How China is undermining digital trust – and how democracies can respond

A ‘whole stakeholder approach’ is key to taking on and defeating online disinformation

People around the world today benefit hugely from the information and communication technology present in our lives. We can chat with friends using social networking sites and make online payments with a swipe of the finger. We receive information through the internet that keeps us up to date and helps us make decisions. This means that cyber attacks and disinformation and malinformation campaigns are a threat not only to our economic activities, but also to society at large. Ensuring that citizens using ICT have “digital trust” in the security and reliability of the online world is key to ensuring broader societal trust.

China has for some time recognised that a country which controls networks and information on networks can assure the hegemony of those in power. The Communist Party of China’s core goal is to guarantee its own ongoing rule, and it knows that continued economic growth is vital to securing the support of the Chinese people. Keeping control of the digital economy and related technologies is thus central to this, including seizing a dominant position in the international community economically, diplomatically, and militarily.

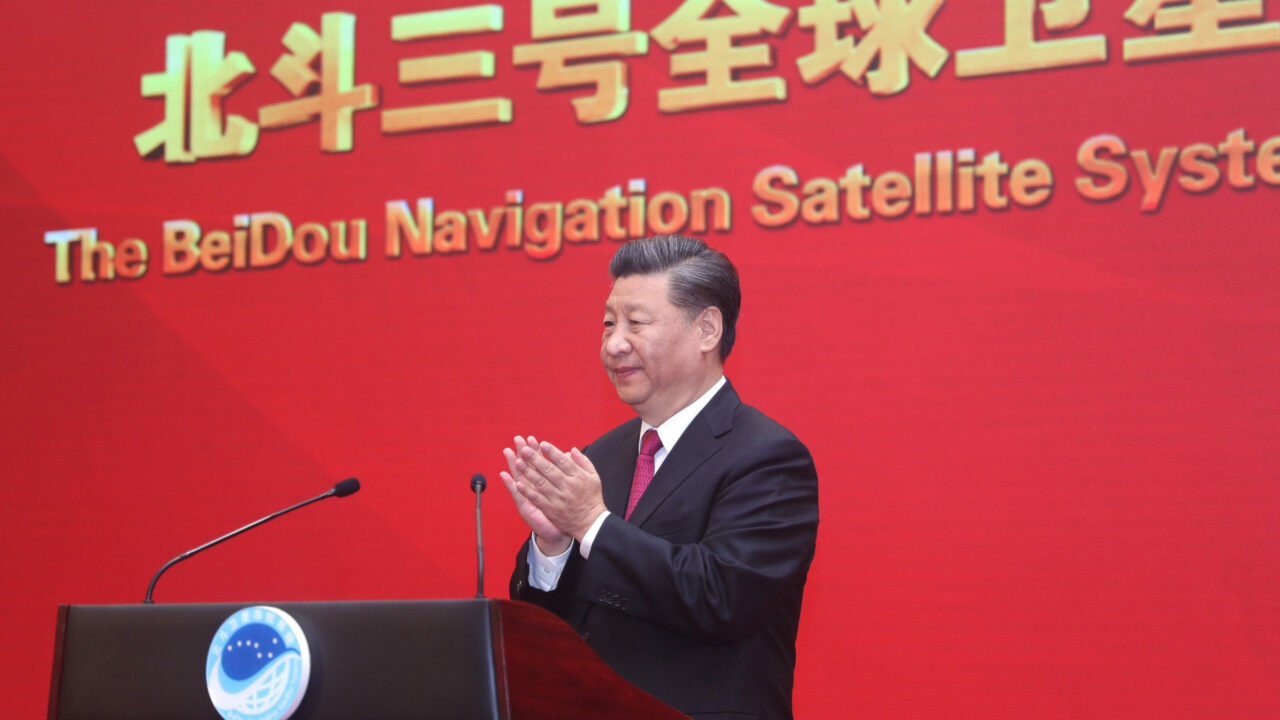

Disseminating Chinese ‘standards’ in telecommunications and other online technologies to other countries is a mean to achieving this. China can use these ‘standards’, spread along with services such as China’s GPS system, Beidou, to increase its influence over the digital economy in those countries that adopt them. The Chinese government will likely this year release what it terms “China Standard 2035” – its plan to define what rules the next generation of technology around the world must follow.

The country is already heavily investing in network-infrastructure and next-generation technologies such as AI, 5G, “big data management”, and cloud computing. China is building up satellite networks in outer space – more than 40 new satellites were launched by 34 rockets in 2019, while 102 rockets were launched globally that year. Recently, China has also aggressively expanded its undersea cable network, with the United States in 2019 warning this constitutes a threat.

Such networks and the services that run on them will give China control over information, the opportunity to manipulate information, and to conduct offensive cyber operations and effective disinformation campaigns. Disinformation campaigns in particular are difficult to detect.

Countries concerned at this prospect can learn much from Taiwan’s experience of counter-disinformation operations. According to media reports, the Taiwanese presidential election in January 2020 saw a massive disinformation campaign from China to sabotage the re-election of President Tsai Ing-wen. The Taiwan government took a ‘whole of society approach’ to its counter-disinformation operation. Specifically, Taiwan adopted the following three methods, as identified by analyst Aaron Huang.

- Monitoring media platforms closely and seeking to debunk fake news when it emerged. As Huang notes, “The government often used memes to disseminate the correct information publicly, recognising that successful online viral content tends to be short, funny, and easy to understand and share” Moving quickly was an essential part to the success of this strand of work.

- Raising public awareness of propaganda and disinformation. The government focused on education, such as by, for example, organising fake news identification workshops.

- Adopting an Anti-Infiltration Law to “deter Chinese interference in the elections and frame them as a referendum on Chinese penetration into Taiwan.”

Democracies need to continue to develop the capability to detect and neutralise disinformation campaigns.

Although this has proved effective, it will not always be possible to implement whole of society approaches, and not all political contexts will be as well suited to these. There may be technical approaches, which democratic societies can also adopt, such as defining a piece of disinformation by detecting the identity of the information organiser. However, this requires a large number of analysts and access to high-performance systems. Moreover, disinformation operatives take measures to avoid being detected by anti-disinformation operations.

Monitoring how quickly something spreads through a network may be another means. To illustrate: traditional media, such as newspapers and television, confirm evidence before they publish news. Disinformation, however, often spreads rapidly through some social networking sites, before traditional media has yet reported, precisely because there is no evidence. The pattern of information spread can thus flag to authorities the presence of potential disinformation.

Institutions such as Keio University SFC Institute have just started making efforts on this front. Democracies need to continue to develop the capability to detect and neutralise disinformation campaigns. A government must integrate all stakeholders – its cabinet, ministries and agencies, military forces, domestic society, foreign governments, and international organisations – to conduct counter disinformation operations, taking a ‘whole stakeholder approach’, not only a ‘whole of society’ approach. The whole stakeholder approach must integrate and address all of the key issues and events in digital activity, including cyber attacks and disinformation campaigns.

Democratic countries will increasingly need to cooperate each other, because safe and free access to networks and correct information are global commons. However, it is important to understand the situation in each country before conducting cooperative operations between countries. A combination of study, discussion and table-top exercises would be an effective way to achieve mutual understanding and securing digital trust.

Bonji Ohara is a Senior Fellow at The Sasakawa Peace Foundation in Tokyo, Japan.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.