Denmark’s shift towards an ever greener union

With a domestic debate on the EU looming, the Danish government appears likely to strike a new agreement on its Europe policy.

Danish voters went to the polls twice within two weeks this summer, casting their votes in first European and then national elections. The results of the contests mark a significant shift towards green and centre-left parties – at the expense of the political fringes, particularly right-wing nationalists. As such, trends in Denmark run counter to the surge in protest politics that has spread across Europe in recent years. This promises to affect Denmark´s cohesion with the rest of the European Union in several important ways.

Increasing EU cohesion

Following three weeks of intense negotiations, the Social Democratic Party announced a common “letter of understanding” with its Social Liberal and left-wing partners. This allowed it to form a one-party government, making Mette Frederiksen the second female prime minister of Denmark and the youngest person to hold the office. The letter, which sets out the objectives of the administration, reflects the government’s high socially progressive and green ambitions for Denmark. The government commits to limiting economic and gender inequality, as well as to strengthening the welfare state. Most strikingly, it sets the goal of cutting greenhouse-gas emissions by 70 percent compared to 1990 levels before 2030, one of the most demanding such targets in the world.

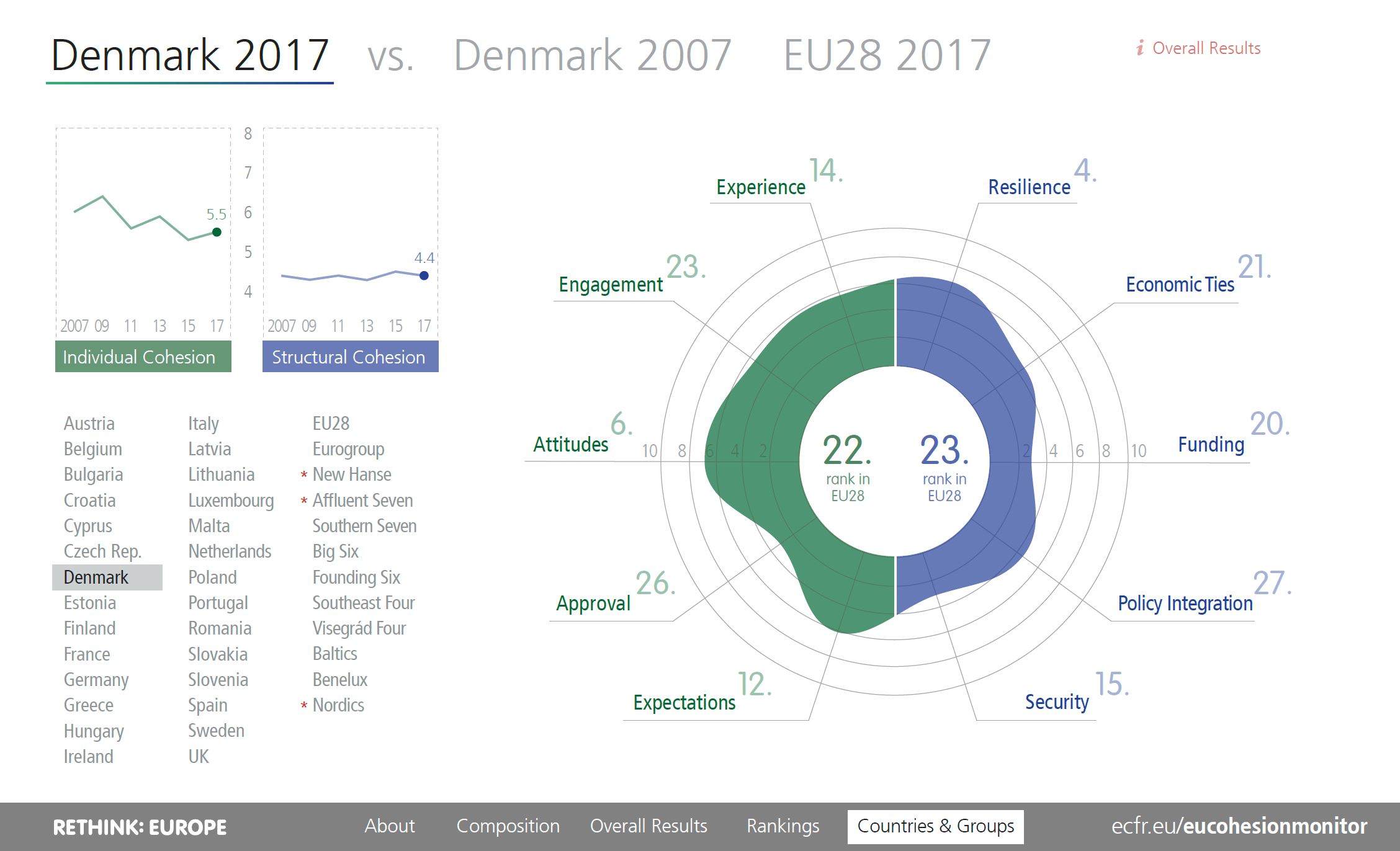

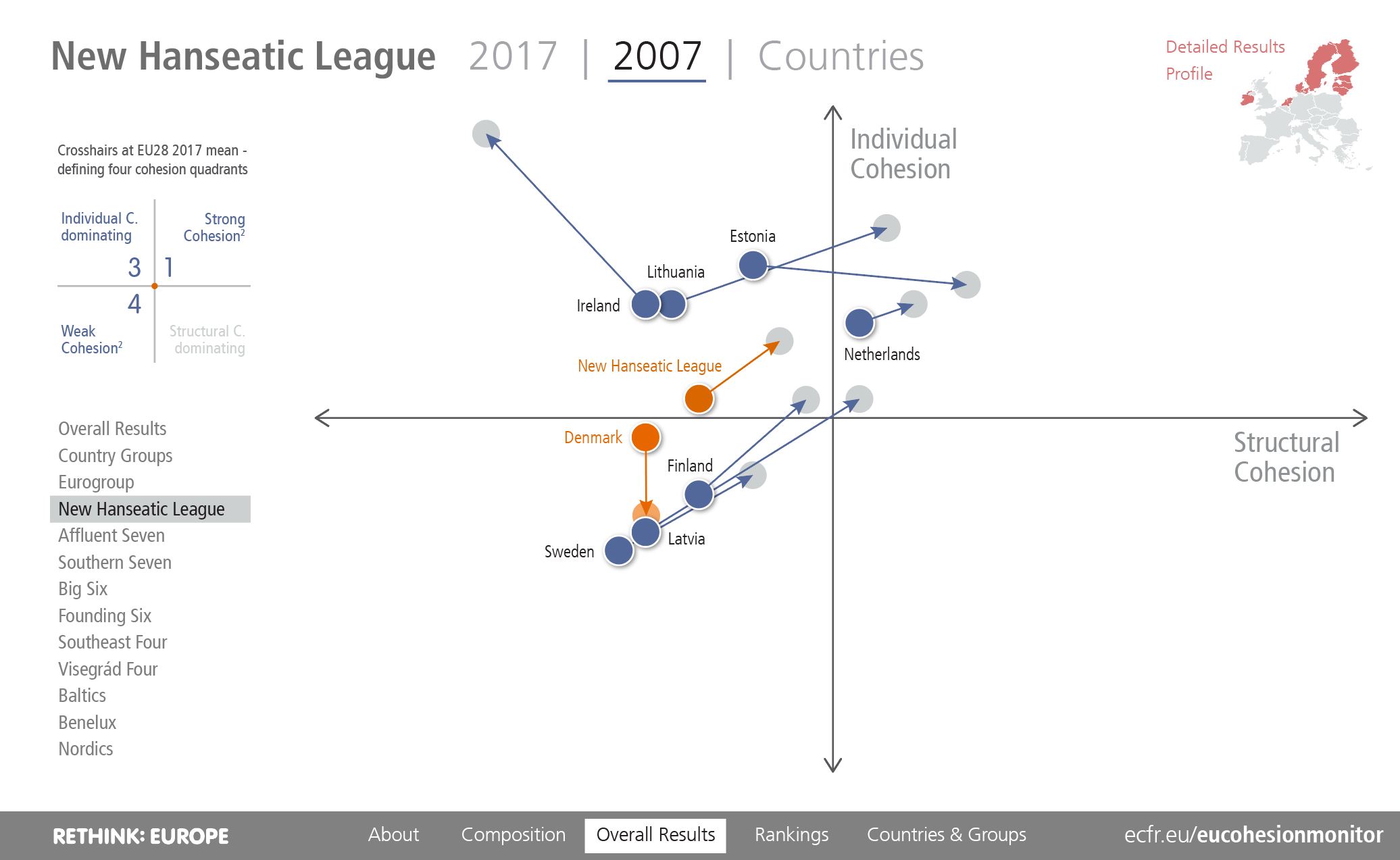

But does this turn towards socially progressive and green policy suggest that Denmark will adopt a more positive attitude towards the EU? The country is widely regarded as hesitant about its membership of the EU, as symbolised by its four opt-outs on significant aspects of EU cooperation, including home and justice affairs, economic governance, citizenship, and defence. These Eurosceptic sentiments affected Denmark’s rankings in the European Council on Foreign Relations’ EU Cohesion Monitor in 2017 (the latest available data in the study): 22nd place in individual cohesion, and 23rd place in structural cohesion, among the EU28. However, since the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency and the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the EU in 2016, Denmark has developed a tendency towards greater individual and structural cohesion.

In individual cohesion, current polls suggest that Danish support for EU membership is increasing. Indicators of Denmark’s engagement appear to be rising: the country’s voter turnout in the May 2019 European election was its highest ever. The same is true for the country’s attitudes: the share of votes for anti-EU parties almost halved in Denmark’s European and national elections. Beyond individual cohesion, there have been improvements in Denmark’s resilience – including its economic performance in GDP growth and unemployment – and political integration, with the country engaging in a renewed political debate about ending its defence opt-out. These factors point towards greater structural cohesion.

Still a hesitant EU member

Despite these developments, the EU has not taken centre stage in Denmark’ national or European election campaigns – nor in the new government’s policy platform. The bloc’s absence can be at least partly explained by disagreements among the parties that support the government. While the Social Liberal party has the most pro-EU policy in the Danish parliament, the far-left socialist party – the Red-Green Alliance – remains EU-sceptic, calling for Denmark to renegotiate its relationship with, and potentially leave, the bloc.

The Social Democratic Party also has an ambiguous relationship with the EU. Frederiksen has taken the party in a less pro-EU direction since becoming its leader, in 2015. Back then, she stated that Denmark “belonged on the periphery of EU cooperation”. She has since claimed that Denmark’s EU membership should be based on the four opt-outs. Nonetheless, key ministers in the new government belong to the pro-EU wing of the Social Democratic Party and have experience working in EU institutions. One such figure is the foreign minister, Jeppe Kofod – who, shortly before his appointment to the post, was re-elected as a member of the European Parliament.

Moreover, the new government is making changes to the substance of its main policies as it increasingly realises that some challenges can only be solved at the European level. This can be seen in its two main priorities: climate policy and an economic policy that promotes equality. As the letter of understanding puts it, “despite differences in opinion among the parties regarding Danish membership of the EU, agreement has been reached that Denmark as member of the EU must work for a far more progressive EU policy than it has today”.

Accordingly, the government has set the goal of transforming the EU from a primarily economic union into a climate union. Here, it aims to make the EU’s 2030 climate goals more ambitious, pushing for the bloc to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 and to gain long-term energy autonomy. Similarly, it aims to fight social dumping, tax havens, and tax arbitrage. As part of her push to implement these policies, the prime minister has voiced unreserved support for reappointing Social Liberal Danish politician Margrethe Vestager as the EU commissioner for competition – a role in which she has worked extensively on regulating and taxing multinational companies.

Translating greater cohesion into lasting policy

With a domestic debate on the EU looming, the Danish government looks set to strike a new agreement on its Europe policy, which it last updated in 2008. Such a document could sustain Denmark’s shift towards greater individual and structural cohesion, by binding most Danish parties into a common understanding of their country’s approach to the EU. This agreement will reveal whether the new Danish government will work towards an ever greener union from the periphery or the centre of the EU.

The EU Cohesion Monitor

The EU Cohesion Monitor is an index of the 28 member states of the European Union and their readiness for joint action and cooperation. It measures how strong cohesion is, how it is changing, and how much it differs between the member states of the EU.

The EU Cohesion Monitor combines a total of 42 factors to measure cohesion according to five individual and five structural cohesion indicators. The individual indicators quantify cohesion at the level of citizens’ experiences, opinions, and expectations. The structural indicators measure cohesion at the macro level of the state and the economy.

Download the new edition of the interactive EU Cohesion Monitor Explorer (interactive PDF: 67 MB)

The EU Cohesion Monitor is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe data project, which is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

Christine Nissen has been an associate ECFR researcher since 2014. She is a researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies in Copenhagen.

Jakob Dreyer is a PhD fellow at Copenhagen University and former officer in the Danish army.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.