What Russia thinks of Europe

Since 2014-15 “the West” has been overwhelmingly seen in Russia as an enemy seeking to undermine and destroy Russia

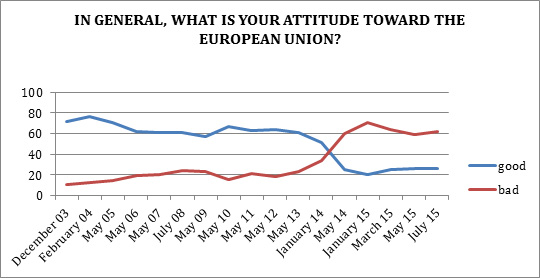

Throughout the 2000s the proportion of those expressing a positive perception of Europe remained way above those expressing a negative one in Putin’s Russia.

There was a short-term narrowing of the gap between the two inspired by the Georgian War in 2008, but the war proved to be short-lasting and relations between Russia and the West soon normalised with the new White House administration opting for a “reset” with Russia. The gap promptly widened again, and for another five years Russians thought generally positively of Europe.

Then, in 2014 the proportion of those with a positive view dropped dramatically and the negative proportion shot upward. They crossed momentarily, and negativity continued to climb. By early 2015 a public opinion poll showed that 70 percent of Russians took a negative view of Europe with just 20 percent still positive about it. The perception is even more negative of the US, but both the US and EU share the same dramatic shift in recent years.

This dynamic is, of course, related to the aggressive anti-Western propaganda campaign that has accompanied the crisis in Ukraine, the annexation of Crimea, and the bloody war in Donbas. Among Russians, state-controlled television rapidly and effectively inculcated a sense that their country was a fortress under siege – with enemies all around.

Though this mindset is a product of Kremlin propaganda, it is not necessarily unfounded. Since spring 2014 Europeans and the US have pursued a policy of sanctions couched in the language of punishing Russia to hurt its economy. The deeper the confrontation and the longer Europe and the US have pursued the policy of sanctions, the more the Russian people are unwilling to look at Europe as a separate actor from the United States.

Indeed, in Russia’s president Vladimir Putin’s rhetoric, Europe is not sovereign, or rather, European countries can’t afford to be sovereign because they are dependent on the US for their security and therefore, can’t pursue independent foreign policies. He says:

“For a number of European nations, national pride may be a long forgotten concept, and sovereignty is something they can’t afford. But for Russia genuine state sovereignty is an absolutely necessary prerequisite for existence”

Yet while it is difficult to eliminate foreign policy considerations from the general perception, outside the political sphere, the perception of Europe is softer than that of the United States. In 2015 almost thirty percent thought of European countries as “neighbours and partners” with whom Russia should develop better relations, not much different from earlier years. The word “European” remains – as it has been through centuries – an outright positive term that implies civilisation, culture, progress or good taste and one for which Russia has a long history of emulation.

Two decades of post-Communist development: From uninformed infatuation to informed appraisal

In the late 1980s, during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, the West, the Soviet Union’s cold-war adversary suddenly became its friendly partner and a model of “normal” life. The “normal” was associated with different things for different people, but the idea that the Soviet Union should follow the western way was widely shared.

The perception of the West was one of uninformed infatuation. In the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union western models were emulated in many spheres of life. The new Russian constitution drew inspiration from the national charters of western countries; the political system was reformed to follow the principles of western democracy; the Soviet planned economy was abandoned in favor of a western-style market; the newly designed Russian media carefully reproduced the best formats the West had to offer; pop-culture and consumption were strongly influenced by western patterns.

But in Russian society at large, the hardship and turmoil of the early post-Soviet years led to a steady disappointment in westernising reforms. Indeed, the belief that the West had intentionally lured Russia into that trap in order to further weaken it was not uncommon among Russians.

When Putin rose to power at the very end of the 1990s he aimed to maximise the benefits of doing business with the West, but also to secure Russian sovereignty. Putin himself did his best to charm and impress foreign leaders, his government worked to attract foreign investment, but at the same time it took steps to reduce western influence, the dependence on western financial organisations, and the presence of western economic advisers, democracy promoters and non-government organisations.

The Orange revolution in Ukraine in 2003-04 made Putin more suspicious of Western influence. He saw those events as an attempt by the West, acting through non-governmental actors, to execute regime change in a country that Russia regarded as within its legitimate sphere of interest.

Putin was increasingly exasperated by the American hegemony: he condemned the United States’ policy of democracy promotion, which he saw as a mask for interference with other countries’ affairs; the United States’ policy of NATO expansion in eastern and central Europe; and its military interventions.

He repeatedly sought to drive a wedge between United States and Europe and so in 2003 he allied with France and Germany against the war in Iraq. His 2007 Munich speech was a passionate attempt to condemn US policy in the eyes of Europeans, but the “united front” between Europe and Russia opposing the war in Iraq proved to be a one-time success.

In the 2000s, thanks to the rapidly growing price of oil, Putin’s government was able to deliver stability and prosperity to his nation. For Putin this created an opportunity to secure unchallenged political power. Among the social effects of those “fat years” was a rise of a new constituency of modernised Russians concentrated in large urban centers, first and foremost in Moscow.

Moscow turned into a bustling cosmopolitan place attracting young and ambitious people looking for lucrative career opportunities, especially in business and finance. The Russians who had graduated from the best economics and business schools abroad would compete for jobs in Moscow where salaries were higher and life was fun.

In an interview with me, Sergey Makhin, a 30-year-old Russian who currently works for an investment company in London, said:

“Russia was a very attractive destination for the Russians who worked abroad as it provided better career opportunities, financial rewards… very importantly I did want to bring all the experience I received here and put it for the benefit of my country.

“Working in London with its high cost of living and high taxes was not as easy as I expected it to be, particularly in 2008-2009, when the financial system was falling apart and bankers were laid off left and right. I felt pretty envious looking at my friends and colleagues back in Russia who enjoyed low income tax and fast career progress, as the economy was expanding and the country continued to experience lack of professionals in the economy”.

Many young, open-minded, entrepreneurial Russians travelled to the West, mostly to Europe, to gain new experience – professional and otherwise – and enjoyed the opportunities of study abroad, internships, academic work, and cooperation with western colleagues

Meanwhile, a sizable minority of the Russian businessmen learnt to take advantage of the many opportunities of the Western world: not only good schooling for their children and comfortable lives for their families in European countries, but also the western rule of law as they drew on western arbitration to resolve their business disputes. Indeed, a 2012 study showed that more than half (57 percent) of all Russian companies either made no business transactions whatsoever in the Russian jurisdiction, or reduce their number to a minimum.

And the advantages of the West were eagerly used too by civil servants who benefitted from their administrative power and converted it to personal wealth (put simply engaged in corruption), but preferred to keep their assets – and not infrequently, their families in the West.

This all amounted to a rather large-scale westernisation and modernisation – most palpable at individual levels, those of consumption and life-style of the Russian urban dwellers. This was no longer the uninformed infatuation of the late 80s and early 90s, but an informed appraisal of the opportunities the West had to offer.

Elements of social modernisation, such as growing taste for charitable work, civic initiatives and organisation could also be traced. In 2012 the Russian journalist Katerina Krongauz, who had herself actively engaged in charitable activities, wrote:

“Donating money for a person in need of expensive surgery or clothes for the homeless, buying New Year presents for the lonely, reposting the information about a person in need, taking part in a charity dinner, making bank transfers to a charitable fund, taking children to a charity New Year matinee, standing in pickets, leaving change in a box for sick children, giving free classes for refugees, participating in a search for missing persons.. — inconspicuously, but steadily charitable and volunteer work has been on the rise.”

This westernised constituency, though significant in numbers, remained a minority, but one that was relatively free of pressure from either the more conservative majority or the Kremlin which remained permissive and did not seem to mind or care.

Urban protest and the Kremlin’s response

It was this constituency of urban, modernised, “European” Russians that found itself at the core of the anti-Putin protests that erupted in Moscow in December 2011 following the announcement of Putin’s comeback to the Kremlin and the fraudulent parliamentary election of December 2011.

As soon as Putin returned to the Kremlin, however, the government moved to discredit and neutralise the excessively modernised trouble-makers who dared challenge his power. The state-controlled media condemned westernised urbanites as immoral and unpatriotic. The Kremlin propaganda and scores of loyalists referred to them as the “fifth column” and “national traitors”. The West itself was portrayed as a political adversary and a threat to Russia’s “traditional values” and aesthetical norms .

The Kremlin’s conservative shift was reinforced by a series of new laws aimed at restricting ties that linked Russians to the West. Before too long the propaganda effort created an image of an “indivisible evil” in which the West is merged together with its domestic “agents” – liberals, westernisers, recipients of foreign grants, gays, contemporary art and its fans – and those who would not treat the Russian Orthodox Church with due respect or would not see Russia’s historical record as unblemished.

The anti-western campaign gained huge momentum after the annexation of Crimea was followed by western sanctions. The West’s retribution for a “misdeed” (the annexation of Crimea) that an overwhelming majority of Russians regarded as their nations unambiguous triumph and a reinstatement of historical justice gave a huge boost to the anti-western sentiments. In March 2014, despite the steadily deteriorating economy, Putin’s approval rating exceeded 80 percent.

In his address to the Russian parliament in December 2014 Putin said:

“The policy of deterrence was not invented yesterday, it has been always conducted toward our country for many years, always, … for decades, if not centuries… Every time somebody considers Russia is becoming too powerful and independent, such instruments are turned on immediately. But talking to Russia from a position of strength is meaningless.”

Since 2014-15 “the West” has been overwhelmingly seen in Russia as an enemy seeking to undermine and destroy Russia and the need to protect the nation against this evil force is now well ingrained. In the minds of most Russians, this applies not just to the realm of defence and security, but also to culture and values that have to be protected against the destructive forces of the western immorality and decadence.

The amazing success of this propaganda campaign suggests that that it touched upon deep-seated sentiments– dormant in some and more active in others. As those sentiments were activated and reinforced this created an “ideological” and emotional demand that was followed by a virtually unlimited supply.

Russia’s Uncertain Identity

The reason for the effective inculcation of the anti-western sentiments lies in the sense of frustration over losing the Cold War, and Russia’s uncertainty over its new identity in the post-Cold War world.

After the Soviet Union collapsed Russia, as its successor, evolved from this crisis as a nation that had lost its sphere of influence and evolved as a smaller and weaker nation. It is frustration over this inferiority that has colored the perception of America much more strongly than that of Europe, but in the past two years of confrontation with the West, as Europe and America have joined ranks to pursue their policy of sanctions, the difference has significantly faded away.

Early in his tenure Putin has repeatedly referred to Russia as a European country. Putin told the BBC in March 2002 that “Russia is part of the European culture. And I cannot imagine my own country in isolation from Europe and what we often call the civilized world.” In 2005 he told Dutch journalists that Russians are Europeans “in their culture and mentality.” And on a visit to Britain in 2003 he said “Russia both geographically and mentally considers herself a part of Greater Europe…We believe that at the base of European identity is, first and foremost, culture and Russia without a shadow of a doubt belongs to this part of European culture.”

Yet at the same time there has always been a sense that, while being European – in terms of its history and culture, its Slavic language and its Christianity, Russia did not quite belong in the European world. It’s long become clear that Russia’s great power ambition and its gigantic territory make it impossible for her to become an EU candidate. And though it is by far the most powerful of all the post-Soviet states it lacks the soft power to become a center of attraction for its neighbors and fails to build partnerships elsewhere in Europe.. It is anxious to prove to itself and the world that, while it fails to catch up with Europe and the Western world in peaceful development, it is not inferior, but different. Hence the high popularity in Russia of the idea of a “Sonderweg”, a special path for Russia.

The problem is that we are not different enough to feel confident about our difference. Those sharing the notion of Russia’s special path find it hard, however, to define it in positive terms. But Russia does not seem ready to say point-blank that it is “not Europe” either. In spring of 2014 this statement – that Russia is not Europe – was included in the draft Foundations of the Russian Cultural Policy put together by the Russian ministry of culture. One month after its publication, however, the line “Russia is not Europe” had disappeared.

It is this uncertainty about Russia’s own “Europeanness” that leaves hope that Europe will not always be seen as the enemy, almost as hostile as the evil America. Even today the more urban and younger Russian constituencies take a more favourable view of Europe as a model of high quality of life, and a concentration of cultural and historical values. In the current environment of economic decline and acute confrontation with the West the Russian leadership draws on the conservative and anti-western majority, but Europe has not fully lost its attraction.

Even Vladimir Putin occasionally tends to get softer on Europe: When asked by Corriera della Sera in June 2015 whether Russia feels as an abandoned lover forsaken by Europe Putin responded: “We never treated Europe as a mistress… we always offered serious relationship.”

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.