranteed back in the times of the Iron Curtain. One task for the EU is to become serious again about socio-economic cohesion, such as by using structural funds to support education, healthcare, and other public services more vigorously in the member states.

European policymakers may also wish to look again at eurozone enlargement and reform, to address the fact that being outside the common currency area (or being in it, but with much higher risk premiums) means countries are effectively second-tier EU members. And some EU countries – including France, Germany, and the Netherlands – are still preventing Romania, Bulgaria, and Croatia from joining the Schengen area; they should reconsider their opposition. In many ways, the solution may lie in returning to the principle of convergence and ensuring high minimum standards across the EU. This is not just for economic issues: the EU should continue to defend democracy and rule of law, and maintain the fight against corruption, so that democratic backsliding at home does not join the list of push factors for citizens to leave.

On this last point, the risk that the EU’s Article 7 mechanism could become a dead letter seems to have fallen away, for the moment at least, given the failure of anti-European parties to win more than one-third of seats in the new European Parliament (the threshold needed to halt the Article 7 procedure progress in the European Parliament). Besides, European voters sent a strong message to political leaders in May: the defence of democracy and economic considerations featured among key factors behind how they voted and whether they voted at all, as ECFR explained in June. This included analysis of the campaign manifestos of all parties that got into the new European Parliament, and it also showed that there is now likely to be more public acceptance of eurozone reform and changes in the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) was expected before the election.

To be sure, eurozone members continue to be deeply divided on pushing integration further, while some of the remaining non-members – like Poland and Hungary – display little interest in joining the club. And the growing fragmentation in the Council, which may favour the status quo over new ambitions, hampers a significant overhaul in the new MFF. But the new post-election institutional opening creates a rare opportunity for a fresh start and for the recalibration of priorities.

For this to happen, the member states would have to acknowledge emigration as an issue demanding joint consideration, whether they are countries of origin or of destination. After all, was much of the Brexit vote not due to the frustration with workers from the east? Is intra-EU ‘welfare tourism’ not a big concern in Denmark? And was Macron’s focus on reforming the Posted Workers directive not a consequence of French citizens’ earlier complaints about Polish plumbers? As surprising as this may sound, the emigration agenda may become one of the areas in which Warsaw, Budapest, and Rome could constructively seek joint solutions with Madrid, Paris, and Berlin.

And the new European Commission and European Parliament should not leave this issue to member states alone. Together, they should not seek to hamper mobility, as this is so fundamental for European citizens, but they need to work to stop the spiral of resentment between the EU’s centre and periphery. Left unaddressed, whether countries are seeing people leave or arrive, across Europe emigration could contribute to a dangerous perception that ‘the system is broken’ and that the EU is largely to blame.

NOTES ON GRAPHS

Figures include only people who answered ‘fewer economic opportunities’ and ‘worse quality of life’ to two questions: (a) ‘Do you think you have more, fewer or the same economic opportunities as someone in other countries in Europe?’, and (b) ‘Do you think you have better, worse or the same quality of life as someone in other countries in Europe?’.

Figures include only people who answered ‘fewer economic opportunities’ and ‘worse quality of life’ to two questions: (a) ‘Do you think your children will have more, fewer or the same economic opportunities as someone in other countries in Europe?’, and (b) ‘Do you think your children will have better, worse or the same quality of life as someone in other countries in Europe?’.

Data for both graphs is based on the public opinion poll conducted by ECFR and YouGov in March 2019. Countries polled included: Austria (sample size: 1,000), Czech Republic (1,000), Denmark (1,400), France (1,000), Germany (1,000), Greece (500), Hungary (1,000), Italy (1,000), the Netherlands (1,000), Poland (1,000), Romania (1,000), Slovakia (500), Spain (1,000), and Sweden (2,000).

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.