It’s the (geo)economy, stupid: Why the EU-India deal matters beyond trade

The EU and India have just concluded the biggest trade deal in their respective histories. Europeans will benefit from lower tariffs with the G20’s fastest-growing economy—and potentially game-changing geoeconomic ties

At the EU-India summit in New Delhi, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen and India’s prime minister Narendra Modi announced the conclusion of a much-anticipated trade deal that drastically reduces bilateral tariffs in many key industries.

European sectors like automotive and machinery will see tariffs progressively slashed from prohibitive 110% or 40% rates to 10% or 0%. For India, traditionally a highly protectionist country, it is a huge liberalisation commitment and highly generous compared to the deal it signed in July 2025 with Britain, reflecting the European Union’s larger economic leverage.

Mother of all deals

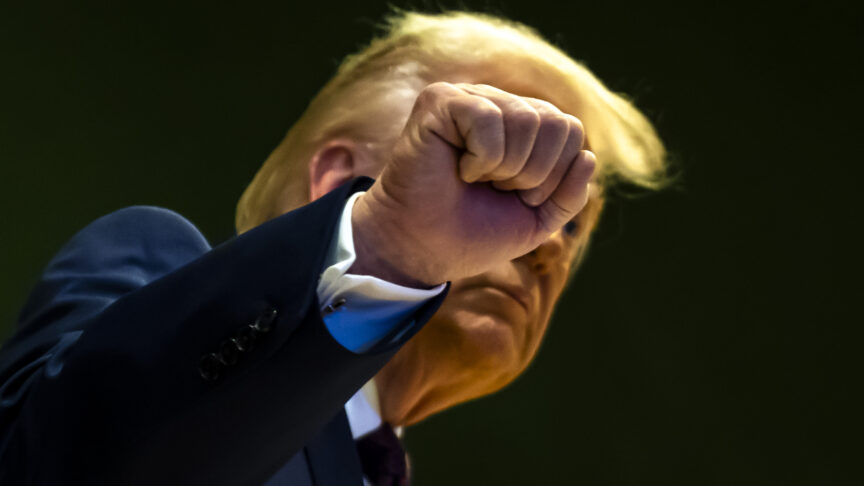

Both sides have an unlikely (and unwilling) patron in US president Donald Trump. If the 20-year negotiations produce a meaningful deal after more than a decade of lull, the EU and India can thank Trump’s tariff hikes against New Delhi, his close leaning to Pakistan and his continuous threats against European countries—ranging from custom duties to outright territorial annexation.

America’s wavering has been instrumental in pushing the EU and India to agree on a deal that only recently seemed difficult to reach. India, faced with US tariffs, is pushing for certainty in its trade relations, while Europe is seeking diversification to reduce reliance on an increasingly erratic American administration.

But despite both sides hailing the free trade agreement as the “mother of all deals”, at first glance it carries more rhetorical and political value than economic relevance for the EU. After all, India barely makes into the top 10 of EU trade partners; in 2024 the bloc exported more to Norway than to India, despite the Nordic country’s GDP being nine-times smaller.

On top of this, the phase-out of tariffs for the automotive sector will take a decade, during which EU exporters will still see high duties for vehicles outside the agreed quotas. The deal also excludes several products from the highly protected Indian agricultural market. It will not lift tariffs on sensitive goods like dairy, cereals and poultry, although India will slash prohibitive tariffs on alcoholic beverages and olive oil.

Furthermore, the deal will really deliver for both signatories only once other areas of friction such as sustainability standards are properly addressed. Add to this the geographic distance between Europe and India, and Europeans might question how such a deal could really be a gamechanger for the EU, even if the expectation that bilateral trade will double by 2032 were to materialise. Really, what makes it truly relevant?

Safeguarding trade and dividing BRICS

In reality, this deal is about much more than bilateral trade. For Europe, it is the first step towards building a broader partnership with the fastest-growing G20 economy. The deal is essential to safeguard a global multilateral trade system being torn apart by US tariffs, Chinese export restrictions, and other unilateral measures. In such a context, the best strategy is to build a wide and diversified network of partners to maintain predictable and open trade among its members. The EU-India trade deal does exactly this by bringing 25% of the global population under a shared trade system.

However, the most important value of this deal is geoeconomic: India and Brazil are the BRICS member most strongly resisting Beijing’s (and Moscow’s) attempts to turn the bloc into an anti-Western alliance. Despite its looser structure and internal rifts, BRICS provides a key coordination platform for countries challenging the US-led global governance system. Its members account for more than 40% of the global population and 24% of global trade. By 2050, the group is forecast to double its GDP and surpass the G7.

While China and Russia want to establish an alternative system, India and Brazil are looking to safeguard multilateralism, despite making changes to better reflect the shifting global balance of power. Now the EU-India trade deal is set to become Brussels’s best tool to consolidate its partnership with New Delhi. It might also prevent India from falling into China and Russia’s more anti-Western camp.

Rising powers are Europe’s key

The EU-India trade deal is hot on the heels of Mercosur. Instead of decrying the end of a world order from which they benefitted, Europeans are finally embracing their trade strengths

Europeans are facing a rapidly aging population, a declining share of global trade and a highly troubled transatlantic relationship. Now they must look outside their borders to consolidate their economic strength.

This means building effective partnerships with rising powers who share concerns about rules-based trade, technological disruption and economic security to establish a global network. Europe, together with these players, represent a geoeconomic pole with the power to shape global affairs.

The EU-India trade deal is hot on the heels of Mercosur. Instead of decrying the end of a world order from which they benefited, Europeans are finally embracing their trade strengths. They have started to build a new system which allows them to remain central in the world of tomorrow.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.