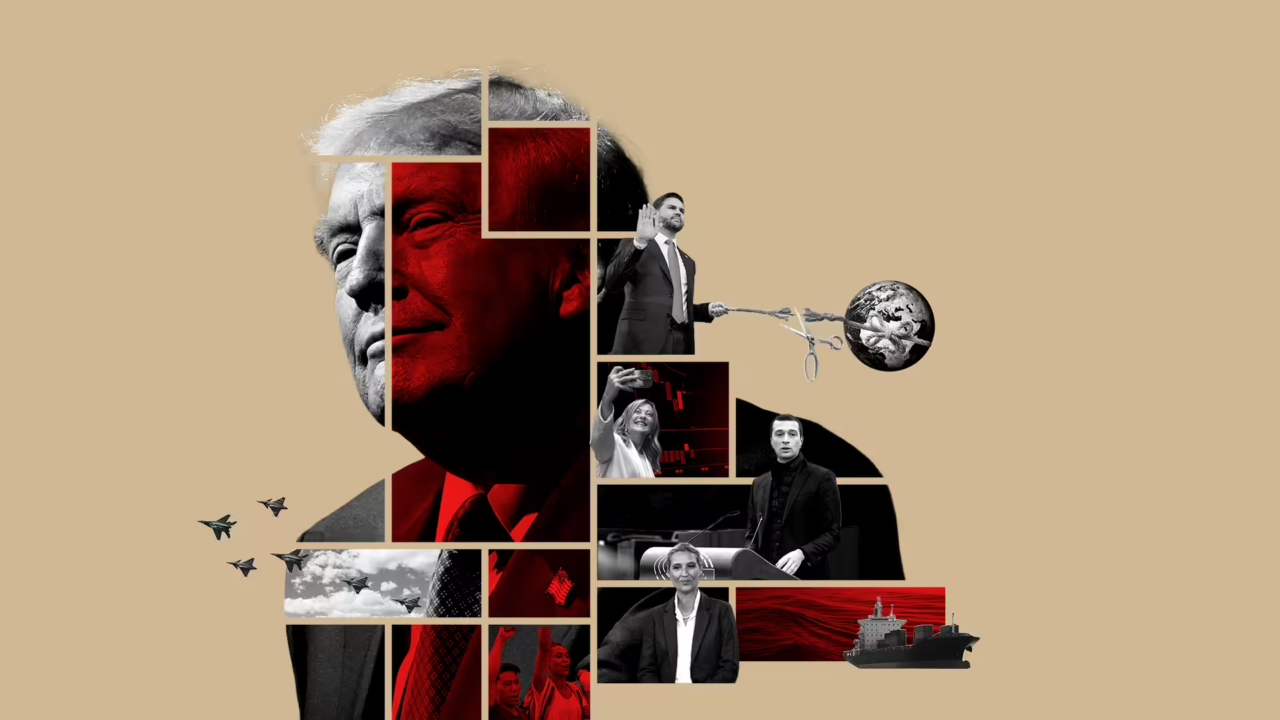

The new right: Anatomy of a global political revolution

Summary

- Right-wing forces beyond the old mainstream are gaining ground on both sides of the Atlantic. They are transforming the US. In Europe, such parties may now even be the largest party family.

- Some dismiss them as mere nostalgists; resentment-merchants peddling a better yesterday. In fact, conversations with the thinkers and politicians of this movement reveal them to be strikingly modern—even post-modern—and well-suited to current times. They truly are the “new” right.

- In much of the north-Atlantic world, this new right wields a forceful analysis of the moment, has built a new class coalition, is driving a policy agenda unified by a focus on national culture and is using new digital communication systems with a deftness the old mainstream lacks.

- Containing and ultimately defeating the new right will take a rival and equally ambitious counter-project. The first step towards creating that is to understand the new right’s own ideas and rise.

Zeitenwende

“[Europe’s] economic decline is eclipsed by the real and more stark prospect of civilizational erasure”, proclaimed the United States’ new National Security Strategy (NSS), published on December 4th 2025. “Should present trends continue, the continent will be unrecognisable in 20 years or less,” the document added. “As such, it is far from obvious whether certain European countries will have economies and militaries strong enough to remain reliable allies”.

It was quite unlike any past NSS—even the one published by Donald Trump’s first administration in 2017. Gone were the establishment American homilies to shared transatlantic values and interests, and the sanctity of the relationship with European allies. In their place was a brutal assault on the politics and culture of today’s Europe that implied that continued US investment in the continent’s security could be conditional on reversing this “civilisational erasure”. It also asserted that the second Trump administration would embrace “the growing influence of patriotic European parties”—seemingly a reference to the rise of the nationalist forces in much of Europe.

For all the sharp intakes of breath the NSS elicited in conventional European policymaking circles, it should not have come as a surprise. Nine months earlier, JD Vance had stunned the Munich Security Conference with a similar message: “What I worry about is the threat from within [Europe]. If you’re running in fear of your own voters, there is nothing America can do for you.” As if that were not proof enough of a new political era in the making, Trump’s vice-president pointedly met with Alice Weidel of the radical-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) while in Munich—but not Olaf Scholz, then the country’s sitting chancellor.

It all confirms that Donald Trump’s “second American revolution” has well and truly arrived in Europe. Its goal is to upend many core mainstream assumptions about domestic politics, the role of the state and international order. The administration seeks to overturn the liberal consensus of the last eight decades; including faith in open markets and free trade, support for managed immigration as an economic and moral necessity, and the commitment to progress (economic or social) as an end in itself.[1] In its place, Trump and Vance are pushing a “national conservative” revolution both at home and in Europe.

In doing so, they are working with the grain of long-term developments within Europe itself. Over the past 15 years parties that oppose the liberal consensus have gained support across much of the continent. Analysis by The Economist shows that hard-right parties now constitute the most popular political family in Europe, as of February 2025 winning on average 24% of the vote in elections; more than either traditional conservatives or social democrats. At the time of writing, parties outside the conventional mainstream lead the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy and Slovakia, and top polls in France, Germany and the UK. They are making their power felt both by blocking common European action and influencing the weakened mainstream.

These politicians and the thinkers around them are ambitious. They talk in terms of remaking the global consensus on a scale comparable to the transformations spearheaded by John Maynard Keynes and Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s and 1940s, and those led by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s.[2] I have spent the past year talking to leading new-right figures in Austria, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Poland, Switzerland, the UK and the US in an effort to understand their movement better—not least in the hope of identifying some ways it can be countered.

The new right is often dismissed as old-fashioned; a backward-looking movement trying to create a better yesterday. But over the course of my research, I have found it to be a hyper-modern, even post-modern, force that is highly adapted to the political, social and intellectual conditions of the 2020s. Therein lies its potency—and the justification for its designation as “new”. Its standard-bearers and theoreticians have a compelling analysis of the moment, a pathway to create a sustainable electoral base, an assertive policy agenda, and organising and communication methods that enable them to thrive in the digital age. These are the four building blocks of this new right, which in many places has integrated them into a coherent and effective whole.

In this essay, I will look at each in turn. I will start by showing how the new right uses the crises of interdependence and the eroded legitimacy of ruling elites as an entry point into politics. Then I will explore the development of a new social base, composed primarily of working-class voters. Third, I will unpack the new right’s policy agenda. And I will end by exploring its communication and mobilisation strategy. This essay uses off-the-record interviews and analyses of new-right literature and programmes to reveal the contours of each one of those pillars, before offering some personal reflections on how mainstream politics should respond.

It is worth noting that there are big differences among the various manifestations of the new right across the West. Some of this has to do with electoral systems, which generate completely different national dynamics. America and France’s presidential systems, Dutch proportional representation and the UK’s first-past-the post model are populated by different sorts of parties with varied electoral incentives.

Then there are disparities produced by history, geography and political culture. Mainstream sensitivities towards the far-right are obviously much greater in a country like Germany, with its institutionalised “memory culture“, than elsewhere. Some of the parties also make for difficult bedfellows. For example, France’s National Rally (RN) has cut ties with Germany’s more overtly hardline AfD over revisionist attitudes towards the Nazi regime within the party. Most recently, Trump’s newly aggressive designs on Greenland have driven a wedge between the administration and the European new right, with leaders like Weidel, Nigel Farage of Reform UK and Jordan Bardella, the RN’s president, voicing their disagreement.

Nonetheless, as this essay will show, there is significant family resemblance between these different movements. They look to each other for inspiration and they all broadly conform to the four-pillar formula I have described. Most importantly, they share a common enemy: liberalism.

1. Analysing the moment: liberalism’s failings and crisis entrepreneurship

Just as communists have always seen the internal contradictions of capitalism as central to their political project, the new right views the tensions at the heart of liberalism as its key to power.

Philosophers such as Alain de Benoist, Patrick Deneen[3] and Yoram Hazony have given voice to a broad conviction on the new right that liberalism, particularly in its post-second world war internationalist iteration, created a global order that is hollowing out our societies. They argue that, following the war, there emerged a powerful consensus across the democratic world: preventing another such catastrophe would mean reconstructing societies along lines that later (during the cold war) came to be known as “liberal democracy”. This ideology has three main principles. First, that all humans are born free and equal in nature. Second, that political obligation can only come from consent. And third, that the primary goal of political institutions should be to preserve individual liberty. The upshot of this, new-right thinkers insist, has been to usher in a politics of individualistic liberalisation at home and globalisation internationally.

Since 1945, this agenda has come to be shared across the mainstream political spectrum from right to left: from the Conservative Party to the Labour Party in the UK; from the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) to the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in Germany; from The Republicans (LR) (and its predecessor Gaullist parties) to the Socialist Party (PS) in France. And after the cold war ended, many concluded that liberal democracy was the final ideology of humankind.

Hazony, an Israeli political scientist, argues that this focus on individual freedom ultimately leads to an atomisation of society, because it ignores critical forms of collective identity which have little or no place within a liberal framework: family, tribe and nation. And although well-intentioned and initially successful, he continues, these principles have gradually eroded the differences between countries, removed the protections for “national cultures” and emptied our societies of meaning. All the while, liberalism became so hegemonic that it was all but impossible to even conceive of genuine political alternatives outside of a liberal framework.

The core critique of the new right is that the deep interdependence of the world that liberalism created has left people powerless in the face of the new crises of globalisation. In his 2023 book, “Konvergenz der Krisen” (Convergence of the Crises), the AfD intellectual Benedikt Kaiser argues that these crises provide the opening for new political forces to capture the political agenda.[4]

Since 2007, when the global financial crisis broke out, crisis has been the order of the day in Europe. This was followed in 2010 by the eurozone crisis; in 2015 war in the Middle East triggered a “migration crisis”; and in 2020 the covid-19 pandemic swept the world. Then in 2022 the immediate security crisis of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine morphed into energy and supply-chain crises in the rest of Europe, which in turn developed into crises of inflation and living costs. Most of these crises live on in one form or another, impacting Europe’s present and future. The possibility of “permanent crisis” comes, in Kaiser’s telling, from the interconnections between all social phenomena in a globalised society where capital flows freely. Citing Antonio Gramsci, he argues that it is only through such an all-consuming crisis of authority that the ruling elite will lose its grip on the social consensus.[5]

Kaiser is 37 and works in the Bundestag for Robert Teske, an AfD MP from the eastern state of Thuringia; the culmination of a journey from the neo-Nazi fringes to electoral politics and a job working for Germany’s largest opposition party. He started out in the “autonomist nationalists”. Photos from that time show him at marches with banners proclaiming “democracy has no future” and decrying the allied bombing of Germany as a “bomb holocaust”. Now Kaiser is one of the most prominent voices of the new intellectual movement around the AfD and is closely associated with the Jungeuropa publishing house, which specialises in bringing anti-liberal texts to German readers. A bookish sort of radical, he professes his admiration for Alain de Benoist and owns no fewer than 42 volumes of Lenin’s writings.[6]

One does not have to share Kaiser’s world view to see how the “convergence of crises” has created opportunities for the new right. Those crises have imposed wave after wave of pressure on the emergent fractures within the liberal consensus (as identified by Hazony). ECFR polling published in 2024 showed how each crisis has served to delegitimise the existing political order on two levels. First, each one overwhelmed the state’s ability to show that it was in control. Second, the policy responses adopted by governments raised crucial questions about whom the state serves, and often suggested that the answer was not ordinary working people.

For example, during the financial crisis, governments rescued the banks but cut welfare payments and let people’s houses be repossessed. On the climate crisis, they raised heating costs for households but allowed oil companies to keep growing. Migration helped corporations turn incredible profits but has driven down wages, driven up house prices, put pressure on public services and changed the character of more vulnerable communities. In Ukraine, Western governments have rallied to help a foreign country in need, but at the cost of an inflation crisis due to rising energy bills and of defence spending hikes funded by higher taxes or cuts elsewhere. During the covid-19 pandemic, many white-collar employees could work from home while blue-collar and low-wage service workers had to risk their lives on the front line.

The cumulative effect of Europe’s wave of crises has been to create a durable set of new political identities. ECFR data appears to support Kaiser’s intuition that the rapid succession, and sometimes simultaneity, of the crises has not brought society together but has instead separated it. Different people experience different crises with different intensities, with some identifying most with the dramas of the migration crisis while others are more focused on climate change. And so each of these five issues ends up with its own sizeable constituency of voters who cite it as the one that most preoccupies them (see chart below). These constituencies are unevenly distributed between different generations and between different countries. At a time when the left-right divide is breaking down, the crisis tribes are a good way to explain politics in this new age.

The new right has exploited this “polycrisis” context in notable ways that help it stand out from mainstream forces.

Incumbent governments promise—and often fail—to restore stability and order, but are constrained by institutions and slow processes. The new right, on the other hand, has argued that breaking through those constraints is the only way to deliver change in a hidebound system. At the 2025 National Conservatism (NatCon) conference, an annual gathering of the international new right, one participant put it to me bluntly: “smashing things is the point”.

Trump’s first year in office has been the perfect illustration of this. As president he has ignored norms, procedures and often laws in his attempts to close the US border, fire government officials, shut down federal agencies, defund National Public Radio (NPR) and Planned Parenthood, and bring the military to heel. Recently he did so in dramatic style by ordering the capture of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s president, and even flirting with seizing Greenland from Denmark. Many have objected to these steps, with good reason. But politically they give Trump his distinctive edge, portraying him as a leader doing something where mainstream politicians wring their hands. The same mechanism is at work in Europe when, for example, the RN’s Marine Le Pen speaks of disregarding European law to prioritise French citizens’ access to housing, jobs and benefits; unilaterally cutting France’s contributions to the EU budget; and even disapplying the primacy of European law altogether.

An era of crises also enabled such parties to exploit their nimbleness, repositioning and recasting themselves in response to events while mainstream parties prove more cumbersome. Thus “crisis entrepreneurs”, both on the radical left and the right, have emerged to challenge liberalism from whichever angle best suits the moment. They complain one minute about the euro crisis, the next about migration, then about vaccines, and then the response to climate change.

Maybe the best example of this is the AfD. It originated during the eurocrisis as a single-issue party opposed to bailouts and Germany’s membership of the eurozone, but took advantage of the 2015 migration crisis to reinvent itself as the country’s principal anti-establishment force. It subsequently harnessed anger at covid-19 lockdowns and then at rising costs in the wake of the Ukraine war. But almost all of these new right parties—from Farage’s Reform UK, to the RN in France, to Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy (FdI)—have used similarly light-footed tactics.

2. The new class war

However, the new right’s crisis-era tactics would not work if it did not also have a reliable social base; a solid electoral bridgehead from which to build out. This is where its new class coalition, the second of the four pillars of its formidable rise, becomes relevant.

That bridgehead has been the communities that feel they are on the wrong side of liberal interdependence and globalisation—and that feel ignored by governments’ attempts to confront the manifold crises. It amounts to a new class coalition gathered around socially conservative but (purportedly) economically more progressive positions. Referring to these crises, Kaiser has argued that: “The left has abandoned the social question in favour of minority politics. Let’s make it our heartfelt cause—it’s capitalism that requires constant migration, but people do not want it. The welfare state is there for its own people, not as a pull factor for multicultural elements.”[7]

Maybe the key issue which differentiates the new right from the old right is its economic policies and views on class. As a young French RN politician recently told me: “Our initial struggle was with the ‘syndicate of the old right’, which was pro-globalisation, pro-EU and aligned with the neoliberal agenda. Their class base was the droite de petite bourgeoisie—which had become blinded to the growing impoverishment of the [working] classes”.[8]

Likewise, a leading member of Confederation, a far-right Polish outfit founded only in 2018 and now enjoying consistently double-digit poll numbers, told me that his party has tapped into a widespread feeling that the government was doing nothing to protect its citizens and the economy.[9] Voters, he continued, are aggrieved that China, the EU, and the big German companies that snapped up the best Polish property and companies, are deindustrialising parts of the country.

At NatCon 2025 in Washington, speakers launched many more attacks against the traditional Republican establishment than against Democrats. Many of the speakers explicitly rejected Reaganite fusionism and Bush-era globalism. The establishment right was no longer treated as a misguided ally but as an enemy class. For example, Rachel Bovard from the Conservative Partnership Institute declared “polite Republicanism” dead and attacked compassionate conservatism, classical liberalism and constitutional conservatism as “surrender tactics”.

Also at NatCon, Jamieson Greer, Trump’s trade representative, argued that free-trade policies were not a natural endpoint in economic theory, but a late-20th-century deviation imposed by globalists and corporate interests. Senator Eric Schmitt from Missouri mocked the narrative of “America as an idea”, arguing that America is instead “a place and a people”. One of JD Vance’s advisers told me that their mission is to abandon the old idea of “country-club republicanism” and to replace it with a new variant of “working-class republicanism” in places “blown out by globalisation” and tired of being bossed around by lawyers, regulators and self-serving bureaucrats.[10]

In part, this is about portraying the conventional Republicans and Democrats as the voices of Wall Street and Hollywood, of lawyers and regulators, of a “woke” deep state opposed to the interests of ordinary Americans. But it also has policy substance (of which more in section three). Strategists in MAGA-land such as the Vance adviser, as well as researchers at the Heritage Foundation and the conservative economist Oren Cass with his American Compass think-tank, have promoted a “worker-centric conservatism” that is critical of capitalism as represented by corporate America. Cass has even called for Republicans to shed their “free-market orthodoxy”.

This vision of a working-class bloc pivoting from mainstream conservatism and the left towards the new right is more than a pipe dream. It is becoming electoral reality in much of the West.

For example, in the US, Trump won the 2024 election in large part because he managed to forge a new working-class coalition, winning 66% of white voters without a college degree, compared with a paltry 32% for Harris. Support for Trump was lower among non-white voters, but nonetheless 47% of working-class Latinos and 56% of working-class voters of all races backed him—remarkable figures for a GOP candidate.

Likewise, for most of Britain’s post-war history, the main dividing line was between working-class support for Labour and middle-class support for the Conservatives. This has now come undone. Boris Johnson led the Tories to victory in 2019 by convincing working-class voters in traditionally Labour seats in northern England to “get Brexit done” by voting for him (winning 41% of working-class voters in the process, a share unthinkable in the British politics of yore). These days, according to the pollster YouGov, “half of Labour voters who are abandoning Labour for Reform UK are working-class”. Indeed, as the political scientist John Curtice has argued, one of the hard rules of British politics used to be that class was the best predictor for whether voters supported the Labour or the Conservative party. But today, class has lost its old relevance. In fact, the only party for which class (or rather, educational background) is a predictor of voting behaviour is Reform, as it is now the dominant party for people without university degrees.

In Germany, working-class support for the social democrats is down from 48% in 1998 to 12% in 2025. Meanwhile, the AfD won 38% of working-class votes in the 2025 election (up 17 points on 2021) compared with 21% in the overall electorate. This from an outfit once referred to as the “professors’ party” for its upper-middle class roots among conservative intellectuals.

In France, the contrast is even starker. In the first round of the 2024 snap parliamentary election, Le Pen’s RN secured 59% of the working-class vote, while the PS, LR and Emmanuel Macron’s centrists combined only scraped together 41% (compared with 43% for Le Pen at the 2017 presidential election and 55% for the other groups).

Of course, the irony of ultra-privileged individuals like billionaire nepo-baby Trump, former City of London trader Farage and the AfD’s co-leader Weidel, a former Goldman Sachs banker, posing as tribunes of the people is lost on nobody. Those in the political centre will rightfully question the new right’s policy bona fides, particularly given Trump’s tax cuts for the ultra-wealthy while he pursues social spending cuts in his Big Beautiful Bill. They will ask about the substance of the new right’s working-class economic agenda. Does it seek to strengthen unions and introduce minimum-wage legislation? Shift the tax burden away from low earners? Strengthen working people’s rights as workers and consumers?

Such questions are fully justified. And it is unclear whether individual new-right parties currently in opposition will pursue any of these policies if they come to power—not least as they are often made up of diverse coalitions stretching from long-standing critics of free markets like Cass to libertarians like Elon Musk. But what the new right has understood is that the public square is not the same thing as an economics seminar room. Symbolic policies like building a wall, introducing tariffs or committing to put wrong’uns in prison can do more to communicate whose side a party is on than more substantive policies.

In any case, to talk with many on the new right—from the RN politician quoted earlier to Kaiser’s colleagues in the AfD—is to grasp that they see their new working-class supporters as merely an initial bridgehead. From there they are seeking to widen their class base by moving beyond a simple “elites v people” dichotomy towards a truly majoritarian argument which can count on more than 51% of the population for support.

Different parties are still at different stages of this process, although the RN may be among the most advanced. The party’s focus has already moved from elite-bashing and metropole-periphery divides to big-city insecurity and what the party claims are its demographic drivers.[11] That is consistent with its growing ambitions as it looks beyond its neglected rural and post-industrial heartlands to the urban and suburban areas that decide elections.

A recently leaked AfD strategy paper outlines a similar course: to make the party salonfähig (acceptable in polite society) by fanning polarisation between the far-left and the centrist bourgeois elements of society, with the eventual goal of replacing the CDU as the country’s natural governing party. Indeed, some recent opinion polls shows that 51% of Germans would consider voting for the party. What remains unclear is whether the AfD will choose to pursue a “Meloni model” of winning over the old right or a “Kickl model” of replacing it—a distinction Kaiser makes.

Seen in this light, the new right’s overtures to working-class voters are not class war for its own sake but a stepping stone to a genuinely majoritarian coalition of support enabling it to enact its sweeping policy agenda.

3. The policy agenda: immigration, trade, foreign policy and the state

That process—winning over working-class voters who feel that they are losing their status in society by pushing back against globalisation—is directly expressed in the new right’s policy agenda. It has four main elements: immigration, trade, foreign policy and the reinvention of the state. But more than electoral calculations, they are a joined-up ideological project of transformation organised around the central goal of “restoring” a traditionalist version of national culture to the heart of civic life. This is not culture as one topic among many, but as the overriding priority cutting through them all.

In section one, this essay explored how the intellectuals of the new right have bemoaned the collapse of collective identity in Western societies. For Hazony, the consequence is that politics is now split between, on the one side, a “neo-Marxist wokery” that promotes new identities based on gender, race and sexuality; and, on the other side, national conservatism with its focus on family, tribe and nation.

To counteract the allegedly centrifugal forces of liberalism and wokeness, the new right has specifically focused on policies designed to rebuild a nationalist cultural identity centred on its conservative interpretation of Judeo-Christian values. This politics of “national preference” encompasses all four of those elements: borders, economics, foreign policy and the state. Each seems to reflect prevailing concerns among both the new right’s working-class base and—as rising poll numbers suggest—growing numbers of swing voters in the political middle.

Borders and migration

The project begins with national borders. Immigration is perhaps the new right’s single biggest issue, partly because it combines economic with cultural motives. In Europe, it is one topic where all the parties of the new right agree, and an issue of totemic symbolic importance; the one that Hungary’s Viktor Orban made his own in the migration crisis of 2015 and which powered the Brexit campaign in the UK.

The fundamental new-right argument goes as follows. Liberal claims that open immigration (just like free trade and the free movement of ideas) would benefit everyone was a betrayal, enabling elites to focus exclusively on maximising profits at the expense of good economic conditions for everyday voters, the security of streets and—above all—the preservation of national culture.

This latter point’s importance can hardly be overstated. Orban talks about how European countries are committing “civilisational suicide” by inviting diverse immigrants in. Vance famously argued that: “America is not just an idea. It a group of people with a shared history and a common future”. The new right’s answer, therefore, is to do whatever seems necessary to stop new arrivals from coming and to send back many of those already present.

One of the biggest stars of NatCon 2025 was Trump’s border tsar Tom Homan, who spoke proudly of his background as a border patrol agent and his love for his new job: “I wake up every day like a kid in a candy shop”. He claimed that he had managed to reduce irregular migration by 96% in just seven weeks (a figure not independently verified). He further boasted that ICE would deport 400,000 illegal migrants by the end of the year and that he was in the process of recruiting another 10,000 Immigrations and Customs officials.

Meanwhile in Europe, an RN politician explained to me his party’s three-pronged strategy. At the national level the task was returning powers to the state and making it more difficult for irregular migrants to move from one member state to another. At the European level it was strengthening Frontex and reinforcing the external EU border. And at the global level it was externalising border controls and making as many returns deals with third countries as possible.[12]

This hyper-restrictive agenda on migration is closely connected with the new right’s vision for the family. As Victor Orban’s political director, Balazs Orban (no relation) put it to me: “The purpose of these policies is always the preservation of the nation as a community”. He says that demography and family policy are the most important areas. That both means restricting immigration and introducing “positive discrimination” and financial support to heterosexual couples with children. The idea, he continued, is to introduce a “family tax revolution” where a mother with two children will not pay any income tax in her entire life. Likewise, Hazony spoke of reasserting the distinction between man and woman, whose abandonment he claimed “is just something that even the great liberals of 100 years ago… none of them would have thought was a sensible thing to move towards”.

A final part of the national-conservative critique of liberalism is that liberals’ unconditional embrace of progress has left people with nothing to hold on to. One speaker at NatCon used the umbrella term “LGBTQ+” as a metaphor for this, arguing that identity has become so fluid that new sectional identities are constantly being invented—with the “+” symbolising that the process lacks a clear endpoint.

Trade and economics

If walls are the new right’s answer to migration, then tariffs are at the heart of its economic strategy. It views economic nationalism, and the ultimate goal of reindustrialisation, not just as a political but fundamentally a cultural and even moral priority. At NatCon, for example, Trump’s trade tsar Greer complained that free trade had gutted America and that Bush’s hubris in invading Iraq was only matched by his hubris on free trade with China. He complained that the US had abolished its borders and outsourced sovereign trade decisions to the WTO in Switzerland.

Trump’s goal is first to re-establish economic sovereignty through tariffs and then build an autonomous trade policy that will bring production back to America. This will involve pursuing autonomy on rare earths and other minerals and creating a production economy for whole chains of industrial products that are currently imported. RepresentativeRiley Moore from West Virginia argued at NatCon that industrial capacity drives national strength: “The same voices that called for foreign adventurism also hollowed out our heartland and sent our manufacturing jobs overseas. We now face a new choice: rebuild or be left to the ashes of history. We cannot deter our adversaries if we cannot out-build them”.

In Europe, many parties on the new right have also railed against free trade and globalisation, especially since many are rooted in agricultural and declining industrial areas that view such integration more sceptically than most.

In France, Le Pen has decried the EU’s trade agreement with Mercosur as an attack on “the survival of our agriculture and therefore the sovereignty of our country”. The RN has attacked the pact as a threat to farmers. In Poland, Law and Justice (PiS) has taken a similar line, warning that the deal could undercut the domestic agriculture industry; Confederation has warned on social media that the agreement is “terrible news for Polish farms”. Under that pressure, both the Macron and Tusk governments opposed the pact in the European Council.

On economic matters too, then, the centrality of national culture is clear. New-right parties are advocating protections for deep-rooted agricultural or industrial interests—not just on economic grounds, but on grounds of national identity and pride.

Foreign policy

This cultural rationale also informs new-right foreign policy, the third of the four main elements of its overall agenda. These start from the premise that the liberal international ideals of the post-cold war order are at odds with national autonomy and identity.

In my conversation with Vance’s adviser, he compared the US today to Britain after the second world war and framed Trump as an American Attlee to Biden’s Churchill.[13] The choice at the last presidential election, he argued, had been between maintaining the trappings of global empire or tending the American homestead. These arguments also made up page one of the Trump administration’s NSS: “Our elites badly miscalculated America’s willingness to shoulder forever global burdens to which the American people saw no connection to the national interest”. Such policies, it went on to insist, “undermined the character of our nation upon which its power, wealth and decency were built”.

In Europe, too, new-right foreign policies come down to the character of the nation. Here this most fundamentally takes the form of opposing European integration perceived as adverse to national particularism. Le Pen captured this perspective in a 2019 speech. Citing Joan of Arc, Paul Verlaine and Charles de Gaulle, and comparing the EU to “an ogre who burns to devour the beautiful sleeping princess”, she argued: “This aspiration for physical, social, democratic, linguistic and cultural protection is expressed all over the world: in the United States, India, Russia, China, Great Britain, Italy and in many other countries. This is the shift that is about to happen throughout Europe”. Such a shift, she said, would be about respecting national differences within a wider Western civilisation: “Our Europe is not sixty years old, but is thousands of years old. […] It is not from Brussels or Berlin, but from Athens and Rome. It draws its roots from a Judeo-Christian heritage and holds freedom as its cardinal value”.

This thinking permeates the new right today. My RN interlocutor echoed it in our recent conversation: Europe as a common civilisational project made up of independent nations.[14] It is echoed, too, in the distinction new-right thinkers draw between Europe and the EU. As James Orr, a Cambridge professor close to Farage and Vance, recently told a German journalist: “I love football, but I hate FIFA, because I love football; I love Europe, which is why I hate the EU”. For Orr, the RN politicians and Vance (who, like Orban, has warned of Europe’s “civilisational suicide”), the broader goal is a series of concentric circles: civilisation, nation, tribe, family. That is the foundation of their foreign policies.

In practice, this means an emphasis on national autonomy and protection—and an instinctively positive demeanour towards nationalists elsewhere—combined with a certain openness to common European policies in pursuit of those goals. The sense of a shared European or Western civilisation, combined with the deterrent debacle of Brexit, means new right parties today tend to seek not to leave the EU but to change it from the inside. As Balazs Orban put it to me: “We are trying to strengthen our presence [in Brussels] in every way. It’s part of our strategy. [The EU] can be changed and we want to change it. We now know how it works; we are getting stronger and [the mainstream forces] are getting weaker”.

A common criticism among new-right parties is that European cooperation in its current form is not delivering on its promise: that policies purporting to make interaction within Europe easier and shield Europeans from external threats (migration, industrial competition, supply-chain disruption) are doing the opposite. When it comes to geopolitical threats, however, they are more divided. A recent ECFR study found them to be generally more open to cooperation with the nationalist regimes in Moscow and Beijing than most European mainstream parties.

But there were some notable exceptions. PiS shares the prevailing Polish wariness towards Moscow. Spain’s Vox is hawkish on China. And Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 forced even instinctively pro-Putin new-right parties to rein in their old impulses. The RN repaid a politically awkward Russian loan in 2023. In Britain, Farage and his Reform party have heavily qualified his past expressions of admiration for Putin. Others, however, like Hungary’s Orban and Slovakia’s Robert Fico, have made no secret of their pro-Moscow and anti-Kyiv positions, which are often framed in terms of European living standards and energy security.

One of the most interesting developments on foreign policy relates to the new right’s conflicted attitudes towards Israel. As some far-right parties seek to detoxify themselves and their association with Nazism, they have made it a point to embrace Binyamin Netanyahu’s right-wing government and his prosecution of the war in Gaza (in particular, they share a common hostility to Muslims).

In the US, however, Israel has emerged as an unlikely source of division within the new right. Although many of the movement’s leading lights continue to hold strong pro-Israel positions, two groups are moving away from that consensus. On the one hand are the foreign policy restrainers who worry that American support for Israel risks dragging the US into wars a long way from home. On the other is a growing cohort of younger right-wingers who have embraced the hallucinatory antisemitism of the Hitler-venerating Nick Fuentes and his “groyper” movement. Rod Dreher, a conservative writer, has described with concern a recent trip to Washington, where he estimated that between 30% and 40% of Republican staffers under the age of 30 are groypers.

When it comes to the transatlantic relationship, these parties’ opposition to the post-cold war liberal consensus has conventionally seen them oppose Atlanticist foreign policies and participation in bodies like NATO. But the second Trump administration—well-disposed to their ambitions, as the NSS confirmed, and aligned with their civilisational perspective—has scrambled the politics of Europe-US relations.

ECFR polling published in January 2026 found that although America’s standing as an ally has suffered across the world, it has fallen especially in Europe, which Trump has heavily alienated. Only 16% of EU citizens still consider the US an ally.In some EU member states, nearly 30% of the public (including in France, Germany and Spain) now view the US as a rival or an enemy, a number which reaches 39% in Switzerland. Among the Europeans now most positive about the US political system and its sitting president are supporters of new-right parties like FdI, Orban’s Fidesz, PiS and Vox.

This recast Atlanticism also showcases one of the other striking features of new-right foreign policy: its high degree of international and intellectual connectivity, notwithstanding the disparities mentioned in the introduction to this essay. Conferences like NatCon and the Conservative Political Action Conference are one attempt at bringing likeminded strategists of the movement together. Hungary, in particular, has become a nexus of such efforts, with influential American intellectuals like Dreher and Gladden Pappin setting up shop at state-affiliated think-tanks and universities in Budapest.

In Gladden’s words: “It’s truer today than it was 20 or 25 years ago that conservative parties on both sides of the Atlantic feel that they are both talking about the same thing… It’s natural that there will be more exchange”. This process is taking place on many levels and between many different countries. Kaiser, for example, has translated the work of French right-wing authors like Jean Raspail and Pierre Drieu la Rochelle into German. Over time, the result of this cross-pollination could be a markedly different type of transatlantic relationship to the one of recent decades.

The state

The final policy element of the new-right agenda is recasting the national state. One of the darlings of the MAGA movement isRussell Vought who—as head of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)—is Trump’s tsar for reshaping the state. He portrays bureaucracy as the single greatest obstacle to a nationalist government, because in his view it rejects the very notion of a national culture. He traces the “administrative state’s” origins to Progressive-era reforms, post-Watergate rules, and describes it as now “woke and weaponised”. Dismantling it, therefore, is not just a tactic for short-term victories but a strategic project aimed at reshaping institutions to safeguard America as a white, Judeo-Christian culture.

These ideas are now finding purchase across the Atlantic. In a recent blog post titled “Restoring Government”, Danny Kruger, an MP for Reform UK, referred to the civil service as “an apparatus of the establishment” and officially “put [it] on notice”, promising to cut staff numbers drastically. In France, RN politician Fabrice Leggeri similarly warned civil servants that “people [in the civil service] who aren’t happy [with the RN in power] need to know that they can leave,” adding that “those who support “the Trotskyists” and don’t want to work for [Bardella] can “go back to help the Trotskyists to prepare their programme”.

What unites such bids to cut and rebuild the state is an underlying motivation to align it with the (supposed) protection of national culture. Dreher, part of the transatlantic Budapest set, put it to me that liberal intellectuals’ thought on the state has long sidelined culture as a topic of relevance. But now, he said, that cultural dimension has come “roaring back” with the growth of the new right.

4. Communications: a fragmenting public sphere and the battle for “free speech”

The biggest opportunity for the new right has been the fragmentation of the public sphere—and, relatedly, the disempowerment of the gatekeepers of the mainstream media. The rise of new digital platforms, especially social media, has offered its politicians and commentators new ways of shaping popular narratives. That constitutes the fourth pillar of its politics.

Once the information ecosystem begins to splinter, politics becomes a battle over who controls meaning itself. Echoing the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, Dreher has argued that the present moment is one of “liquid modernity”, in which events are accelerating so fast that institutions and practices do not have the time to stabilise before they shift again. In such a world, people cease to believe that there is a such thing as absolute, knowable truth, and instead begin to rely on their emotions or their individual subjectivity to determine what they accept to be true.

Liberalism rests on the assumption that there are such things as objective facts and subjective opinions, that truth can be approached through scientific method, and that politics should take place in a shared public sphere in which ideas are debated rationally. But the new-right politics begins by questioning the power of conventional elites to define what is right, what is wrong and what matters. It is not just about holding different opinions anymore; it is about holding different facts.

Dreher cites the case of Isabel Vaughan-Spruce.[15] A Christian activist who was arrested twice in Birmingham for praying outside an abortion clinic, she has become a cult figure in the MAGA information sphere. And yet, Dreher alleges, the mainstream media had never even heard of her. Another example of this disconnect between establishment and social-media concern is Musk’s recent amplification of stories about child-grooming gangs in Britain, actively reshaping what counts as important news.

The American commentator Chris Hayes has argued in his recent book, The Siren’s Call, that the information age has given way to an “attention age” in which attention itself is commodified and extracted at scale as a finite resource.[16] He draws an analogy with what happened to labour in the industrial revolution. In the pre-industrial age, he claims, work was highly specialised and could not be easily substituted. But with mechanised production, it became completely fungible and commodified. That is now happening to our attention, which is being turned into units that can be traded.

In this environment, political actors face intense pressure to capture eyes and ears amid endless digital distractions. In an environment where content that triggers strong emotional reactions (whether outrage, fear, or tribal loyalty) is rewarded with greater reach, the new right often outpaces mainstream parties in the digital competition for voters’ attention. Issues like climate change or transgender debates are no longer scientific issues, but have instead become markers of identity, politicised along tribal lines.

Thus, the media that once underpinned liberalism is now giving way to a new information space that is powering its challengers. Nigel Farage once told me in an interview, “I wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for the internet”.[17]The same is true of many new-right politicians. A leading member of Poland’s Confederation told me that the new media had been key to his party’s electoral success. “We had been censored from mainstream media because of PiS’s control over public broadcasting”, he said, “and had to spend a lot of time on social media looking for alternative platforms”.

An analysis of the social media accounts of members of the European Parliament (MEPs) recently conducted by Politico found that while only about one-quarter of those accounts belongs to far-right or right-wing groups, those MEPs’ accounts accounted for a majority of total TikTok engagement (nearly 39 million likes and 2 million followers), dwarfing the presence of the larger, more moderate party blocs. By contrast, all of the MEPs from the centre-right European People’s Party, the largest group in the parliament, together were responsible for just under 3% of all likes in the sample.

A central part of the new-right agenda is to deepen its hold on this new information space. Vance is obsessed with a particular definition of “free speech” as a meta-goal for the Trump administration. His speech to the MSC and other interventions have framed this as a matter of national character: “I happen to think your democracies are substantially less brittle than many people apparently fear”. (“Brave European leaders have been saying this for a long time”, added Meloni approvingly in her reaction to the speech).

At NatCon 2025, various speakers claimed that the ancien régime had used censorship as its main survival mechanism. Republicans in Congress have set up a committee to investigate what they call the “censorship industrial complex”, supposedly cooked up by the Biden administration in cahoots with European governments and the European Commission. Indeed, much new-right energy is directed at rolling back the commission’s attempts to regulate social media. Kristen Waggoner from the Alliance Defending Freedom told the NatCon crowd that the EU’s Digital Market Act and Digital Service Acts constituted “the most corrosive censorship regime in the world”. The close ties between MAGA-land and American digital media giants only serve to intensify the movement’s commitment to roll back these checks on Silicon Valley’s power.

But the new right’s communication dominance is about more than mastering new platforms. It reflects an entirely different style of politics, one more focused on identity and emotion than statistics and facts. Part of the new right’s genius has been to lean into the showbiz and meme-able elements of political performance and spectacle.

This essay has already taken in some of the inherent contradictions and logical holes in the new right’s project. But it would be wrong for liberals to believe that picking holes in its agenda will get them very far. The new right understands that in this new media age, “deliverism” and evidence are merely part of the equation, and often matter much less than emotional resonance or demonstrating a shared identity. This is why thinkers like Hazony frame modern politics as a three-way struggle between liberalism (which is all about individual identity), wokeism (which is all about minority identities) and national conservatism as the only movement to offer voters a majoritarian identity. Without a persuasive rival language of identity, mainstream politics will struggle.

How mainstream politics can adapt

My conversations with some of the new right’s leading thinkers, strategists and politicians have convinced me that it is a political force distinctly adapted to today’s world. They have a compelling narrative about our crisis-driven times; a project to build a social base for their agenda; an assertive policy programme; and a strategy to use their primacy in the information space to win power. Meanwhile, mainstream parties in most places are struggling to adapt.

Without properly understanding new-right parties’ ideas and ways of organising themselves, it is hard to understand their appeal and predict what they will do next. Often, mainstream parties go through a cycle of first denying that the new right is a threat, then copying it in the hope of defeating it, then reverting to denial. But history shows that profound change in the political weather requires adaptation, and that this adaptation is only possible once one fundamentally understands that change.

In Britain, for example, neither Margaret Thatcher’s fellow Conservatives nor the Labour Party initially took her seriously as an ideological challenge. So it fell to, of all outfits, the fringe magazine Marxism Today to explore her politics in proper depth; using Gramsci’s writings to analyse it, in the process coining the term “Thatcherism” and ultimately seeding the counter-movement that resulted in New Labour. Mainstream parties confronted by the new right today face a similar analytical task.

The biggest danger, in this era of unorder, is that centrists appear to be representatives of the status quo. Too frequently they seek to fight the new right merely by styling themselves as grown-ups who understand the mechanics of complicated issues and institutions, and by warning that populists just want to blow things up. This approach fails to acknowledge that in an anti-incumbent, polarised age, many voters see the prospect of disruption as a feature of the new right rather than a bug. As one French farmer told a reporter ahead of his country’s legislative election in 2024: “I voted for Jordan Bardella [because] I wanted to send a message to our current government: it has to change. We are in a country that is going to sink”.

Instead, mainstream politicians should follow three main principles. First, and most fundamentally, they need to stake out political ground on which they have real standing and can communicate frankly, and attack the new right from there. Instead of pretending that unorder can be neatly solved, they should address people’s fears and give them the tools to survive and thrive within it.

Some have realised this sooner than others. Mette Frederiksen in Denmark has found an authentic way into the debate on migration, rooting her policies in her genuine and heartfelt commitment to the Danish welfare state. Andy Beshear, the popular Democratic governor of traditionally Republican Kentucky, has urged his party to “talk to people like normal human beings” and to “share our ‘why’”—in his case his Christian faith. Zohran Mamdani, New York City’s new mayor, has triumphed by mastering the new media. But there are also less well-known examples—like Lawen Redar, a centre-left Swedish MP of Kurdish heritage, who has found a new way to talk about integration and migration.

One useful source of opportunity is Trump’s general toxicity in Europe and the failures of his administration. Harnessing the political force of anti-Trump feelings—as Mark Carney did in Canada’s recent election and as Pedro Sánchez and Anthony Albanese have done in Spain and Australia respectively—could help give new-right parties aligned with the president some of the encumbrances of incumbency. There are parallels with Brexit, which initially emboldened eurosceptic parties but then became a millstone round their necks when the costs of Britain’s withdrawal from the EU became apparent. Polling conducted by ECFR reinforces this message—while also revealing the limits of anti-Trump sentiment. Opposition to the American president is starker in Denmark, the object of the president’s aggressive claims on Greenland, than in other western European states.

Second, mainstream politicians must find a way to govern which does not leave working-class voters behind. For much of the post-cold war period, policymakers treated growing international interdependence as an uncomplicatedly good and universally beneficial trend, overlooking its differential impact on different social groups. As this essay has shown, the new right’s protectionist trade and economic pitch responds to the failings of that course; appealing to voters that feel left behind. Mainstream parties have started to adapt, with a new focus on “levelling up” prosperity to neglected groups or regions. But it will take greater political imagination to build a genuinely convincing new package of economic, welfare, migration and climate policies that accept the reality of interdependence while derisking it in the eyes of vulnerable voters.

Third, they must knit together a new collective identity. If the new right’s organising principle is traditional national culture and the related emphasis on civilisation, tribe and family, the centre needs something at least as appealing and motivating; its own story of belonging and underlying rationale for its policies. This new collective identity will need to take root in the public sphere, including its burgeoning and fast-moving digital spaces. That will require greater digital and emotional literacy from politicians. It may also require a more confrontational approach towards the tech bros, as tribunes and handmaidens of the new right.

Perhaps the most important factor, which will determine the success or failure of these three strategies—disrupting the status quo, derisking for the working class, and finding a new collective identity—is authenticity. Parties must identify those issues where they have sufficient standing to communicate these new strategies in a way that reaches people. But the starting point has to be a real spirit of inquiry towards the new political forces of our times, foremost among them the new right. Approaching them with curiosity for their ideas and respect for their voters, rather than contempt and bemusement, is the first step towards containing and ultimately defeating them.

[1] Deneen, Patrick J. Why Liberalism Failed. Yale University Press, 2018

[2] Conversations with various new-right figures, 2025

[3] Ibid.

[4] Kaiser, Benedikt. Die Konvergenz der Krisen: Theorie und Praxis in Bewegung 2017–2023. Jungeuropa Verlag, 2023

[5] Haug, Wolfgang Fritz. “Hegemony.” Historical‑Critical Dictionary of Marxism: A Selection, edited by Wolfgang Fritz Haug et al., vol. 1, Brill, 2023, p. 340

[6] Conversation with Benedikt Kaiser in Berlin, November 2025

[7] Kaiser, Benedikt. Die Konvergenz der Krisen: Theorie und Praxis in Bewegung 2017–2023. Jungeuropa Verlag, 2023

[8] Conversation with a leading RN politician, Paris, May 2025

[9] Conversation with Confederation politician in Warsaw, September 2025

[10] Conversation with JD Vance adviser, Washington, April 2024

[11] Conversation with RN politician, Paris, May 2025

[12] Ibid.

[13] Conversation with JD Vance adviser, Washington, April 2024

[14] Conversation with RN politician, Paris, May 2025

[15] Conversation with Rod Dreher, London, May 2nd 2024

[16] Hayes, Chris. The Siren’s Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource. Penguin 2025

[17] Conversation with Nigel Farage, London, 2014

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.