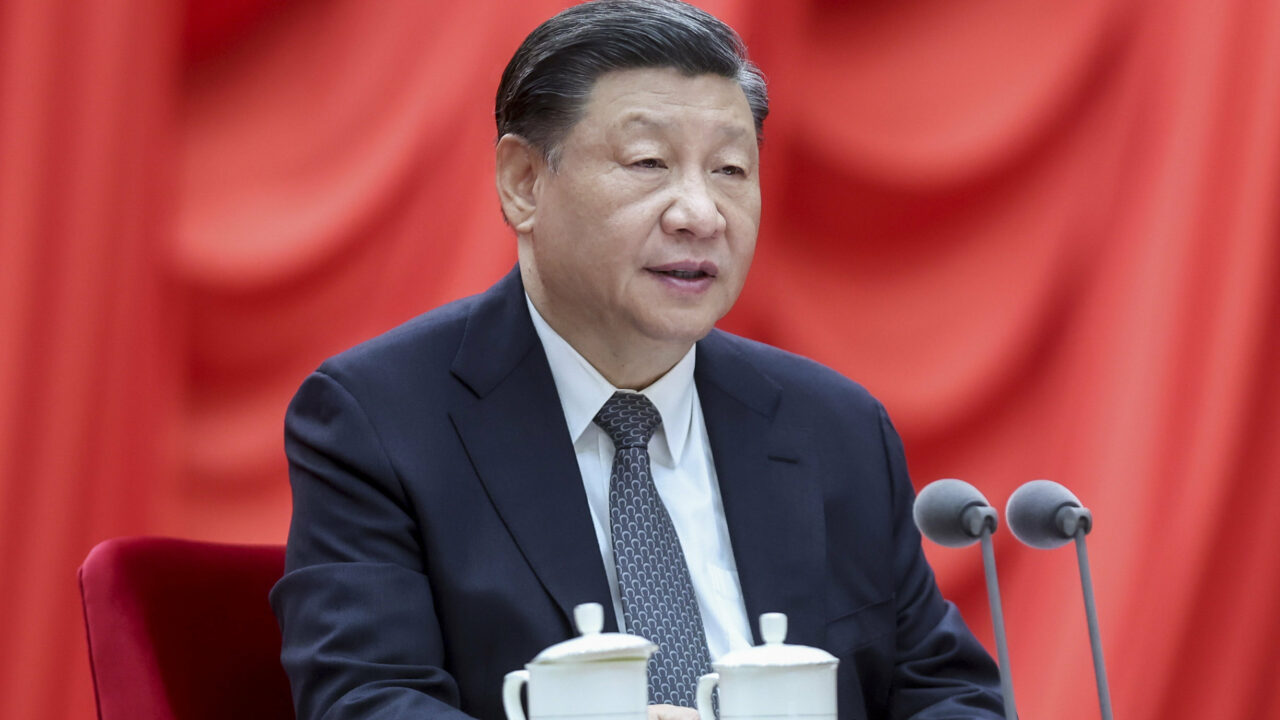

Xi Jinping’s idea of world order

The real battle for international supremacy today is not between democracies and autocracies, but between different models of global order, with China and the West each offering its own distinct account of “democracy”. The sooner that Western leaders recognise this, the better chance they will have of attracting new partners

By all accounts, Chinese president Xi Jinping has had a successful few weeks. Hot on the heels of the Chinese-brokered restoration of diplomatic ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, he used his recent visit to Moscow not only to shore up relations with his close (junior) partner, Vladimir Putin, but also to present a “peace plan” for the war in Ukraine. As The Economist put it, these events have opened a window onto the “world according to Xi”. Meanwhile, Xi’s travels have incited much Sturm und Drang across the West, which itself may be heading toward a strategic dead end.

After all, the emerging consensus among Western policymakers follows from several assumptions that may lead them to act in counterproductive ways. Specifically, Western leaders believe that they are defending the rules-based order from revisionist powers such as Russia and China; that the world is polarising between rule-bound democracies and aggressive autocracies, with swing states in the middle; and that we need better narratives to convince others that Russia’s attack on Ukraine has significant implications for them. But each of these claims is problematic and speaks to a misunderstanding of the challenge China represents.

First, the idea that Western governments are preserving the rules-based order is not persuasive to many around the world, considering that Western governments themselves have already abandoned it on many fronts. While Russia and China obviously have been challenging the post-1945 international order, many across the so-called global south would say that Westerners, too, have routinely revised international rules and institutions to suit their own interests.

These observers would point out that the first hammer blows came with the Western-led intervention in Kosovo and invasion of Iraq, not with the subsequent Russian invasions of Georgia and Ukraine. The West may not be using military force today, but it has not held back from using economic instruments to its advantage – from sanctioning anyone who trades with Iran and Russia to proposing taxes on developing countries through carbon border adjustment mechanisms.

Moreover, in some areas, Western countries have moved from revising global institutions to abandoning them altogether in favour of what is often portrayed as a new “rich man’s club” built on novel concepts like “friend-shoring”. Many leaders around the world enjoy highlighting such hypocrisy, compounding the West’s legitimacy crisis.

Countries like India, Turkey, South Africa, and Brazil see themselves as sovereign powers with the right to build their own relationships, not as swing states obliged to placate other powers

The second assumption is even more problematic. The US president, Joe Biden, has committed himself to the narrative that the world is divided between democracies and autocracies, implying that those in the middle should be persuaded or pressured to choose sides. But most countries reject this idea and instead see the world moving toward deeper fragmentation and multipolarity. Countries like India, Turkey, South Africa, and Brazil see themselves as sovereign powers with the right to build their own relationships, not as swing states obliged to placate other powers.

The third assumption therefore is also flawed. It is not because of narratives that we cannot persuade others that the Russian invasion is wrong; other countries just have different interests. Most developing countries and emerging economies do not regard Russia’s war on Ukraine as an existential threat, whatever the West may say. If you live in Mali, the dominant external power with which you are most familiar is France; if anything, Russia’s entry into the mix will give you a greater sense of sovereignty, not less. Similarly, India is much more fearful of domination by China; if anything, its relationship with Russia represents a strategic opportunity.

The problem with the account promoted by Western governments is that it has allowed China to steal a march on them. From China’s perspective, the real battle for supremacy today is not between democracies and autocracies, but between different accounts of what “democracy” means.

For Biden and other Western leaders who fear that China’s rise will overturn the Western-dominated global order, the best response is for democracies to come together to counter China and maintain their own edge. The Biden administration thus aims to create a club of democracies that trade together, share technology, and stand up for each other’s security.

By contrast, China – whose only treaty ally is North Korea – realises that it cannot win a contest between competing alliances. Xi’s strategy therefore is to appeal to the non-Western world’s general preference for optionality and non-alignment. Presenting himself as the champion of these principles, he has developed a different notion of “democracy” based on the ability of all countries to emancipate themselves from Western dominance. This concept featured heavily in his rhetoric when he met with Putin in Moscow.

The contest between these two visions is deliberately asymmetrical. While the United States is betting on a polarised world, China is doing everything it can to advance a more fragmented one. Rather than trying to replace the US, it wants to be seen as a friend and ally to developing countries that want to have a greater say.

There are plenty of reasons to doubt that China can pull off this strategy. In those parts of the world where Chinese influence has grown the most – namely, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa – it has often triggered a backlash. And, looking ahead, China will be competing with India for leadership within the global south. Nonetheless, Chinese leaders are probably right to suspect that sovereignty – rather than obeisance to more powerful allies – will be the defining theme in 21st century global politics.

Given China’s strategy, Western policymakers should adjust their approach. Instead of lecturing (or hectoring) non-Western countries, they ought to acknowledge that everyone has their own interests, which will not always align perfectly with Western interests. Heterogeneity must be accepted as a structural fact, rather than being framed as a problem to fix.

By being less preachy about how other countries run their affairs, and by treating them as sovereign actors with their own priorities, the West can still effect constructive change on specific global issues – and maybe even pick up some new supporters along the way. To present a compelling alternative to Xi’s vision of world order, the West will have to stop asking others to defend the existing one, and start recruiting partners to build on a new vision.

This article was first published on Project Syndicate on 30 March.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.