After the European Parliament election: Another chance to bridge Europe’s divides

The recent European Parliamentary elections revealed that there is more to Europe's political geography than the traditional east-west divide

As tempting as it may be to simply divide Europe into east and west, the recent European Parliament election demonstrated that reality doesn’t quite work that way. Take Hungary and Poland, two of the leading rebels against the status quo in Brussels: as expected, the election produced even bigger majorities for Fidesz and the Law and Justice party (PiS), led by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and Polish politician Jaroslaw Kaczynski respectively. But the vote failed to divide the pan-European centre-right, which may now bring Fidesz and PiS back into the fold (as far as is possible).

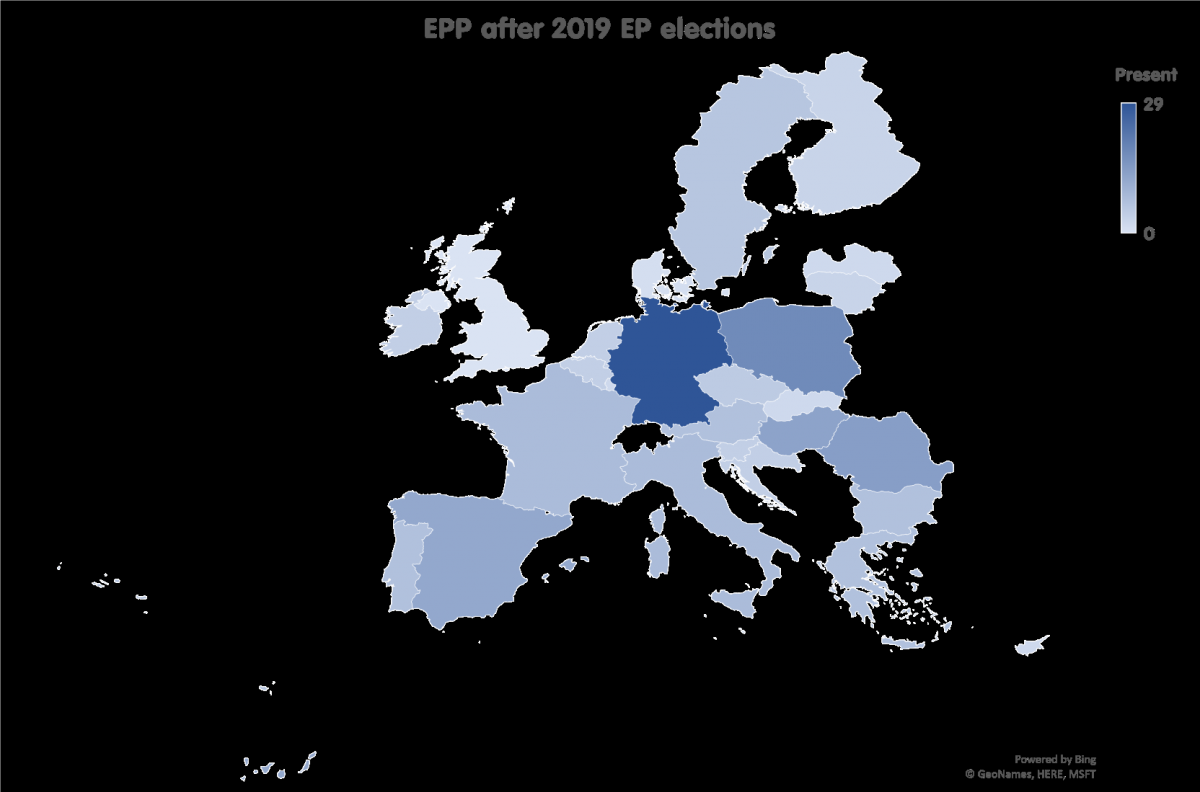

The first channel of calibrated communication between the sides will be the European People’s Party (EPP), in which Fidesz is suspended but still a member. However, in the election, this mainstream political group – traditionally the largest in the European Parliament – underwent a twofold transformation. The EPP lost 37 seats (bringing its total to 179) and became more eastern European in its composition, albeit with Germany remaining its biggest source of members of parliament. The grouping’s vote share declined in Italy and France, but increased in Austria, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Romania, and Sweden. Currently, the EPP members in the European Council are the leaders of Bulgaria, Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, and Latvia (as well as Austria, which has a caretaker government). In the ongoing negotiations over the European Union’s five top jobs, Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovič and his Latvian counterpart, Arturs Krišjānis Kariņš, represent the EPP.

There have also been geographic shifts in other pan-European political families. The Socialists and Democrats became more southern, making their biggest gains in Spain and Portugal, while the Liberals became more western – and are now represented by a predominantly French group in the European Parliament, with Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte and his Belgian counterpart, Charles Michel, sitting next to French President Emmanuel Macron in the European Council.

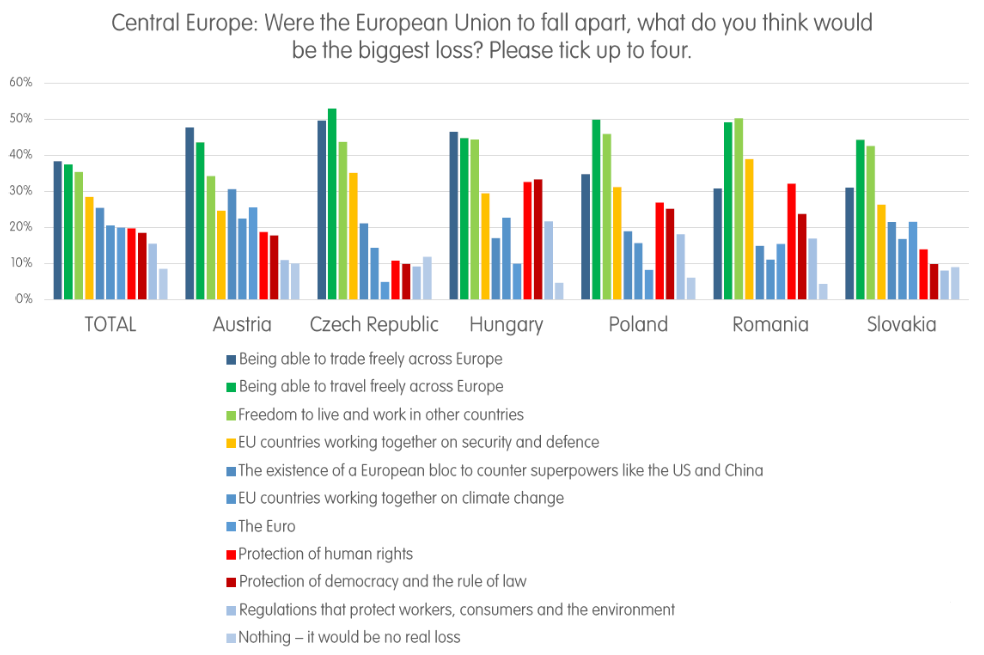

This more eastern EPP could try to tame the rebels in central and eastern Europe, especially on trade and cooperation on security and defence. In the European Council on Foreign Relations’ Unlock survey, central and eastern European voters clearly indicated that these are the main issues for which they value the EU. Reaching across the aisle to soft Eurosceptics in the European Conservatives and Reformists grouping (which includes PiS) on these topics would pull them away from the far-right camp of Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini, Rassemblement National leader Marine Le Pen, and Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage.

Negotiations over the Multiannual Financial Framework, the EU’s budget for the next seven years, have already stared. These talks will involve the big battles over the size of the budget and the conditions attached to cohesion policy, the tool for transferring funds to relatively poor countries and regions of the EU. Member states will have to find a compromise between net contributors and net beneficiaries.

While they will probably be aligned on the size of the budget, central and eastern European countries will likely remain split on the rule of law conditions attached to the funds they receive. Some – such as the Baltic states, Bulgaria, Croatia, and Slovenia – seem prepared to agree to stricter conditions, while the Visegrád group (comprising the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) will oppose them. These internal divides make negotiations more complicated, but also provide an opportunity to drive a wedge between members of the far-right camp. When the moment for political grandstanding and highfalutin rhetoric passes, the negotiations come down to what politicians can deliver for their constituencies.

Efforts to divide the far right require more tact and open-mindedness from Macron, who has clearly positioned himself as the antipode of Orbán. The EU risks being torn apart by a civil war between its liberal and authoritarian democracies – as the French president warned before the election. (His attempt to polarise France worked, as he practically eliminated the country’s established centre-left and centre-right parties in the European Parliament election.) A more conciliatory French stance towards Europe’s east will be a precondition of a differentiated and inclusive conversation about ways to reinvent Europe in the next parliament. Gaining France’s support will also be one of Germany’s primary interests in the negotiations.

Along with security and defence, central and eastern Europeans have two other key areas of concern. The belief that the EU treats post-2004 accession states as second-class citizens and fails to take them seriously is a major factor in the appeal of Eurosceptics. The reasons for this belief range from differences in pay to quality of food, to a lack of understanding of one another’s views. The underlying dynamic of this is what historian Tony Judt calls the “politics of aggrieved memories”.

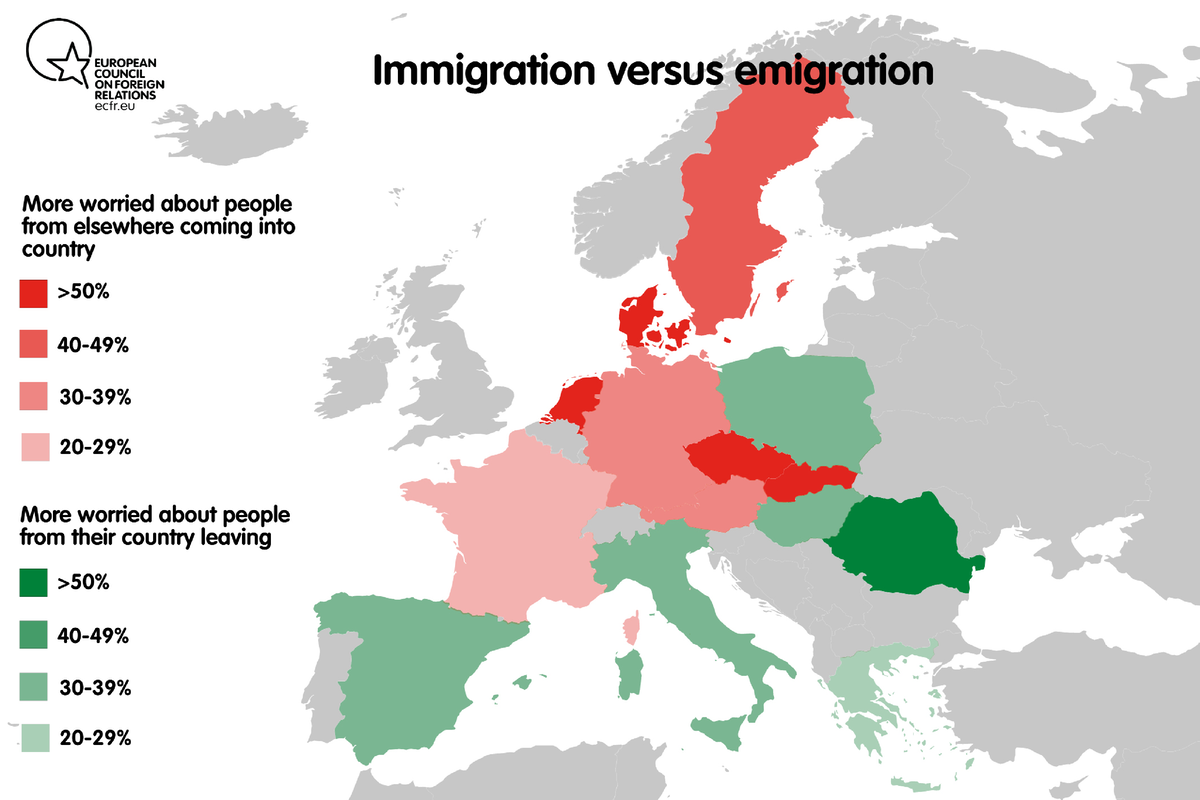

More tangibly (and thus more practically manageable), people in eastern and southern Europe view emigration as more worrying than immigration. If the map below covered the Baltic states and the western Balkans, one would see that they conform to this trend – as several pieces of research in these countries show. Eastern and southern Europeans’ fear that the economically powerful northwest draws people, resources, and ideas away from them has become a major political force. Moreover, as current cohesion policies fail to address the issue effectively, they will need to be customised – especially in supporting healthcare and educational systems in net contributor countries.

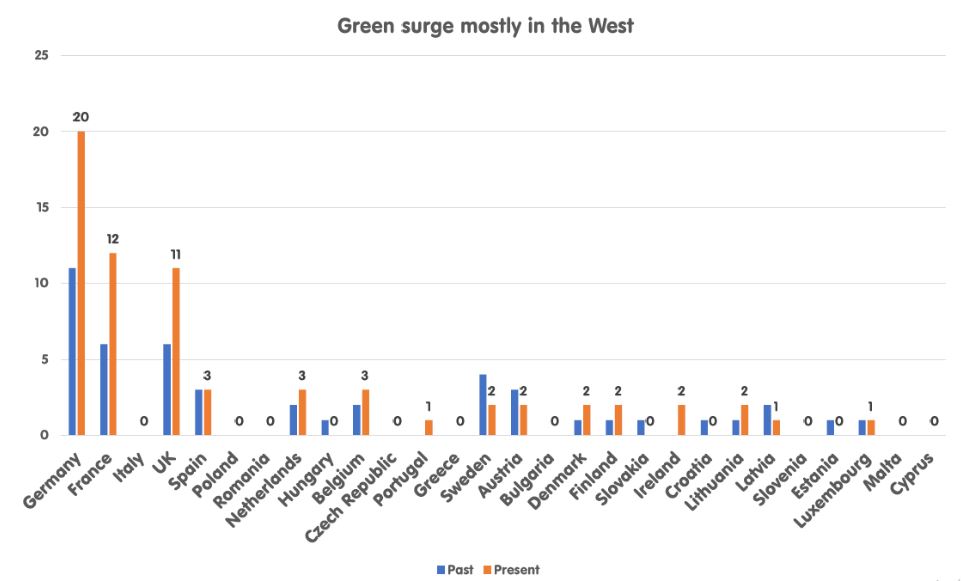

Large-scale emigration and an ageing population make for a toxic mixture. “We lose our people, which is why we cannot afford to worry about ‘luxury’ topics like [the] environment”, one Bulgarian sociologist recently observed. Indeed, the Green surge in the European Parliament election took place in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom; in the east, the topic is rarely discussed. This has to do with the belief that catching up with western Europe economically takes priority over environmental concerns – another consideration that is important to improving EU cohesion.

A central or eastern European appointee in one of the EU’s top jobs is necessary to bridging some of Europe’s largest internal divides. But this has one caveat: the position of high representative for foreign affairs and security policy would not be sufficient, as the belief that European foreign policy is mainly driven by big western European countries has taken root in central and eastern Europe. Thus, such an appointment would lend little credibility to the gesture.

Much will depend on the final outcome of the negotiations and the appointments process. Unless it creates a fundament on which a new vision for Europe can flourish, the EU will continue to disintegrate into different classes of member states. What more important task is there, 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall?

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.