A fundamental fight: The frugal four and the rule of law

The ‘frugal four’ are showing an admirable commitment to defending the rule of law. But they bear some responsibility in Hungary and Poland

On the day Hungary and Poland vetoed the European Union’s multiannual budget and coronavirus recovery fund, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte had a session in parliament in The Hague. Rutte refused to water down the new rule of law conditions that prompted the veto. The compromise deal was already the “lower limit”, he said.

When a far-right Dutch MP said Rutte didn’t have half the guts of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Rutte replied: “Should I limit gay rights, limit freedom of the press in the Netherlands, and limit the rights of smaller parties to participate in elections? I am glad I am not like him. Terrible.”

Rutte is not the only northern European leader losing patience with Poland and Hungary. Sources report that Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen clashed with Orbán during the October European Council meeting, at which he opposed the words “gender equality” in a text because of its ‘ideological’ implications. Austria’s Europe minister, too, has taken issue with the two countries’ veto.

The Europe of rules, principles, and procedures is clashing head-on with the political Europe of strongmen who use raw power and codes of honour.

It is good that the EU member states widely known as the ‘frugal four’ are committed to defending the rule of law in Europe. It shouldn’t be forgotten, however, that they also bear some responsibility for the fact that the EU has done little to halt the continuous deterioration of the rule of law in Hungary and Poland in recent years.

For many reasons, member states have long turned a blind eye to the situation. They are always reluctant to sanction one another on any given issue – the Stability and Growth Pact comes to mind. Moreover, the erosion of independent institutions in Poland and Hungary was a slow process. At every stage, party-political sensitivity and tactical disagreements about the timing and the ‘right’ way to address the problem in Warsaw and Budapest played a role. Finally, member states have had to stamp out some big fires in recent years – the euro crisis, the refugee crisis, and Brexit. Many thought this was not the time to start internal battles over European values.

But now the chickens have come home to roost. Ten years of accumulated irritation are erupting. The Europe of rules, principles, and procedures is clashing head-on with the political Europe of strongmen who use raw power and codes of honour. It is a dirty but fundamental fight.

In the Polish parliament last week, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki compared the EU to the old communist regime. The “European oligarchy”, he said, violated the rule of law itself by attacking his country. He said that Poland, a major recipient of EU funding, would be “better off” without the bloc’s multiannual budget. This was the most anti-European speech by a Polish Prime Minister ever.

On the other side of the debate, there are European leaders who have become outspoken about the rule of law – such as Rutte. Until recently, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Austria, and Finland mainly took issue with southern countries, and mostly about money. Now, they have a new common theme: the rule of law.

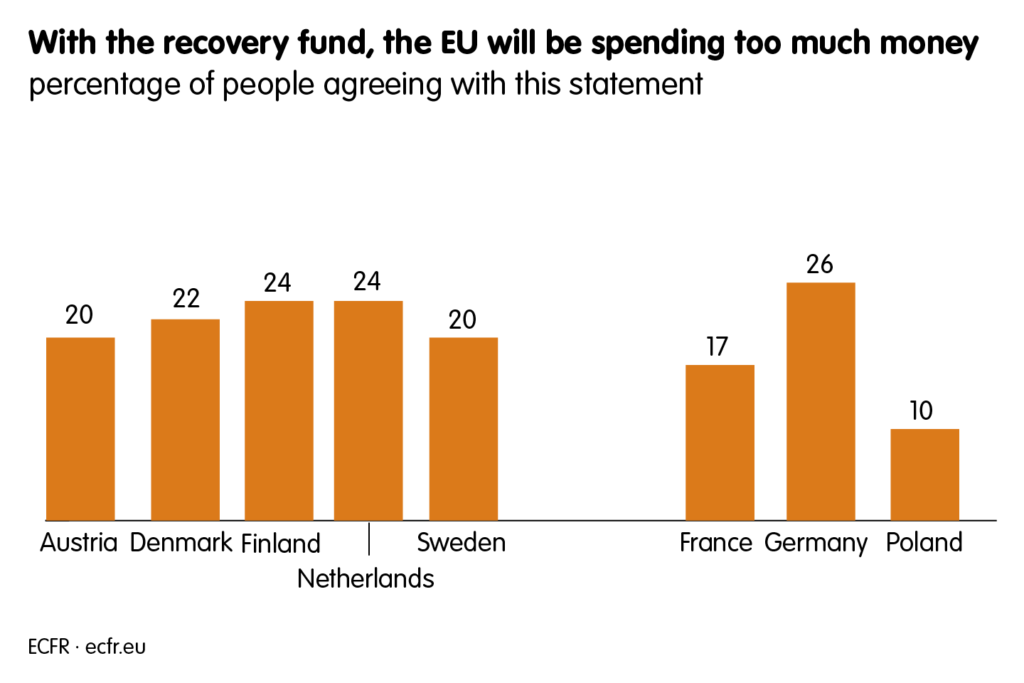

Polls published by ECFR on Wednesday show that the main problem citizens in those five countries have with the new EU budget and the coronavirus fund is not that the bloc is spending too much money. No, their greatest concerns are waste and corruption. Twenty per cent of Austrians worry about the amount of money spent on the fund, and 48 percent about waste and corruption. In the Netherlands, these figures are 24 per cent and 38 per cent respectively. It is interesting to note that respondents in Germany, France, and even Poland itself have the same priorities. No one should be surprised if, in the coming months, European debates increasingly focus on the rule of law. With a Dutch parliamentary election scheduled for March 2021, Rutte plays this well.

Yet it wasn’t the frugals who linked the disbursement of European funds to rule of law requirements. Credit for that goes to the European Parliament. In July, the frugal countries managed to limit European spending, but failed to condition it on the rule of law. In autumn, member states reworked the July deal into a European draft bill. When this draft arrived in the European Parliament, it contained the usual corruption and fraud clauses – but nothing about the rule of law. MEPs then inserted provisions on an independent judiciary, for example. Intense negotiations followed. Member states eventually watered down this version. Finally, they reached a compromise with the European Parliament. Poland and Hungary objected to the rule of law mechanism, but were outvoted. They then decided to veto the entire budget and the coronavirus recovery fund, which require unanimity.

There is a second reason why the strong stance on the rule of law in some northern European capitals sounds a bit hollow. Member states could have brought cases against Poland and Hungary before the European Court of Justice. They could also have provided stronger backing for the cases eventually filed by the European Parliament and the European Commission. They did not. As a result, there is now a risk that those cases will peter out. Furthermore, member states could have used EU funds to give the new European Public Prosecutor more teeth in the fight against corruption. Instead, they gave her a small budget and very little power: she is totally dependent on the goodwill of national courts. Sweden and Denmark are not even engaging with the EU prosecutor. Finally, plans to strengthen Europol’s powers in the fight against corruption have also met with opposition from many member states.

Some have observed that the embrace of the ‘frugal’ banner is becoming a trap for countries such as Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands. They think it is good if these countries also become positively engaged in Europe by taking a strong stand on rule of law issues.

But there are risks, too. It could even reignite disputes between north and south. Southern European countries are becoming nervous about the standoff over the rule of law: so long as it lasts, there will be no coronavirus recovery fund – of which they will be the largest recipients. They have not forgotten that, initially, the frugal countries were against this fund. And they felt hurt by some frank remarks from the Dutch minister of finance. In this context, some in Italy and Spain now suspect that, by refusing a compromise with Hungary and Poland on the rule of law, northern European countries are killing off the fund, too.

No one knows who will blink first. The issue is now completely politicised, and the linkage to other problems makes this nut all the harder to crack.

In a long letter to European Council President Charles Michel, Orbán wrote that he would only revoke his veto if every link between European subsidies and the rule of law disappeared. He signed off quoting Luther: “Hier stehe ich. Ich kann nicht anders.”

Caroline de Gruyter is a Council Member of ECFR, and a European Affairs columnist and correspondent of the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad. This article was adapted from a recent column in NRC.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.