Big is beautiful? State-owned enterprise mergers under Xi Jinping

Chinese state-owned enterprise mergers raise fears of ‘too big to regulate’ companies

Introduction

by François Godement

It is merger season again in China, as evidenced by the sources drawn on in this special issue of China Analysis. But who really knows why? Our contributor Wendy Leutert points out how the government’s goals have shifted within the last year alone. In September 2015, new guidelines emphasising the importance of separating state suppliers of public goods from more commercial state firms suggested a possible shift towards the latter having to play by the rules of the market. Today, the more traditional goal of mopping up excess supply and inefficient companies seems to have taken over.

However, the list of mergers for the past two years highlights another reality: the mergers seem to be building up new strategic monopolies in addition to the natural monopolies that already exist. And because of the wave of ‘going out’ – official encouragement to invest overseas – investments of recent years, this is likely to also result in achieving global number one status in some cases. A monopoly of Chinese railways, an oil monopoly, a chemical monopoly would constitute in each sector the world’s largest company.

Not necessarily the most efficient, though. There seems to be hardly any echo of the famous restructuring of the state-owned enterprises by former prime minister Zhu Rongji in 1998: then, the massive shedding of state property and jobs and restructuring of key companies stemmed the tide of red ink in China’s state sector. A decade of surging profits still lay in the future. As one of the sources for this issue courageously states, one would no longer see today a level playing field between the current premier and one of these giants.

Another target seems more likely to be in reach: cutting down the unnecessary and sometimes cut-throat competition between Chinese state-owned enterprises abroad. Again, limiting competition is a natural byproduct of monopoly power. But is this going to go down easily with China’s major partners? One thinks of the current bid by ChemChina to take over Syngenta, the Swiss agrochemical giant, with a reported offer of $43 billion. The European Commission already has an ongoing enquiry into the possible monopoly position this acquisition could create. The recent reports in October 2016 that ChemChina will merge with Sinochem, resulting in the world’s biggest chemical firm, adds to the difficulty of the deal over Syngenta.

It seems likely that the current wave of mergers for large SOEs has little to do with international strategy, where plurality is often an asset. Rather, it seems that the top-down approach of reform in the state sector is simply creating a new set of huge hierarchical structures – as much bureaucracies as companies. Unquestionably, the job will be harder for regulators and overseers of these giants. But it is equally possible that the central Party-state has simply decided it cannot track and control a plurality of companies. One is reminded of the old Soviet and Chinese management motto of the 1950s – ‘yi zhang zhi’ (一长制) . Or, in more folksy terms, ‘I want to see only one head’.

Nor is the Party-state apparently resigned to take the opposite option of going to market, and that also differentiates the current ongoing process from the Zhu Rongji reforms of the late 1990s.

To be sure, the above decisions appear to zigzag between contradictory objectives rather than strike a straight path towards a single goal. Stay tuned, therefore, for possible new developments at the top of China’s command economy.

State-owned enterprise mergers: will less be more?

by Wendy Leutert

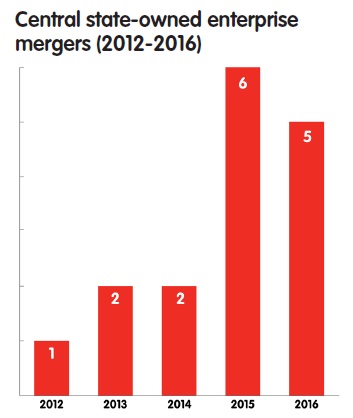

Mergers were not initially a key element of the Xi Jinping administration’s strategy for reforming central state-owned enterprises (SOEs).[1] But in 2015, Beijing launched a dramatic wave of mergers among central SOEs. The Chinese leadership’s goals for these mergers range from promoting competitiveness and the One Belt, One Road initiative abroad, to reducing surplus industrial capacity and advancing “supply-side reform” at home. Some Chinese analysts believe that SOE mergers could be a crucial tool in achieving these strategic aims. However, others worry that by decreasing competition and creating larger and more complex companies, mergers will facilitate potential rent-seeking behaviour and negatively impact efficiency, competition, and the quality of goods and services.

Beijing embraces mergers

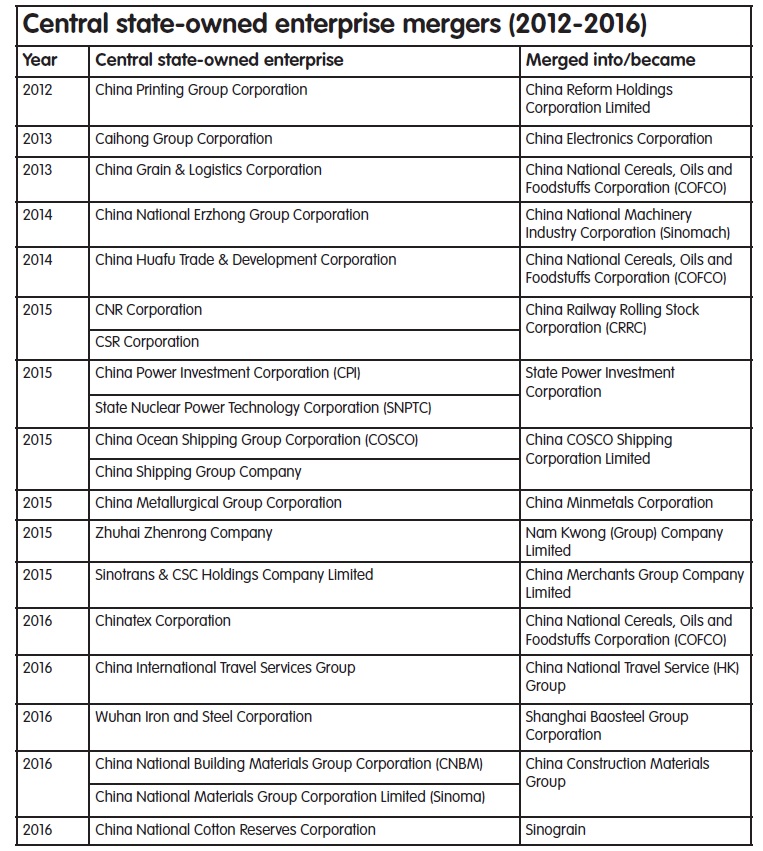

Between 2012 and 2014, only five mergers of central SOEs took place. However, between 2015 and November 2016, this number has more than doubled: eleven central SOE mergers have occurred, in industries such as shipping, commerce, construction, steel, services, and energy (see the table for a complete list). Some of these mergers have involved one central SOE being absorbed into another, while others have entailed the combination of two central SOEs to form a new conglomerate. The graph shows the rise in the number of mergers among central SOEs since 2012.

At first, Chinese analysts considered the new wave of mergers a strategy of combining strong performers to boost central SOEs’ international competitiveness and push forward the Xi administration’s One Belt, One Road initiative. They saw evidence for this in the 2015 merger of China Power Investment Corporation (CPI) and State Nuclear Power Technology Corporation (SNPTC) to form State Power Investment Corporation, in which CPI’s vast capital resources complemented SNPTC’s advanced technology. They also cited the merger of CSR Corporation and CNR Corporation to create the China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation, one of the world’s largest companies in the railway sector – which is a priority industry for the One Belt, One Road initiative.[2] Pointing to these two mergers, Li Jin said in April 2015: “This round of central state-owned enterprise mergers is not aimed at firms in industries with surplus capacity, but rather at giant central state-owned enterprises in strategically important industries, creating alliances of the strong (强强联合, qiangqiang lianhe).”[3] He said that the logic of this move was to boost Chinese state firms’ global competitiveness by eliminating aggressive “price wars” (价格战, jiage zhan) among them, thereby restoring competition on the basis of technological advantage and other core competencies.

Reform roadmap points to mergers ahead

The Xi Jinping administration clarified the role of mergers in its SOE reform strategy in September 2015 with the “Guiding Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Deepening State-Owned Enterprise Reform”, a framework text that was to be followed by a series of detailed policy documents.[4] Numerous actors participated in drafting the Guiding Opinions, including the Central Leading Group for Deepening Overall Reform, the Leading Group for State-Owned Enterprises Reform under the State Council, and the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), and the final text reflects the political compromises and intense negotiations that preceded its publication. Rather than foregrounding mergers as the primary instrument for overhauling the state-owned economy, the Guiding Opinions refer to mergers as one method among others in a broader reform strategy. The text emphasises the need to regroup SOEs according to their function: a public class (公益类, gongyi lei) and a commercial class (商业类, shangye lei). This separation would in theory form the basis for a future “dual-track” reform approach, with different strategic objectives and performance assessment metrics for firms in each category. The Guiding Opinions state that the development of state-owned capital investment and operating companies will provide further impetus for the “cleaning up and exit of some state-owned enterprises, the restructuring and consolidation of some [i.e., mergers], and the innovation and development of others” (清理退出一批、重组整合一批、创新发展一批国有企业, qingli tuichu yi pi, chongzu zhenghe yi pi, chuangxin fazhan yi pi guoyou qiye).

Mergers gain momentum under supply-side reform

At the Central Committee’s economic meeting on 10 November 2015, Xi Jinping’s proposal of a new policy of “supply-side reform” renewed the momentum for central SOE mergers. This new policy also shifted the objective of the mergers from boosting “national champions” to tackling “zombie firms.”[5] Key priorities of supply-side reform include reducing industrial over-capacity, improving company performance, and optimising product structure. Advocates believe that mergers can advance the aims of supply-side reform in several ways: they can enable merged companies to coordinate capacity cuts, particularly in the production of low-quality products; they can help to reduce losses by melding struggling firms into stronger performers; and they can stabilise prices for products that were previously undervalued because of competition between SOEs. As Li Jin observes: “At present, the biggest problem of over-capacity in the steel sector is that industrial capacity is too dispersed, causing a sequence of vicious competition and the irrational distribution of industrial capacity. The real solution to over-capacity is large-scale mergers and acquisitions.”[6]

In addition to furthering the industry-level goals of supply-side reform, Peng Jianguo notes that mergers can also help to readjust the overall distribution of state-owned assets in China’s economy. He says: “Currently, the structure of the state-owned economy is not reasonable: it is too dispersed and strategically overstretched, and duplication and even vicious competition are widespread. The overall structure must be adjusted as a matter of urgency.” Peng discusses the proper economic functions of SOEs and suggests that mergers should be used to concentrate state ownership in “important areas and key sectors that impact people’s livelihood and national security (such as basic and public industries), as well as prospective and pilot industries and sectors in which future competitive advantage could be formed (such as strategic emerging industries).”[7]

The State Council’s July 2016 “Guiding Opinions on the Restructuring and Reorganisation of Central State-Owned Enterprises” affirms this objective. The document adds a fourth reform target to the three targets from the September 2015 Guiding Opinions (the “cleaning up and exit of some state-owned enterprises, the restructuring and consolidation of some [through mergers], and the innovation and development of others”). This fourth target is “to fortify and strengthen a group of central state-owned enterprises” (巩固加强一批, gonggu jiaqiang yi pi), and the text puts it in first place—ahead of the previous three priorities. The new group is to comprise central SOEs in areas vital to the national economy and national security, including defence, nuclear power, basic communications infrastructure, power grids, oil and gas pipelines, and reserves of strategic materials such as oil and grain.[8]

Criticism of mergers

Some Chinese analysts criticised the September 2015 Guiding Opinions for giving a green light to the ongoing consolidation of SOEs. In an interview in the same month, Sheng Hong contradicted the common perception that mergers would strengthen Beijing’s control over SOEs by reducing the number of firms under central management. Instead, he argued that mergers would weaken the government’s position by creating increasingly large and powerful central SOEs:

“After mergers and acquisitions, the power of the monopolies will definitely increase, which will have no benefits for society, consumers, or private enterprises. The logic is very simple: as monopoly power grows, there are no alternatives to it, and there are even fewer methods to constrain it. After central state-owned enterprises are merged, it will be more difficult for the central government to control them, because it will be easier for the companies to oppose any challenge – like PetroChina and Sinopec, the National Development and Reform Commission and the National Energy Administration cannot control them, they are giants … If Li Keqiang were to face a single monopolistic Chinese oil company, his bargaining position would be very different than if he were to face three or five oil companies.”[9]

Others note that by increasing the size and complexity of state firms, mergers can exacerbate existing organisational problems, such as low efficiency, weak oversight, and communication gaps. Ju Jingwen highlights the need for readjustment in the internal resources of SOEs, especially within the largest enterprise groups. He advises “carrying out innovative adjustment of assets and organisations, focusing on solving the inefficiency and abuses that have long troubled enterprises as a result of business duplication and multi-tiered legal structures.”[10] Recent efforts to tackle these company-level issues include Li Keqiang’s ongoing “lean and healthy body” (瘦身健体, shou shen jian ti) reform initiative, which aims to trim central SOEs’ bulky organisational structures, and SASAC’s stepped-up audits of their domestic and overseas assets.[11] The State Council’s July 2016 Guiding Opinions also call for greater post-merger efforts to integrate management, business, technologies, markets, corporate culture, and human resources.

Mergers are a tool in the reform process, not its end goal

Despite critics’ fears, SOE mergers remain one instrument in a wider, evolving reform strategy; they are neither a cure-all solution nor the ultimate objective of reform. As Wu Jinxi says: “Restructuring is not an end in itself, but rather a means to give enterprises a higher platform from which to develop better and more quickly.”[12] Mergers have an important part to play in SOE reform, but they can prove counter-productive if used as a substitute for more painful reforms such as shutting down zombie firms. Wu says: “Quality and efficiency should be adhered to as the central aims, and restructuring must be viewed comprehensively rather than in isolation. Restructuring for the sake of restructuring is even more inadvisable.”

Others contend that the real issue in SOE reform is the transformation of the role of the state, not the restructuring of companies. Wu Jinglian argues that the state should step back from directly managing SOEs’ personnel, affairs, and assets. He says: “I think the most fundamental solution for state-owned enterprises is that the state becomes the owner of capital and acts as a shareholder in accordance with the Company Law.”[13] In an article in China SOE Magazine in 2015, Wu argued that power must be constrained by the rule of law, and that “structural obstacles” (体制性障碍, tizhixing zhang’ai) must be overcome to achieve economic transition.[14]

These perspectives evidence the range of views within China not only on the strategic aims of SOE reform and its methods, such as mergers, but also on the need for wider changes to the country’s legal, financial, and political systems. While government-directed consolidation continues to reshape Beijing’s portfolio of central SOEs, mergers are only one part of the broader and contested process of economic reform.

FOOTNOTES

[1] This article focuses on China’s central state-owned enterprises (中央国有企业, zhongyang guoyou qiye), specifically the 102 non-financial firms administered by the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC).

[2] CSR Corporation was previously known as China South Locomotive & Rolling Stock Corporation Limited, and China CNR Corporation was formerly known as China North Locomotive & Rolling Stock Industry (Group) Corporation.

[3] Li Jin, quoted in Zhang Ning and Wu Shi, “Reorganisation of Central State-Owned Enterprises Aims at Building One Belt One Road, Mergers to Result in Monopoly” (央企重组剑指一带一路建设合并或将导致垄断, yangqi chongzu jianzhi yidai yilu jianshe hebing huo jiang daozhi longduan), The Enterprise Observer, 31 March 2015, available at http://finance.sina.com.cn/chanjing/cyxw/20150331/130221853377.shtml. Li Jin is executive president of the China Enterprise Institute, vice president of the China Enterprise Reform and Development Research Council, and professor at the Central University of Finance and Economics.

[4] For the full text of the September 2015 “Guiding Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Deepening State-Owned Enterprise Reform” (中共中央、国务院关于深化国有企业改革的指导意见, zhonggong zhongyang, guowuyuan guanyu shenhua guoyouqiye gaige de zhidao yijian), see http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2015-09/13/c_1116547305.htm.

[5] The term “zombie firms” (僵尸企业, jiangshi qiye) refers to commercially unviable enterprises that are kept operational only by support from the government and banks.

[6] Li Jin, quoted in “Experts Talk About New Round of State-Owned Enterprise Reform: How Central State-Owned Enterprise Reorganisation Will Achieve 1+1>2” (专家学者畅谈新一轮国企改革:央企重组如何实现“1+1>2, zhuanjia xuezhe changtan xin yilun guoqi gaige: yangqi chongzu ruhe shixian “1+1>2”), The Economic Daily, 4 July 2016, available at http://www.sasac.gov.cn/n86302/n86361/n86401/c2415751/content.html (hereafter, The Economic Daily, “Experts Talk About New Round of State-Owned Enterprise Reform”).

[7] Peng Jianguo, quoted in The Economic Daily, “Experts Talk About New Round of State-Owned Enterprise Reform.” Peng is deputy director of the State-Owned Assets Research Supervision and Administration Commission Research Center.

[8] For the full text of the July 2016 “Guiding Opinions of the Office of the State Council on the Restructuring and Reorganisation of Central State-Owned Enterprises” (国务院办公厅关于推动中央企业结构调整与重组的指导意见, guowuyuan bangongting guanyu tuidong zhongyang qiye jiegou tiaozheng yu chongzu de zhidao yijian), see http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-07/26/content_5095050.htm.

[9] Sheng Hong, “Why Do I Reject This Round of State-owned Enterprise Reform?” (我为什么否定这次“国企改革”?, Wo weishenme fouding zheci ‘guoqi gaige’ ?), Unirule Institute of Economics, 15 September 2015, available at http://www.unirule.org.cn/index.php?c=article&id=3868. Sheng Hong is an economist at the Unirule Institute of Economics and a professor at Shandong University.

[10] Ju Jingwen, “The Reorganisation and Reform of State-owned Enterprises” (国有企业的重组与改革, guoyou qiye de chongzu yu gaige), China Thinktanks Network, 31 October 2016, available at http://www.chinathinktanks.org.cn/content/detail?id=3002886. Ju Jingwen is a researcher at the Institute of Economics at CASS.

[11] This reform mandates central SOEs to trim their organisational structures by 2020 through streamlining management and reducing the number of subsidiaries by at least 20 per cent. See “Li Keqiang Chairs State Council Executive Meeting” (李克强主持召开国务院常务会议, Li Keqiang zhuchi zhaokai guowuyuan changwei huiyi), The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 18 May 2016, available at http://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2016-05/18/content_5074482.htm.

[12] Wu Jinxi, quoted in Zhao Lingling, “Era of Central State-owned Enterprise ‘Combination’ Arrives But Reform Is More Than Structural Reorganisation” (央企“组合”时代到来结构整组并非改革初衷, yangqi ‘zuhe’ shidai daolai jiegou zhengzu bingfei gaige chuzhong), Sina.com.cn, 15 August 2016, available at http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2016-08-15/doc-ifxuxnak0302748.shtml. Wu Jinxi is director of the Center of Strategic Emerging Industries at Tsinghua University.

[13] Wu Jinglian, speech at the 2014 Forum China Automotive Industry Under the New Economic Normal, “Management of State-owned Enterprises Should Reorient to Focus on Management of Capital” (国企管理应转向以管资本为主, guoqi guanli ying zhuanxiang yi guan ziben weizhu), China Shipping Service, 21 May 2015, available at http://www.cnss.com.cn/html/2015/zhengquan_0522/177008.html. Wu Jinglian is a distinguished economist and former senior researcher at the State Council Development Research Center.

[14] Wu Jinglian, “Achieving Transition Still Requires Surmounting Structural Obstacles” (实现转型还需克服“体制性障碍”, shixian zhuanxing hai xu kefu ‘tizhixing zhang’ai’), China SOE Magazine, No. 12, 2015, pp. 68-71.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.