Conservatives without a cause? The German youth’s view and what it means for Europe

Retaining what they have is largely enough for millennials – despite the fact that the majority feels that the EU is not on the right path.

Read more about the German youth's view in the policy brief The Young and the Restful: Why young Germans have no vision for Europe.

After years during which millennials – the generation born after 1980 – were little more than the punchline for jokes, they have begun to take on an important role in European countries. In the United Kingdom, following a Brexit vote that the old won at the expense of the young, a “youthquake” shook British politics as many young people rallied behind Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, contributing to the Conservative Party’s loss of its parliamentary majority. “Youthquake” became Oxford Dictionaries’ word of 2017, a year that saw the 39-year-old Emmanuel Macron become president of France and a 31-year-old become Austrian chancellor.

This could spell change for the European Union – itself a millennial, born in 1992 with the signing of the Maastricht Treaty – which is in dire need of the kind of new ideas and new vision that a youth uprising could deliver. However, for this task of renewal, Europe had better not count on young Germans. ECFR’s new policy brief , based on polls – particularly the Körber Stiftung’s 2017 Berlin Pulse poll, broken down by age groups[1] – and interviews with young German politicians, looks at what Germany’s Europe policy would look like if the young determined it. Overall it is a comparatively unambitious view: German millennials are strikingly conservative and oriented towards the status quo.

German millennials are very similar to their elders in one way: they lack vision. As I’ve pointed out before, Germans take pride in having moved beyond ideology, and are wary of any kind of political “vision”. In a country that lived through the Nazi dictatorship and that broke into two because of communist ideology, this aversion to political ideologies used to be a sensible choice. Yet it has become a fetish that bans not only ideologies but all kinds of political visions, hampering Germany’s ability to act.

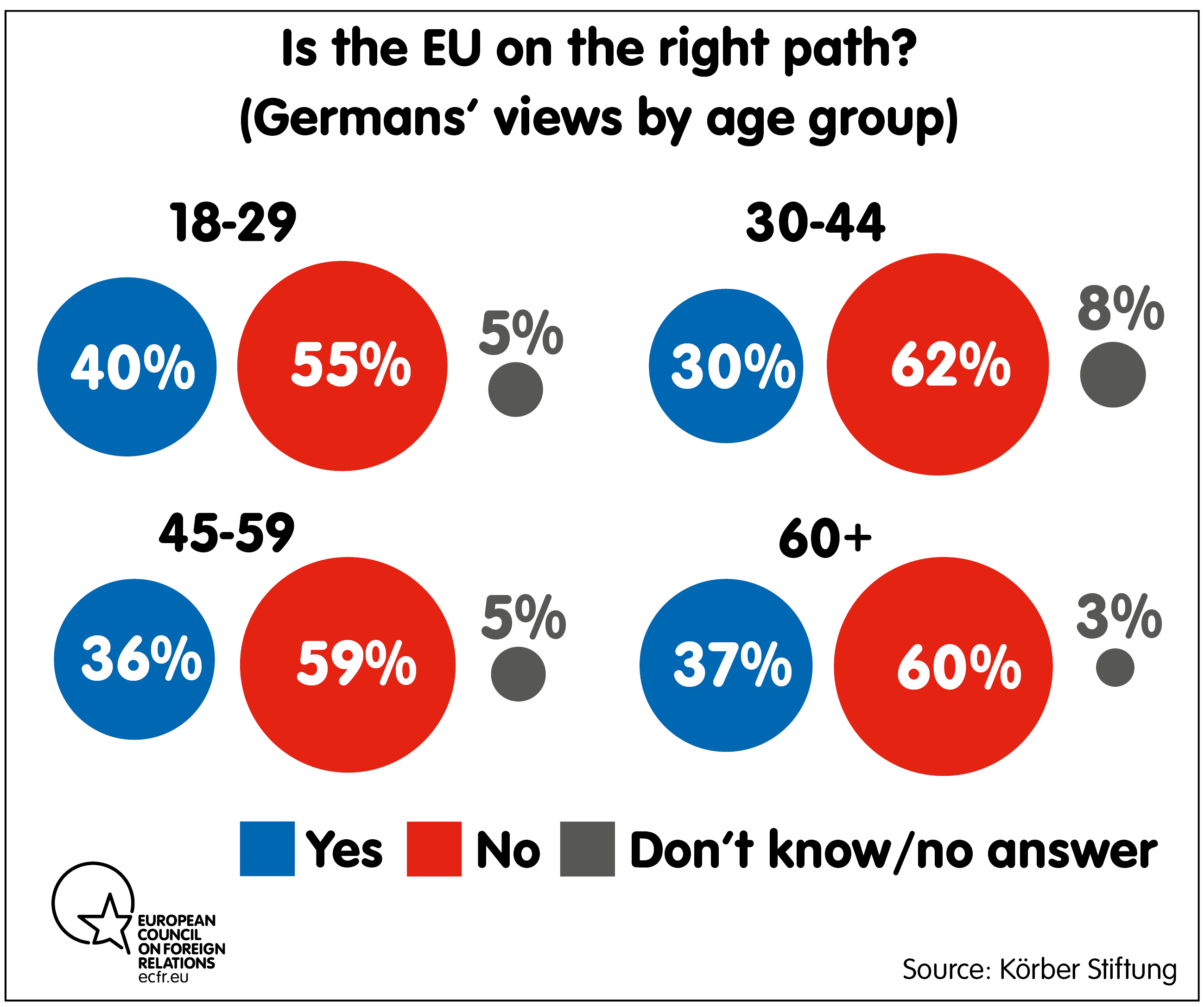

Like their parents, young Germans think rather small. Retaining what they have is largely enough for them – despite the fact that the majority feels that the EU is not on the right path (this view is less prevalent among millennials than other age groups).

Most German millennials regard the EU as a success story, and fear that its achievements may eventually be lost because many take them for granted. Defending the status quo has thus become the common denominator in German millennials’ views. Young Germans’ ideal EU, it appears, is an EU carefully led by Germany (39% of German millennials think Germany should take on more of a leadership role) and focused on European unity, peace, and ecology. It is the ideal of an EU that could afford the luxury of indifference to the outside world.

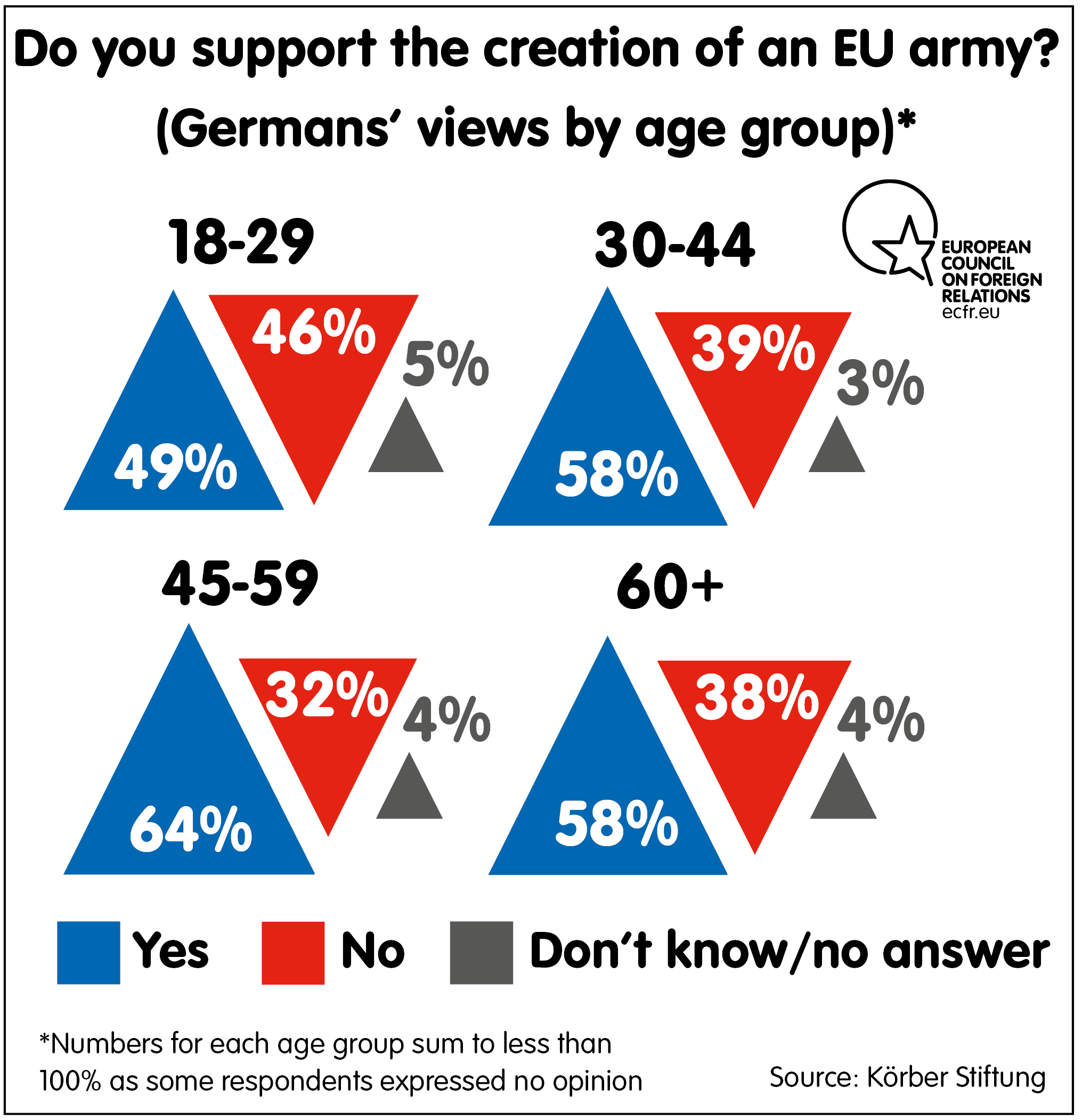

In anything military, young Germans’ views are stereotypically German. Although 58% of all Germans like the idea of a European army, less than half of those aged between 18 and 29 hold this view – the lowest proportion of any age group.

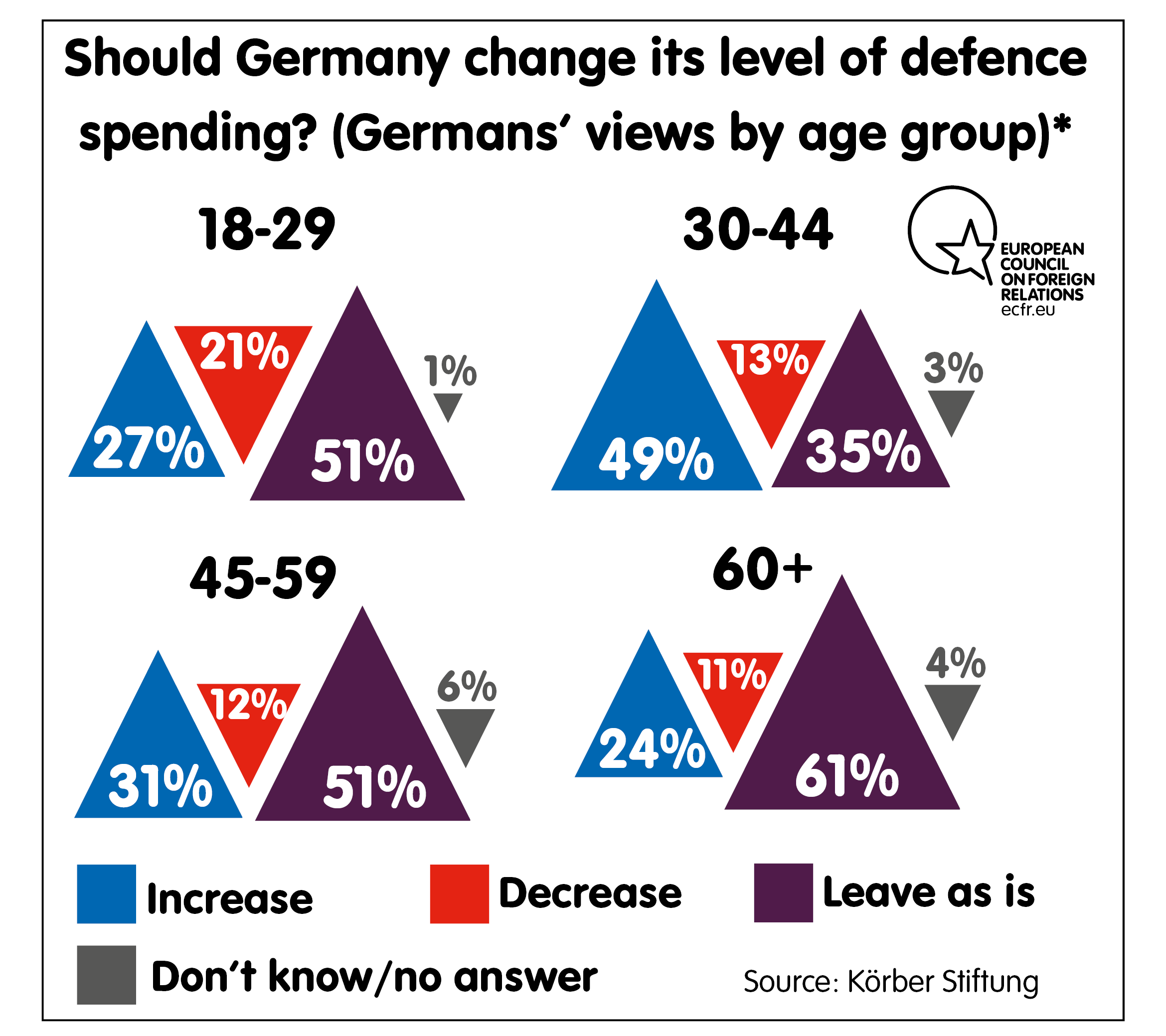

In the same vein, 21% of German millennials would like to decrease Germany’s already low defence budget, compared to 12% of the other age groups (the majority advocate no change in spending).

These views, focused on the status quo, may help explain why conservative parties enjoy comparatively high support – the CDU/CSU’s youth organisation Junge Union is, with 109 000 members, Germany’s largest political youth organisation. In his 1956 essay, “On Being Conservative”, the philosopher Michael Oakeshott wrote that to be conservative “is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss”. This appears to accurately describe young Germans in 2018.

And yet: under this apparent complacency hides some discontent. A poll revealed that an extraordinary 83% of Germans between the ages of 18 and 29 believe their generation is not sufficiently represented in German politics.[2] And Germany just lived through its own small “youthquake”. During the coalition negotiations, 28-year-old Kevin Kühnert – head of Jusos (Young Socialists), the youth organisation of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) – came close to toppling the coalition deal between the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union and the SPD. Due to the dismissive way that the media initially covered this “dwarf uprising”, many young Germans began discussing their experiences of being treated dismissively due to their age under the hashtag #diesejungenleute (“these young people”). This discussion even led Angela Merkel to include younger voices into her cabinet – including the 37-year-old Jens Spahn, one of her most important critics.

It thus appears likely that millennials may begin to play a more important role in German politics. But given the aforementioned survey results, fundamental revolutions driven by the young appear unlikely

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.