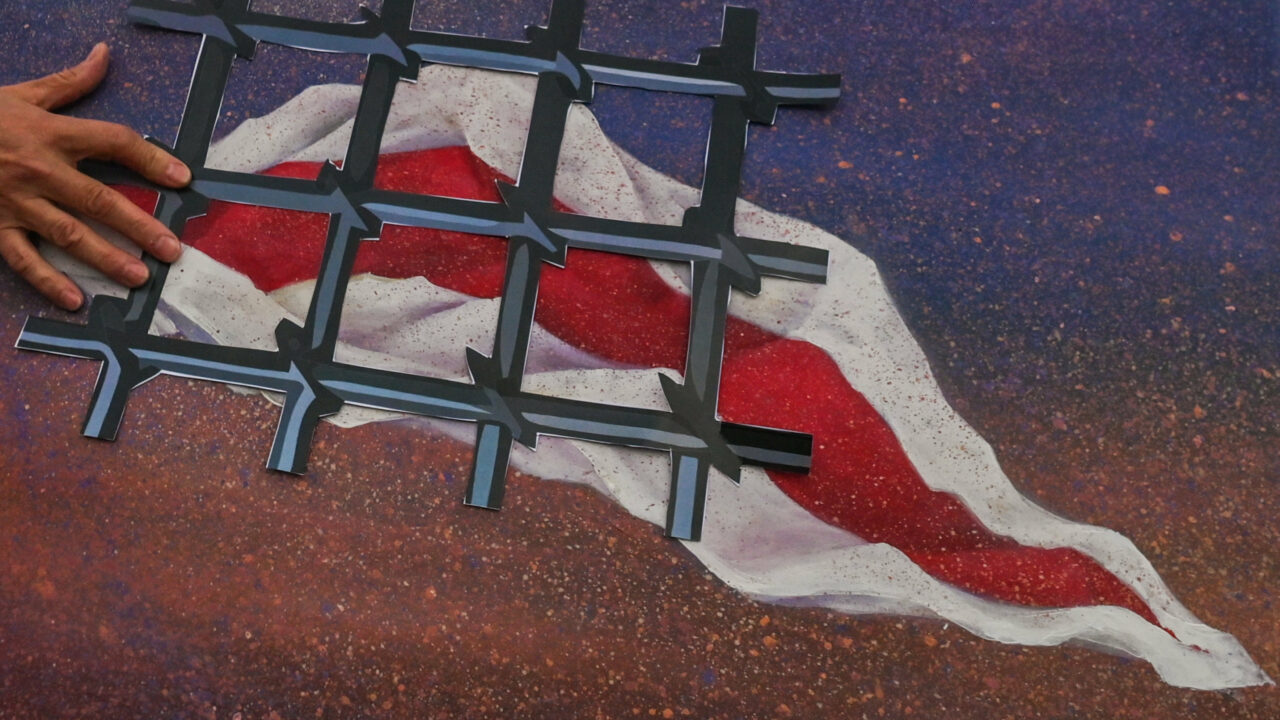

Freedom’s gambit. How to save Belarusian prisoners of conscience

Just beyond the borders of the EU, the prisons of Belarus hold thousands of hostages of the Lukashenko regime. There is no magic formula for their release, but the EU can draw on international examples to save the lives of at least some of them

There are currently 1,471 political prisoners in Belarusian prisons, while more than 1,150 individuals have already completed their sentences. Once released, many are compelled to flee abroad immediately in order to avoid re-detention. Former prisoners speak of the torture conditions they experienced in prison, including beatings, coerced confessions on camera, being marked with yellow tags, and the deprivation of basic necessities such as mattresses, warm clothes, underwear, toothbrushes, and even toilet paper. Cells for political prisoners are doused in bleach, windows are left wide open in winter, and up to 16 people are placed into four-bed cells. The unsanitary conditions frequently make political prisoners ill, and the administration denies them medical care, leading to deaths and suicides.

Roll back to only February 2020, and Belarus had no political prisoners – and the country was not an international pariah. It regularly hosted European and American delegations, had liberalised domestic policies, and was opening up for foreign business and tourists. Now, there are more political prisoners in Belarus (with its population of 9 million) than there are in Iran (population: 88 million) or Venezuela (population: 28 million).

The question of how to free Belarusian political prisoners has divided the democratic opposition into three camps based on their strategies for release. One camp advocates the continuation of sanctions on Lukashenka, demanding a comprehensive solution that includes the release of all prisoners and an end to repression. They argue that, without these measures, the regime will simply continue to fill its prisons with opponents.

The second camp views sanctions as ineffective, having failed to influence the regime’s behaviour, all while people slowly die behind bars. They suggest lifting sanctions, negotiating with Lukashenka, recognising his legitimacy, and ransoming hostages or making other concessions to secure the freedom of at least some prisoners. They point to the examples of Switzerland, the United States, and Israel, all of which have brokered deals with Lukashenka for the sake of their citizens’ release. Switzerland appointed an ambassador to Minsk, who presented credentials to him. As US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo telephoned Lukashenka. Israel did both of these – by presenting credentials, it recognised the legitimacy of Lukashenka, despite the rigged presidential election of 2020. President Isaac Herzog discussed “humanitarian issues” in his call with Lukashenka.

The third camp is represented by Belarusian volunteers fighting for Ukraine. They believe that neither sanctions nor concessions will bring results. They say that a time of war requires military methods: they want to strike deals exchanging Belarusian political prisoners for Russian soldiers and Belarusian mercenaries captured in Ukraine while fighting for Russia.

A common challenge across each of these approaches is that none of the camps has control over the things that could actually secure prisoners’ release. Sanctions are imposed and lifted by Western institutions; credentials sit in the hands of Western ambassadors; and the exchange of prisoners of war is orchestrated by Ukraine. The Belarusian democratic movement in exile lacks the tools and resources to force Lukashenka to act or secure favourable agreements with him. They can only make appeals to Western capitals.

European diplomacy has a crucial role to play in aiding the liberation of political prisoners. Returning citizens taken hostage by hostile regimes is historically challenging, but not impossible. The US unfroze $6 billion of Iranian funds to secure the release of five US citizens from Iran. It also spent five years securing the return from Venezuela of seven wrongly detained US citizens. France and Germany have successfully negotiated the release of hostages from Iran.

In some cases, diplomatic involvement by foreign states has helped extricate some individuals from the clutches of the Belarusian regime

In Belarus, virtually none of the 1,471 political prisoners possesses a foreign passport, and there is no one to trade for all these people. However, in some cases, diplomatic involvement by foreign states has helped extricate some individuals from the clutches of the regime. For instance, the Polish government successfully negotiated the release of at least 10 Belarusian citizens of Polish origin. Thanks to the involvement of the US State Department, Radio Liberty journalist Aleh Hruzdzilovich was also freed.

Other EU states should take up this practice. Over the past three and a half years, negotiations targeted on specific individuals have shown the greatest effectiveness. The release of individual prisoners does not require a change in the general line of EU foreign policy, which is to maintain both the international isolation of the illegitimate regime and sanctions against Belarus. However, tactical minor concessions can at least bring freedom to some individuals, including those on the brink of life and death. Belarusian citizens convicted of spying for the benefit of the Russian and Belarusian authorities abroad can also be used in exchanges.

Such negotiations should involve countries that have smooth relations with both Western allies and the Lukashenka family – the UAE and Qatar, for example. These countries are considered custodians of the Lukashenka family’s wealth and, therefore, have enough authority for him to use his influence. In May 2023, Qatar helped secure the release in Rwanda of political prisoner Paul Rusesabagina (who was also the hero portrayed in the film Hotel Rwanda).

Modern history provides examples of larger-scale liberations. In 2022, possibly fearing tougher US sanctions, Daniel Ortega’s regime in Nicaragua agreed to release 222 political prisoners following negotiations with Washington. The authorities there loaded prisoners onto a plane and sent them to the US. Whenever Lukashenka eventually agrees to free Belarusian political prisoners, Western powers should have agreed a host country or countries to take them.

Unfortunately, the problem of political prisoners is not unique to Belarus. Estimates suggest that tens of thousands to a million political prisoners languish in prison dungeons worldwide, from Cuba to China. In most cases, their fate depends much more on the goodwill of those who arrested them than on the activity of foreign states. However, it is our common responsibility to stand up for those illegally taken hostage, whether they are held by Hamas or by dictatorial regimes in Europe.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.