Cohesion or disintegration? Germany’s European election campaign

“Zusammenhalt” is a buzzword in the European election manifestos of the German parties. But what does it exactly mean in the political discourse?

Cohesion, in all its guises, plays a huge role in German public discourse on the upcoming European Parliament election. Most Germans would be unfamiliar with a direct translation of the term “cohesion” as “Kohäsion”. At best, politically engaged Germans might associate the word with the European Union’s cohesion policy. Those familiar with the policy understand that it involves EU budget lines designed to help close the socioeconomic gap between rich and poor regions, through the provision of co-funding. As such, cohesion in this narrow sense is linked to a debate about solidarity and sharing within the EU – although the term “Kohäsion” is rather cool and technical. “Zusammenhalt”, the German equivalent of the Latin word “cohaesum”, carries much more emotion: it means “togetherness” in the sense of both being in the same place and belonging together. As a consequence, Germans associate “Zusammenhalt” with an enduring bond.

The word has a strong visual presence in Germany’s European Parliament election campaign. The campaign posters of the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and Bündnis90/Die Grünen (Green Party) draw on the rhetoric of community more than other parties, emphasising togetherness and “our Europe” while referring to the strength and protection the EU should provide. Indeed, “Zusammenhalt” appears 14 times in the Green Party manifesto, 13 times in the SPD manifesto, and eight times in the CDU/CSU manifesto. In contrast, the word features three times in the manifesto of Die Linke, twice in that of the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP), and only once in that of the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Zusammenhalt means “togetherness” in the sense of both being in the same place and belonging together

The frequency with which parties use the term corresponds to their commitment to European cohesion as a concept. This trend is most obvious in the case of the AfD. The party’s manifesto only mentions cohesion in the context of immigration, as part of its argument that “many European governments have tried to compensate for a shrinking population with immigration, though this has been proven to be wrong and would lead to massive problems with cultural and social cohesion” (p. 65).[1] Interestingly, the FDP uses “Zusammenhalt” in the same context, but states its support for immigration and adds: “we are aware that the cohesion of society and its capacity to integrate (migrants) must not be disregarded” (p. 53). In its other mention of cohesion, the FDP manifesto deals with EU cohesion policy, which it would like to thoroughly reform by prioritising the European Fund for Regional Development over other funding schemes (p. 25).

The CDU/CSU manifesto speaks a very different language. Its title, “Our Europe gives strength”, draws on a common idea of Europe as its main theme. This should be read as meaning both “the Europe that we want” and “we/us in Europe”. The concept of Zusammenhalt is reflected in the title of chapter 3, “Our Europe stands together”, and the word itself appears in one of the subtitles of that chapter, “Together we are strong: Our Europe creates new cohesion”. The CDU/CSU sees the sense and experience of togetherness in Europe as “the core of the European idea, of a common understanding and for European cohesion” (p. 2). In another section, the CDU/CSU manifesto states the need for a strong European response to internal and external challenges that preserves prosperity, security, and cohesion now and in future (p. 8).

The SPD manifesto emphasises Zusammenhalt even more. Its title, “Come together and make Europe strong”, alludes to power and togetherness. And the SPD also assigns a full chapter to cohesion, entitled “For a Europe that stands together”. In the party’s view, cohesion is not inevitable but the product of a new approach to working together in the EU, which requires protection against narrow economic logic and external actors’ efforts to undermine European cohesion. The SPD manifesto states: “together we can defeat nationalism. Cohesion is the key to act against fears about the future, unrest and crises in some member states … Cohesion implies a coming to terms with one another” (p. 8). Europeans, the manifesto claims, should not allow themselves to be guided by short-term national interests alone. Meanwhile, Germany “has to always keep an eye on compromise among member states and on overall cohesion”. Elsewhere, the SPD manifesto mostly links cohesion with social justice and economic redistribution.

While the SPD manifesto discusses the negative effects of austerity measures in relatively broad terms, the Die Linke manifesto uses stronger language on the issue. For Die Linke, cohesion has social connotations above all else. The party claims to fight for a “social Europe … one in which cohesion grows and not inequality or exploitation” (p. 6). Moreover, it accuses the German government and the European Commission of having “systematically weakened social cohesion by pursuing policies of fiscal austerity and privatisation” (p. 20).

The Green Party manifesto also emphasises the social dimension of cohesion and devotes a chapter to strengthening cohesion. Entitled “Strengthen what keeps us together: Deepening the economic, monetary and social union”, this chapter spells out the social aspect of cohesion in terms similar to those used by the SPD and Die Linke. For example, it states that “European cohesion means guaranteeing legally protected social rights to all people, implemented everywhere in the EU” (p. 50). The Green Party believes that it is in Germany’s interest to place more emphasis on cohesion and solidarity within the eurozone, and to refrain from seeking economic advantages over other states by lowering wages and social standards – as the country has, thereby weakening its own social cohesion and that of its European neighbours (p. 70). While most references to cohesion in its manifesto fit within this socioeconomic narrative, the Green Party discusses one aspect of cohesion that its rivals do not. Dealing with social media in general and hate speech in particular, the manifesto concludes that the “cohesion of society crumbles under the power of lies and disinformation” (p. 163). To counter this, the Green Party pledges to support investigative journalism, as well as media education.

Overall, cohesion has two major features in the German political discourse on Europe. The concept is important to appeals to social inclusion and equality. “Zusammenhalt” presupposes a social balance, reflecting the general preferences of the public and political parties in Germany. Cohesion is also key to emphasising community and togetherness – and, as such, relates to the issue of social equality. In the EU context, references to “our Europe” are not meant to be read as a “German Europe”. Rather, they reflect a desire to remain part of a larger community that should be strengthened and protected.

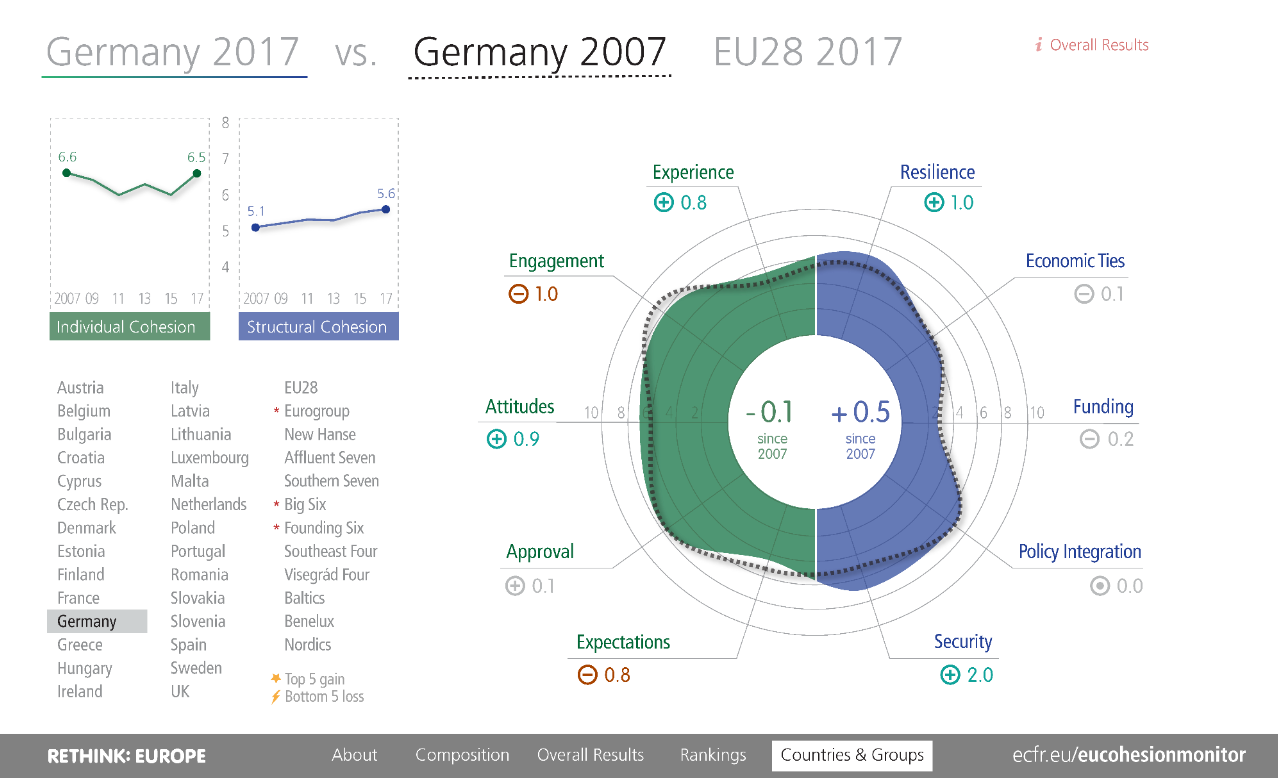

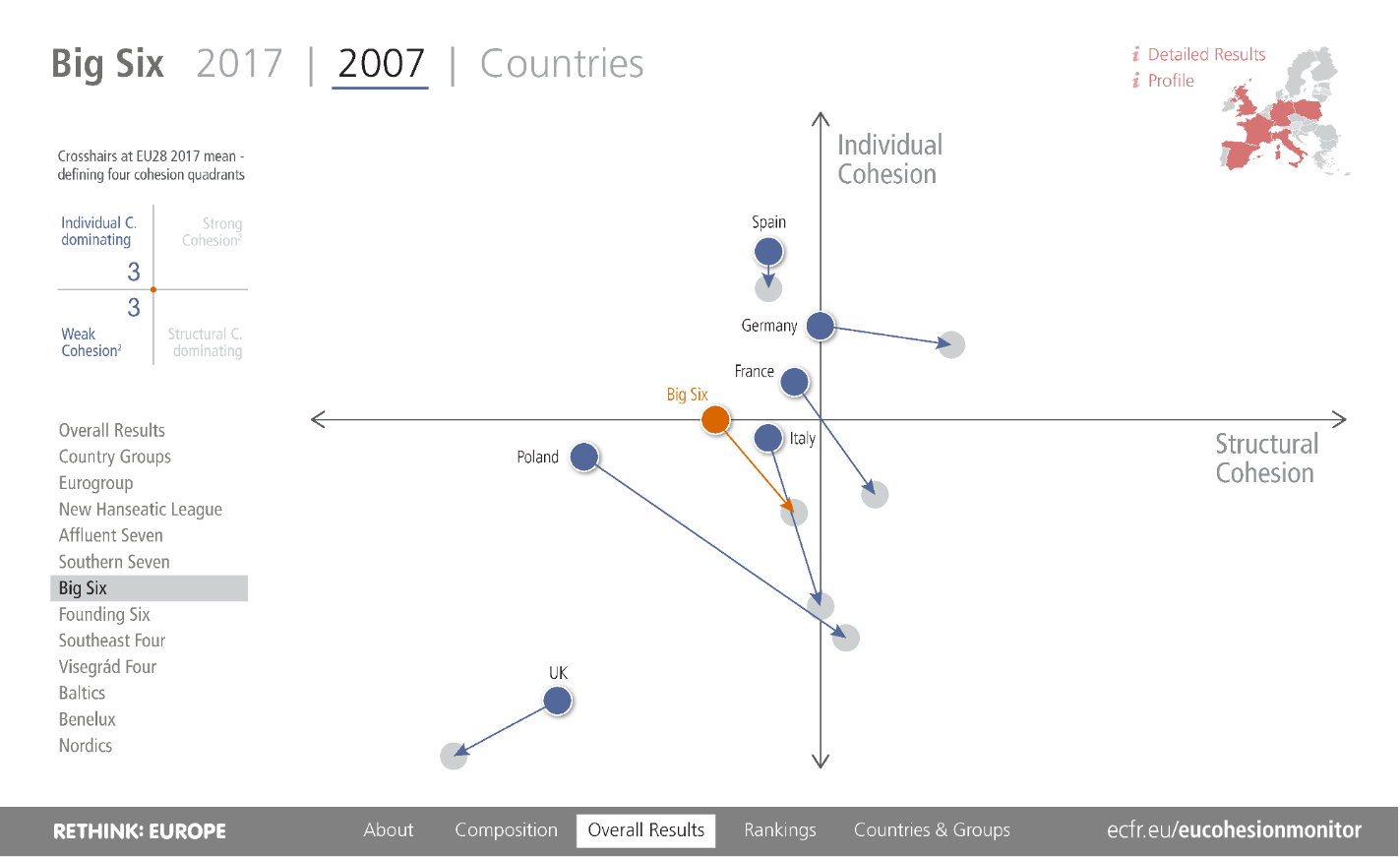

These trends are reflected in the latest edition of ECFR’s EU Cohesion Monitor. In 2007, before the global financial crisis, Germany was grouped with Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands as the only EU member states that benefited from strong cohesion – that is, rated above the EU average in cohesion indicators at both the macro-level (such as trade, funding, and security cooperation) and the micro-level (such as experience, engagement, and expectations). In the past decade, Germany’s overall level of European cohesion has remained remarkably stable, only experiencing declines in its engagement indicator (reflecting voting behaviour) and its expectations indicator (reflecting views about the future). However, two of the major crises during that period have had a noticeable effect on cohesion. In both 2011 and 2015 – during the euro crisis and the migration crisis respectively – individual cohesion declined, before returning to almost the same level as before. None of the EU’s other large member states has demonstrated European cohesion as resilient as Germany’s (Spain came closest to doing so). This likely explains why cohesion plays such an important role in the electoral campaigns of German parties that aim to enter, or remain in, government.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.