Three crises and an opportunity: Europe’s stake in multilateralism

Summary

- The multilateral system faces three related crises of power, relevance, and legitimacy.

- This fraying consensus threatens the EU, which is committed to multilateralism. But the situation also represents an opportunity for European influence.

- The EU should build coalitions to defend multilateral action in fields including trade; security and migration management; human rights; and controlling new technology.

- To succeed, the EU will need to take a pragmatic approach to forging multilateral coalitions, operating on a case-by-case basis and working with some unusual partners.

- The US, China, and Russia may all hinder Europe in this effort. Yet the EU will also need to overcome populist member states in its own ranks if it is to rebuild multilateralism for the 21st century.

Introduction

Multilateralism is in crisis; but the full nature of this crisis is still emerging. This is not – yet – a moment like the collapse of the Versailles order in the 1930s, when big power after big power walked out of the League of Nations. The United States has quit a series of multilateral arrangements since 2017. But it has not left crucial forums like the Security Council. This is not even a ‘new cold war’ situation in which tensions between powerful countries paralyse large tracts of the international system. By historical standards, this continues to be an era of extraordinary global cooperation, featuring an unprecedented quantity and range of multilateral arrangements and institutions. Donald Trump may not like the United Nations system. But he turns up at the UN General Assembly annually to register his complaints.

Nonetheless, this paper will argue that the multilateral system faces three connected crises. The first is a crisis of power, as global shifts in economic and political weight erode the bases of the system. The second is a crisis of relevance, as the UN and other global bodies struggle to handle old and new threats. The third is a crisis of legitimacy, as influential governments and angry populist movements question the values and ambitions that have grown up around multilateral bodies.

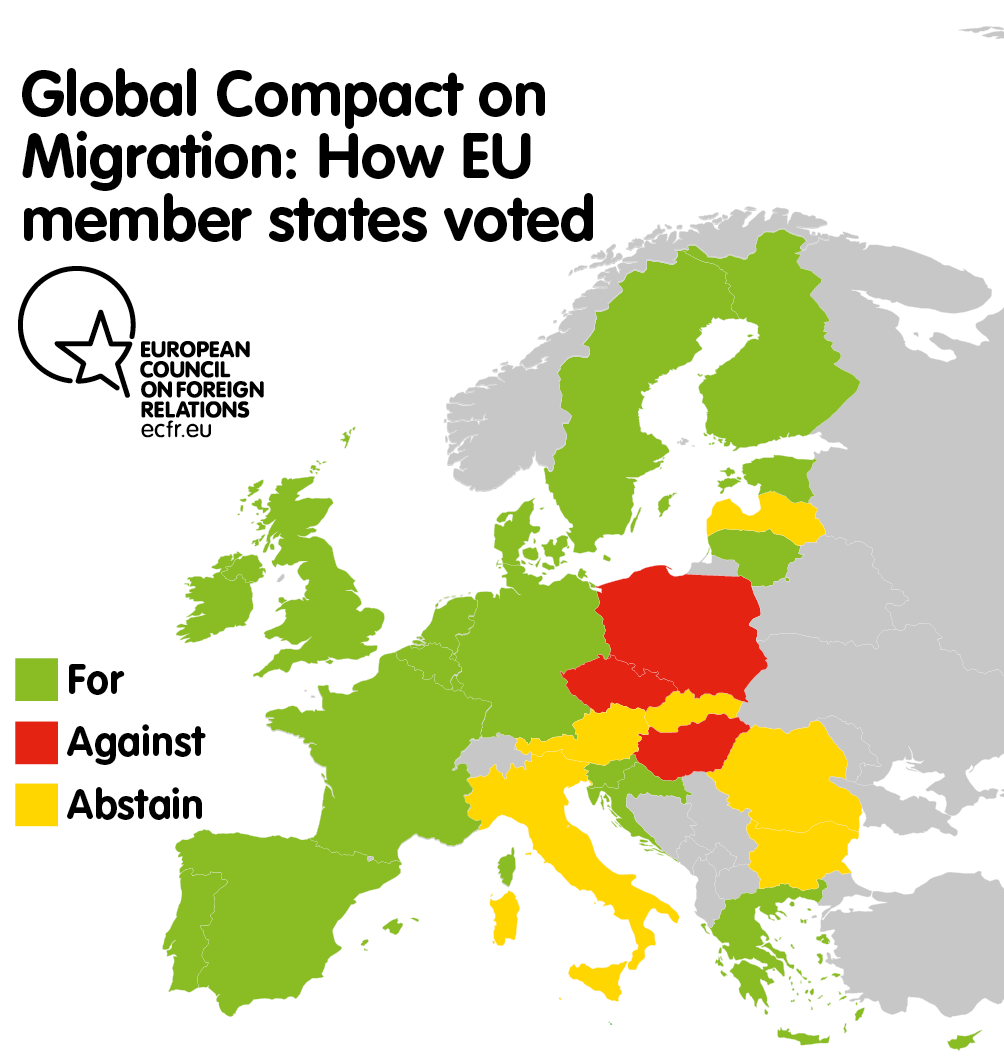

The members of the European Union are acutely aware of the three connected crises of power, relevance, and legitimacy. A decade ago, EU officials talked about “effective multilateralism” as an unbreakable article of faith. Since then, the EU has split badly over some significant multilateral initiatives, such as the 2018 UN Global Compact for Migration. And a small number of member states, particularly Hungary, have repeatedly disrupted EU positions in multilateral forums and created considerable frustration in Brussels.

But, despite its doubts and divisions, the EU remains the most consistent and best-resourced supporter of a strong multilateral system in the world today. Indeed, from a European perspective, this uncertain period also represents a moment of opportunity.

Europeans have many current and potential allies in their defence of a resilient international system. There are certainly many populist governments – such as those in Brazil and the Philippines – that admire the Trump administration’s rejection of internationalism. Yet there are many others that share Europe’s interest in a stable rules-based order, ranging from long-time multilateralists like Canada to developing African economies. These are not always absolutely ‘like-minded’ states in the sense of adhering to all liberal, Western positions. But EU members can still build cross-regional alliances on issues from cyber security to human rights. While the US and China compete for international influence, the EU could be a third pole in global affairs – if it can address the interconnected crises enervating the multilateral system.

Stung by the Trump administration’s voluble critique of international cooperation, leading EU members are now articulating a full-throated defence of institutions that they once took for granted. Even the United Kingdom, gradually if incoherently deserting the EU, is keen on multilateralism and European coordination in venues like the UN. This June, the European Council underscored its commitment “to strengthen rules-based multilateralism” with an “emphasis on facing new global realities”. And the incoming European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, insists that “we want multilateralism, we want fair trade, we defend the rules-based order because we know it is better for all of us.”

Individual members and subgroups of the EU have championed eye-catching initiatives to boost these principles, such as a call from Germany for an “alliance of multilateralists” with like-minded powers. In Brussels there is talk of deciding EU positions at the UN by qualified majority voting, and of bringing in legal penalties for EU members that fail to follow established EU positions in multilateral forums.

These proposals are important, but Europe’s multilateral influence relies on its ability to solve real-world problems through international institutions. This paper explores how the EU can do this in four areas: (i) international trade; (ii) security and migration management, with an emphasis on multilateral action in Europe’s peripheries; (iii) human rights; and (iv) the multilateral control of new technologies. This selection focuses on areas of multilateral activity where the EU has a capacity to innovate in multilateral systems, and other countries appear willing to work with it constructively. It naturally excludes many other significant multilateral issues, and does not concentrate on climate change, even though this is an all-important area for European action. This is because the basic UN-based frameworks and alliances enabling European action are fairly well-established. The paper’s focus areas offer immediate opportunities for the EU to strengthen its multilateral networks at a time when the international system is fragmenting.

Multilateralism’s three crises

A crisis of power

The two most severe challenges to the multilateral order today are the relative decline of American power, and the emergence of China as a rival power to the US in global organisations. The US has always been an ambivalent but essential guarantor of the international system. Its officials were pivotal in the design of the UN and Bretton Woods institutions in the 1940s and their rejuvenation at the end of the cold war. Both the Clinton and George W Bush administrations had tortured relations with the UN. But at moments of great global peril – such as the 2008 financial crisis – the US has stepped up to manage the response.

The US still has unrivalled power in most international organisations that matter (it is notable that the Trump administration has mainly quit bodies that do not institutionalise its primacy, such as the UN Human Rights Council). This preceded the current administration. Yet, over the last decade, there has been an observable decline in America’s capacity to shape multilateral affairs. Russia has opposed and outlasted the US in the Security Council over the Syrian war. China persuaded a significant number of US allies, including EU members, to help launch the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2015, against the Obama administration’s strong objections.

Despite the AIIB controversy, Barack Obama’s overarching strategy was to respect the shift in global power and try to mitigate it through multilateral arrangements. In the early 2010s, Washington hoped that it could find a UN-based solution to Syria, and it worked hard to keep China and Russia engaged in the Iranian nuclear negotiations. Perhaps most importantly, Obama worked successfully with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping to develop a joint front on climate change prior to the 2015 Paris climate summit.

The Trump administration has reversed course, and now sees multilateral forums as spaces to contest China’s rise in particular. Trump’s multilateral policy was initially quite confused: in his first 18 months in office, the president attacked at the Paris climate agreement and traditional Republican bugbears like UNESCO in a fairly haphazard fashion. But the arrival of John Bolton as national security adviser – and the concomitant decline of moderate voices such as former US ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley – has led to Washington adopting a more systematic approach to multilateral competition. In December 2018 secretary of state Mike Pompeo declared that China and Russia are “bad actors” in multilateral forums. The US representative at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has tied threats to undermine the body’s dispute resolution mechanism to China’s refusal to give up its protectionist and statist policies.

If the US sees China as a multilateral competitor, China has to some extent lived up to this perception since 2016. Diplomats, international officials, and analysts in New York and Geneva agree that the most striking feature of recent years has been a sudden Chinese push for greater influence in multilateral bodies. This is often more about symbolism than substance – Beijing seems to prioritise getting references to its Belt and Road Initiative into UN documents, for example. And it has sometimes pushed initiatives without considering the risk: the Chinese mission in New York has pressed hard to win greater influence over blue helmet peace operations, but it recoiled when Chinese troops died in Mali and South Sudan in 2016. There is sometimes a sense that Beijing has more ambition than strategy in multilateral affairs.

Nonetheless, it is pretty clear where US and Chinese policies will lead without some sort of course correction. A new bipolarity in multilateral forums, with the potential to weaken or halt their work, is likely to emerge. On issues from development to human rights, other capitals may have to decide whether their priority is to back Beijing or Washington in multilateral debates. To some extent, this is what multilateral forums are for. It would be sad if Sino-American contention complicated UN General Assembly diplomacy, but that is preferable to the two powers expressing their differences through military clashes in the South China Sea. As director of ECFR Mark Leonard has noted, Chinese experts predict that the new world order will be multipolar rather than bipolar, with middle and small powers swinging between the big two. Nonetheless, there is a serious risk that the next decade will see the freezing of multilateral diplomacy as China and the US face off.

This is not the only political threat to multilateral cooperation. Russia is an increasingly emboldened player in multilateral affairs, sometimes alongside China but sometimes solo. Regional powers like Saudi Arabia are also increasingly minded to challenge multilateral norms – this is part of the broader crisis of multilateral legitimacy described shortly. Overall, the world is moving from an era of US leadership in multilateral forums to one of confused multipolar competition.

A crisis of relevance

Even if big power politics were more harmonious, multilateral organisations would still be going through hard times. The UN, WTO, and other bodies are struggling to resolve both long-standing problems and emerging threats. Even policymakers from countries broadly sympathetic to multilateralism now talk about international institutions and their bureaucracies as an obstacle rather than an aid to achieving national policy goals.

This is partially due to the challenge (all too familiar to anyone who has worked on multilateralism for any time) of institutional reforms. Multilateral bodies are slow to change, and in some cases are still stuck with rulebooks and systems left over from the 1950s and 1960s. Reformers such as UN secretary-general, Antonio Guterres, and former World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, have pushed for change. But institutional inertia remains high and making even small reforms seems to involved excess grief and woe.

Furthermore, many organisations are essentially following agendas and mandates that no longer matter to a lot of states. The most obvious example is the international development business. Smartly targeted international aid is still important to fragile and deeply impoverished countries, and can help prepare developing states for climate change and other future shocks. But the days in which large-scale aid projects really mattered to most poor countries are at an end. China and other rising powers are able to offer investments with many fewer formal strings and bureaucracy attached than multilateral agencies. The global remittance industry accounts for over $450 billion of cross-border money transfers; this dwarfs aid.

Multilateral mechanisms are not keeping pace with either existing or new dilemmas facing the world in other fields, from crisis management to technology. For instance, UN-led mediation efforts have struggled across the Middle East and north Africa in response to the Arab revolutions. Multinational peace operations have become bogged down in cases like Mali and Somalia. European policymakers were shocked by the limits of UN agencies and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) at the height of the refugee crisis. But existing institutions and inter-governmental forums appear ill-prepared to handle new challenges too, such as how to govern cyber technology and artificial intelligence (AI). UN-based talks on cyber issues in particular have gone off track in recent years, in part due to big power splits. There has been marginally greater progress on robotic and autonomous weapons, but there is still a vast amount of work to do. Both the EU and UN leadership are pushing for serious discussions of AI, but major players including Silicon Valley and Chinese firms are wary of submitting to multilateral regulation.

A crisis of legitimacy

International entities’ weaknesses in the face of current challenges have fuelled a loss of faith in the multilateral system in many quarters. This takes many different forms. A number of globally ambitious middle powers – such as India and South Africa – are frustrated by their institutional disadvantages in international forums such as the Security Council. Regional players like Saudi Arabia (which took the unusual step of turning down a Security Council seat in 2013, citing UN inaction in Syria) and its allies have lost patience with the major powers that direct the UN over Syria and other crises. The Saudis’ faltering support for multilateralism has had disastrous ramifications for their intervention in Yemen.

Many increasingly self-sufficient African states are equally keen to be rid of multilateral oversight wherever possible. Ethiopia and South Africa, in particular, have attacked the Security Council’s management of their continent’s affairs. Many commentators in the past have tended to assume that democratic and liberal states will want to work with and through international institutions. But it now seems possible that states pursuing broadly liberal agendas may distance themselves from multilateral interference or, as in the African case, invest in regional political forums as alternative decision-makers.

The most striking challenge to the legitimacy of internationalist institutions comes, however, from nationalist and popular political movements. As EU officials are painfully aware, it is easy for demagogues

to demonise multilateral bureaucrats. In 2016, Trump devoted a good deal of campaign rhetoric to bashing NATO and the EU, and he has kept up his criticisms since taking office (Trump’s attacks on the UN, while serious, are more rooted in previous traditions of Republican politicians than his NATO-phobia). Meanwhile, Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, won office on promises to quit the HRC and Paris climate change agreement, although he has backtracked on these while still regularly criticising the UN.

Perhaps most disturbingly, inside the EU, populist governments and parties have made attacking multilateral institutions part of their brands. Hungary and right-wing politicians in Austria led a campaign against the UN Global Compact for Migration that eventually persuaded nine EU members to reject the pact. This even led to the collapse of the Belgian government. While migration is especially sensitive, European diplomats recognise that it reflects deeper rifts over the value and principles of multilateralism within the bloc. Outside powers like the US and China are increasingly trying to peel sceptical states like Hungary away from EU positions in international forums. Online trolls, often with connections to Russia, about international organisations among European publics.

Europe’s opportunity

Facing these three converging crises of multilateralism, it seems hard to believe that the EU can save the system. Yet for all its weaknesses, the EU may still emerge from this brewing multilateral storm unscathed, and even strengthened. There are three reasons for this.

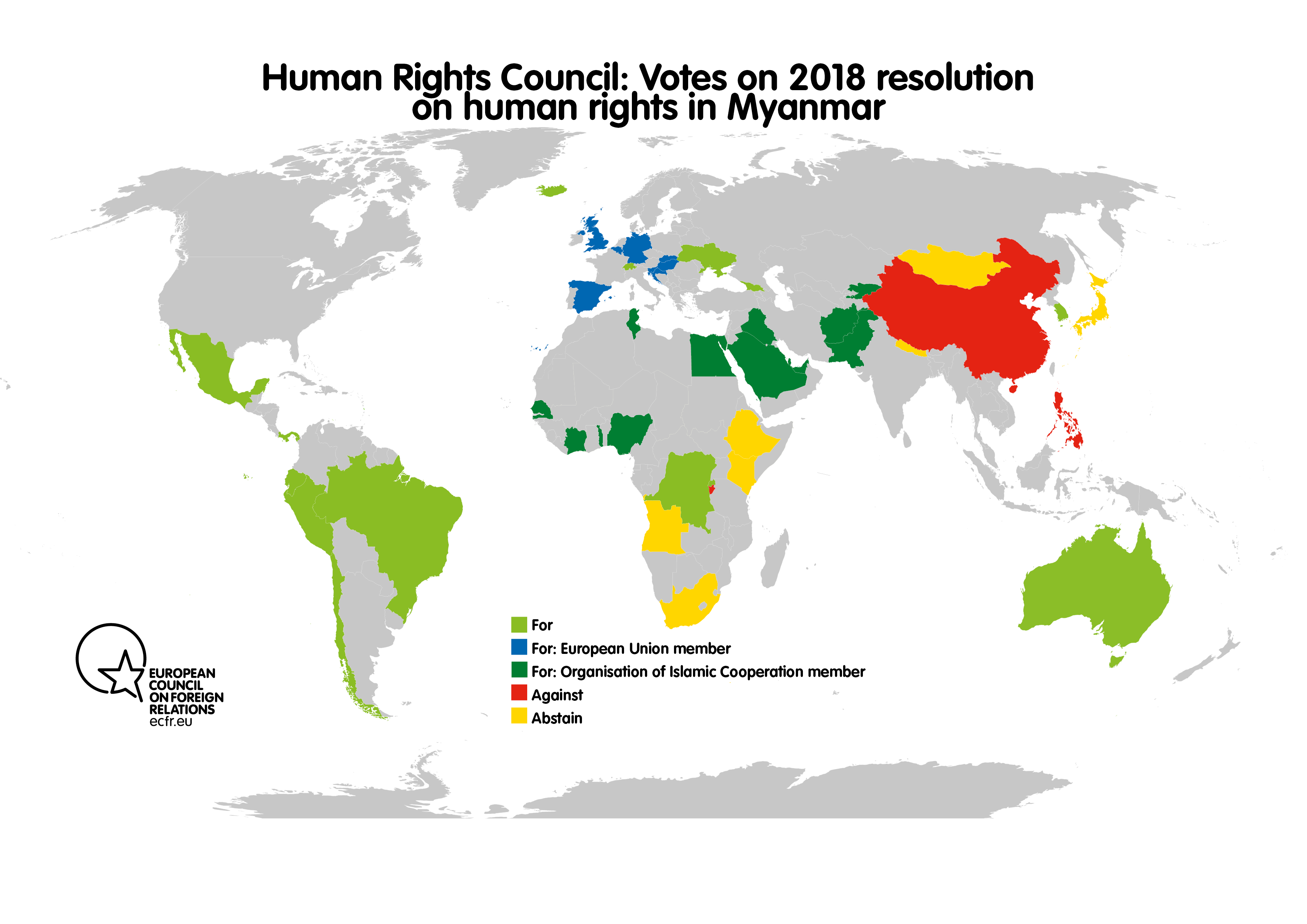

Europe is neither the US nor China

The first reason is that the current US turn against multilateralism has shocked a large number of states, many of which in the past would have instinctively distrusted Europe’s role in venues like the UN. This motivates them to work better with the EU than previously. Marc Limon of the Geneva-based Universal Rights Group points to the HRC as a paradigm for this trend.[1] When the US quit the HRC last year, some observers feared that non-Western states would aim to gang up on remaining liberal states and push proposals reversing past human rights advances. This was not an unreasonable concern: when the US boycotted the HRC between 2006 and 2009, illiberal states outvoted and outmanoeuvred the EU on many issues in Geneva, as ECFR chronicled at the time. But the EU has faced much less diplomatic pressure this time. Traditional opponents of Western positions, such as Pakistan and the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC), are now working much better with the EU on perennially difficult problems like religious intolerance and freedom of religion, as well as on important country situations such as Myanmar. This suggests that the EU – as a comparatively stable ally of multilateralism – may gain from US disengagement.

It is also notable that many non-Western powers are wary of China’s newfound assertiveness in multilateral forums. This also creates political space for the EU. Some African members of the UN have, for example, been worried by China’s increasingly high-handed approach to the organisation’s peacekeeping budget (of which the country pays a growing share). Conversely, Chinese diplomats are keen to work with the EU to counter disruptive US policies in organisations such as the WTO. Overall, the looming threat of a new Sino-American bipolarity in multilateral affairs counter-intuitively advantages Europe. In contrast to others, the EU starts to look like a third, more attractive, pole of influence in international organisations, one committed to sustaining global cooperation.

Europe’s skills can keep the show on the road

Second, European diplomats have the technical multilateral skills necessary to keep the system running despite the disruptive behaviour of the US and other big powers. European officials have always taken on an outsize proportion of process management duties in the UN and other international forums. One European diplomat based in New York estimates that EU members have a chairing or convening role in roughly four-fifths of UN negotiation processes (normally in tandem with a non-European power). In the past, the main motivation for this work was to take some international burdens off Washington, and hopefully win some US favour in the process. Now EU members are taking on technical responsibilities for multilateral diplomacy either in the absence of US leadership or in the face of American scepticism.

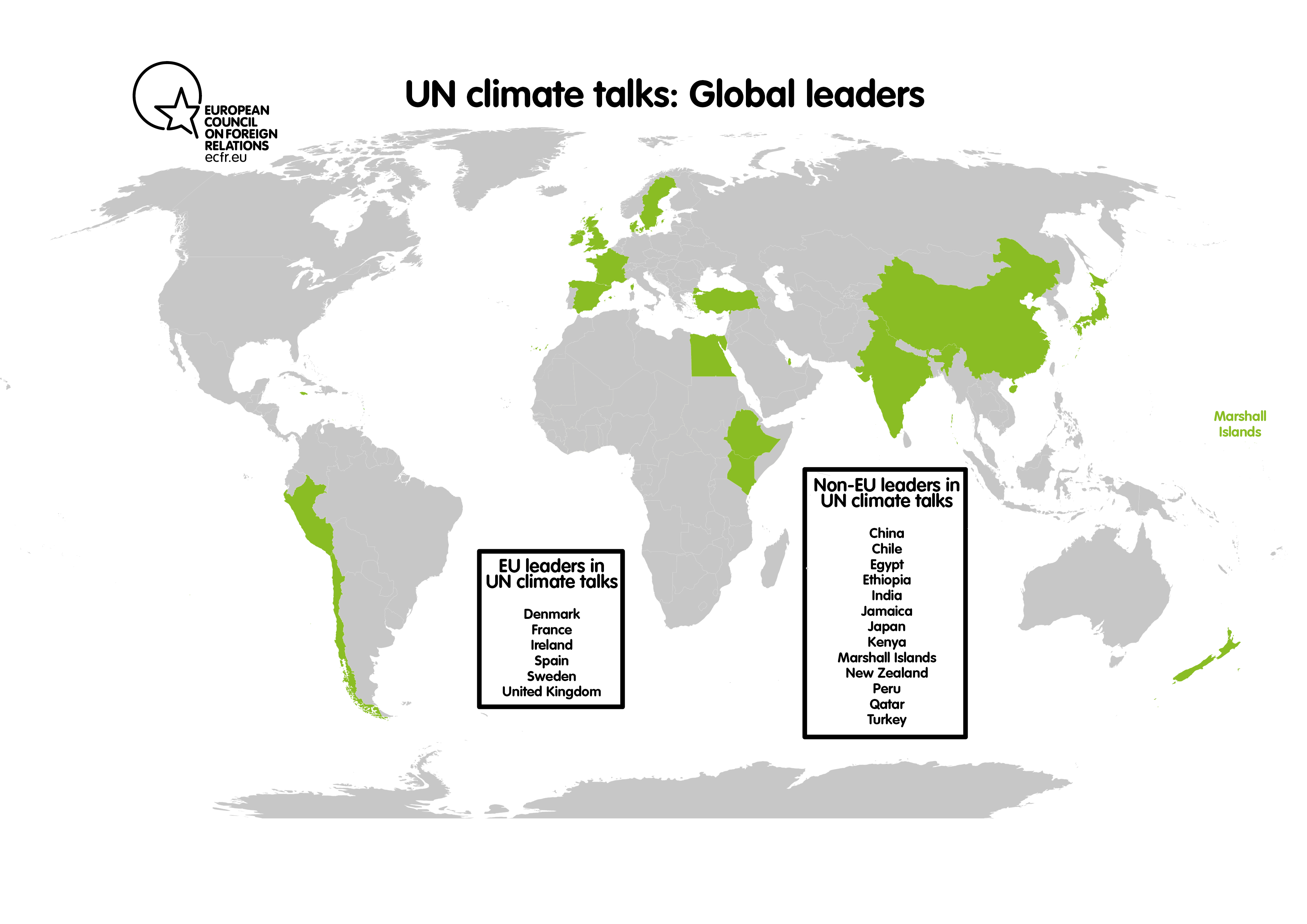

Climate change policy offers a good example of this shift. In the run-up to the 2015 climate summit, EU members and the Obama administration worked in close coordination to bring the Paris agreement into being. The two sides had a strong sense of comparative advantage: the US concentrated on bringing China on board, for example, while Germany worked on Russia. Now, as the US has disengaged from post-Paris climate diplomacy, the Europeans need other partners. The UN is, for example, currently preparing for a Climate Action Summit in September 2019, with a focus on new commitments to reduce carbon emissions. EU members are involved in leading six of the nine policy tracks leading up to the summit, ranging from mitigating the effects of climate change to addressing its social consequences. The US is absent, but other major and middle powers – including China, India, Egypt, and Ethiopia – are working alongside the Europeans and UN officials on the summit. There is no guarantee that this event will have a transformative role in implementing the Paris deal. If the US continues to stand aloof in international settings in the future, the diplomatic format of EU and non-Western powers sharing leadership may be the pattern of future multilateral engagement across other policy areas. China and India have, for example, also supported EU-led efforts to protect the WTO from US pressure over the last year, despite policy differences over trade questions.

European leadership is not universally welcome in international bodies. Beijing won a rough campaign to ensure a Chinese candidate beat a French rival to lead the Rome-based Food and Agriculture Organization. There has been widespread criticism of the EU’s grip on the directorship of the International Monetary Fund this year, as European candidates have tussled to replace Christine Lagarde in Washington. Only a fairly small number of EU members, such as France and the Nordic countries, prioritise their missions to international institutions. Many diplomats fret that the loss of British expertise to the EU will be a problem at the UN in particular. Nonetheless, the EU’s members still have enough collective expertise – buttressed by the European External Action Service – to manage multilateral processes better than most.

Europe is already innovating

The third reason that they may benefit from the crisis of multilateralism is that Europeans have already begun devising new ways to strengthen the multilateral order. This has taken two main forms to date: European leaders and diplomats have been keen to promote new coalitions and caucuses in support of multilateralism – some solely involving EU members and others with broader scope; and they have also identified new policy areas for multilateral cooperation, such as cyber security.

The most prominent examples of the former tendency include Germany’s launch of an “Alliance of Multilateralists” – backed by France – which aims to bring together partners such as Mexico, Canada, and South Korea “to stabilize the rules-based world order, to uphold its principles and to adapt it to new challenges where necessary.” This new mechanism is still to engage in promoting specific policies, and European officials say that it is likely to be more of an open-ended network than a tightly defined alliance – inviting different configurations of non-European states to cooperate on particular – but the basic idea has attracted a good deal of diplomatic and media attention as a counter to mounting US unilateralism.

In addition to this nascent alliance, examples of European governments encouraging multilateral innovation include: France’s Paris Peace Forum, launched last November, which Emmanuel Macron has promoted as a laboratory for new thinking on global cooperation; and a new drive for European coordination in the UN Security Council. As a member of the council in 2018, Sweden launched a series of joint statements by existing and incoming European members of the council under the banner of the “EU8”, boosting the EU’s status in New York. This group has now morphed into an “EU6” and remains quite active (it comprises Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Poland, and Estonia; the last will replace Poland as eastern Europe’s representative on the council next year). Although these EU-flagged groups have no formal status in the UN or EU systems, they have nonetheless managed to make European positions heard more clearly on issues like Syria and Palestine in New York than in the past. The UK has been a consistent participant, and has signalled its desire to stay close to the EU in UN affairs after Brexit.[2]

More concretely, EU member states and institutions are grasping that they may be well placed to address the multilateral system’s weakness in the face of new technologies like AI. As a huge market with strong regulatory frameworks, Europe has the power to formulate – or at least significantly influence – the governance of digital and other innovations. The rollout of the European Commission’s 2018 General Data Protection Regulation was a source of enormous irritation to anyone with an email inbox, but it showed the EU’s reach as corporations worldwide (including in the US) ensured that they met EU privacy standards.

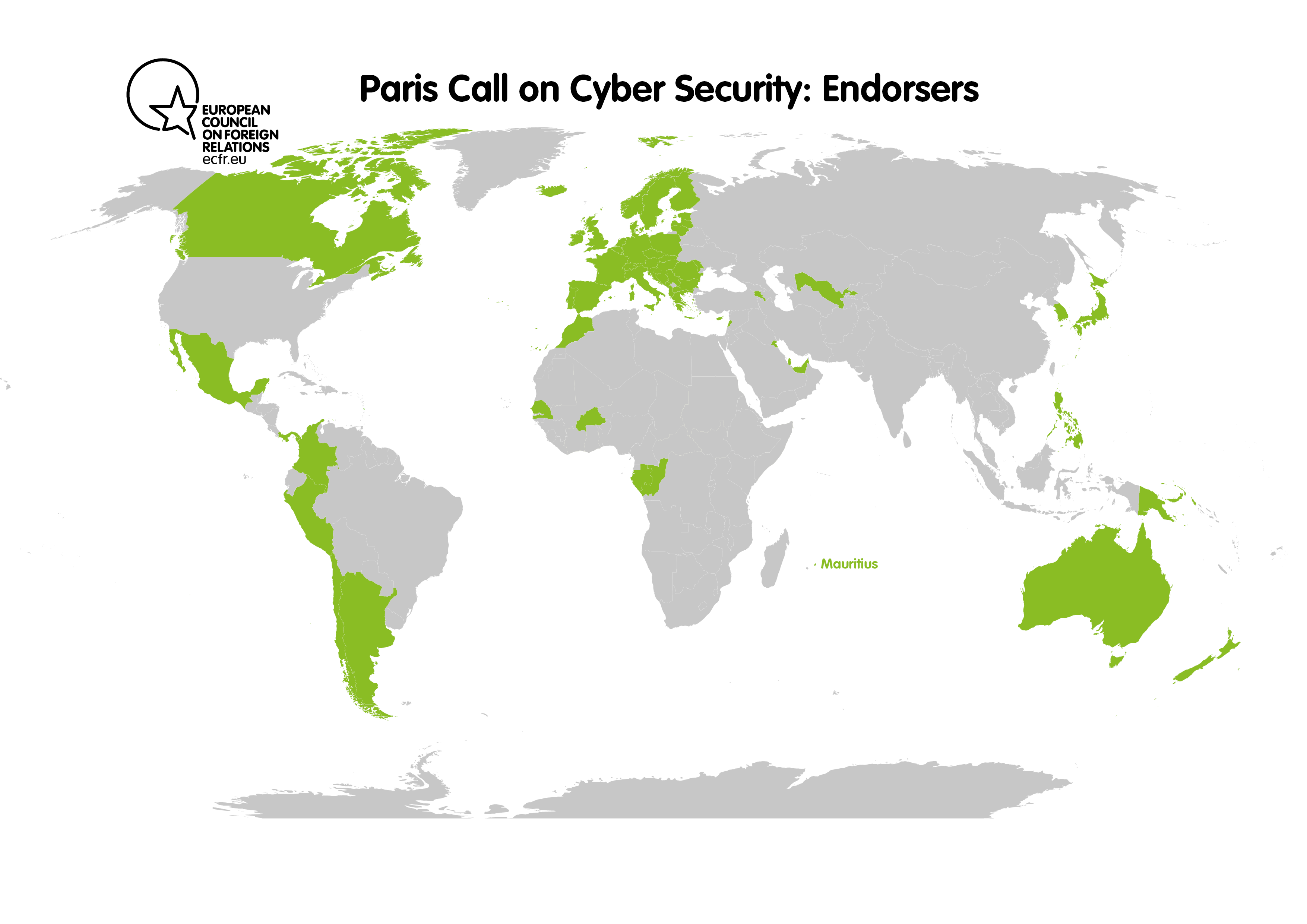

For example, the European External Action Service and technologically minded states such as France and Finland are working hard to lay out fresh thinking on AI in particular, again linking to other liberal countries such as Canada. Give the multiple applications of AI to economics, security, and information, the EU’s focus on this realm gives it the potential to play a huge role in emerging global governance arrangements. There is evidence that other powers will accept European leadership on technical matters. As part of the first edition of the Paris Peace Forum last year, France launched a “call for trust and security in cyber space” (the Paris Call). This comprises guidelines for reducing the risks of cyber espionage and cyber warfare and has won support from all EU members, 39 non-European states, and over 300 tech companies. The non-European, non-state signatories did not include China, Russia, or the US, but did include significant middle powers such as Australia and Japan.

Analysts based in these middle powers see a market for further collaboration with the EU. For example, Roland Paris is a Canadian academic and former adviser to Justin Trudeau who has explored the Alliance of Multilateralists concept. He argues that it is “fanciful” to imagine that liberal powers can save the international system without some Chinese and US support, but he does allow that “if these countries worked together in a concerted campaign, they might succeed in slowing the erosion of the current order, or perhaps even strengthen and modernise parts of it.” This is a realistic basis for identifying multilateral arenas in which European states – and the EU collectively – should invest more political attention. Equally, the EU’s multilateral partners need not only involve the usual suspects among the middle powers. The EU’s networks may also range from security partners such as African countries fighting terrorism to Islamic states united in concern by the persecution of Rohingya in Myanmar. These do not always fit into the established category of like-minded states with which EU members normally work comfortably in multilateral institutions. But they can address specific and immediate challenges.

Four areas for multilateral action

There are several areas in which the EU may be able to halt the erosion of current institutions. The remainder of this paper looks at four where European action is either urgent, promising, or both: at the WTO; in security and migration management; on human rights; and the control of new technologies. In each case, there is no guarantee that the EU will be successful, even with strong networks of allies. But it is improbable that coalitions of other states can resolve these problems if the EU’s members stand aloof.

International trade

International trade has become the most active front line in the battle over multilateralism. The rules-based trading system centred on the WTO has come under increasing strain of late: the shape of international trade has been transformed in recent decades by the growth of digital commerce and the development of information-based value chains. This has raised questions about the effectiveness of the multilateral system but new rules to respond to this have not emerged at the WTO. At the same time, China has taken a leading position in world trade while preserving an economic and political system that differs fundamentally from the Western liberal democratic and market-orientated model. This has led critics to argue that China is exploiting the WTO system to profit from a structurally unlevel playing field.

Since Trump took office, these long-term strains have turned into a full-blown crisis. Trump’s administration has taken a series of actions that together represent a fundamental challenge to the multilateral trade system. Building on US concerns about the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism that predate Trump’s election, the administration has blocked appointments to the organisation’s Appellate Body. This threatens to paralyse the operation of dispute settlement by the end of this year. The administration has also imposed tariffs on steel and aluminium under the WTO’s national security exception, a move that most trade experts regard as an abuse of the system that could set a disastrous precedent. And the US responded to alleged Chinese malpractices by imposing sweeping unilateral sanctions outside the WTO system, throwing the world’s two largest economies into an escalating trade war.

EU member states share many of the concerns about Chinese economic practices that have motivated many of these US moves. But they believe that the best response would be to confront China within the multilateral system and work to update its rules where necessary. In principle, the EU should be well placed to act as an intermediary between the US and China, drawing on the support of other leading trading economies like Canada and Japan, and Latin American countries. The EU could encourage the US to go beyond the complaints for violations of specific rules that it has made against China through the WTO so far and join the EU and other countries in filing a comprehensive collective case, as some US trade experts have recommended. The EU could also seek to draw China into reform of WTO rules in areas like subsidies, state-owned enterprises, technology transfers, the definition of developing countries, and transparency. These issues were all addressed in the concept paper on WTO reform that the EU released in September 2018 and are central to the trilateral discussions between the EU, US, and Japan.

Nevertheless, there are a number of obstacles to any swift resolution of the problems affecting the multilateral trading system. It is questionable whether even a comprehensive case against China would succeed in addressing many of the economic practices that are most troubling to its partners, as these do not clearly violate existing rules. Where they may violate rules, this can be difficult to prove. At the same time, China is likely to resist any proposed WTO reforms that would require it to undertake deep structural reform of its economic system.

The prospect that China might agree to at least some reforms to end the trade war with the US is complicated by a fundamental uncertainty inherent in stated US objectives. Some officials in the administration, and indeed many other politicians in Washington, see China’s economic development through the lens of strategic competition. This is in line with the administration’s mantra that “economic security is national security”, elaborated in the 2017 National Security Strategy. However, Trump at times gives a contrary impression, implying that he is willing to instrumentalise security measures for more narrowly economic objectives, such as when he announced the relaxation of US restrictions on Huawei as part of the resumption of trade negotiations in June 2019. A united front between the EU and US will require a much clearer distinction between issues of security, where Western and Chinese interests are fundamentally opposed, and an economic sphere, where Western capitalist economies and the Chinese state-centred economy can still benefit from trade relations, even if the process of agreeing fairer rules for their interaction is not straightforward.

It will also require the US to renew its commitment to the multilateral system in a way that this administration has not yet done. The dispute settlement mechanism is a cornerstone of the WTO system. The EU has suggested a series of reforms that go some way to meeting US concerns about the organisation’s Appellate Body, but the US refused to engage with European suggestions. This raises the question of whether Washington is interested in finding a solution or whether it prefers to see the dispute settlement mechanism paralysed, returning the multilateral trade system to “a power-based free-for-all, allowing big players to act unilaterally and use retaliation to get their way”, in the words of three prominent trade economists. To satisfy the US, the EU and other WTO members may have to consider reforms that shift the balance of power back towards WTO members from the Appellate Body in cases of legal uncertainty, by referring issues back to committees made up of member states. In the meantime, the EU is likely to have to try to implement an interim solution to allow dispute settlement to continue in the absence of a functioning Appellate Body, such as a proposal it recently circulated that would see consenting states refer appeals to ad hoc panels composed of retired WTO judges.

Security, migration, and human protection on Europe’s southern periphery

When it comes to crisis management and human suffering, some of the most urgent challenges to multilateral cooperation are playing out on Europe’s periphery. These include the conflicts in the Arab world and the Sahel, and the related challenges of transnational terrorism and unregulated people flows in the Middle East and north Africa. To mitigate the chaos, the EU’s members have backed UN and locally led mediation efforts and peace operations from Mali to Somalia, in addition to the work of international aid agencies. Nonetheless, EU members have also been complicit in programmes that have made the situation worse in some cases. European aid has gone to ill-disciplined security forces and militias that have detained and abused migrants in Libya and its neighbours. France and Italy’s competition for political influence in Libya has made the UN’s efforts to reunite the divided country harder. The fact that the EU was unable to unite in support of the UN Global Compact on Migration in 2018 highlighted its lack of unity over how to tackle crises unfolding to its south.

Still, EU members’ efforts to manage the crisis in the Sahel through multilateral means – such as deploying peacekeepers to serve under UN command in Mali – creates a basis for further much-needed multilateral stabilisation efforts in the region. The EU has helped launch the G5 Sahel Joint Force (a counter-terrorist operation involving Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Chad) and funded UN human rights officials to monitor and improve the mission’s treatment of civilians. While France remains the decisive EU player in west Africa in particular, Germany has become heavily engaged in assistance to both the Sahel and Sudan. The European Commission has managed a project on migrant protection with the IOM in the Sahel since 2016 that has saved the lives of some imperilled migrants and helped others return home. But the EU may need to double down on its engagement in Africa: the recent coup in Sudan and jihadi violence in across large parts of the Sahel suggest that there is more instability ahead.

Enhanced EU engagement with north Africa and the Sahel will have to involve working with the EU’s established regional partners – including the members of the G5 Sahel, Economic Community of West African States, and the African Union – to improve security provision across the region. But it should also involve efforts to boost government services, strengthen human rights monitoring, and provide increased assistance to vulnerable migrants and refugees as elements of a longer-term approach to stability and reducing the unregulated flow of people to Europe.

In the security field, the first priority for European donors should be to provide additional assistance to UN and local forces battling rising violence in Mali and Burkina Faso. This should not, however, involve solely military support but also include financing for local conflict resolution work and following UN guidance to rebuild institutions affected by war, such as schools. Over the longer term, the EU needs to systematise its security relationship with the G5 Sahel – to date the European institutions and EU members have tended to offer funding for its operations in a haphazard fashion, and France has pushed for the UN to pay for it instead. The US has blocked the latter proposal, partly on cost grounds but also out of justifiable concerns about African forces’ human rights and discipline records.

While continuing to explore the UN option, EU members should work out a new mechanism that offers the G5 Sahel more predictable European funding going forward, and ties this to expanded European training, building on existing programmes in Mali and Niger, and to in-depth UN human rights monitoring of its operations. As ECFR’s Andrew Lebovich has noted, planners in Brussels have already worked up proposals for a civilian Common Security and Defence Policy mission focused on improving coordination with the G5 force (although there is a risk that this would add complexity to the EU’s already convoluted array of missions in the area.) EU members have provided logistics support to the UN in Mali and French-led counterterrorist operations in the region, and therefore could offer logistics help for G5 forces.

In parallel with these efforts, EU members need to review and reinforce their approach to migration and refugee management across the Sahel. Despite the amount of money the EU has invested in addressing the problem, Lebovich underlines that it has not always it spent wisely, such as occasions it has financed security crackdowns to block migrant routes that alienated and impoverished local communities. This has fuelled public grievances with the EU’s role and pushed migrants to risk increasingly dangerous routes to Europe. Militia forces funded by the EU have been. Working with the IOM, UNHCR, and other aid agencies the EU should overhaul its dealings with the G5, Sudan, and other transit countries to minimise these abuses.

Focusing on these issues is not only a humanitarian necessity, but would also be a way for EU members to show fidelity to the principles of the Global Compact for Migration – and the parallel Global Compact for Refugees, also agreed in 2018 but with less controversy – without reopening all the arguments that surrounded the UN process. It is hard to see how EU members that refused to sign the compact, including Italy, could do so now without losing face politically, even if would be the right thing to do morally. But a focused, cross-EU effort on improving the conditions of migrants in the Sahel alongside security assistance could heal diplomatic wounds.

Human rights

In the years after 1989, many Europeans believed that reform of the international system could give a greater place in it to human rights. These years saw the development of international justice leading to the creation of the International Criminal Court, the elaboration of the Responsibility to Protect, and the establishment of the HRC in 2006. Today it is clear that a multilateral order that strongly and consistently supports human rights has not transpired. Instead, European aspirations to uphold international norms through the multilateral system face a competitive environment in which trade-offs and coalition-building are required.

Recent votes in the HRC show the challenges but also the opportunities of the contemporary international order. China in particular has made a concerted effort in recent years to shape the international discourse on human rights in a way that reflects its sovereignty-orientated vision. It succeeded in passing two significant thematic resolutions: one in 2017 endorsing the importance of development for human rights, and one in 2018 that backed “mutually beneficial cooperation” on human rights.

Yet EU member states have also been able to achieve impressive results by forging alliances with new partners, a process that the withdrawal of the US from the HRC may have made easier.[3] In the wake of the US withdrawal, European countries teamed up with the OIC to pass a resolution setting up an investigative mechanism on the persecution of the Rohingya in Myanmar. They also supported Latin American countries on a resolution on the crisis in Venezuela that was harsher on the Maduro government than the EU might have risked alone. This year, European states pushed through a call for the UN to investigate extra-judicial killings of alleged criminals in the Philippines, although Hungary opposed this.

There are limits to this type of cooperation: this summer EU members and their allies failed to persuade any member of the OIC to sign up to a letter to the HRC on China’s persecution of the Uighur minority. A number of OIC members signed a counter-letter supporting Beijing’s policies. The HRC is a transactional body. But, where interests converge, the EU can use Geneva as a platform for pragmatic cooperation.

By contrast, the Security Council has been a particularly difficult forum for supporting human rights because of the Russian and Chinese vetoes. Russia and China have consistently blocked efforts to condemn atrocities in Syria or refer the situation there to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Even on a procedural vote on allowing the high commissioner for human rights to brief the Security Council on atrocities in Syria, China was able to defeat the resolution through effective lobbying of African members of the Council to abstain. And the US recently shocked European countries by using the threat of a veto to force the removal of language on sexual and reproductive health from a resolution on sexual violence in conflict. By contrast, the General Assembly has been a more promising forum for action on human rights in Syria: it established an independent mechanism to investigate atrocities there in 2016, with the backing of the outgoing Obama administration. However, with the US pulling back its support for human rights within the UN system, China and Russia have succeeded in cutting funding for human rights positions in recent years.

The conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and Sudan have seen an apparent disregard of fundamental principles of international humanitarian law, including indiscriminate attacks against civilians and the widespread targeting of hospitals. Hopes that the ICC might usher in a new era of accountability were, in retrospect, clearly overstated. Even where it has jurisdiction, the ICC has faltered of late. In a series of high-profile cases arising from Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, the court has proved unable to successfully prosecute influential political figures. In a troubling recent decision, its pre-trial chamber ruled that investigations in Afghanistan would not serve the interests of justice, apparently bowing to the prospect of US opposition and undermining the strategy of the court’s chief prosecutor.

The ICC’s problems and internal disagreements suggest that it would be helpful for the Assembly of States Parties (ASP) to launch a review of the court’s operations and the best way for states to support it, as a group of former ASP presidents recently suggested. The way forward is likely to involve a reduction in expectations about what the ICC can accomplish, at least in the short term. It may be best to think of the court as a body primarily for investigating cases in countries that have accepted its jurisdiction, and to try to improve its operations and the support it receives in such cases. Since EU member states have been among the court’s strongest supporters, it would make sense for them to initiate discussions with potential partners about setting up an ASP review.

Overall, EU members are likely to make most impact in multilateral human rights forums if they are willing to be pragmatic and – as in the push to corner Myanmar in the HRC last year– coordinate with countries they often disagree with to address specific crises where their interests converge. European diplomats agree that there is a need to “rethink like-mindedness” in such situations, focusing on specific wins despite differences over wider principles.[4] This may involve hard compromises: EU members have worked with Saudi Arabia to condemn human rights abuses in Syria in the past, despite Riyadh’s own frequent disregard for UN conventions and international humanitarian law. But UN human rights forums will have even less impact if the EU cannot forge such necessary bargains.

Controlling new technologies

While the challenges facing the EU in trade, security, and human rights are all severe, it is the technological sphere that may decide the long-term future of multilateral cooperation. There are currently few robust international mechanisms for control of cyber technologies and AI, and equally few clear diplomatic pathways to addressing this. As cyber and AI expert Eleonore Pauwels has warned, “at a time of technological rupture, the risks of global insecurity are heightened by trends of isolationism and lack of collective responsibility.” While some EU members, including the UK and France, have invested in weaponising new technologies, the bloc broadly agrees on the need for some international framework to control them. But multilateral organisations like the UN struggle to influence powers like China that do not wish to submit to real limits to their technological capacities, and private American firms that dislike regulation. This has extraordinarily negative potential consequences in fields from economic inequality to privacy rights and arms control. As ECFR’s Ulrike Franke observes, the EU’s ability to shape diplomacy in the AI field appears limited due to its relative shortage of tech champions.

Nonetheless, the EU does have at least three potential advantages in engaging in technological diplomacy. The first, as suggested above, is that the EU appears to be a relatively impartial – or at least non-threatening – referee in strategic fields that China, Russia, and the US could otherwise dominate. This makes it a natural convener of discussions of the rules of the road in the cyber and AI domains, as the wide support for the Paris Call on cybersecurity indicated. Even the Trump administration, facing AI competition with Beijing, recognises that it needs to work with its allies in this field occasionally. In May 2019, the US signed up to a new set of OECD recommendations for “values-based principles for the responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI”. In June 2019, the G20 also endorsed a set of principles based on the OECD model. Given the EU’s collective weight within the OECD, this shows how European governments can still affect global debate around technological issues – although it is fair to ask, and hard to know, if American and Chinese military planners will really respect either the OECD’s or the G20’s declarations on AI.

Secondly, as Franke notes, the EU’s views on AI carry weight due to its status as a “regulatory superpower” and the bloc’s willingness to talk about the need for an ethical approach to the field. The European Commission – along with Germany and other EU members – has been calling for more discussion of the ethics of AI in recent years, and they have the ability to leverage the size of their market, challenging social media firms and spreading GDPR standards outside Europe. Even if European firms are not leaders in all technological areas, Europe’s power as a market still gives it political heft.

Finally, the EU can help legitimise its efforts to bring some degree of order to technological competition by appealing to those countries with most to lose from it – poor and developing states with little technological base of their own. Pauwels predicts that “forms of cyber-colonization are increasingly likely, as powerful states are able to harness AI and converging technologies to capture and potentially control the data-value of other countries’ populations, ecosystems and bio-economies.” Poor governments, not least in Africa, lack the resources to prevent such takeovers. But if the EU is able to reach out to them in forums such as the UN, it may be able to build a wide group of states to back its positions on technological issues as a counter to those powers – perhaps especially China – that wish to take control of their data.

For the time being, the EU has a considerable amount of work to do developing a common understanding of technological challenges and how to address them. Franke suggests that this will involve “rapidly educating [European] citizens and policymakers, as well as substantially increasing investment in AI and carefully choosing which subfields of AI to fund.” If it succeeds in this, the EU could be a central player in multilateral technology issues.

Conclusion

There are many obstacles to the EU achieving its goals in multilateral forums. The US has the leverage to undercut European initiatives in many ways – from using its institutionalised privileges in multilateral forums like the Security Council, to driving wedges between EU states. Meanwhile, China may refuse to bargain away its advantages in fields such as AI or the international trade system. In some cases, European efforts to rouse other countries to support its initiatives could actually backfire, causing the US, China, and Russia to unite in opposition to multilateral constraints – just as the three powers have refused to consider any limitations to their right of veto in the Security Council, including proposals from France to this end, despite the fact that they use these vetoes to frustrate each other.

Nonetheless, the EU is most likely to defend its interests in the multilateral system if it builds alliances where it can, and this paper has shown that there is some market for its diplomatic efforts. This does not mean that the EU can establish a tight ‘European bloc’ across multilateral forums. While some liberal middle powers are likely to side with the EU on many issues, few can be expected to unite with it all of the time. Canada has been enthusiastic about the “Alliance of Multilateralists”, for example, but it has had to soft-peddle this at times to protect its trade relations with the US. Japan may approve of European initiatives in the cyber realm, but it last year refused to back an HRC call for an investigation into the Rohingya crisis, reflecting its Asian diplomatic interests. Many of the Muslim-majority countries that did back that call continue to disagree with the EU over other human rights resolutions across the UN.

EU coalition-building in multilateral forums will, therefore, remain case by case and sometimes haphazard. Nonetheless, the greatest threat to the EU as a multilateral actor remains internal.

The emergence of strong anti-internationalist forces in Europe – and of governments like Hungary’s that are willing to give voice to populist views in multilateral debates – could well stop the EU playing a balancing role in today’s turbulent global order. There have been a number of proposals in Brussels to limit spoilers’ ability to disrupt EU positions, but as yet neither the EU institutions nor big European member states have been willing to make serious threats to Budapest or other recalcitrant capitals over their behaviour in international institutions. It may eventually be necessary for liberal, outward-looking members of the EU to ignore these spoilers and work as a pro-multilateral subgroup of European states on some issues. Yet the biggest challenge of all is not among states and diplomats but among publics: European policymakers need to persuade voters that helping migrants, or worrying about human rights in Asia, are still their concern. Many countries around the world are looking to the EU for partnership to navigate the current crisis of multilateralism. European leaders need to have the political courage to do so at a time when strong forces are pushing them to worry less about the world.

About the authors

Richard Gowan is an associate fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is currently UN director at the International Crisis Group, and was previously research director at New York University’s Center on International Cooperation. He has taught at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and Stanford in New York, and wrote a weekly column on multilateralism (“Diplomatic Fallout”) for World Politics Review from 2013-2019. He has acted as a consultant to the UN on peacekeeping, political affairs, and migration.

Anthony Dworkin is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He leads the organisation’s work in the areas of human rights, democracy, and justice. Among other subjects, Dworkin has written on European and US frameworks for counterterrorism, the European Union’s support for transition in north Africa, and the changing international order. He is also a visiting lecturer at the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po.

Acknowledgements

The authors shared a very early version of this paper at a conference in Mustio, Finland, in February 2019 organised by the Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA) and the Finnish ministry of foreign affairs. The authors would like to thank Teija Tiilikainen and her team at FIIA for an excellent discussion. In the ministry, Janne Jokinen and Sini Paukkunen have been generous and patient friends of this project. We also thank Marc Limon, Adam Lupel, Megan Roberts and a number of European officials and diplomats for their advice at various stages of our writing.

Footnotes

[1] Telephone conversation between author and Marc Limon, January 2019.

[2] Private conversations between author and European diplomats based in New York, 2018-2019.

[3] This point was made to the authors by Marc Limon, January 2019.

[4] Private conversation between author and a European ambassador, September 2019.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.