La Hongrie au sein de l’UE : autrefois un fervent défenseur, maintenant un obstructionniste

Une victoire convaincante de Victor Orban renforcera le rôle de veto hongrois dans l'UE. Cependant, le pays n'a qu'une influence marginale au-delà de son voisinage sur les politiques de l'UE.

A convincing victory for Victor Orban will reinforce the Hungarian veto role in the EU. However, the country has only marginal influence beyond its neighbourhood on EU policies.

Whatever its effects on Hungary’s economy and society, the April 2018 Hungarian election will have significant implications for Europe as a whole. A convincing win for Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party will reinforce the veto role the governments of Hungary and Poland have designed for the Visegrád group in the European Union. Triggered by their opposition to the EU’s refugee policy but based on a much broader resentment of Brussels-based governance, Warsaw and Budapest have become champions of the sovereign counter-narrative to “more Europe”. They face less opposition within the Visegrád group than they once did. This is because the Slovak government is in crisis; the strongman of Czech politics, Andrej Babiš, is struggling with fraud charges relating to EU subsidies; and Miklos Zeman, who is openly sympathetic to nationalist and populist views, has been confirmed as Czech president.

Orban’s Coalition against more Europe

Assuming he is re-elected, Orbán will seek to broaden this coalition by reaching out to Romania (despite the Magyarian rhetoric that complicates relations with Bucharest). As the governing Social Democrats work to contain anti-corruption efforts, they could use the veto coalition to counter possible EU attention. Orbán may also reach out to the Austrian government of the conservative Austrian People’s Party and its deeply eurosceptic coalition partner, the Freedom Party. Both governments’ preferences on migration might serve as the core of an informal alliance that works to halt or reverse the EU process of pooling national sovereignty. Orbán, Jaroslaw Kaczynski – head of Poland’s governing Law and Justice Party – and other political leaders stand for the notion of majoritarian democracy, which centres on the “will of the people” as expressed in elections. They regard that will as a legitimate basis for undoing the constitutional separation of powers – not least by politicising the judiciary – and limiting individual freedom and minority rights. It is likely that Italy’s next governing coalition will be somewhat open to adopting this kind of discourse and approach.

A resounding electoral victory for Orbán could accelerate the anti-Brussels coalition building.

Such is the nature of the deepening rift between the EU’s east and west, which is shaping the debate on the reform of the organisation’s policies and institutions, as well as the recently begun negotiations on its Multiannual Financial Framework, which will apply from 2020 onwards. A resounding electoral victory for Orbán could accelerate the anti-Brussels coalition building as much as a defeat or small majority could curb the Visegrád group’s momentum.

Hungary’s paradox: strong structural cohesion and weak individual cohesion

Hungary once adopted a leadership role in European integration – opening the border between eastern and western Europe, while rapidly adopting a market economy and transitioning towards democracy – but the pendulum seems to be swinging back. On both counts, the Hungary of the 1990s was a Musterknabe (front runner). However, ECFR’s analyses of cohesion and coalition-building in the EU reveal that Hungary feels less European and is less connected to western EU states than had been widely assumed.

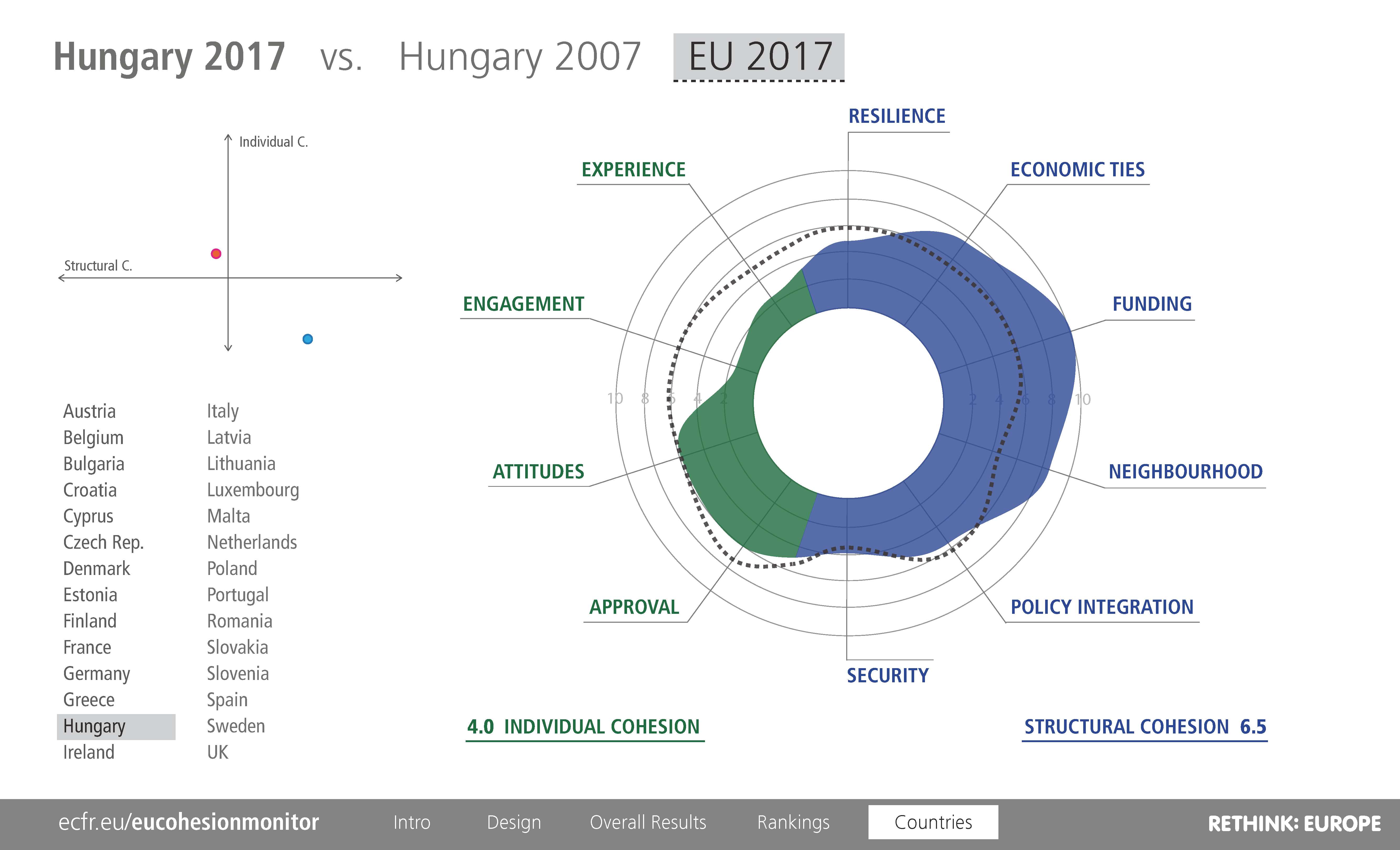

According to the EU Cohesion Monitor, which measures the strength of factors that contribute to EU countries’ willingness to cooperate with one another, Hungary is the most visible EU accession success story in eastern central Europe. The country has experienced a massive increase in structural cohesion, yet continues to have low levels individual cohesion. Indeed, ECFR’s 2017 data shows that Hungary has the lowest level of individual cohesion of all 28 member states. The country’s integration in the EU has had little effect on its citizens’ connections with other Europeans. Since Hungary joined the EU in 2004, financial transfers from the organisation’s budget have increased structural cohesion in the country more than any other member state. In the EU Cohesion Monitor, Hungary’s funding indicator grew by 7.3 points (on a scale of one to ten) between 2007 and 2017, outpacing both the Czech Republic and Poland (whose indicators grew by 5.2 and 4.4 points respectively). By comparison, Bulgaria’s and Romania’s funding indicators grew by 7 points and 6.4 points respectively.

Hungary’s economic ties with the EU were strong before 2007, the first year in which ECFR gathered data for the EU Cohesion Monitor, and even before it joined the organisation. They have maintained a high level of economic cooperation ever since. However, during the past decade, factors that increase cohesion between Hungarians and other EU citizens have weakened slightly since 2007. Hungarians’ have less personal experience with European integration almost any other national population in the EU – a level similar to that of Bulgarians and Romanians. Thus, while Hungary benefits massively from projects that Brussels has co-funded, its citizens are largely detached from the EU. In the EU Cohesion Monitor, Hungary had an individual cohesion score of 4 points in 2017; by comparison, Slovakia – which has greater individual cohesion than any other Visegrád country – had a score of 5.9 points that year.

Hungary’s coalition profile: a regional networker with no outreach

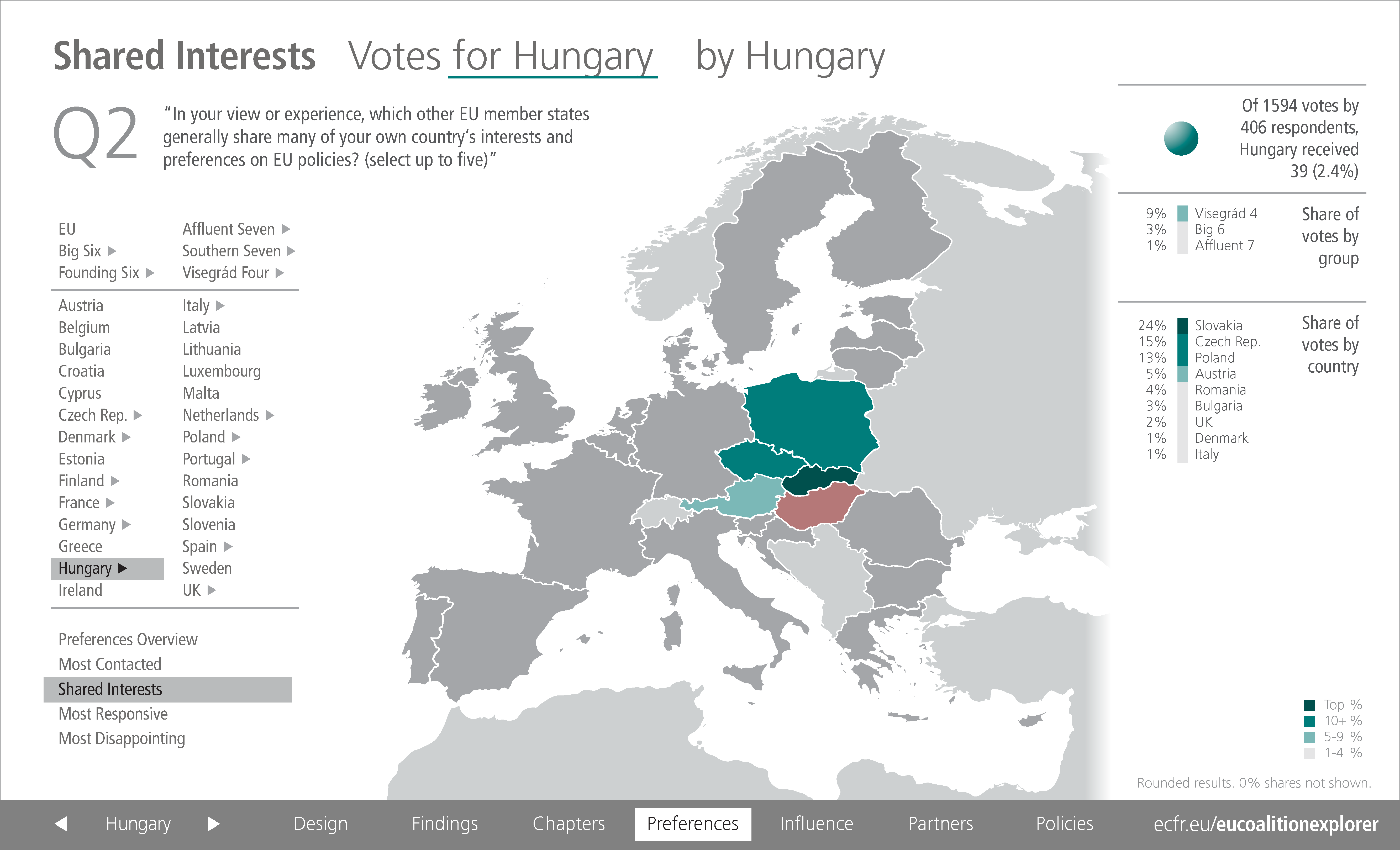

Budapest’s interactions with other European capitals are also mismatched with EU-Hungary economic interdependence. Politically, Hungary focuses primarily on its immediate neighbourhood and has very weak ties beyond this area. According to bureaucrats and think-tankers within the country, Hungary prefers to concentrate on interactions with other members of the Visegrád group, particularly Poland and Slovakia. They also perceive Germany and, to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom as important interlocutors, but not ones that share Hungary’s interests. However, neither German nor British policy professionals show reciprocal interest in Hungary. Aside from Poland and Slovakia, all of Hungary’s fellow member states describe it as a disappointing coalition partner (the UK, Poland, and Greece are similarly unpopular in this regard). Meanwhile, largely due to disagreements over migration policy, Hungary expresses most disappointment in its partnership with Germany, followed by France, Austria, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Greece.

Download Hungary's complete country chapter from the EU Cohesion Monitor here.

Only other members of the Visegrád group regard Hungary as an essential partner. Some member states view the country as important on certain issues, such as Austria, Slovenia, and Croatia on foreign policy and security, and Romania on security and economic and social policy. Similarly, Hungary’s perceived essential partners are other Visegrád members and its neighbours (the only exceptions being Germany and the UK, as noted above).

In sum, Hungary is a regional networker with strong ties to neighbouring countries. However, the country has only weak influence beyond its neighbourhood; although it works to engage with Germany and the UK, the former pays little attention to Hungary and the latter is leaving the EU. In all likelihood, Budapest’s ability to organise an EU caucus that opposes German policy preferences is its most important tool for forcing Berlin to address its concerns.

Hungary is a regional networker with strong ties to neighbouring countries. However, the country has only weak influence beyond its neighbourhood.

If the views of Hungary’s bureaucrats and think-tankers generally reflect those of its political class, the country is more wary of European integration than most other EU member states. These professionals prefer to deal with a range of EU and foreign policy issues on a national basis rather than within the organisation as whole or sub-groups of member states. In Hungary, organisations pursuing greater European integration receive little support, but there is relatively widespread backing for the eurozone and, to a lesser extent, the Common Foreign and Security Policy and EU energy policy. Hungary is an outlier on the EU’s common Russia policy. Like Greece, it expresses strong reservations about the policy – a position that it may have adopted due to the bargaining power that could flow from establishing special relations with Russia. In Hungary, the proposal for a common EU border police and coast guard has significant support (in contrast to those on common asylum, migration, justice, and home affairs policies) but is polarising: proportionally, more Hungarians reject the proposal in favour of a national approach than any of their EU counterparts aside from the British (26% and 30% respectively). Hungarian bureaucrats and think-tankers only appear to support “more Europe” on key issues such as the single market, climate policy, and European defence.

Nonetheless, public opinion could hardly be used as justification for the Orbán government’s euroscepticism. According to an EU-wide poll ECFR commissioned around the time of its survey of the EU Coalition Explorer, the Hungarian public generally has a more positive view of the EU than Hungarian bureaucrats and think-tankers.

Given these trends, Hungary will likely maintain its approach of weakening the EU to prevent the organisation from interfering with national policies. Obstruction will remain an important tactic for Budapest as it works to gain the attention of, or extract concessions from, other member states. Nonetheless, Budapest will try to avoid biting the hand that feeds it, particularly in relation to financial flows. In this context, the negotiations on the Multiannual Financial Framework will set the margins of Hungarian manoeuvrability. Should net contributors to the budget and reform-minded countries build a strong coalition, they will test the power of the Visegrád group. Orbán himself could abandon his opposition to Brussels if he is forced to choose between financial benefits and the veto.

Read more on: Wider Europe,Western Balkans,European Power,Cohesion & Governance,National Politics

L'ECFR ne prend pas de position collective. Les publications de l'ECFR ne représentent que les opinions de leurs auteurs.