Security through politics

Europe should not confine itself to adopting a narrow security-driven approach in Libya

Libya has gradually emerged as one of Europe’s worst headaches. After the fall of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, public opinion and opinion-makers alike considered Libya to be riven with chaos, anarchy, and violence; it was known as a source of uncontrolled migration and terrorism. Yet, despite these concerns, Libya rarely made it into high-level conversations between national leaders and little effort was made to help steer the country in the right direction. This changed in late 2014, when the threat of an Islamic State group foothold close to European shores and the continuing anarchy put the north African country back on the list of European worries.

2012 and 2013 were years of fatal mistakes by the post-Gaddafi leadership. First, militias were given government salaries, and they then quickly moved to take control of what was left of government institutions. Second, no reconciliation process was launched while a particularly strict lustration law effectively excluded a large portion of the population from politics and the civil service. This resulted in increasing levels of anarchy as the country lacked a proper security sector while instead having a collection of rival militias on the government payroll. Meanwhile, the lack of political reconciliation led to increasing political divides. This eventually resulted in the building of rival armed coalitions in mid-2014: the anti-Islamist and Egypt-backed Operation Dignity, led by renegade general, Khalifa Haftar, and the radical, pro-Islamist Libya Dawn militia, which eventually took control of Tripoli.

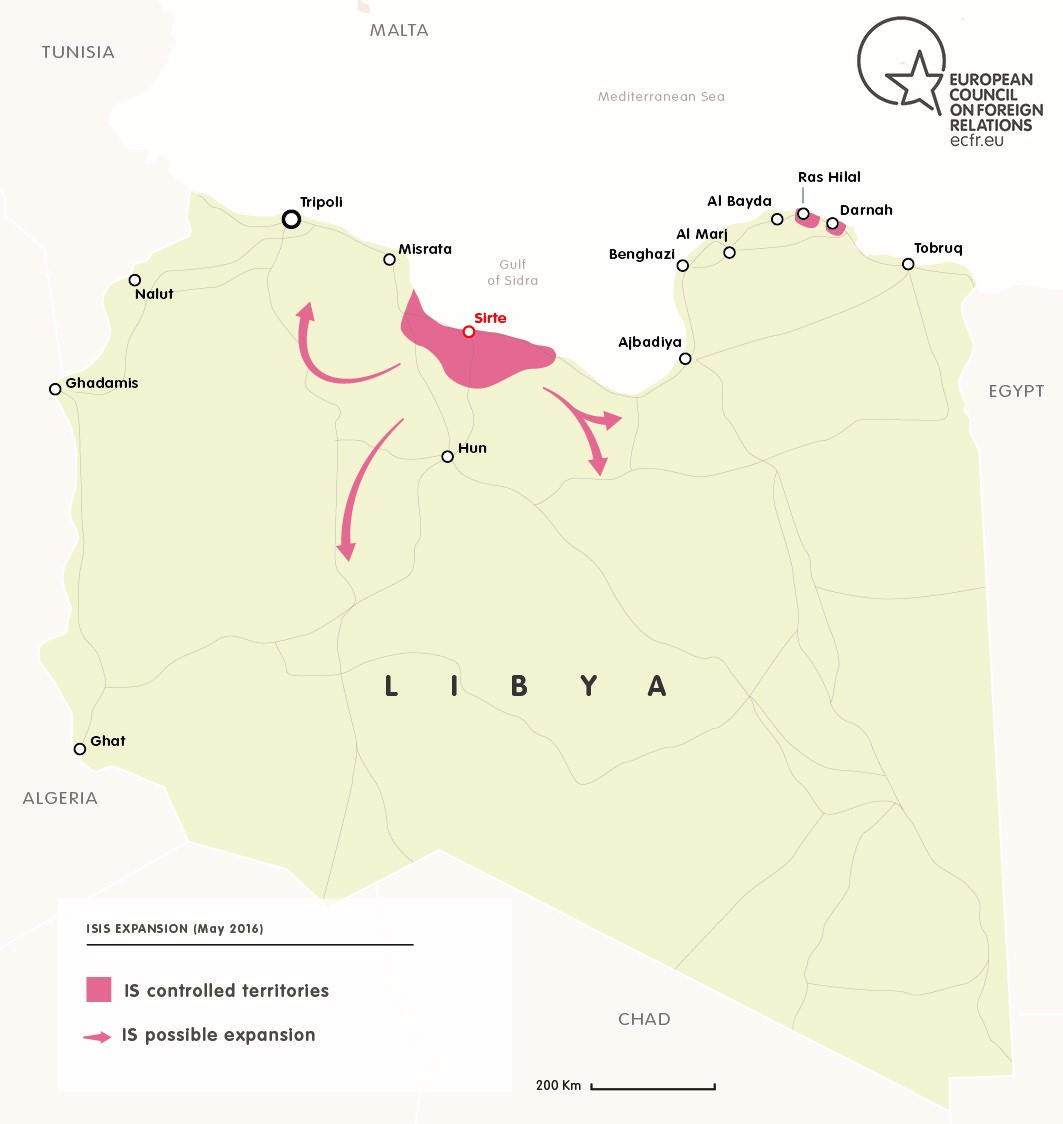

After the Libyan government left the capital, a rival government was created in Tripoli by Libya Dawn, and the country slipped into a low-intensity civil war that is ongoing today. At the same time, ISIS gradually expanded its foothold, establishing territorial control of over 200 kilometres of Mediterranean coastline in the summer of 2015. By this point, containment and neglect of Libya were no longer an option for European policymakers.

European efforts, often in conjunction with the Obama administration, went in two directions. First, large European Union member states, including the United Kingdom, France, and Italy converged on the need to prioritise a political process that would lead to the creation of a national unity government. This eventually resulted in the United Nations-brokered Libyan Political Agreement signed in Skhirat, in Morocco, and endorsed by the UN Security Council in December 2015. Second, the US and Europeans supported Libyan anti-ISIS Operation Bunyan al-Marsous with both airstrikes and special forces. An EU naval operation, named Sophia, was deployed to fight people smugglers in the Mediterranean. The EU Border Assistance Mission (EUBAM) was stepped up and became a Common Security and Defence Policy mission – albeit with a very narrow mandate. It was criticised by several EU members.

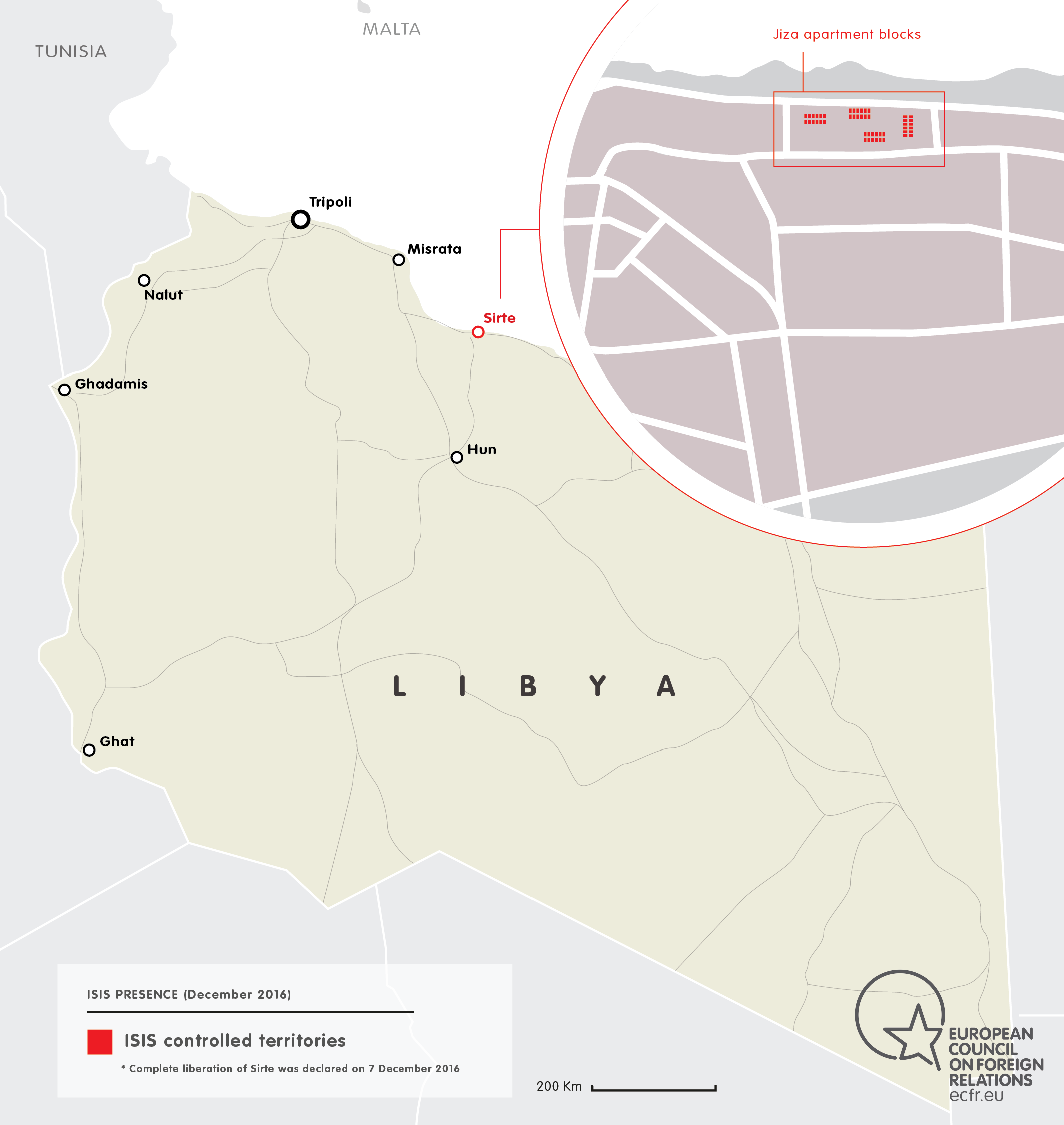

These combined efforts were not a magic wand but they did achieve some results. There was a reduction of violence almost everywhere except for the city of Benghazi and some other areas. Generally, Libya did not reach the levels of casualties of Syria or Yemen and ISIS’s territorial control ended in December 2016, with its fighters either fleeing the territory or dying in combat, dealing a big blow to the organisation’s narrative. The internationally recognised government is now based in Tripoli, although two rival governments still exist and implementation of the United Nations-brokered agreement is stalling. Irregular migration is not under control and Europeans are trying to go beyond Libya by working particularly with Niger and other neighbouring countries.

Overcoming these problems will be key both for Europeans and for Libyans. Rebuilding unified governance is essential. It is not simply about having a unity government but also about having a single central bank, a single National Oil Corporation, and ultimately avoiding a situation in which duplicate bureaucracies respond to different governments without actually controlling the country. Unfortunately, a new and more inclusive political agreement is unlikely to be concluded any time soon as the positions of Haftar and his opponents grow further apart and the regional splits in the Persian Gulf and beyond get deeper and deeper.

For many European governments, it would be easier to find a single interlocutor, whether Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj in Tripoli, or Haftar, or a combination of the two. But no single actor can control all of Libya, and hence be a reliable partner to address Europe’s concerns.

The difficulties of the political process should not lead Europe to adopt a narrow security-driven approach. Libya cannot be dealt with by letting regional powers compete for power and influence while occasionally using air strikes to hit ‘the bad guys’, as the prevailing approach of the Trump administration seems to be.

Instead, the EU and particularly the most active countries such as France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Malta, should adopt a multi-pronged stabilisation approach. As in many other fields of foreign policy and security, cooperation with the UK, despite Brexit, will be essential. First, the EU or a coalition of member states should push the Libyan parties to reach an agreement to share natural resources in order to eliminate one of the main drivers of conflict and avoid a humanitarian crisis. Europe, as the main buyer of Libyan oil and an important financial partner for Libya, has relevant leverage and interests in this field. For Libyan politicians and businessmen, the threat of an EU asset freeze and travel ban is still highly pertinent. Second, the EU should support municipalities and existing institutions in providing public services. Third, Europe should strengthen, support, and extend local ceasefires to reduce levels of violence and the potential for escalation. Fourth, the EU should promote the disbandment of militias and the building of a national army from the bottom up. In this sense, the recent establishment of seven ‘military regions’ could be an opportunity to build local ‘security tracks’ through UN and EU mediation efforts.

For every crisis and conflict in the Middle East and north Africa there is always the temptation, in most capitals, to look for the ‘ultimate deal’ and therefore to push for a political process regardless of its chances of success. But the ultimate yardstick for judging the success of a policy should be how many human lives have been saved and how much it has improved the living conditions of the local population. Stabilising Libya will ensure the country is a less fertile ground for radicalisation and terrorism. At this stage in Libya, the road to achieve that is to focus on stabilisation efforts even in the absence of the ‘ultimate peace deal’.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.