What does Germany think about its role in Europe?

With Germany's pivotal role in Europe crystallising in the face of the EU's crises, an expert survey reveals how German policymakers feel about their partners

The three major crises of 2015 have all underlined Germany’s pivotal role in the European Union. Firstly, Berlin’s initiative with France over the war in eastern Ukraine meant that it was able to secure the German preference of a negotiated solution as opposed to arming fighters. Any escalation might have ruined the opportunity for EU consensus over sanctions against Russia, and could have lead to a weaker EU, a disintegrating Ukraine and a win for greater Russian nationalism. Secondly, in the bitter quarrels over a third financial package for Greece, Germany held its ground on structural reforms and additional funding. Without Berlin’s pressure to reach an agreement, the euro zone could easily have split or lost Greece. Finally, Germany’s decision to accept large numbers of refugees coming through southern member states prevented the imminent collapse of the EU’s migration scheme and forced a burden-sharing arrangement on the remaining member states. It is in this crisis that Germany’s seemingly towering role is shattered. Berlin has issued several strong calls for solidarity with little effect. Aside from the support given by governments in Stockholm and Vienna, Merkel stands rather alone as many other governments fail to move towards implementing the agreed relocation scheme for up to 160,000 refugees in the EU’s south.

None of these three crises have been solved as 2015 draws to a close, but each has been shaped by the choices and actions of German political leaders. Berlin’s leadership model has appeared to be rather unilateralist during these crises, along the lines of William Tell in Friedrich Schiller’s drama – “the strong is strongest when alone.” Angela Merkel and her government have also engaged more with other member states – for instance with France and Poland on Ukraine; with France, the Netherlands and the European Commission on the Greek issue; and with Italy, the European Commission and the countries along the Balkan route in the case of the refugee crisis. However, despite Germany’s enhanced engagement, the timing and the trajectory of initiatives has been set by Berlin.

Against this background, the German view of the EU and its partners is of great importance. What does the political class in Germany think about cooperation with other member states, and which of those states do the Germans want to interact with or feel the need to work with? How does the German policy elite see its own role compared to other large member states; and what is the German view on forming coalitions with others?

Answers to such questions are to be found in the results of an online elite survey ECFR conducted in June and July of 2015 that builds on an earlier assessment with participants from several member states. Amongst those who took part in the survey were government actors (mostly foreign ministries), member of other government agencies and parliaments, experts from think-tank communities in member states, and other professional observers of EU policy-making. All were asked about their views on interaction, influence and coalitions between member states in the EU.

In Germany, over 50 experts participated – the largest response rate in any of the EU member states, making the sample a highly reliable indicator of contemporary thought amongst the political class.

Who is the most influential EU member state?

Unsurprisingly, the dominant view of the German political class is that Germany is the most influential member state of the EU. The data collected in response to the question of which member state each government would generally contact first and/or most on EU affairs indicated that no other country is contacted more or with a higher priority than Germany.

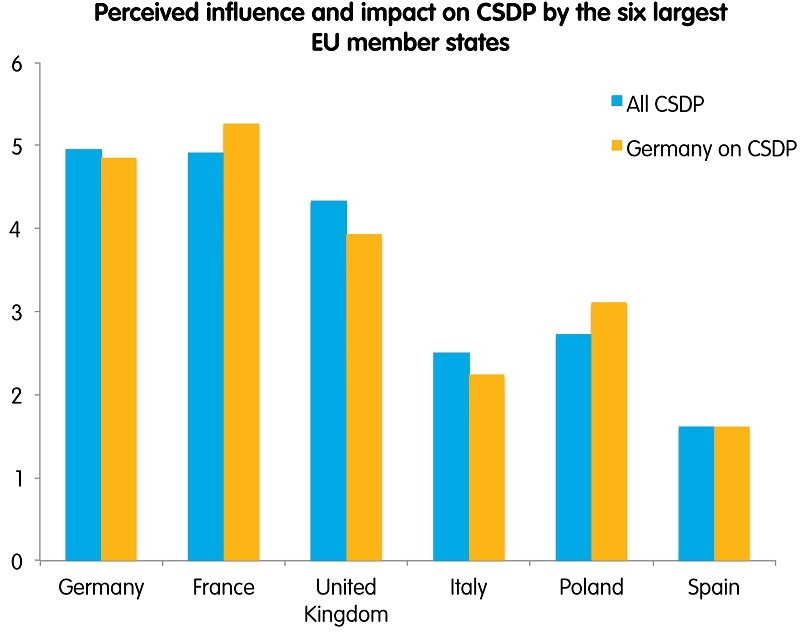

The Germans are in good company when it comes to the belief that they are the most influential member state. Data shows that this is not just the prevailing view in Germany, but also amongst the political elites across all EU member states. The German view of themselves is actually slightly self-critical. While most respondents ranked Germany first on foreign policy security and defence, the German participants in the panel put France on top in this regard. The graph below shows the ranking of the six largest member states in terms of their influence or impact on CSDP and differentiates the German responses from that of all other EU member states.

German respondents put the Netherlands first in their ranking of affluent smaller member states. Among the remaining member states, the three eurozone programme countries are seen to have had the biggest impact on EU policy over the past five years. Here too, the German sample does not differ significantly from the overall assessment incorporating all members.

A specific German-held view appears in the questions about preferences for patterns of interaction. When asked which member states generally share many of Germany’s interests and preferences on EU policies, the Berlin policy community puts the Netherlands ahead of all other member states, followed by Austria, France, Finland and Poland. This judgement is supported by the assessment of responsiveness. For this metric Germans placed countries in the same order, with Netherlands first, Austria in second and France in third place. However, the data is slightly different when it comes to thinking about which partner the German government would contact first. Here, France is placed far ahead of anyone else, followed by Poland and the United Kingdom. London comes out visibly stronger here than either The Hague or Rome.

Which are the EU’s most disappointing member states?

When asked which member states have disappointed partners the most in recent years, the German judgement focuses on the same three countries as all respondents – Greece, Hungary and the UK – but it is clearly more critical than other members. As the graph below indicates, the German political class is more consistent in its disappointment with Greece and Hungary than other member states, while the German judgement on the UK does not differ strongly from that of all respondents.

How do EU actors feel about coalitions?

Regarding coalitions between EU member states, the German view is more pronounced than the general assessment. Like most members of the EU’s political classes the Germans strongly expect to see more coalition building in future. 67 percent of German respondents (compared to 53 percent among all) believe consensus building among a group is essential for arriving at decisions with the 28 member states. They also see coalitions more clearly as a permanent but informal structure, whether those coalitions are issue specific or cross-cutting. The charts below show the German assessment compared to the general view.

The Germans much prefer the idea of economic and social union over any potential energy union (55 percent to 16 percent), but the results from other EU member states were rather different at 38 to 30 percent. 42 percent in the German political class see coalitions as desirable, even with several cores, whereas 29 percent do not. Most popular was the practice of building of coalitions without the emergence of a core. Should deeper integration be advanced by a core group, all respondents (68 percent) and the German sample (71 percent) agree that this core should focus on either economic or social union as a follow up to monetary union (within the euro zone) or on energy union (creating a single energy market with a single energy trade policy), but the preferences between states differ.

How should Germany react to these findings?

In conclusion, Germany’s leadership capacity is strong, and the data supports claims that Germany has a significant “following” among member states from all regions. Berlin itself seems to be most focused on France, Poland and the Netherlands. These countries would likely be cornerstones of any future coalition strategy, seeking to form a shapers’ group against the current trend of political fragmentation within the EU. They would hardly suffice alone, however, given the current political clout of France, or the coalition outlook of the new PiS-lead government in Poland.

To lead in the EU, Germany will have to invest more. Berlin will have to keep the EU together against the rise of significant anti-EU sentiment in several member states; it will need to engage in sectoral deepening, because the consensus over a single unchanging core is weak, and it should seek to engage other member states that are capable of acting. The group that should be focused on in this regard are the affluent smaller countries in the EU. They are geographically close to Germany, share many of the same preferences, and according to the data, they want to work with Berlin. Together, the Nordics, Benelux and Austria represent a strong part of the EU’s economy and its financial resources; the quality of governance in these countries is generally high, and the foreign policy outlook corresponds rather well with that of Germany.

Berlin will need to take the initiative to make their leadership a reality. Germany’s political class should understand the frustrations and hesitations in capitals across the EU. After all, to many, Berlin has not seemed to be in listening mode in recent years. The German political class may disagree, but actors would be surprised about the responsiveness they would find in Germany, if and when it begins to reach out more seriously and more consistently.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.