Don’t close borders, manage them: how to improve EU policy on migration through Libya

Summary

- Two years after the start of the refugee crisis, migration flows via Libya to Europe are increasing, while deaths in the Mediterranean have skyrocketed. Current policies have failed to reduce the number of migrants reaching Europe’s shores.

- The EU and its member states need to rethink their basic assumptions about migration and break popular taboos about the movement of people if they are going to reduce flows. The first step is to cast away the idea that borders can be completely closed to economic migrants.

- The EU and its member states need to manage flows, rather than aiming to cut them to zero. To do this, legal migration channels should be opened so that illegal channels can be shut via a series of readmission agreements.

- Through a coalition of the willing, EU member states can implement this policy, which should also involve establishing safe and quick procedures to guarantee asylum to refugees; reinforcing the Libyan economy and its local communities; building respect for the rule of law and human rights; and finally, broadening the scope of the EU Border Assistance Mission to Libya.

Policy recommendations

What Europe should do:

- opening legal channels for migration and returning irregular migrants;

- establishing safe and quick procedures to guarantee asylum to refugees;

- reinforcing the Libyan economy and its local communities;

- building respect for the rule of law and human rights;

- broadening the scope of the EUBAM Libya.

Introduction

The refugee crisis is now over two years old, but the flow of migrants arriving in Europe still continues. Although refugees had been arriving in Europe from North Africa for many years, it was in 2015 that the issue made it onto the front pages. The refugee crisis, as we know it, led the EU to re-think its migration policy in a way that seemed unthinkable just a few years before. After a big shipwreck off the coast of Libya on 18 April 2015 claimed hundreds of migrants’ lives, the EU launched policies geared towards fighting people smugglers through Operation Sophia, ramped-up cooperation with transit countries and countries of origin, and eventually, offered comprehensive cooperation packages with countries of transit and origin.

Two years down the line, flows from Turkey and through the Balkans have dramatically reduced, but it’s a different story for flows from North Africa. Migration to Europe through Libya, in particular, is increasing and seems no more under control than it was two years ago. Current EU policies aimed at limiting migration are facing a stalemate situation. To yield any positive results, the goals and the policies themselves have to change. The elections taking place in key European capitals in 2017 could provide the shake-up needed for governments to adjust their policies. This paper seeks to propose what adjustments should be made, and how governments can implement them.

The EU is still struggling to find the right approach to managing migration flows from Libya. In particular, it faces difficulties in processing asylum applications and implementing readmission agreements. Asylum applications are still processed far too slowly and the system is overburdened because many see asylum as their only way to legally remain in Europe. The system could be at least partially relieved if channels for legal migration to Europe were opened.

Current policies focus on reducing the number of migrants, but end up achieving the opposite. Alongside proposing new policy positions for the EU, this paper will expose four incorrect assumptions that have contributed to policymaking on this issue in the past two decades. Secondly, before setting out what alternative policies should be implemented, this paper will evaluate current policies to understand which are useful and which need to change. The third part of this paper will provide some policy options to help member states manage migration into Europe. Finally, the conclusion reflects on the balance between member states’ and EU policies, and how coalitions of member states engaging in ‘enhanced cooperation’ (as laid out in the Lisbon Treaty) could be the solution to developing better policies.[1]

A blinkered and outdated approach

The EU has been under heavy pressure from individual member states to focus on two goals:

- Increasing control of the EU’s maritime borders, and

- reducing the number of refugees and migrants embarking on the treacherous sea crossing in the first place.

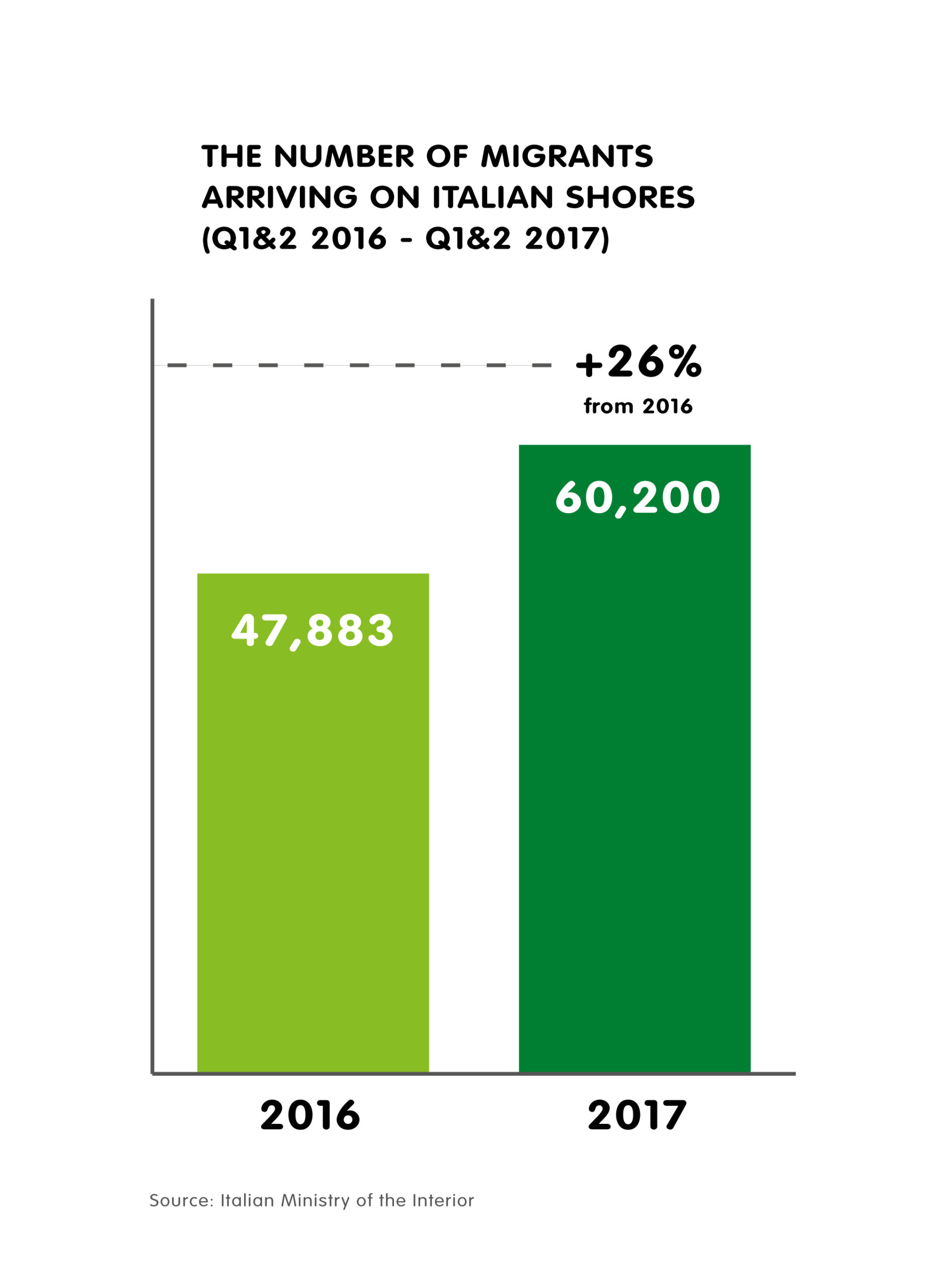

But these goals have not been achieved. Migration from Libya and Egypt to Italy increased by almost 18 percent in 2016, and was 25.7 percent higher in the first four months of 2017 than in the same period last year.[2]

These figures highlight the need for the EU and member states to re-think their approach to the migration challenge. A more comprehensive approach is needed that balances increased legal migration with faster and more effective returns of irregular migrants, while respecting their human rights. Policies aimed at ‘closing the borders’ simply do not work because they push more people towards illicit smuggling networks. Flows can only be cut by managing migration rather than simply attempting to cut it to zero.

The current approach is both outdated and blinkered. It’s high time that the EU and its member states abandoned entrenched policies from the late 1990s that make legal economic migration from outside Europe almost impossible. Shutting down processes for legal economic migration has caused more illegal migration, which in turn has increased the sense of physical and economic insecurity many EU citizens experience when they think about migration from the MENA region. Without a legal option for migration, many migrants and refugees resort to paying people smugglers to get them to Europe.

The trend of people-smuggling has only been exacerbated by the refugee crisis sparked by the Syrian civil war. Compared to refugees from other nations, Syrians were more willing (and able) to pay higher prices to cross the Mediterranean. This extra revenue allowed smugglers, whose business had been boosted by the restrictive policies of the 1990s, to significantly increase the number of people they could smuggle and lower their prices, creating a situation in which there were more seats, in worse boats, at a lower cost. Because of these market dynamics, even when Syrians began taking the more direct eastern Mediterranean route to flee the civil war in 2015, the number departing from Libya remained well above 100,000 per year.[3]

Europe’s primary method for stopping the flow of migrants out of Libya has been to boost Libya’s border/coastal patrol capacity rather than actively manage the flows. But the inconvenient truth is that even though policies for capacity building and stabilisation are important, their impact on migration flows will only be felt in the mid to long term. If the EU wants to curb irregular flows from Libya more quickly, it must sign readmission agreements with countries of origin, and to do that, it must propose channels for legal migration.

Ultimately, the best way to respond to the anxiety of their citizens about migration is for European leaders to focus on the integration of migrants in the European society. With no opportunity for legal migration, it is often ‘illegal’ migrants who end up in Europe, which makes integration all the more difficult. because these irregular migrants tend to find jobs in the informal sector and generally live on the margins of society. While it is not the point of this paper to discuss integration of migrants, it is worth remembering that a managed flow of people makes integration easier.

Re-thinking European assumptions

Four basic assumptions have shaped Europe’s collective response since 2015, and underpinned European policies since the mid-1990s. These assumptions need to be abandoned if a more effective policy is to emerge. These are:

Assumption 1: Refugees can find a different destination to migrate to

The consensus in Europe, shared both by mainstream and insurgent parties, is that although Europe has some obligations, the vast majority of refugees should broadly settle in safe third countries instead of coming to the EU.[4] This principle was a cornerstone of the EU-Turkey refugee deal, and is paired with the belief that economic migrants should not be allowed on the continent at all.[5] Yet, it is hard to find any credible safe third country that refugees from North Africa could go to.

Assumption 2: We can close our borders to economic migrants

Starting with restrictions on economic visas in the mid-1990s, policymakers responded to public anxieties over the growing foreign population in Europe with an effort to shut the continent off to economic migrants − an approach that exacerbated a deadly trend: people smuggling. People smugglers working the route from Libya to Italy flourished in the early 2000s after Italy approved the Bossi-Fini bill in 2002, which tightened regulations for migrants attempting to obtain a residency permit.[6] In fact, irregular migrants still found jobs in Italy and elsewhere in Europe on the black market. Consequently, the number of undocumented migrants in Italy doubled between 2002 and 2006.

Assumption 3: Sending rescue boats creates an incentive to migrate

After the first big shipwrecks in the Mediterranean hit the news in 2013, Europeans started debating the pros and cons of enhanced ‘Search and Rescue’ (SAR) missions. Some member states argued that saving more migrants in the Mediterranean would create an incentive for them to take the treacherous journey. For this reason, in October 2014, under heavy pressure from the UK government and then Home Secretary Theresa May, the EU suspended search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean, only to resume them six months later.[7] The UK’s Deputy Prime Minister at the time, Nick Clegg, admitted that halting rescue operations does not stop migration flows.[8]

Today, the EU focuses more on controlling borders and fighting people smugglers than on rescue operations, even as deaths in the Mediterranean continue to rise, indicating that the danger faced on the route does not act as a deterrent.[9] Since late 2013, the number of migrants coming to Europe through Libya has skyrocketed. Up until 2013, arrivals averaged roughly 30,000-40,000 people per year. But the figure has been more than five times that for each of the last three years. This increase has taken place despite an unprecedented level of EU coordination on migration policy over the last two years.

Assumption 4: Money and build-up of local forces can solve the problem

European policies, both at EU and at member state level, are geared towards working with the most popular countries of origin and transit for migrants by providing financial assistance and training for security forces. There is an assumption in Europe that a combination of the two will halt illegal migration, but the EU’s dealings with Libya show that simply sending money and building capacity is not enough.

What Europe already does

Since the deadly shipwreck of 18 April 2015, the EU has put in place several measures to fight people smugglers and improve control of borders in cooperation with countries of origin. These measures are outlined below:

The Malta Declaration

On 2 February 2017, Italy signed a memorandum of understanding[10] with Libya to resume implementation of the 2009 Friendship Treaty between the two countries (which includes generous economic provisions for Libya) in exchange for a significant reduction in migration flows.[11] The EU followed up a day later with the Malta Declaration, endorsing the terms of the Italy-Libya agreement. The goal, as per the Malta Declaration, is to “significantly reduce migratory flows by enabling the Libyan Coast Guard to ‘rescue’ a higher number of migrants and bring them back to Libya before they reach EU ships or EU territory”. It is effectively a lightly concealed outsourcing of

‘push-back’ activities.[12] Ultimately, the goal of this policy is, as EU Council President Donald Tusk said, to close the central Mediterranean route in the same way that the Balkan route from Turkey and Greece was closed last year.[13] On 12 April, the EU Trust Fund for Africa earmarked €90 million for implementation of the Malta Declaration through programmes to assist migrants in Libya, build Libyan institutional capacities and support city-based programmes for economic development.[14] But a significant component of Europe’s strategy is to build-up the capacity of the Libyan Coast Guard, which has already started to bring migrants back to Libya before they reach rescue ships sent by the EU or European NGOs.[15]

Operation Sophia

One of the key measures has been the joint anti-smuggling naval mission, Operation Sophia, otherwise known as EUNAVFOR MED, which was created following the big shipwreck in 2015.[16] Vessels involved in the mission block smuggling routes and conduct rescue operations. On 20 June 2016, the mission’s mandate was upgraded to include training of the Libyan Coast Guard and enforcement of the UN arms embargo on Libya.[17] Aside from arresting many smugglers, Operation Sophia has improved control over Europe’s southern border and, through enforcement of the UN arms embargo, can help to make sure no weapons illegally reach Libya from the sea.

Training the Libyan Coast Guard

In October 2016, the EU, through Operation Sophia started training the Libyan coast guard and navy. The first batch of trainees has now graduated and a second batch is being trained at the time of writing. The Mediterranean is effectively the EU’s southern border and it cannot be controlled without cooperation and a build-up of forces on the Libyan side. Although the EU’s flagship policy of training the Libyan coastguard has been perceived as part of a policy of concealed push-backs, it is necessary. And although these push-backs help the EU to protect its own borders, it is important to note that they do not constitute an ‘outsourcing’ of the solution. Training activities give Libya’s coastguard solid skills. Among those skills, increased awareness of human rights and knowledge of how to save lives at sea. A coherent EU policy on migration must involve cooperation between forces on both sides of the border.

The EU Border Assistance Mission to Libya (EUBAM)

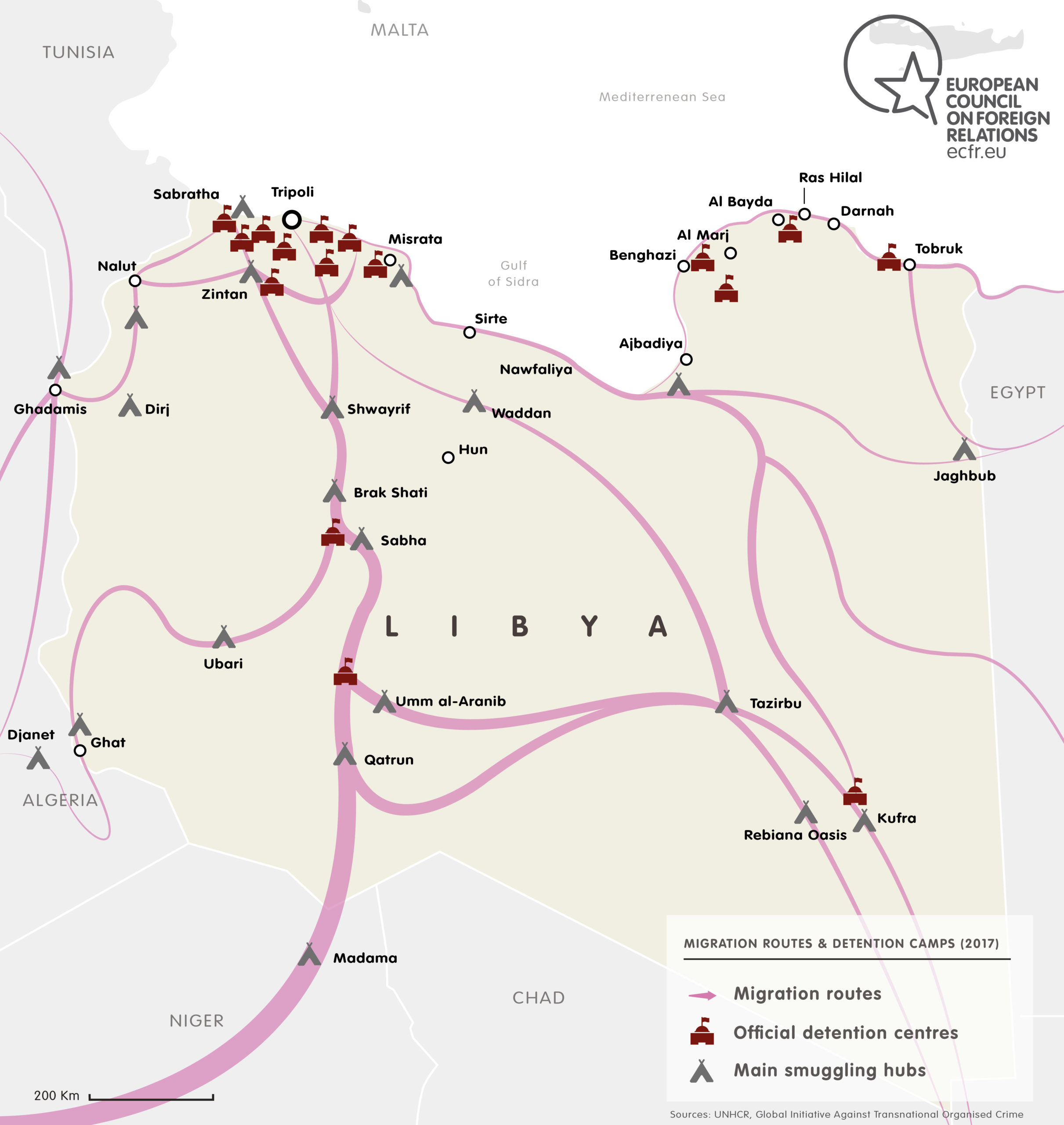

EUBAM Libya was revamped in 2016 and tasked with building up Libya’s capacity to control its borders, strengthening the rule of law, and improving investigative capacities to bust smuggling rings. However, its mandate is still limited because it engages mostly with state actors such as ministries or government agencies that are traditionally weak in Libya, and which have little latitude to work and negotiate with powerful sub-state and non-state actors.

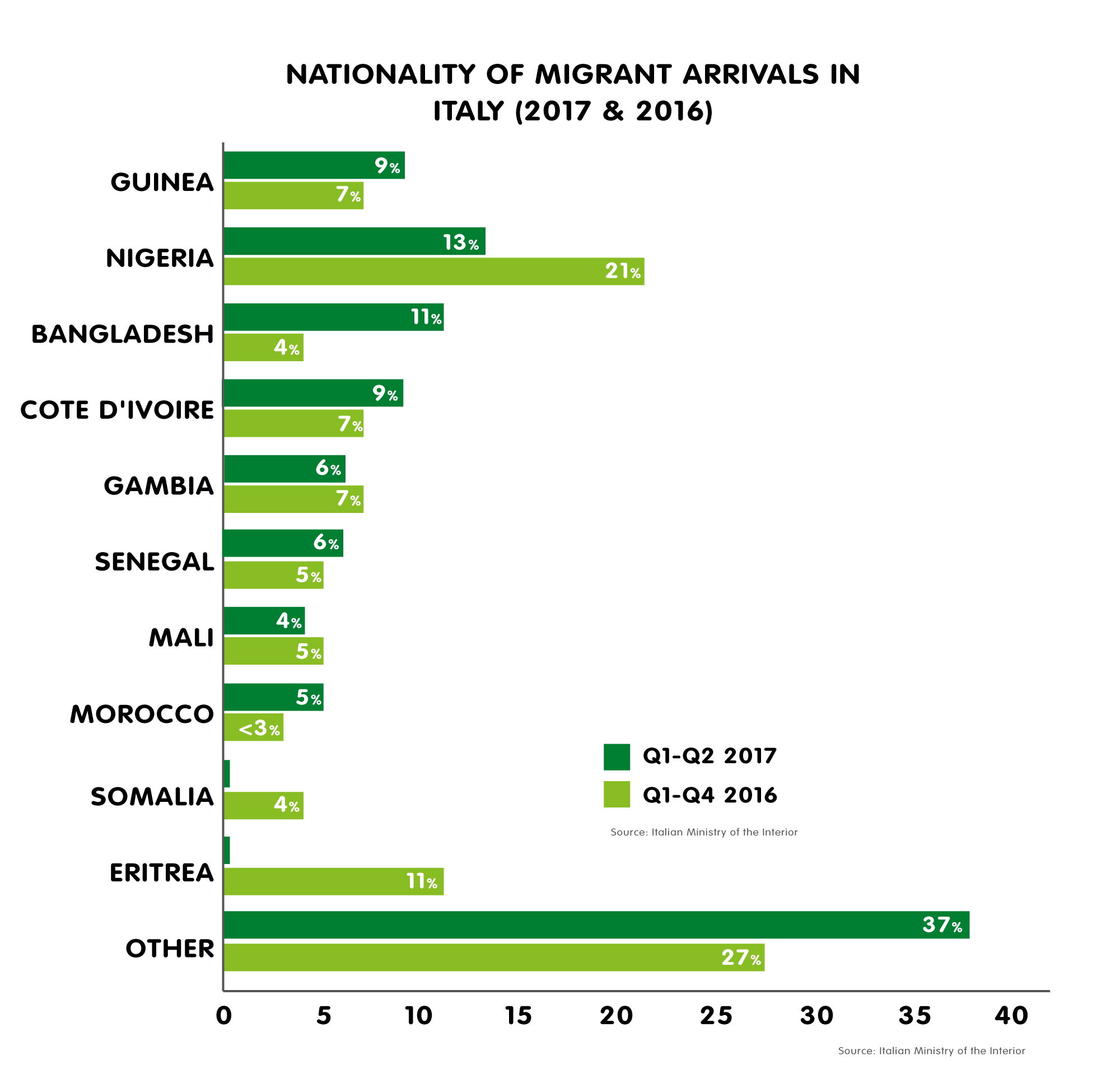

The Partnership Frameworks with countries of origin and transit

In June 2016, the European Commission launched partnerships with countries of origin and transit.[18] These Partnership Frameworks are bespoke packages with countries such as Niger, Mali, Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Senegal.[19] The EU is meant to deliver development aid, strike trade agreements, conduct capacity-building for the security sector, and, where possible, increase mobility for migrants. However, the EU itself has little leverage over legal migration because most categories of visas are still issued by member states. The EU also has few powers when it comes to striking trade agreements, since even the simplest of agreements can take years to negotiate. This leaves the EU with just capacity-building and assistance as areas in which it can hope to make a real difference.

Fighting the root causes of migration

In the last two years, several financial instruments were adopted by the EU to fight the root causes of migration. Following the EU-Africa summit in Valletta in November 2015, the EU Trust Fund for Africa was created to finance measures to manage migration flows across the continent. The European External Investment Plan is also tasked with fighting the root causes of migration.

But fighting the root causes of migration by giving development aid money can be counterproductive if one’s goal is to reduce migration flows. There is plenty of literature demonstrating that as a country moves up the development ladder its migration rate tends to increase because more people achieve the level of education and health that enables them to migrate.[20] This does not mean Europe should stop its development aid, quite the opposite. It means that it should measure the impact of its aid by the improvement of the economic performance of target countries, not in the reduction of migration flows.

What Europe should do

Despite its best efforts, the EU has far fewer instruments at its disposal compared to member states, and unfortunately, few of these instruments are likely to reduce migration or make it more manageable. But Europe is not without alternative options that could create a win-win situation, including opening legal channels for migration and returning irregular migrants; establishing safe and quick procedures to guarantee asylum to refugees; reinforcing the Libyan economy and its local communities; building respect for the rule of law and human rights; and finally, broadening the scope of the EUBAM Libya.

Opening legal migration channels to close illegal ones

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), about 61 percent of those who arrive in Italy from Libya do not qualify for any form of protection. The return of these undocumented migrants to their home countries is one of the EU’s top priorities, but it is unlikely to be fulfilled in the absence of readmission agreements (i.e. forced returns) with several countries of origin. Some migrants are exploiting loopholes in the current Italian legislation, which automatically labels some nationals economic migrants rather than refugees eligible for asylum. For example,, Moroccans or Bangladeshis are generally labelled economic migrants and ordered to leave Italy within seven days of arrival. In the absence of a readmission agreement, many such migrants use these seven days to ‘go underground’ and find a job in the informal sector.

Even though readmission agreements are key to managing irregular migration, putting them into effect has so far proved a daunting task. Unlike with the Turkey-Balkans route, migrants taking the central Mediterranean route originate from multiple countries and the mix of countries is constantly changing. The EU and its member states have not, so far, been able to make any significant progress on the issue of forced returns, in part due to the failures of the current European approach.

At present, the EU offers financial assistance and development aid to secure readmission agreements with countries of origin, but this assistance is usually insufficient to offset the profits that local smugglers make from irregular migration. For these countries, deals based on ‘EU money in exchange for smaller flows’ present an attractive opportunity: reduce flows enough to justify European payments while increasing the bribes requested from migrants and smugglers who continue to make their way to Europe. Even for smugglers, a small reduction in migration flows helps business: when there are fewer available ‘tickets’ the trip to Europe becomes more expensive.

If the EU or some of its member states want to implement quick and effective readmission agreements additional incentives are required that target both the governments and the people of the countries of origin.

One such incentive could be visas for migrants in exchange for a commitment to swiftly take back all citizens of the same country who have arrived illegally on EU territory. Issuing visas would not only enable Europe to manage migrant flows, but boost remittances to countries of origin too − a win for both sides. The worldwide flow of remittances is estimated by the World Bank to be worth over $400 billion dollars annually and it far outweighs any development aid money the EU can offer.[21] This kind of ‘aid’ costs nothing to the taxpayer.

Legal migration arrangements would also undercut human smuggling, because only migrants who have never attempted illegal migration would be granted visas. To facilitate absorption and integration, visas for economic migrants could be set at one quarter of illegal arrivals in 2016 from each country, or any other fraction of past flows that is both realistic in terms of absorption in EU countries and attractive for countries of origin. Visas could be assigned by lottery to all citizens of the country of origin who have never attempted illegal migration and who register for the programme.

The EU does not need to reinvent the wheel on this issue. It already has mobility partnerships with some countries, through which visa issuance is linked to more effective border controls by countries of origin and transit, although the overall focus of these partnerships was prevention of illegal immigration rather than labour mobility.[22] So far, only Tunisia and Morocco among North African countries have mobility partnerships with the EU. No mobility partnership has been signed with any sub-Saharan countries.

The European Commission has, on numerous occasions, considered a ‘grand bargain’ that accepts some legal migration for stricter implementation of readmission agreements. These deals have been dropped in many cases because of political constraints (even mentioning legal economic migration sounds toxic to the European electorate). But even if there was public buy-in, the EU has its hands tied because it holds very few powers for issuing work visas, most of which rest in the hands of member states.

The EU may not have the overall power to issue work visas, but it could incentivise member states to get on board with its plans, particularly if there is a clear link between granting work visas for legal migration and being protected from illegal migration by readmission agreements. This system could be implemented either through enhanced cooperation, as per the Lisbon Treaty, or through multilateral agreements between interested EU member states and each country of origin or transit.

Fair and quick procedures for asylum-seekers

Readmission agreements come into force when an asylum-seeker’s application is rejected or when an economic migrant is trying to illegally enter an EU member state. However, the system for processing asylum-seekers, and assessing the validity of their applications, needs to be improved to make it fairer and more efficient.

Today, asylum-seekers disembarking in Sicily can wait months, if not years, for their cases to be adjudicated. Italy recently changed its legislation to speed up asylum processing, but at the expense of eliminating in-person interviews. Instead, asylum-seekers must submit a short recorded clip explaining their situation, without any interaction with the panel. Although this change in procedure may reduce processing time − eliminating the wait time for asylum interviews − it undercuts the evaluation process by preventing applicants from effectively presenting their case.

Ultimately, the dilemma that comes with choosing between thorough processing (which takes time), and high-level but quick processing, is a false one. It is possible to be both thorough and efficient. The European Stability Initiative, a think-tank focused on southeast Europe and migration issues, published a comprehensive proposal which recommends that an EU Asylum Mission be deployed to EU ports of disembarkation, such as Sicily. This mission would “deal with claims within four weeks, while ensuring the quality of decisions through quality control mechanisms and trained staff, backed up by competent interpreters and with available legal aid”.[23] This proposal offers a viable option for improving the asylum application process.

In addition, setting up an effective screening mechanism for asylum-seekers would help eliminate the need for them to risk the dangerous Mediterranean boat crossing in the first place by allowing for mechanisms in which asylum-seekers reach Europe safely and their applications can be quickly and fairly assessed. The EU should promote humanitarian corridors[24] and sponsorships (see the Canadian model)[25] for refugees, enabling EU individuals, organisations, or local communities to take responsibility for accepting and managing the resettlement of refugees. These refugees would be identified near their country of origin and be flown directly to Europe with a temporary visa, further undercutting the business model of smugglers. They would then undergo the fast and fair processing described above and their visa would have territorial limits, so they would not be allowed to leave the country of destination until their application has been fully processed.

In Libya: promote migrants’ rights, help reform the economy, support municipalities

Libya currently lacks a strong central government and will likely continue to for some time. EU policies should be realistic about the short-term progress Libya can make on migration management and avoid giving the impression − now widespread among Libyan policymakers − that the EU wants to transform Libya into a dumping ground for migrants. Knowledge of the complex workings of the smuggling sector is crucial and reports such as that of the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime offer critical insights into this underground industry.[26] EU and bilateral policies can have an effect by normalising respect for the human rights of migrants, while strengthening local economic and social resilience, and approving reforms of government spending to decrease incentives for smuggling.

First, the EU and its member states should promote respect for the rights of migrants held in detention centres and work to raise living conditions of migrants in Libya. As emphasised in numerous interviews with migrants who arrive in Europe from Libya, violations of human rights are one of the main drivers of migration. The EU and its member states could do four things to improve the situation:

- Support the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and UNHCR’s access to detention centres by providing funding and expert officers;

- Increase support for IOM’s programmes for voluntary returns, particularly for vulnerable migrants;

- Work with the Libyan central government, municipalities, and EUBAM Libya, to improve registration of migrants and provision of basic rights; and

- Support Libyan civil society organisations that conduct monitoring and inspections of detention centres.

Second, the EU should avoid pitting Libyans against migrants. International assistance should flow to local Libyan communities where migrants are hosted or where they transit, as well to national institutions. At present, less than half of the funds earmarked by the EU Trust Fund for the implementation of the EU-Libya deal will go to Libyan municipalities – and the total funding is a mere €90 million.

It remains to be seen whether Libya’s weak and disorganised national institutions can absorb and effectively administer even this initial €90 million. Further funding should be contingent on the effective use of current funds, or should be directed to Libyan municipalities or the UNDP Stabilisation Facility, which has already implemented many projects in Libya.[27] Among other things, EU assistance could support local projects to: expand the installation of solar panels to guarantee energy supply, particularly to desert communities that often go weeks without electricity; provide micro-credit, particularly targeting women entrepreneurs; improve local healthcare and facilitate migrants’ access to healthcare along the transit route, contributing to an early warning system regarding migration flows; and improve other local public services, thereby contributing to the stabilisation and good governance of communities in the fields of education, sewage, and waste collection.

Third, but no less important, the EU with its expertise in economic reform and budget oversight, is best placed to assist the Libyan government to reform its economic policy. Such reforms should be launched to undercut the smuggling economy. The main area that needs to be reformed is subsidies, which smugglers routinely exploit to fund their business. Despite Libya’s institutional collapse, the Libyan government still heavily subsidises some goods: one litre of petrol in Libya costs LYD 15 cents (€ 0.10 at the official exchange rate) and smugglers sell it in neighbouring countries often for ten times as much. The money is then reinvested in the smuggling of drugs, weapons, or people.

The EU could help Libyan institutions impose incremental reforms to reduce the amount of goods that can be smuggled (there is enough subsidised petrol to satisfy domestic consumption three times over), while aiming to legalise some of the informal economic activity currently managed by smugglers, following in the footsteps of neighbouring Tunisia and Algeria, which are trying to ‘formalise the informal’. Legalising less harmful aspects of smuggling could enable a more effective crackdown on the smuggling of people, drugs, and weapons. It would also help generate legal routes to employment for those currently involved in people smuggling.

Finally, the EU should support current Libyan efforts to curtail smuggling by providing intelligence, monitoring of flows, capacity building, and equipment to Libyan forces, assuming they prove to be reliable over time.

An EU Mission to build up Libyan capacity

EUBAM Libya was created after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi to help build Libya’s capacity to control its own borders. But it was withdrawn from Libya in 2014 when the civil war broke out and it is only being re-implemented very slowly under the new leadership. Its mission is still limited, for instance, in the type of actors with which it can engage. At the moment it works with state actors, whose influence and reach in the country is limited due to the level of fragmentation and the number of informal non-state actors. The EU should review the mandate of EUBAM, treating it as a proper Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) mission. The mission should be allowed to engage with and build the capacities of sub-state and non-state actors, such as municipalities, tribes, and civil society. Member states could contribute to these efforts by deploying political officers and mediators.

EUBAM should work towards enforcing localised models of border control and increased state effectiveness in smuggling hubs. On the coast, EUBAM should train Libyans on registration of rescued migrants. While at the level of the central government, EUBAM should work on building ‘networks of legality’ − rebuilding the judicial and police infrastructure, from the Criminal Investigation Departments to the offices of the public prosecutors. Ultimately, all these measures would support Libyans in building an accountable, efficient, and impartial law enforcement system, which is one of the main needs felt by the population in a country that is effectively under militia rule.

Conclusions: Breaking taboos, managing public expectations

Managing public expectations is a key part of implementing any new policy on migration – especially ones that break taboos. Politicians in Brussels and in national capitals need to be clear that there is no quick fix for reducing migration flows unless Europeans are ready to begin allowing some legal economic migration. In the absence of that, Europe can only work on medium-term strategies to gradually reduce flows and make them more manageable, with impacts likely to be felt in four to six years.[28]

In the last two years EU policy-makers have struggled to implement a comprehensive policy on migration in the face of member states that still hold outdated and ineffective assumptions. Although transferring power from member states to the EU on migration might encounter resistance, creating a coalition of member states working through EU institutions and implementing a more pragmatic migration policy could offer a way forward.

Ultimately, leaders within the EU and member states need to present options for addressing migration that overcome the popular perception that ‘closing the borders’ will resolve the problem. On the contrary, policies focused on halting migrant flows merely push more people towards illegal means of entry into Europe, creating a larger market for people smugglers. Irregular migration, in turn, feeds popular European perceptions of physical insecurity connected to crime, and of economic insecurity due to competition for jobs and public services. These feelings, in turn, contribute to the fortunes of anti-immigration parties, which have ridden the wave of anxiety arising from the perceived link between immigration and crime or terrorism.

The alternative to a ‘closed borders’ approach is not merely to open borders, but to build borders that can be managed, and through which non-European immigrants are properly identified and registered. Elections and opinion polls throughout Europe demonstrate that anti-immigration parties garner a consistent minority but that in many western European member states there is a possible majority who consent to a more realistic policy on migration from Africa.

Chancellor Merkel’s oft-quoted statement at the peak of the refugee crisis in 2015: “Wir Schaffen Das” (we will cope with it) suggests that countries are doing their best to deal with the emergency and make the best of it. But the German verb schaffen actually means ‘managing’ and this is really what Europe needs to do: deal with migration as an inevitable consequence of globalisation, a fact of life that has been there since man has been on earth, and an issue that needs to be handled in a constructive and realistic way.

About the author

Mattia Toaldo is a senior policy fellow for the Middle East and North Africa Programme at ECFR where he focuses on Libya and migration. His most recent publications for ECFR are “After ISIS: How to Win the Peace in Iraq and Syria” (2017 co-authored), “Intervening Better: Europe’s Second Chance in Libya” (2016), and “Libya’s Migrant-smuggling Highway: Lessons for Europe” (2015).

Acknowledgements

The author owes special thanks to Roderick Parkes from EU ISS for his extensive written and oral comments on earlier versions of this paper. Comments from Andrew Geddes at the European University Institute and Hedi Giusto at FEPS were also particularly helpful. Alan Bugeja and the Maltese mission to the EU deserve special thanks for organising two very interesting and stimulating workshops on this issue which greatly helped the author to develop his understanding and his ideas. Many EU and member state officials who shall remain anonymous have contributed to both the author’s understanding of the issue and development of policy options. Finally, ECFR co-chair Emma Bonino deserves the author’s gratitude for her inspiration and her challenging but always stimulating remarks on how Europe should deal with the migration file.

While providing comments and inspiration for this paper, none of the individuals mentioned above have any responsibility in the ideas and analysis provided in this work which are the author’s only.

With the kind support of

[1] Article 20 of the EU Treaty allows for “enhanced cooperation” which is an agreement between 9 member states to work on closer integration on a specific policy issue. Enhanced cooperation must be approved by parliament and there needs to be “adequate time” for all member states to agree to this policy within the EU Council before resorting to this “coalition of the willing”. Enhanced cooperation in the field of migration and asylum had been suggested two years ago, see Valentin Kreilinger, “Proposal to use Enhanced Cooperation in the Refugee Crisis”, 21 September 2015, Delors Institut, available at http://www.delorsinstitut.de/en/publications/topics/eu-institutions-and-governance/proposal-to-use-enhanced-cooperation-in-the-refugee-crisis/.

[2] “Cruscotto Statistico Giornaliero 30 Maggio 2017”, Liberta Civili Immigrazione, available at http://www.libertaciviliimmigrazione.dlci.interno.gov.it/sites/default/files/allegati/cruscotto_statistico_giornaliero_del_31_maggio_2017.pdf.

[3] On how the broader refugee crisis impacted migration through the central Mediterranean, see: Mattia Toaldo, “Libya’s migrant-smuggling highway: Lessons for Europe”, the European Council on Foreign Relations, 10 November 2015, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/libyas_migrant_smuggling_highway_lessons_for_europe5002.

[4] Erik Christopherson, “What is a safe third country?”, Norwegian Refugee Council, 9 March 2016, available at https://www.nrc.no/news/2016/march/what-is-a-safe-third-country/.

[5] Mattia Toaldo, “The EU Turkey deal: Fair and Feasible?”, the European Council on Foreign Relations, 16 March 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_eu_turkey_deal_fair_and_feasible6030.

[6] “Harsh Immigration Law Passed in Italy”, the European Roma Right Centre, 7 November 2002, available at http://www.errc.org/article/harsh-immigration-law-passed-in-italy/1598.

[7] Alan Travis, “UK axes support for Mediterranean migrant rescue operation”, the Guardian, 27 Octobe r 2014, available at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/oct/27/uk-mediterranean-migrant-rescue-plan.

[8] Rowena Mason, “Cameron and Clegg admit axing search and rescue in Mediterranean has failed”, the Guardian, 22 April 2015, available at https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/apr/22/cameron-and-clegg-admit-axeing-search-and-rescue-in-mediterranean-has-failed.

[9] Ben Quinn, “Migrant death toll passes 5,000 after two boats capsize off Italy”, the Guardian, 23 December 2016, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/record-migrant-death-toll-two-boats-capsize-italy-un-refugee.

[10] “Migranti: accordo Italia-Libia, il teso del memorandum”, Repubblica, 2 February 2017, available at http://www.repubblica.it/esteri/2017/02/02/news/migranti_accordo_italia-libia_ecco_cosa_contiene_in_memorandum-157464439/.

[11] “Malta Declaration by the members of the European Council on the external aspects of migration: addressing the Central Mediterranean route”, the European Council, 3 February 2017, available at http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/01/03-malta-declaration/.

[12] Mattia Toaldo, “The EU deal with Libya on migration: A question of fairness and effectiveness”, the European Council on Foreign Relations, 14 February 2017, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_eu_deal_with_libya_on_migration_a_question_of_fairness_a.

[13] “Central Mediterranean migrant route to be closed, Tusk says”, ANSAMED, 3 April 2016, available at http://www.ansamed.info/ansamed/en/news/nations/slovenia/2017/04/03/central-mediterranean-migrant-route-to-be-closed-tusk-says_7356c675-3310-4ca8-bd71-5c365c2ac60c.html.

[14] “EU Trust Fund for Africa adopts €90 million programme on protection of migrants and improved migration management in Libya”, the European Commission, 12 April 2017, available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-951_en.htm.

[15] “Libyan coastguard turns back nearly 500 migrants after altercation with NGO ship”, Reuters, 11 May 2017, available at http://in.mobile.reuters.com/article/idINKBN1862OK.

[16] For a more in-depth view of EU policies on migration from Africa, see Luca Barana and Mattia Toaldo, “The EU's migration policy in Africa: Five ways forward”, the European Council on Foreign Relations, 8 December 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_eus_migration_policy_in_africa_five_ways_forward.

[17] “EUNAVFOR MED Operation Sophia: mandate extended by one year, two new tasks added”, the European Council, 20 June 2016, available at http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/06/20-fac-eunavfor-med-sophia/?utm_source=dsms-auto&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=EUNAVFOR%20MED%20Operation%20Sophia%3A%20mandate%20extended%20by%20one%20year%2C%20two%20new%20tasks%20added.

[18] “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council and the European Investment Bank on establishing a new Partnership Framework with third countries under the European Agenda on Migration”, the European Commission, 7 June 2016, available at https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/20160607/communication_external_aspects_eam_towards_new_migration_ompact_en.pdf.

[19] “Migration partnership framework: A new approach to better manage migration”, the European External Action Service, June 2016, available at https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/factsheet_ec_format_migration_partnership_framework_update_2.pdf.

[20] Michael Clemens, “Development Aid to Deter Migration Will Do Nothing of the Kind”, News Deeply, 31 October 2016, available at https://www.newsdeeply.com/refugees/community/2016/10/31/development-aid-to-deter-migration-will-do-nothing-of-the-kind.

[21] Dilp Rathe, “Remittances to developing countries decline for an unprecedented 2nd year in a row”, The World Bank, 21 April 2017, available at http://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/.

[22] “Mobility partnerships, visa facilitation and readmission agreements”, the European Commission, available at https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/international-affairs/eastern-partnership/mobility-partnerships-visa-facilitation-and-readmission-agreements_en; and Julia Lisiecka and Roderick Parkes, “Returns diplomacy: levers and tools”, EU ISS, April 2017, available at http://www.iss.europa.eu/uploads/media/Brief_11_Returns_diplomacy.pdf.

[23] “The most dangerous Wizard in the EU”, European Stability Initiative, 7 October 2016, available at http://www.esiweb.org/index.php?lang=en&id=67&newsletter_ID=112%20-%205.

[24] “Humanitarian corridors for refugees”, Sante Gidio, available at http://www.santegidio.org/pageID/11676/langID/en/Humanitarian-Corridors-for-refugees.html.

[25] “Guide to the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program”, Government of Canada, available at http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/publications/ref-sponsor/.

[26] “The Human Conveyor Belt: Trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya”, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2017, available at http://globalinitiative.net/report-the-human-conveyor-belt-trends-in-human-trafficking-and-smuggling-in-post-revolution-libya/.

[27] “Stablization Facility for Libya: What the Project is About”, UNDP, available at http://www.ly.undp.org/content/libya/en/home/operations/projects/sustainable-development/stabilization-facility-for-libya/.

[28] Author’s interviews with European and Libyan officials.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.