How to arm a pacifist: Lessons from Ukraine for the EU’s defence

Summary

- The success of the EU’s rearmament hinges on its leaders learning lessons from Ukraine.

- They will have to direct their efforts towards three problems that strike at the very heart of the union: time (or lack thereof), regulation and relevance.

- Time relates to the urgency with which Europe has to take responsibility for its own defence.

- Regulation involves the EU creatively adapting its rules so it can integrate Europe’s defence industrial ecosystem (and thus accelerate its rearmament).

- Relevance is the imperative not only to prepare for a future war, but for the warfare of the future (and thus be ready to respond quickly whatever the future holds).

- At every step, European leaders will have to ensure voters across the continent know military might is not a luxury—it is a prerequisite for the EU’s model of peace and prosperity.

From software to hardware

Trucks, sheds, off-the-shelf drones. Much of the hardware Ukraine’s intelligence service used in “Operation Spiderweb” was not created for war. It was the ingenuity of people that on June 1st inflicted around $7bn worth of damage on Russia’s fleet of bombers, thousands of kilometres inside its territory. The EU was not created for war either. But as with trucks, sheds and off-the-shelf drones, people can use their ingenuity to adapt the bloc’s hardware to be ready for war if it arrives.

This is far from the only lesson the EU can learn from Ukraine. The planning of Operation Spiderweb took 18 months of a three-year war. In 2025 alone, Russia has terrorised Ukraine with more than 27,000 aerial bombs, over 11,000 Shahed drones, about 9,000 other attack drones and more than 700 missiles. That Ukraine still existed to carry out its audacious asymmetric raid was thanks to the creativity and bravery of its people, but also the air-defence systems, tanks, ammunition and other weapons its allies helped provide. Quantity still matters. Being ready to intercept the drones and missiles matters.

EU leaders have finally realised they too need to be ready. They need to be ready to ensure Ukraine’s continued survival without US support. They need to be ready in case the “grey zone” between peace and war that exists in Europe turns into something else. And they need to be ready for the EU to become a hard power that can shape the global order in a world of disruptive strongmen.

To do this, EU leaders will have to learn from Ukraine’s lessons. This paper argues that the development and implementation of the EU’s rearmament will involve trade-offs that strike at the very heart of the union. Its leaders will have to do nothing less than change their perception of time, regulation and relevance. But, by ingeniously adapting the EU’s hardware, they can integrate the bloc’s defence industrial ecosystem. This will enable Europe to produce more weapons, more quickly and—crucially—more cost-effectively than if the sector remained fragmented. To become a true hard power, however, the EU will have to ensure its political landscape and military might are ready not only for a future war, but for the warfare of the future.

The countdown

The true Zeitenwende, or “turning point”, in Europe’s defence did not take place until February 14th 2025. On that day, US vice-president J.D. Vance gave a speech at the Munich Security Conference which effectively ended things between America and its European NATO allies. His message was blunt: the US could no longer reconcile its global security commitments with a Europe that failed to invest in its own defence and held divergent views on sovereignty, migration and industrial policy. It was only then that Europe’s rearmament began in earnest. So, what took so long?

Three pillars

Since the turn of the century, the EU’s model of peace and prosperity had come to rest on three pillars: American security guarantees, Russian fossil fuels and, increasingly, Chinese raw materials. It was the availability of these three elements that enabled the bloc to free up extra funds and pursue its remarkable mission of building a welfare continent free of war. Of course, America, Russia and China also benefited from this model.

The Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2014 did not change much. Defence spending in European countries began to increase (towards a target of 2% of GDP over a decade). But the EU largely continued its development as planned, relying on its alliance with America, appeasement of Russia and (deepening) partnership with China.

The first Trump administration with all its red flags came and went. Defence spending continued to stagger upwards, and the EU launched a Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) to deepen defence cooperation. The welcome stability of the Biden administration, however, contributed to a sense of strategic inertia. His administration’s non-confrontational approach to China and ambivalence towards the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline reinforced the perception in Brussels and many member states that no dramatic course correction was necessary. So on it went: America, Russia, China.

One down

Then one of the pillars came crashing down. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine came as a shock to Europe. The EU and European countries provided Ukraine with unprecedented military support, but were beset by obstacles and criticism. They justifiably took pride in possessing cutting-edge technology for state-of-the-art weapons. The weapons, however, mostly existed only in sufficient quantities to show off at arms fairs around the world. Their companies also mainly produced them for export; domestic production was insufficient to meet the needs of member states’ armed forces. It turned out to be more beneficial for Europeans to clear their warehouses of outdated equipment and weapons, transfer them to Ukraine, and buy new equipment from elsewhere, than to sharply increase their domestic production.

In the 1990s, for example, Germany produced around one Leopard tank a day. Two years after Russia’s 2022 invasion, annual production had dropped to only 40-50 units of the most advanced Leopard 2A7 or 2A8 models, despite unprecedented demand. (It also takes on average two years to progress from the order to the delivery of one such tank.) In France, the production of Caesar self-propelled howitzers has increased from 2 units a month before the invasion to around 8, with plans to scale up to 12. Europe’s NATO members—albeit mainly Britain, France and Turkey—spent more than $3trn on defence in the decade to 2023, yet all the tanks, fighting vehicles and artillery pieces that existed by February 2025 in the British, French, German and Italian forces combined would likely not be enough to fend off a Russian attack in the Baltics.

Evidently, the speed and scale with which the EU began to haul its vessel towards matters of defence in 2022 was not equal to the threat confronting the pan-European project. The Treaty of the European Union contained a mutual defence clause, but the continent’s militaries and thus their ability to uphold it had atrophied. The bloc’s founders also foresaw a defence community. But, despite PESCO, the EU’s success as a peace project meant structures like the European Defence Agency that were supposed to coordinate European efforts had fallen into disrepair. There was also variation in public opinion across the EU regarding the level of threat Russia posed and the trade-offs people were willing to make, for instance, regarding whether they thought their country should come to Ukraine’s aid. This intensified as inflation started to bite. The Zeitenwende would have to wait a bit longer.

Even Trump’s return to the White House did not lead to an immediate realisation across the Atlantic that Europe would have to rebuild its defence muscles. That took Vance’s Valentine’s Day breakup speech, and another pillar turning to dust.

One to go

Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014 and in 2022. It interfered in the internal affairs of European countries, conducted cyberattacks and built up its own military capabilities. Europeans transferred large quantities of their weapons to Ukraine. EU member states warned of the threat of Russian military action against them. Moscow escalated on land (North Korean troops, for instance), in the air (Iranian drones, say) and at sea (sabotage in the Baltic, for example). Any of these moments might have prompted a strategic shift in EU policy. But none did.

The EU’s turning point came only when its leaders realised that America was no longer willing to guarantee its security. Of the three pillars that allowed the bloc to build the welfare continent, two—Russian gas and oil, and the American security umbrella have vanished. The bloc’s, by now, dependence on China for materials vital to the energy and defence sectors has become existentially dangerous. Just as the EU was once hooked on Russian gas, it now faces a similar affliction with Chinese raw materials and components. Beijing can thus shatter the final pillar with a flick of the finger.

And so, the EU rushed to adopt decisions that for years had lacked the necessary political backing, even when leaders in Brussels had tried to draw member states’ attention to the need for action. The weeks that followed Vance’s speech saw a flurry of announcements and summits. The European Commission’s white paper on defence preparedness was published, calling for an EU-wide defence market by the end of the decade; commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, also launched an €800m plan to “ReArm Europe”, complete with a loan facility that aims to boost joint procurement. Among European leaders, it once again became fashionable to speak at defence factories and pose among soldiers.

All of this is right and necessary. But the sheer volume of initiatives risks obscuring what truly matters. The success of Europe’s rearmament hinges on the EU directing its action towards three core problems: time (or lack thereof), regulation (simplification and clarification of rules) and relevance (investing in weapons and technology for the wars of the future, not the past).

If the EU does not do this, it could first lose security, and with it, its model of prosperity. Der Untergang (“the downfall”) could replace die Zeitenwende and become the reality of this generation. Europe does not have to abandon the idea of pacifism by arming itself to the teeth. But in today’s world, an armed pacifist may just have a greater chance of survival.

Time

The problem

The EU was created to be deliberative; now it is out of time.

The idea has always been that unity under time pressure is not guaranteed. A slow pace of decision-making, on the other hand, would ensure quality of output and that interests are balanced. However, the reality is fundamentally different now. The EU will have to swiftly come to terms with this to make up for the losses it incurred over decades of reliance on the US; a dependence that resulted in the degradation of European armies and the continent’s overall security architecture.

The lessons

1. 2030 is now the long term.

The NATO secretary general Mark Rutte has called for an alliance-wide commitment to spend 5% of GDP on defence, joining the chorus of voices indicating that Russia may be ready for an armed conflict with Europe by the end of the decade. This timeline roughly coincides with projections for when another wave of EU enlargement might take place. The EU’s revival of its enlargement ambitions was helped along by the geopolitical and security benefits for the EU and for its prospective members. No doubt, war on EU soil would scupper these plans. This means Europe has at best five years to make up for the inaction of the past three decades.

2. The immediate term is crucial for (all of) Europe’s security.

The almost guaranteed absence of a new US military aid programme means that weapons and equipment in Ukraine will gradually be depleted. It is difficult to establish the exact date when this shortage will lead to publicly noticeable consequences on the front. But the count is in months, not years. Some informed Ukrainian officials speak of the end of summer, others of the end of the year.[1] European policymakers should view helping ensure Ukraine can continue to fight as buying the EU time to rearm and reorganise itself.

Still, those who believe that Russia would not dare open a new front while its hands are tied in Ukraine may be in for an unpleasant surprise. Moscow is entirely capable of mobilising for a local operation because the objective would be different. In Ukraine, Russia seeks to subjugate an entire country. Elsewhere, its aim would be to demonstrate to Europeans and the world that EU and NATO unity does not hold. Even a single day of hesitation in Brussels, caused by a lack of consensus among allies and member states over the nature and scope of a military response, would be a victory for Russia. The Kremlin would spin it as proof that both the EU’s and NATO’s defence clauses were fake all along.

3. Ukraine is a live laboratory through which the EU should have learned to respond to these urgent demands.

But the EU has yet to turn this laboratory into a systematic process of learning while treating Ukraine as an equal, integrated partner. Denmark was the trailblazer in this department. The “Danish model” supports Ukraine’s defence industry by allowing Ukraine’s allies to finance locally produced weapons and equipment. For now, this enables Europe to supply more weapons to Ukraine’s war effort, more quickly. In the future, the development of Ukraine’s defence industry with its European partners will help ensure more of Europe’s weapons are “made in the EU”. It is thus an important step towards the integration and autonomy of (all of) Europe’s defence sector.

Nor has the EU learned quickly enough how to communicate the urgency to member states and the European public. Rearmament has become a major policy trend, but the EU still seems to lack a clear, resonant message that can win European governments votes across the bloc. War will not wait for democratic consensus. And unless the EU actively builds that consensus, politicians will hesitate to make the necessary sacrifices. To overcome the problems that plague Europe’s defence industry and ensure the continent’s future military relevance, this will have to change—fast.

Regulation

The problem

The EU was built on complex regulation; now it has to simplify.

Of all the steps the EU will take, perhaps none will match the complexity, importance and consequences for other areas as regulation. The reason for the complexity is that the EU’s very DNA leads it to over-regulate everything. Detailed regulation is not inherently bad. However, it is detrimental to the task of reviving European defence industries from the ruins. European defence companies, for example, often lack financial resources due to banks’ reluctance to lend to the military sector. They also often face difficulties due to complicated and fragmented export restrictions. The EU thus faces a highly complex task: addressing the shortcomings that hinder its defence industry without over-regulating the field.

The lessons

1. Embracing a culture of simplified regulation helped Ukraine’s defence industry thrive.

There is a general and sincere admiration for the Ukrainian drone industry. Its rapid emergence owes a lot to the technological and manufacturing creativity of Ukrainians, multiplied by instant feedback from the front lines that enables the improvement of products. But none of this would have been possible had the Ukrainian government not simplified the regulations for the production and adoption of drones. It is precisely thanks to this that Ukraine created the conditions for a business boom and the growth of drone production from hundreds to more than a million a year (with a target of 4.5 million for 2025). The same task lies ahead for the EU: to simplify the rules and certifications for starting and conducting defence businesses, and the adoption of products into service.

2. The EU cannot achieve this without greater defence integration.

Ukraine is one country, one legal system, one business environment and one set of voters, at war. The EU is 27 countries, 27 legal systems, 27 business environments and 27 sets of voters, in a grey zone that still reads as more real in the east of the continent than the west or the south. Defence sector integration is the only way for the bloc to achieve the culture of simplified regulation that can prepare it for war. This simplification is complicated further by the fact that the EU also has to work with its non-EU NATO allies, such as Britain and Norway, and NATO itself.

The EU will have to develop a vertical system of coherent rules that determine the procedures for ordering, manufacturing, adopting, using and transporting weapons and equipment. Decision-making at summits, directives from the European Commission, strategies and action plans may create the impression that the regulatory framework has been established. It is a delusion.

The real problems begin where a gap exists between the higher and lower levels. A summit of EU heads of state, for instance, may decide that military equipment and troops can move freely across the bloc. But laws made at that level have no bearing on the instructions for the road police of a certain member state. The integration needs to find its way down to that level to prevent movement being disrupted in wartime. This is because, in wartime, delays in movement disrupt military operations and create an advantage for the enemy. Such provisions involve trade-offs that the EU will need to communicate and sell to member state governments.

3. Integration has to cover the weapons systems themselves.

Ukraine has received weapons from many countries in Europe and around the world. This means its forces have had to learn to operate and maintain many different systems of tanks, artillery and air defence systems, not to mention small arms. It has become common among the military to describe this as a “zoo”. The zoo causes problems and delays in training, supply logistics and forces’ ability to respond quickly to changing battlefield conditions. Undoubtedly, it is better to have a zoo than nothing at all. But the EU will have to learn from this to accelerate its movement towards a unified lineup of key types of weapons.

The current European zoo is the result of pride in each individual country in its defence technology and industry. Member states develop various artillery systems with different specifications. The theme continues with armoured vehicles and communications systems. Moreover, part of the reason for the sluggish rate of Leopard 2A7/8 production is that different NATO countries use a variety of models, which affects the supply of spare parts.

The zoo diminishes Europe’s overall combat capability. Besides that, it means the EU misses out on the savings that economies of scale could bring. Fragmentation also slows down innovation, as different countries invest in similar technologies separately instead of coordinating their efforts and creating large-scale projects capable of competing on a global level. And the lack of a unified procurement and standardisation policy creates obstacles for the rapid supply of weapons and military modernisation in case of threats.

Pan-European aerospace company Airbus should become the EU’s model: thousands of suppliers from more than a dozen European countries manage to interact in a coordinated way thanks to a unified product line and a cohesive legal framework. Until then, national egos will continue to weaken the strength of the union.

4. Scalability depends on reliable, resilient supply chains.

Almost every weapons manufacturer in the EU would point to supply chain problems as an obstacle to the stability and scalability of their production. European manufacturers’ dependence not only on weapons but on materials and components from elsewhere is becoming almost as worrying in defence as it is, say, in clean technology. Between 2020 and 2024, European NATO members imported 64% of their arms from the US. China, meanwhile, dominates the supply chain for drones, in which Britain, France and Germany are all investing heavily.

Europe’s rearmament cannot become hostage to fragile global supply chains and exposed to weaponisation in times of crisis. Defence supply chains are critical infrastructure. The EU will have to learn to prioritise and integrate them with the same urgency it applies to its green and digital transitions.

Relevance

The problem

The EU has only known peace; now it faces unknowns in warfare.

Europe’s rearmament began with two political acknowledgments: first, war in Europe is no longer a theory—it is a real, time-bound threat; second, to respond to that threat, the EU will have to turn its ample regulatory powers to integrating its defence ecosystem.

But to be truly ready, the EU will have to use its financial, technological and political capital smartly. The first world war-era French prime minister Georges Clemenceau is often attributed with saying “generals always prepare to fight the last war.” This encapsulates a core dilemma in European defence policy: after finally beginning to mobilise its resources, Europe faces immense pressure to ensure it does not invest them in capabilities that will be obsolete if or when conflict arrives. It also has to do so in a political landscape that largely still operates within a paradigm of peace.

Perhaps most importantly, spending a lot does not mean spending wisely. Even now, the EU collectively spends more on defence than Russia (around €326bn in 2024 compared with Russia’s estimated $149bn the same year). But just look at the difference in outcomes: Russia is fighting the largest war in Europe since 1945, and the EU is not ready to repel an attack in the Baltics. The EU’s spending amounts to about 1.9% of its GDP; Russia dedicates around 7%. Efficiency, focus and urgency, not just the size of the budget, are what truly matter.

The lessons

1. The EU can use its model of peace and prosperity to its military advantage.

The EU has a strong manufacturing base and yet it is in many ways fortunate to be militarily “underdeveloped.” It does not suffer from bloated cold-war legacy forces to the extent the US or Russia does. It has fewer sunk costs. This means the EU has a historic opportunity to leapfrog traditional force design and move directly to “software-defined military”—one in which automation, AI, cyber-resilience, and humans and machines working together are built in from the start, not tacked on decades later.

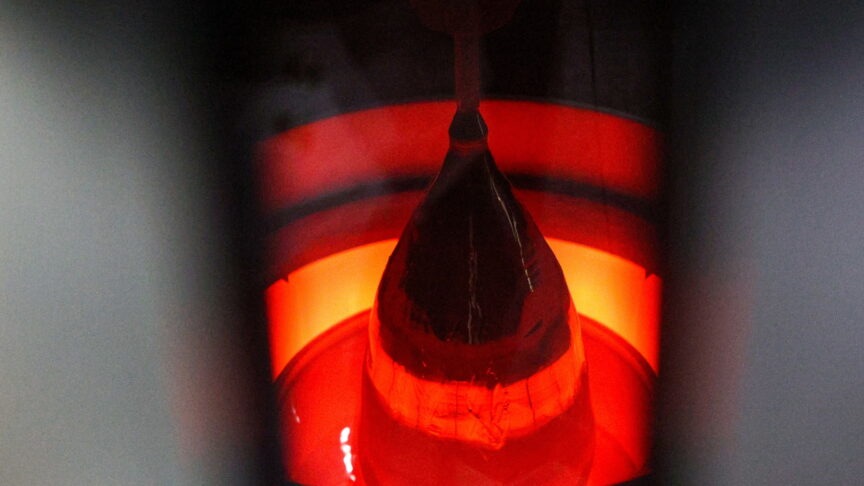

Russia, for example, takes pride in the fleet of strategic bombers it inherited from the Soviet Union. But it can no longer produce them. That is why the losses Ukraine inflicted in Operation Spiderweb are irreversible. Russia also had vast stockpiles of tanks and armoured vehicles, but they quickly went up in flames on the battlefield. Soviet-era production capacities are too slow to replenish them. The reason is simple: in today’s warfare, heavy equipment is destroyed faster than it can be built.

Russia’s drone sector tells a different story. With Iran’s assistance, Russia has built Shahed drone production from scratch in just two years. According to Ukrainian military intelligence, in autumn 2024 Russia was producing 500 of these drones a month; at the time of writing, that number had risen to 2,700. This leads to another lesson: it is easier to build new production than to overcome the inertia of leadership in old structures. Europe must learn this if it does not want to spend hundreds of billions of euros and remain unprepared for modern warfare.

2. Warfare changes faster than procurement systems.

The Ukrainian military’s ability to adapt in real time created strategic advantages. The evolution of Ukraine’s anti-tank strategy illustrates this perfectly, and provides valuable lessons for the EU.

In the early days of Russia’s full-scale invasion, the Ukrainian armed forces and their Western partners relied on classic anti-tank missiles such as the American Javelin. Each such system costs approximately €200,000, and they were extremely effective against Russian tanks and armoured vehicles in 2022. Over time, however, new solutions emerged. Loitering munitions like the Switchblade 600, at around €80,000 per unit, allowed Ukraine’s forces greater flexibility and target selection.

Then came the transformative use of First-Person View (FPV) drones. These devices, often retrofitted by Ukrainian soldiers in garages, could be deployed in swarms. Five FPV drones costing just €1,000 each (and sometimes even less) could destroy a €5m Russian tank. In two years, the cost of eliminating a tank dropped from €200,000 to €5,000 (a 40-fold reduction). Operation Spiderweb, in which small drones destroyed and damaged massive aircraft, has taken this to a whole new level.

The lesson here is not simply the triumph of cheap over expensive. FPV drones are not technological marvels—they are commercially available devices, weaponised through creativity, necessity and decentralised initiative. This kind of battlefield improvisation will never be possible in a rigid, top-down bureaucracy. If the EU wants to be relevant, it will have to embrace: modularity (quickly adaptable weapons and supplies that can keep up with innovation); flexibility (amending slow, bureaucratic processes to allow for rapid adjustments in tactics, procurement and deployment); and front-line integration (incorporating feedback from the front lines to enable innovation).

Still, drones cannot replace the infantry soldier. The machines can eliminate enemy personnel in a trench, but only a soldier can hold that trench. They must physically occupy it, defend it and receive logistical support to remain effective. As such, all high-tech solutions must ultimately serve one basic operational truth: forces have to take ground and hold it. The drone’s real value lies in enabling the infantry, not replacing it.

Europe’s relevance therefore hinges also on building integrated systems in which soldiers, sensors and shooters work seamlessly together. A good starting point is the French “Scorpion” programme, which aims to digitise the entire battlefield and connect all units in a “combat cloud”. The same is true of AI-enhanced targeting, “battlefield mesh networks” (decentralised wireless networks) and their accompanying portable battlefield command systems (the hardware). Rather than building individual platforms, Europe will have to build interoperable warfare ecosystems, tailored to NATO and EU doctrine but agile enough for contested environments.

3. Technological relevance is only half the equation.

This is not the first time EU leaders have attempted to establish joint European defence programmes. Previously, these have faltered due to numerous political obstacles.

First, EU countries have different strategic interests. This makes the coordination of large defence projects difficult: Germany, for example, traditionally followed a cautious defence policy; France has long sought a more active role in international security. Several dozen PESCO projects are under way, including the development of a next-generation European tank, a military transport system and joint cybersecurity initiatives. But PESCO’s effectiveness is limited due to some countries’ reluctance to delegate parts of their national defence capabilities to joint structures.

Second, the EU’s political challenges mean, right now, there is no point talking about a “single European army”. It is impossible for Europe to create a unified army without first making progress on unified weaponry, logistics and regulatory frameworks for that army. Moreover, if the US remains in NATO, it will likely resist any European competition to its thriving weapons manufacturers. If the US ever left the alliance (which even now seems improbable) then the EU should simply take over NATO and continue to develop it as a European and Canadian project.

Third, the EU cannot escape the question of public perception and what message can turn rearmament into votes. Before anything else, people need to know what exactly the EU is preparing for; or the benefits of building up an advanced and relevant defence ecosystem risk remaining abstract for voters. It could be a defensive war against potential Russian incursions or greater involvement in Ukraine’s war effort. It may also include expeditionary crisis-response missions in Africa or the Middle East under the UN flag, or contingencies in the Red Sea or the Taiwan Strait, where vital sea lanes and supply chains are at stake. Another interpretation is deterrence through enhanced presence and posture. Most likely, it is a combination of all these objectives. But European citizens need to know that military might is not a luxury: it is the foundational prerequisite for the EU’s model of prosperity.

How the EU can adapt its hardware for war

European leaders need to change their perception of time, regulation and relevance. This is no longer just a strategic adjustment—it is the only path to helping Ukraine win, preparing the EU for war and making Europe a stronger actor in a world it still hopes to shape.

Short-term urgency

The EU’s deliberative nature means many of its immediate-term choices have been made for it.

Conduct a confidential dialogue with Ukraine

EU and member state leaders, alongside Britain and Norway, should conduct a confidential dialogue with Ukraine to model the timelines of its forces’ use of weapons and equipment, and projected volumes of available supplies. They should undertake this with the presumption that the US will cease to be the main provider of military assistance to Ukraine. The parties should then build a feasible timeline for the production and delivery of weapons. They must then stick to this timetable.

Invest more in weapons production in Ukraine

More European countries should follow the Danish model and invest in weapons production in Ukraine. This will reduce immediate production costs and shorten the delivery time to the front.

Conduct “damage limitation” diplomacy with the US

The “nuclear option” for the Trump administration would be to block European countries from transferring weapons manufactured, purchased or containing technology or spare parts from the US (or other third countries) to Ukraine. The EU and European countries need to maintain diplomatic efforts and connections with the US to ensure any such “worst case” scenario does not come to pass. In the longer term, while Europe needs to build autonomy from the US in defence, it should maintain diplomatic relations whatever the future holds.

Introduce “industrial conscription”

The EU should consider an “EU Preparedness Act” that would enable it to compel large companies to repurpose part of their production lines for dual-use capabilities and military contracts. In the meantime, European governments should incentivise companies to do so of their own volition.

Smartly prioritise new defence spending

The EU and its European NATO allies should increase the proportion of their defence spending that is earmarked for research and development (R&D). In 2023, the US spent around 15% of its military budget on R&D and innovation. Direct comparisons are difficult due to different ways of defining R&D internationally and among EU member states (which often include procurement in the same category). But the same year, member states seem to have allocated only around 4% of their defence budgets (€11bn of a total of €279bn) to R&D. Greater investment in this area is necessary not only for the EU’s military relevance, but will also produce bigger savings in the longer term.

Medium-term reform

The EU’s penchant for regulation means it is well placed to improve the continent’s defence integration.

Work towards a unified defence market and industrial integration

This has long proven elusive for the EU. But now its leaders’ perception of time is starting to change; they should prioritise action on the following five steps to ensure their momentum is directed where it will be most beneficial:

-

Establishing a European system of weapons standards.

This is without question a massive technical undertaking. But, with the necessary political will, the EU and its member states, the UK and Norway can and should begin to establish such a system. They will have to coordinate with NATO to do this and ensure the interoperability of these standards with that of the alliance (see below). -

Strengthening the coordination of defence orders.

The EU should establish a unified defence procurement coordination centre. This centre would have the task of managing the financing and distribution of defence orders. Again, this will help lower costs and accelerate deliveries. -

Developing financial instruments to incentivise private investment.

The EU should aim for greater involvement of private investment in defence to help overcome the reluctance of banks to lend to the sector. The bloc should develop special financial mechanisms to incentivise investors to fund defence enterprises. The EU also needs to continue its efforts to accelerate the allocation of funds to defence industries. -

Streamlining the process for defence sector exports.

The EU needs to unify its rules for defence exports. The current fragmentation among member states hinders the growth of its defence industries. But the EU would need to underpin this with a legal and ethical framework to offset the risks and concerns such streamlining may create among member states. -

Integrating Ukraine’s industrial base into that of the EU.

The EU should integrate Ukraine’s defence industrial base to the extent that it becomes part of the common market, even before Ukraine’s accession as a full member state. This would allow the EU to access a unique industry and an innovative regulatory culture that the bloc needs to build up its own. Ukraine, in turn, would benefit from access to Europe’s resources and the opportunity to integrate its technologies.

Address supply chain dependencies and bottlenecks

The EU has passed legislation and launched financial instruments to address its dependencies in clean technology and semiconductors. These include the 2023 Chips Act, the 2024 Critical Raw Materials Act and the 2024 Green Deal Industrial Plan. It now needs to develop a similarly ambitious framework for defence.

This could come under a “Defend Europe Act”. Whatever the name, the aim of the legislation should be to map dependencies, support the domestic production of critical materials, establish joint procurement pools for critical components and build strategic stockpiles across the EU. The EU’s external action service, and national diplomacies and intelligence services will need to work together to secure these networks in the long term.

Increase alignment with NATO (yes, really)

Alignment between the EU and NATO is insufficient, leading to overlaps and redundancies in the two entities’ responsibilities. It will not be easy for the EU or NATO to address this thanks to institutional egos. But they will still have to do it.

The EU should focus on creating a unified defence market and fostering industrial integration. NATO can complement this with an emphasis on capability development and interoperability. Such coordination will need to involve regular consultations and joint planning to ensure that regulatory frameworks support industrial efficiency and strategic defence objectives.

Moreover, the European and US defence industries need to standardise their processes and establish mutual recognition of certifications. The EU should align its efforts to standardise its defence procurement and certification with NATO’s capability targets and interoperability requirements. The EU should work to achieve this through PESCO projects that align with NATO’s strategic goals. By addressing these issues, the EU and NATO can create a more cohesive and resilient transatlantic defence industrial base, ultimately enhancing the security and defence capabilities of their member states.

Long-term relevance

The EU’s underdevelopment in defence means it can jump straight to the future of warfare.

Create a “Schengen of military technology”

The EU needs a radical regulatory carve-out for defence innovation. It should aim for this to act as a “Schengen of military technology”, within which projects move without national regulatory barriers. The EU could develop this as a “Deep and Comprehensive Free Defence Area” (DCFDA).

Within this area, the EU should enable the mutual recognition of companies’ certifications, streamlined export controls and harmonised security protocols. This would speed up the development, testing and adoption of defence technologies. Startups, SMEs and consortia alike would operate under a single legal framework, preventing the duplication and bureaucratic delays that currently hamper collaboration. The DCFDA should include fast-track exemptions to bidding regulations for defence procurement. It would also need to encompass a pan-European security clearance framework and include mobility provisions for defence-sector talent.

The initiative could function as a voluntary measure under Article 44 of the Treaty on the European Union. This would allow coalitions of willing states to integrate their efforts without full EU unanimity. The DCFDA would not only boost Europe’s defence readiness but also have the additional benefit of signalling to the world that the EU is serious about boosting its defence and autonomy, while leaving broad room for engagement with allies and partners.

Make hard power a vote winner across the EU

The EU should build its core narrative on the assumption that Europe’s security will be guaranteed only when politicians begin to win elections with promises to protect Europe, not to increase social benefits. As Ukrainians have learnt, the framing of Ukraine as a “shield” protecting Europe has limited public impact in many member states: it may be emotionally compelling, but it does not translate into strategic urgency. The stronger message is that Ukraine is buying time for Europe; failure to use that time wisely will result in war crossing EU borders, possibly within five years.

There are ways to translate this message into action. Politicians should embrace the defence agenda as a signal of strength and prosperity. All major EU-funded defence projects should include a strategic narrative and communication component aimed at building public understanding and support. This could include simulations, digital storytelling, school programmes and cultural partnerships to restore the societal prestige of defence and security.

Turning bugs into features

The EU was not created for war, nor to be fast or simple. Now, it not only exists in a state of “unpeace” and faces an unknown future of warfare, but it has next to no time left to undertake complex processes of simplification. And yet, few if any of the world’s institutions do regulation better than the EU; its underdeveloped defence ecosystem means it can jump straight to the future of warfare. In short, both the problems EU leaders need to fix and their solutions lie within the very essence of the union.

Weapons have been—and largely remain—a matter of national pride and “high” economic policy. But, if most EU countries were able to give up their beloved national currencies in favour of the euro because it made them collectively stronger, then they can achieve the same when it comes to defence. Moving there is a matter of urgency and mindset. Then there will be a reason to discuss a European army: integration across everything else will make it easier for national armies to fight together for their countries and Europe as a whole if or when the time comes.

About the author

Dmytro Kuleba is a distinguished policy fellow with the European Power programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Kuleba served as Ukraine’s foreign minister from March 2020 until September 2024. During his tenure, he played a pivotal role in strengthening Ukraine’s diplomatic ties with Western, African, Asian and Latin American nations and was a leading advocate for increased aid to Ukraine in response to Russia’s invasion. Kuleba has been particularly prominent in advocating military assistance for his country.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his gratitude to Kim Butson for her outstanding editing, and to Mark Leonard for creating the ECFR community—a space that fosters the exchange of ideas, the sharpening of arguments (some of which made their way into this policy brief), and their wider dissemination.

[1] Author’s conversations with Ukrainian officials, Kyiv, May 2025.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.