The unwavering European: Spain and its place in Europe

ECFR’s Coalition Explorer shows Spain to be an outlier in Europe – as it places great weight on foreign policy. But could new political turbulence thwart its ambitions once more?

Spanish politicians have always been proud of the consistent Europeanism of Spanish citizens. Indeed, until recently, no political party had ever played the Eurosceptic card. New on the scene now is insurgent far-right party Vox, which entered the Andalusian parliament in December and is polling at double digits for the next general election. But even it has avoided the Eurosceptic line of attack.

Regardless of their political differences, the Popular Party’s Mariano Rajoy (in government until June 2018) and the Socialist Pedro Sanchez (who became prime minister after winning a no confidence vote against Rajoy) agree that the European Union should be Spain’s main foreign policy priority. There is a broad consensus among Spanish political parties to aim for the levels of influence Spain enjoyed in the 1990s and to win favour as a committed partner in the EU, especially in the post-Brexit scenario. However, since at least 2010, Spanish academics, think-tank experts, and even political leaders have conceded that Madrid punches below its weight in Europe. Domestic problems lie behind this, from the ongoing effects of the economic recession, to the crisis with Catalonia, to the seemingly never-ending political instability brought about by successive election results.

Spain has long been a staunch supporter of the EU as a global actor – perhaps a legacy of Franco-era isolation

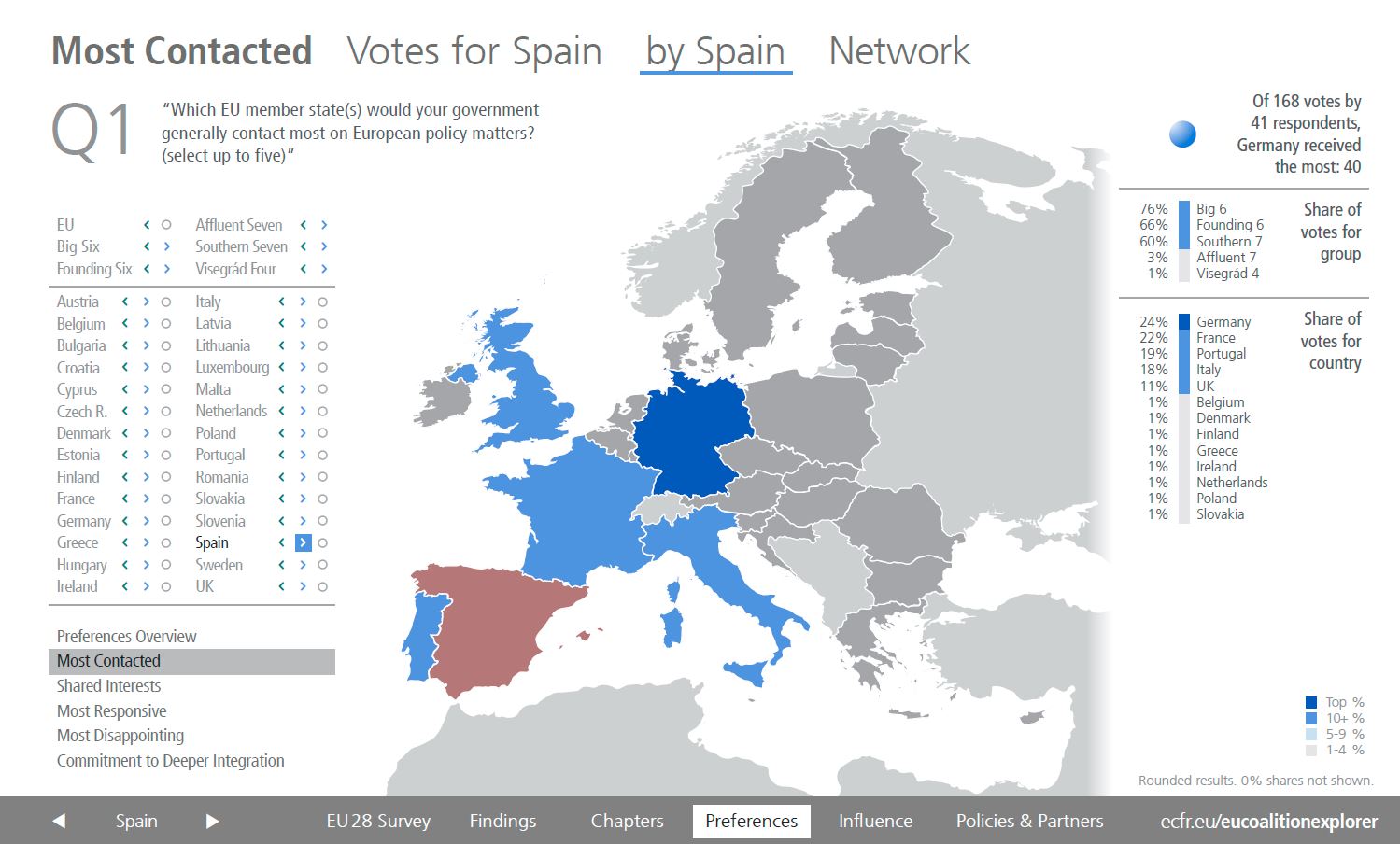

ECFR’s EU Coalition Explorer canvasses the opinions of those working in governments and think-tanks across Europe. It reveals that Spain is still more comfortable in what was known as the EU 12 (between 1986 and 1994) or even the EU 15 (between 1995 and 2004) than in the current EU since the enlargement eastward. Spain’s natural network of partners are the Southern Seven (Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, and Spain) and the Big Six (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland, and the United Kingdom). Evidence suggests it lacks close links with the Affluent Seven (Austria, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) and the eastern member states. It is as though Spain, from its leaders to its voters, have barely moved on from the days of the European Community when the club lavished attention and affection on the then new Iberian member states.

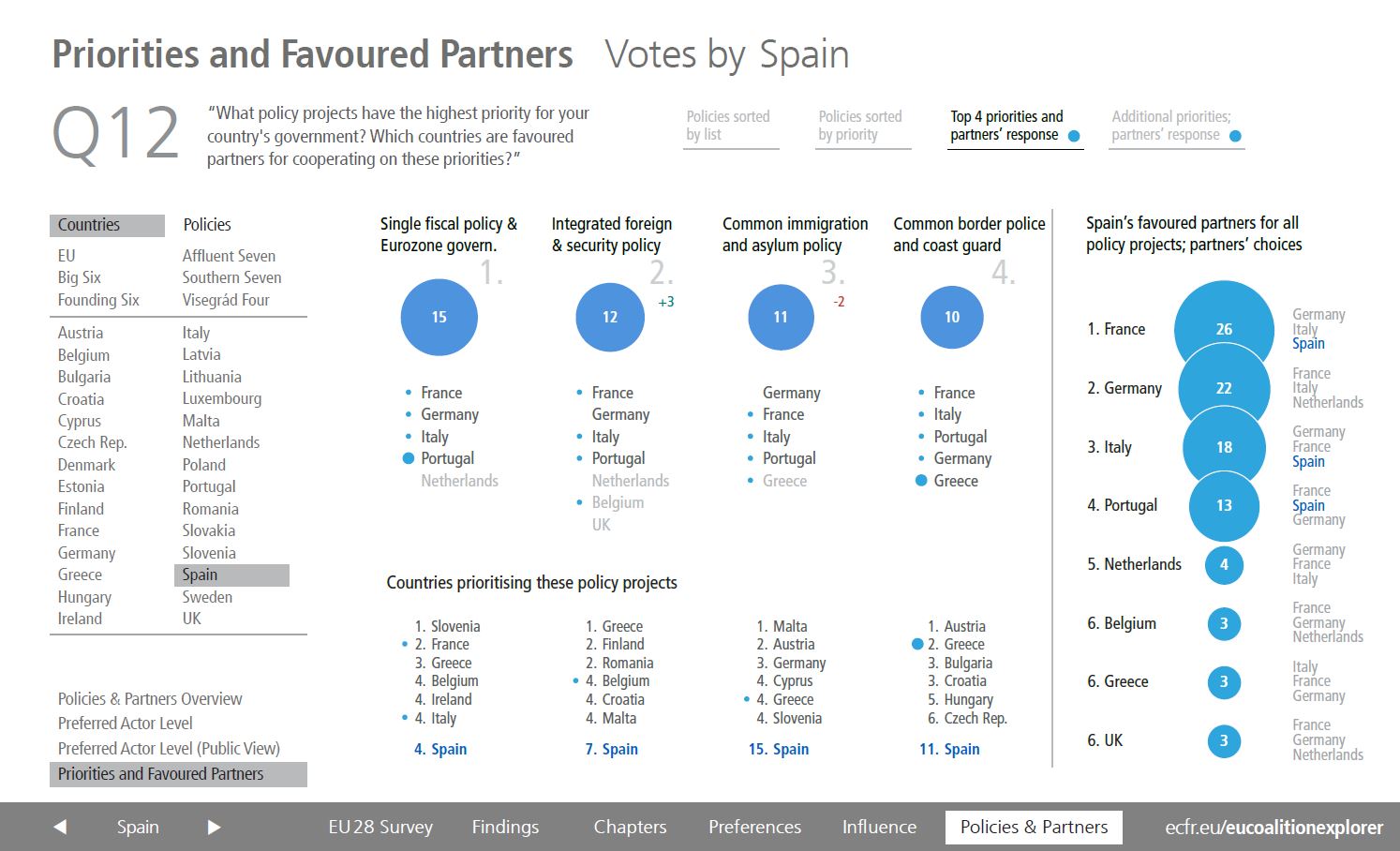

The Coalition Explorer study also shows that, unsurprisingly, Spain’s most favoured partners are France, Germany, Italy, and Portugal for almost all the political priorities in the EU. With these partners, Spain completes two different triangles of friends. On the one hand, there is the southern triangle with France and Portugal, very well defined by Christoph Klavehn in a previous ECFR commentary. Despite the broad cooperation agenda of this trilateral grouping, the larger two member states consider Portugal something of a junior partner, showing a ‘2+1’ pattern. Spain has less interest in working with Portugal than vice versa, even though it admits that it counts on its western neighbour for all European policy areas, from the common energy policy to common policy on justice and home affairs (mainly on countering terrorism and preventing radicalisation). A quite symmetrical situation obtains between France and Spain, with Spain in the role of the junior partner.

On the other hand, Spain’s preferred triangle is the second one: with France and Germany. For Madrid, Berlin and Paris have always been the capitals it looks up to, and it has actively sought their acceptance as a third leg of the Franco-German axis. There are nevertheless plenty of caveats about Spanish aspirations. For France, Spain is only the third favoured partner (after Germany and Italy), and it is only in fifth place for Germany (after France, Italy, and the Netherlands – and actually level pegging with Poland). Spain may be closer to France in terms of policy priorities, thanks to their shared neighbourhood and Mediterranean interests, but Spanish public opinion recognises Germany as the most important key partner, according to a report from Real Instituto Elcano.

In relation to Italy, ECFR’s Almut Möller is certainly correct to observe that contacts between Madrid and Rome are frequent: they share common interests such as eurozone governance and the common immigration and asylum policy, and they find each other relatively easy to work with. Nevertheless, Italy’s growing Eurosceptic and enfant terrible behaviour has made Spain more reluctant to cooperate with it, not least given its yearning for approbation. In addition, Spain is on occasion tempted to see Italy’s malaise as an opportunity to overtake its fourth position in the ranking of the most influential EU member states.

As far as Spain’s top three policy priorities are concerned, what is surprising is that foreign and security policies are its second most important priority. This makes it quite an outlier when compared with other member states. It is unusual for member states to place progress in foreign and security affairs ahead of immigration and asylum, energy, or a common border and coast guard. That said, Spain has traditionally been a staunch supporter of strengthening the EU as a global actor, perhaps out of a desire to overcome the isolation syndrome born from the very real isolation of Spain during the Franco regime.

The arrival of Sanchez as the Spanish representative at the European Council raised high expectations in many European capitals. The new prime minister quickly embraced Emmanuel Macron’s idea of the “Europe that protects” as a way to reassert Spain’s Europeanism. In a speech to the European Parliament in January 2019 he adopted an even more proactive stance, proposing to forge an environmental union and complete the foundations of the economic, social, and political union. This was a first step for Spain moving from words to deeds and starting to think bigger. Britain’s EU exit and Italy’s troubles could provide an opportunity for such hopes, as Spain can now realistically aspire to move from being just the fifth largest member state to becoming a necessary ally in safeguarding European integration. However, political turbulence before and after the general election to be held later this month could still prevent Spain from playing a greater role in the EU – yet again.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. Several hundred respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualisation, the EU Coalition Explorer, are available online at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU that is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

Laia Mestres is a research fellow associated to the European Foreign Policy Observatory at the Institut Barcelona d'Estudis Internacionals.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.