Brexit bravado: Can the UK build a new continental coalition?

EU member states’ high regard for Britain in security and defence may be on the wane. What can London do to stop the slide in the post-Brexit era?

A regular refrain of the post-Brexit referendum era is the public expression – by both the United Kingdom and the European Union – of support for strong cooperation on foreign, security, and defence policy. British Prime Minister Theresa May’s Florence and Munich speeches stressed the mutual benefits of this approach: she was at pains to position her country as an invaluable partner for the EU in these areas. For its part, the European Commission has signalled its preference for strong, enduring security relations.

Yet – despite their importance – foreign, security, and defence policy have not featured too prominently in the wider Brexit debate. Perhaps, paradoxically, this in part because of their significance: there has been a sense of inevitability about continued UK-EU cooperation in some form or another after Brexit, leading both sides to rest on their laurels somewhat. Indeed, maybe the sheer complexity and sensitivity of such cooperation has led to creeping inertia in the Brexit negotiations – with the UK and the EU deferring discussion on these policy areas to an imagined distant point when they have worked out the “less significant” aspects of a future relationship. However, it is likely that, despite their shared rhetoric of cooperation, there is growing a divergence – in both rhetoric and practice – between the UK and the EU that is leading them towards something of a stalemate.

At the present time, there is not even an outline available of the types of security and defence activity the UK may be able to partner on

As Brexit draws nearer, the EU is doubling down on its basic principles. It seeks to protect its strategic autonomy and continues to intone the mantra that third countries cannot enjoy the same benefits as full members, including even close partners such as the UK – which still wants to have privileged and bespoke access to policy- and decision-making. The EU has also issued a strong response to May’s attempts to use security cooperation as a bargaining chip in negotiations – stressing, again, the parties’ shared interest in cooperation, but also highlighting that it will not be held to ransom. And the EU appears to be sticking to this stance. The situation poses real and immediate questions for the UK in terms of ensuring that its “Global Britain” ambitions survive, never mind become a reality.

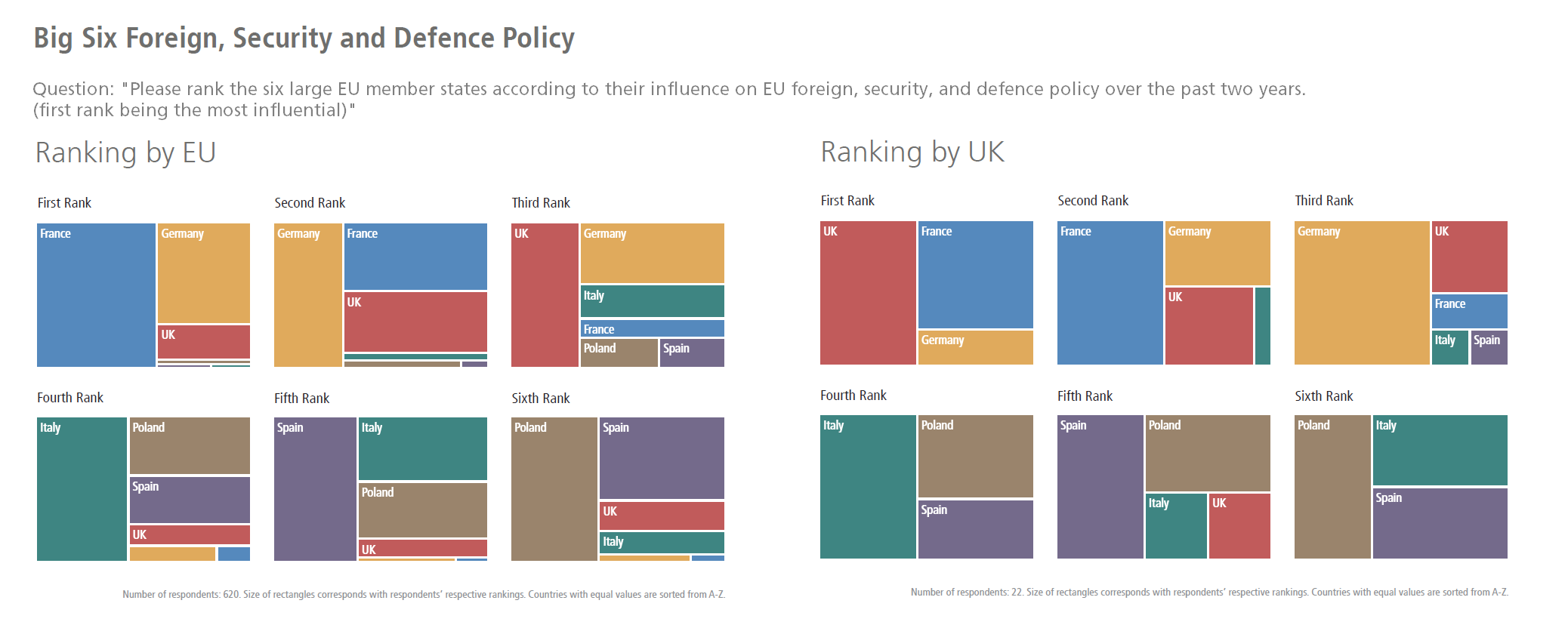

What do EU member states make of this situation? ECFR’s EU Coalition Explorer shows that they continue to perceive the UK as influential in foreign, security, and defence policy. Yet the study also shows that London has slipped on these fronts since 2016. Moreover, it reveals that the UK continues to view itself as being the most influential country in these domains. This is a bold self-assessment, implying a somewhat misguided Brexit bravado.

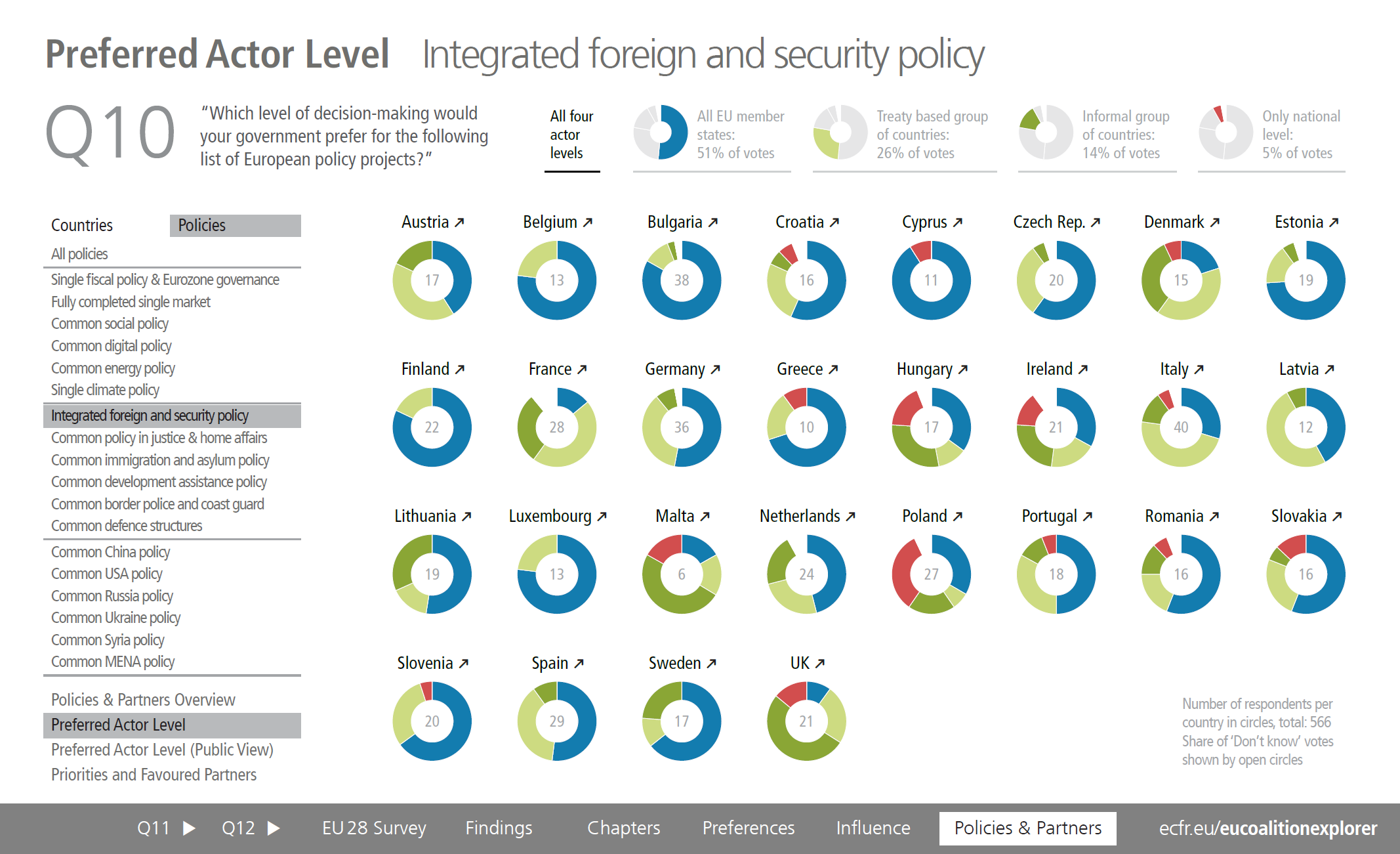

The EU Coalition Explorer also reveals that the UK would prefer to engage in these areas through bilateral and coalition structures. In reality, the challenge for the country will come when it finds itself as a third party, grappling to make existing and emerging EU structures work for it. The EU and its member states are engaged in a process of moving – however shakily – towards greater strategic autonomy. In doing so, they are rethinking the foundations and practicalities of their relations with third countries and testing out “multi-speed” forms of flexible policy- and decision-making. In theory, at least, both tracks could provide mutual benefits for both the UK and the EU. But how likely are the sides to find a way forward together?

Firstly, in terms of the UK continuing to work through EU structures, the jury remains very much out. The UK is unlikely to gain privileged access: it will have to rely on the flexibility of the Commission and the will of EU member states for future invitations and opportunities to play any meaningful role in EU-led foreign, security, and defence initiatives. It is likely that the EU’s current efforts to step up, for example, its Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and new initiatives such as Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Defence Fund, are just some of the enterprises that will benefit from greater insulation from the UK’s sometimes disruptive behaviour – especially its oft-used veto on EU security matters.

At present, there is not even an outline of the types of activity the UK may be able to partner on, nor of the decision-making processes that would allow this to happen. Will it, for instance, be able to join CSDP/PESCO missions? And how exceptional might cases have to be for such invitations to come? Will the UK have to settle for a more consultative role – like Norway’s – or will it be granted greater active control? Will the EU’s defence ambitions undermine the UK’s? And will the country still have access to sensitive information and data-sharing systems?

Worryingly, there is a cautionary tale for this type of cooperation. The UK and the EU have already butted heads over the Galileo satellite project during the Brexit process: the UK rejected the EU’s offer of restricted access to the initiative. This should serve as a stark reminder for both parties of the potential difficulties of cooperation in the years ahead.

Outside EU structures, however, there are glimpses of a brighter future for UK involvement in the wider European theatre. Despite ongoing challenges within NATO, the UK is still highly committed to the alliance and remains at the forefront of its eastern European Enhanced Forward Presence programme. Transatlantic divergences and the energy-sapping nature of Brexit mean that the UK will likely struggle to bridge gaps between the United States, the EU, and NATO. But its “lead nation” status within the organisation is not going change any time soon, meaning it will remain a crucial player in transatlantic security cooperation.

The UK’s Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF) with France is also maturing, offering greater interoperability and coherence between sea, land, and air forces, and greatly increasing the speed, flexibility, and effectiveness of military deployments. Add to that the historically interventionist tendencies of the UK and France, along with their similar geopolitical interests, and the importance for both countries of meeting the 2020 target for CJEF operability appears clear. Indeed, given that the UK is already well set up to work closely with its neighbour across the Channel, France will shortly become a strong ally for the country within the EU. In Britain, this may allay fears about the emergence of a Franco-German axis that dominates EU foreign policy. Franco-German shared interests remain strong, and despite differences over new EU-level initiatives such as PESCO, the fact remains that little is known about whether and how the UK will eventually become involved in such arenas. Consequently, a strong bilateral UK-France partnership will, in British eyes, likely provide a suitable counterbalance.

In a similar vein, the UK will also have the option of further turning towards its Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF). This involves a small constellation of like-minded northern European and Baltic states, including the Netherlands and Estonia, as well as two non-NATO states, Sweden and Finland. EU Coalition Explorer data show a close alignment of interests between JEF countries. Here again, greater interoperability and flexibility – given the case-by-case, voluntary nature of the JEF coalition – should provide the UK with a ready-made platform for further coalition-building.

Ultimately, much will depend on the trajectory and final outcome of Brexit – especially in the short term. In recent months, the chances of both a no deal exit and a second referendum have risen, increasing uncertainty and further exposing key divisions between the UK and the EU on the way forward. And – while there is certainly some merit in understanding foreign, security, and defence policy as “special cases” in the realm of high politics – it is presumptuous for the UK to assume that these issues will transcend the inevitable fallout from Brexit, whatever form it eventually takes. Building coalitions beyond the confines of EU structures may increasingly appear to be an attractive option for the UK in particular as it casts around for new possibilities. Doing this without shutting itself off from potential future participation in new and existing EU structures will not be an easy tightrope to walk – not least with the wider economic ramifications of Brexit likely to spill over into other aspects of relations. EU Coalition Explorer research showing that the UK still regards itself as highly esteemed should be a warning for the country to dial down the bravado and listen closely.

About the author: Euan Carss is currently an Economic and Social Research Council funded Ph.D. candidate at King's College London. He has been an ECFR associate researcher since Autumn 2018.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. Several hundred respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualisation, the EU Coalition Explorer, are available online at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU that is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.