Belgium’s integration blues

Growing tensions on the left and the right have driven the country to adapt a more cautious stance towards European matters

At first glance, the latest edition of ECFR’s EU Coalition Explorer confirms the widespread perception that Belgium has outsized foreign policy influence. Compared with countries that have economies and populations of a similar size, Belgium has consistently ranked above average in its capacity to shape international affairs, remaining one of the ten most influential states in the European Union. However, as all Spiderman fans know, with great power comes great responsibility: if it is to maintain this privileged position, Belgium must carefully manage its internal divisions.

The task may become considerably harder following the country’s 2019 federal and regional elections. Due to tension on the left and the right, the traditional Belgian consensus on European policy is deteriorating – as two recent events suggest. The first of these incidents is the Walloon Parliament’s October 2016 decision to temporarily block the signing of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). The move surprised Belgium’s traditional partners and put its credibility at risk. Only a last-minute compromise on the issue prevented severe damage to the country’s perceived reliability in Europe, and even beyond. Indeed, Belgium endangered its international reputation as an honest broker that is able to forge a consensus.

The ensuing rise of Paul Magnette – who, as minister-president of Wallonia, came to symbolise the struggle over CETA – reflected the growing popularity of leftist anti-globalisation rhetoric. This trend, also seen in the far left’s gains in local elections in Wallonia in 2018, has led Belgium’s French-speaking socialist party to harden its positions. As the party remains the largest political force in the region, the formation of the next federal government will likely be challenging. This especially true given that Flemish parties increasingly lean to the right, due to the growing influence of the nationalist New Flemish Alliance (NVA).

Nationalist groups changed Belgium’s political agenda, particularly on EU affairs

The NVA was at the heart of the second recent crisis in Belgium’s international credibility. In the aftermath of the 2017 Catalan independence referendum, separatist leader Carles Puigdemont fled to Belgium. Although he claimed not to have received a formal invitation, Puigdemont’s well-known ties to the NVA led to speculation that he had reached an arrangement with Flemish nationalists. The ensuing politico-judicial imbroglio around Madrid’s request to extradite him to Spain put the Belgian prime minister in a very difficult position and raised questions about the coherence of Belgium’s European policy.

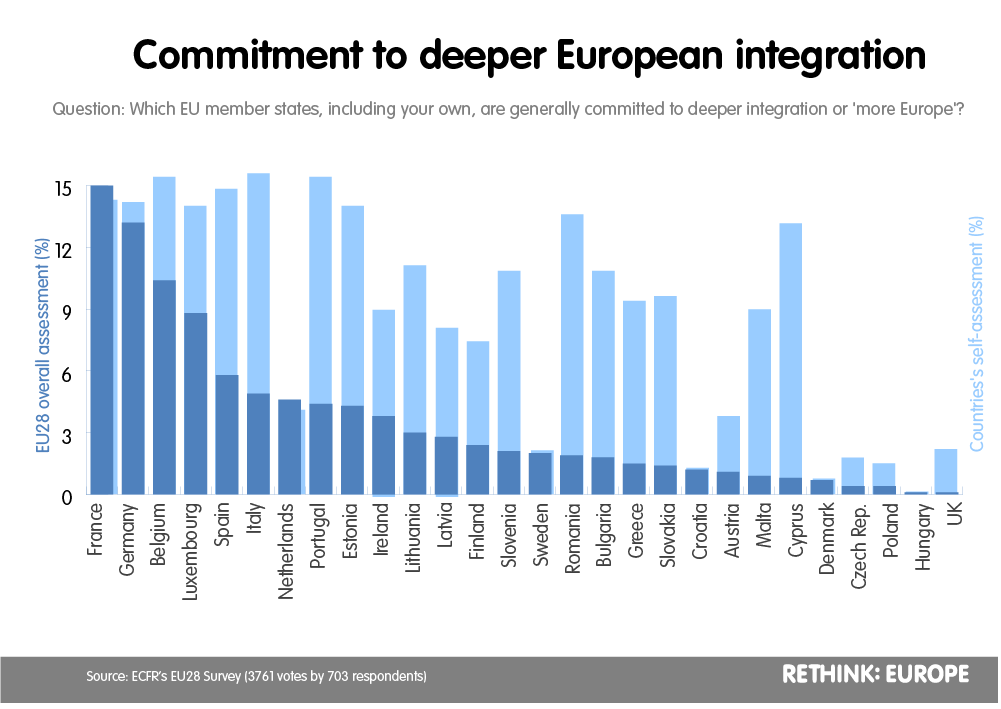

The controversy also demonstrated the political power the NVA has acquired since the 2014 elections. While nationalist groups operated discretely in the federal parliament until 2017, they considerably changed Belgium’s political agenda, particularly on European matters. Adopting an increasingly critical stance on the European project (without becoming fully Eurosceptic), the party openly challenged a traditional point of consensus in Belgian foreign policy: the need for ever closer union. Interestingly, other European countries appear to have largely missed this shift. As the EU Coalition Explorer shows, Belgium’s European partners continue to see the country as more committed to deeper integration than all but two other member states.

Yet the rise of the NVA is not the only factor in this shift in attitude. The numerous sources of opposition to European integration within the EU have led Belgian officials to adopt a more nuanced attitude towards European affairs. For example, Prime Minister Charles Michel is becoming ever more supportive of differentiated integration. In this context, the intensified Franco-Belgian cooperation shown in the Coalition Explorer’s data should come as no surprise. Michel and French President Emmanuel Macron are both committed Europeans who believe that the EU can be strengthened through the creation of a more integrated “core” of member states.

ECFR’s study also reveals that Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg still seem to share many preferences in European policy. However, the importance of this grouping should not be overestimated: according to the Coalition Explorer, Belgian officials are more willing to interact with France than the Netherlands or Luxembourg. This is due not only to pragmatism but also to the influence of rivalry between Walloon and Flemish parties on Belgian foreign policy. Some French-speaking Belgian officials claim to have sought France’s support out of concern over increased “Dutch influence”. Thus, Belgium – one of the driving forces of European integration – finds itself in the same situation as the union it helped shape: mired in internal divisions between its constituencies and secretly praying that it can avoid implosion in the next round of elections.

Simon Desplanque is a PhD candidate at Belgium’s Université Catholique de Louvain. His research focuses on the relationship between culture and international affairs, as well as the history of US foreign policy. He is also interested in Belgian foreign policy. Simon has been an associate researcher at ECFR since 2015

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. Several hunded respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualisation, the EU Coalition Explorer, are available online at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU that is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.