Austria’s toughest EU presidency

Although Austria has the potential to influence EU policymaking more, the country often stands in its own way.

On 31 December 2018, Austria completed its most consequential term as president of the Council of the European Union. Throughout its six-month tenure, Vienna faced greater challenges and upheavals in Europe and beyond – not least complex negotiations on the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU and on the next Multiannual Financial Framework – than it had during either of its previous stints in the role, in 1998 and 2006. With Romania having taken over the presidency in January, it is now possible to answer several key questions about the Austrian presidency. Firstly, was the country sufficiently engaged with its responsibilities? And, secondly, how has the presidency affected Austria’s attempts to build coalitions with its peers?

As president, Austria prioritised security and the fight against illegal migration; stability in Europe’s neighbourhood; prosperity and competitiveness through digitalisation; and the EU perspective of countries in the Western Balkans. Vienna pushed to bring the EU closer to its citizens, re-establish trust between member states, and improve the Union’s ability to act effectively in a range of policy areas. It proved that it could achieve some of the targets it set for itself and work on common solutions with its partners by acting as an honest broker between them. For example, Vienna contributed to the unification of the EU27’s position on Brexit early on and the adoption of the Withdrawal Agreement and the Political Declaration on the future UK-EU relationship in November 2018.

The momentum Austria has gained through the presidency could soon be lost

Taking up the motto “a Europe that protects”, Austria called for the EU to shift the focus of its much-disputed migration policy away from relocation within the Union and towards border protection, repatriation, and countering people smugglers. This involved intensive work on external border management (which resulted in a strengthened FRONTEX), internal asylum system reform, and enhanced cooperation with African states. In all, there were around 2,700 meetings, 53 political agreements with the European Parliament (EP), and 75 agreements in the Council – while the EU adopted 56 conclusions and recommendations, and the Council and the EP signed 52 acts – during Austria’s presidency.

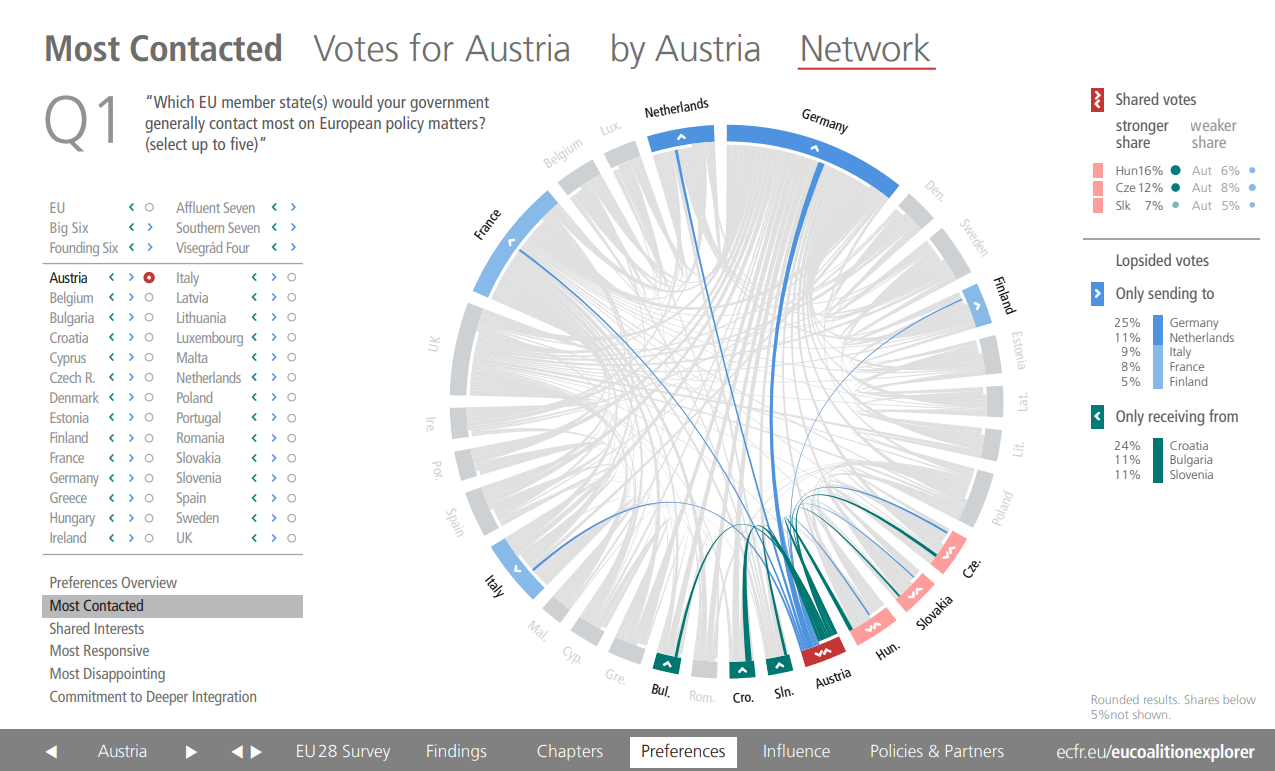

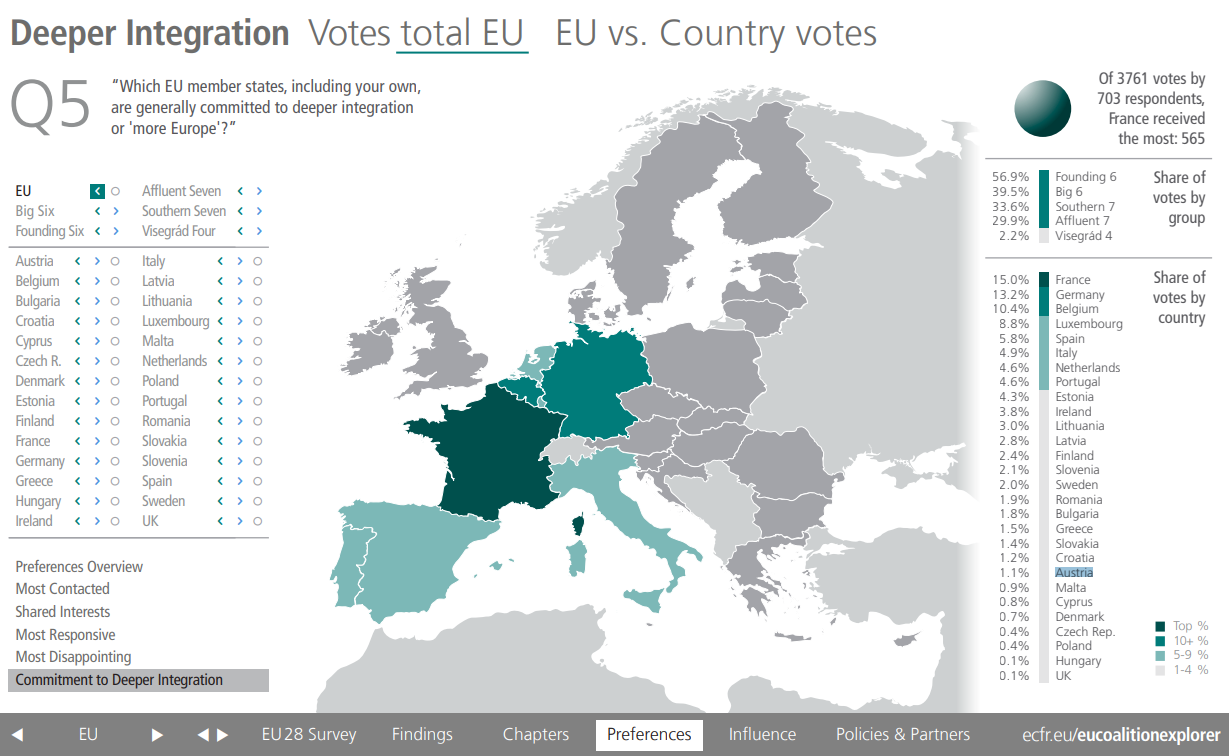

The country’s contribution to these efforts may be even more impressive in light of its traditional conservatism, neutrality, and lack of influence in the EU. Indeed, in ECFR’s 2018 EU Coalition Explorer, Austria ranks in 21st place in its commitment to European integration, while most member states do not regard it as an essential partner on European policy matters. Selecting from up to five EU countries, respondents viewed Austria as the tenth most influential member state, lagging behind the Netherlands, Sweden, and Belgium – which, together with Finland, Denmark, and Luxemburg, make up the so-called affluent group. (This group has significant economic clout because its combined GDP is higher than that of France and its constituents all maintain an employment ratio of at least 11 to 1.) In contrast, almost 21 percent of respondents’ votes indicated that EU28 governments first turn to Germany in dealing with European policy issues, while almost 14 percent of all votes indicated that they first turn to France.

Austria clearly has asymmetrical and often difficult relationships with other EU countries, especially Germany – not least because of Vienna’s approach to migration policy. As much as Austria looks to Germany (which received 25 percent of Austrian votes), Germany rarely looks to Austria. The same pattern is evident in Austria’s relationships with France and Italy (see graphic above). One – slightly simplified – explanation of this is that Austria misperceives itself as one of the EU’s big players. In consultations on European policy matters, relatively small countries such as Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Croatia turn to Vienna more often than Berlin does. Due to their economic links – as well as their nostalgia for a shared imperial history – Vienna seeks relatively close interaction with Budapest and Prague, which receive six percent and eight percent of Austrian votes respectively. From Austria’s point of view, this largely leaves countries such as Slovenia, Croatia, and Poland on the sidelines. Now – following a six-month presidency during which Austria had a chance to actively participate in shaping the EU – it seems possible that the country’s coalition-building efforts will grow and bear fruit.

Lessons of the presidency

Austria has been preoccupied with itself due to a degree of domestic unrest – which most citizens would blame on the fact that the governing coalition includes the right-wing Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ). This introspection prevents the country from fulfilling its potential in European matters.

Nonetheless, Austria breathed new life into the policy areas it prioritised as president, devoting much attention to improving the EU’s strategic communication. It is important for the country to maintain its focus on these issues even after it has completed its presidency, developing new initiatives and making its voice heard among other member states. It is also crucial that Austria builds on its experience as an honest broker and puts more effort into finding common ground, and building fruitful coalitions, with other member states. Otherwise, the momentum the country has gained could soon be lost.

Sofia Maria Satanakis has been a research fellow at the AIES since 2013. Her research covers the topic of European Integration, with a special focus on the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP).

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. Several hundred respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualisation, the EU Coalition Explorer, are available online at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU that is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.