A united front: How the US and the EU can move beyond trade tensions to counter China

The Inflation Reduction Act may reduce US dependency on China, but it also risks harming the transatlantic relationship. European governments must position themselves as critical allies for the US in order to preserve their economies – and effectively counter China’s geo-economic challenge

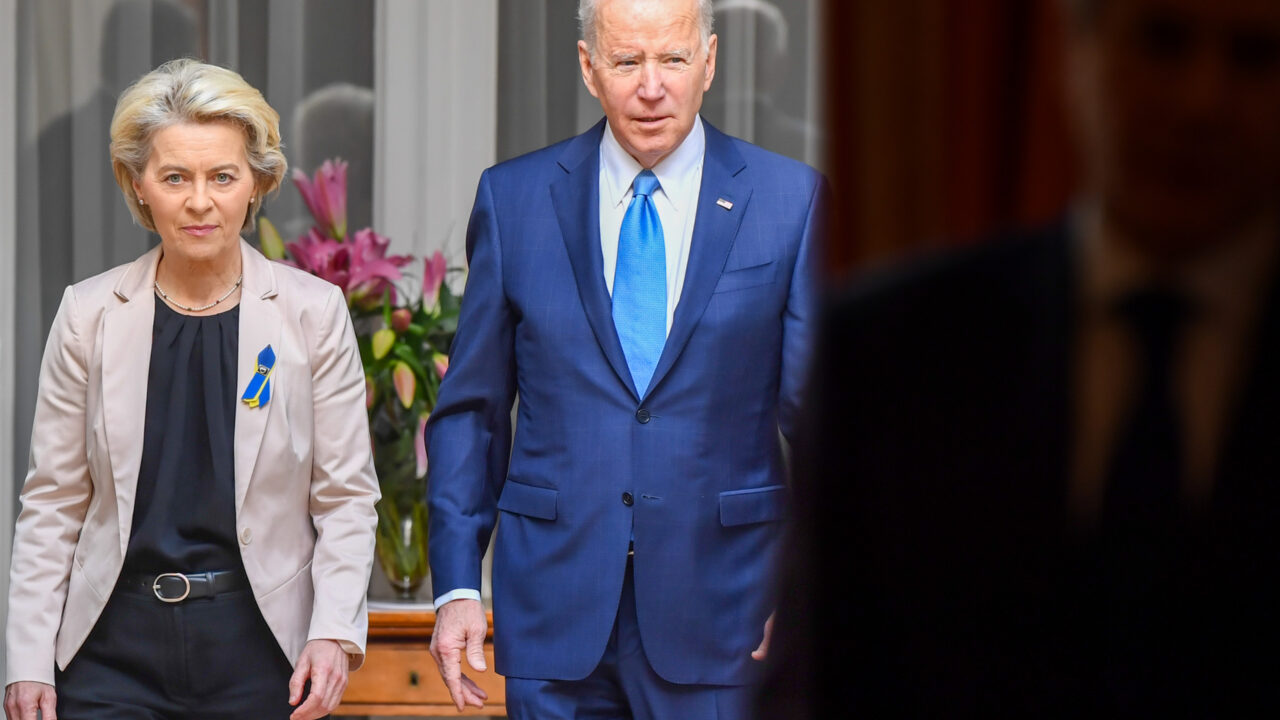

In August 2022, President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) into law. The IRA is America’s most significant climate legislation ever. It makes available some $737 billion in public funding, $369 billion of which in subsidies, to promote US-made clean energy technologies such as electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries, hydrogen, energy storage, and electricity transmission, and to diversify these supply chains away from China. The bill promotes climate goals that European governments generally share, but it also demands that products be assembled in the United States to qualify for tax credits – provisions which likely discriminate against European exporters. Several European clean energy companies have already indicated their interest to shift investments to the US, raising the risk that the law could accelerate the process of deindustrialisation in Europe. President Emmanuel Macron’s trip to Washington, DC at the beginning of December was a last-minute attempt to secure exemptions for European countries from the IRA’s more discriminatory provisions. Biden promised tweaks to the bill to ease the negative consequences for the European Union, but the details remain unclear. More importantly, bickering over this bill may obscure the bigger issue of how to ensure the health of the transatlantic relationship in the face of China’s geo-economic challenge.

The deeper meaning of the IRA

A clear bipartisan consensus has emerged in Washington on the need to restructure the US economy away from reliance on China and towards a new form of strategic economic nationalism. The goal is to revitalise the American economy, and in doing so position it to prevail in the geo-economic struggle with China. European countries are not the target of this effort, but they risk becoming collateral damage if they cannot position themselves as vital allies in the US effort to compete with China. The IRA, with its “made-in-America” provision, aims to boost manufacturing in the US. The bill mandates that, to qualify for IRA subsidies, EV products must be assembled in north America – 50 per cent of the final product calculated according to its value at first, subsequently increasing by 10 per cent every year after the bill is implemented.

Along the same lines, one of the key objectives of the IRA is to exclude Chinese suppliers from clean energy supply chains. Currently, China dominates much of that value chain, including some 75 per cent of global production of battery cells and 85 per cent of all solar photovoltaic cells. Seven out of the top ten wind turbine producers are also Chinese companies.

The reshoring effort is part of America’s strategic rivalry with China. With the IRA, Biden promised to give America “the ability not only to compete with China for the future, but to lead the world and win the economic competition of the 21st century”. To do so, the US is focusing on strengthening industries and technologies that are key to the United States’ future national and economic security. For example, the CHIPS Act, also passed in August 2022, provides $52.7 billion in subsidies for semiconductor research, development, and manufacturing in the US. This has already resulted in the Taiwanese semiconductor company TSMC as well as the American companies Intel, Micron, and IBM announcing investments totalling close to $200 billion in the US.

The EU’s response

The EU’s immediate response to the IRA has focused on seeking exemptions from the discriminatory clauses. It has attempted to do so by using the threat of a counter-subsidy package as leverage, while accusing America of betrayal and even war-profiteering. This approach is not likely to be effective. Accusing the US will further antagonise Washington, which has contributed disproportionally to fighting the war on the EU’s borders. Meanwhile, the threat of a counter-subsidy package lacks credibility; it would risk pushing both sides into a race to the bottom as companies could threaten to move overseas unless they receive ever higher subsidies. Many more liberal EU member states, including the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland, oppose such a package on free trade grounds and the US will probably be able to rally the central European member states against it by reminding them of the United States’ role in their defence.

There is also the option to sue the US in the World Trade Organization (WTO), but this would take a long time and would be unlikely to produce results, given that the US is currently blocking appointments to the WTO appellate body – which is responsible for reviewing appeals – and challenging or ignoring its rulings.

A better approach

The EU would be wiser to focus on what actually matters to the US: China. It should deliver a clear and simple message that the IRA makes it more costly and less likely for EU states to align with the US on China. The US cannot afford to lose Europe if it wants to prevail in its economic rivalry with China. US efforts to stop technology transfers to China, for example, will only be effective in the long run if the EU plays along. Beijing is aware of this and has already used the IRA as an invitation to Europeans to continue to rely on Chinese clean energy supply chains.

Similarly, transatlantic cooperation on clean energy is probably the only way for either side to end its reliance on China. Like those in the US, Europe’s clean energy supply chains are already dangerously dependent on China. China could become the biggest battery manufacturer in Europe within a decade, analysts suggest, dominating the most valuable part of the EV production chain. China’s EV companies have begun a broader export offensive in the European market, and China’s export of EVs to the EU could soon be larger than all car exports from the EU to China. Targeting these dependencies is in the EU’s economic interests and could help convince Washington that Europe is a necessary and useful partner on China.

The US must refrain from further tilting the playing field in its trading relationship with the EU and the EU must demonstrate to the US why it is worth doing so.

As a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, transatlantic trade and investments have boomed. Between September 2021 and September 2022, Germany’s exports to the US rose by 50 per cent. Trade in goods and services across the Atlantic is over 40 per cent higher than that between the EU and China. Finally, EU investments in the US in 2019 were ten times larger than EU investments in China, and the EU has attracted over 60 per cent of all American foreign direct investment in the past decade. To maintain this positive momentum, the US must refrain from further tilting the playing field in its trading relationship with the EU and the EU must demonstrate to the US why it is worth doing so.

The prospect of the Republicans coming back to power in 2025 makes this task all the more urgent. Any future Republican administration will be yet more transactional in its relationship with the EU and will make its trade policies vis-à-vis Europe dependent on the EU’s strategic industrial policy on China.

Any industrial strategy response to the IRA by Europe should clearly highlight the China factor. European decision-makers need to confront the reality that lies beyond the immediate IRA challenge: the health of the transatlantic relationship will hinge ever more on Europeans’ willingness to work with the US to confront China’s geo-economic challenge. Both sides will lose if they do not find a solution to the China trade-security conundrum. The US policy on China is unlikely to yield the desired outcomes without close alignment with Europe. European governments need to make clear to the US that refraining from protectionist measures towards allies will be critical to attaining that alignment.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.