Five lessons from the local elections in Ukraine

What do Ukraine's local elections tell us about the country's political future?

Turnout was low, but respectable

The official participation rate for Ukraine’s local elections was 46.5 percent. This may sound low, but wasn’t much lower than the turnout for the parliamentary elections last October, which was 52.4 percent, and for the presidential election in May, which 59.5 percent. And these were local elections after all.

The real danger in these elections was not low turnout across the board, but rather differential turnout – i.e. a significantly lower turnout in eastern and southern Ukraine. In the 2014 presidential election, turnout in the western city of Lviv was 78.2 percent, while in the eastern Kharkiv it was 47.9 percent and in war-torn Donetsk it was only 15.1 percent. In the October parliamentary elections, Lviv managed 70 percent, Kharkiv 45.3 percent and Donetsk 32.4 percent.

This time round, turnout was 56.3 percent in Lviv, 44.4 percent in Kharkiv and 31.7 percent in Donetsk – lower in the east, but not by as much. Most probably, turnout was kept at a low level because of general discontent with the progress of reform and the state of the economy, rather than by an ominous existential gulf between engaged voters in the west and alienated ones in the east.

Turnout in Donetsk region was also negatively affected by the failure to hold a proper vote in the besieged port city of Mariupol and further north in Krasonarmiisk – after governor Pavlo Zhebrivsky campaigned against the vote, which seemed likely to favour candidates backed by oligarch Renat Akhmetov.

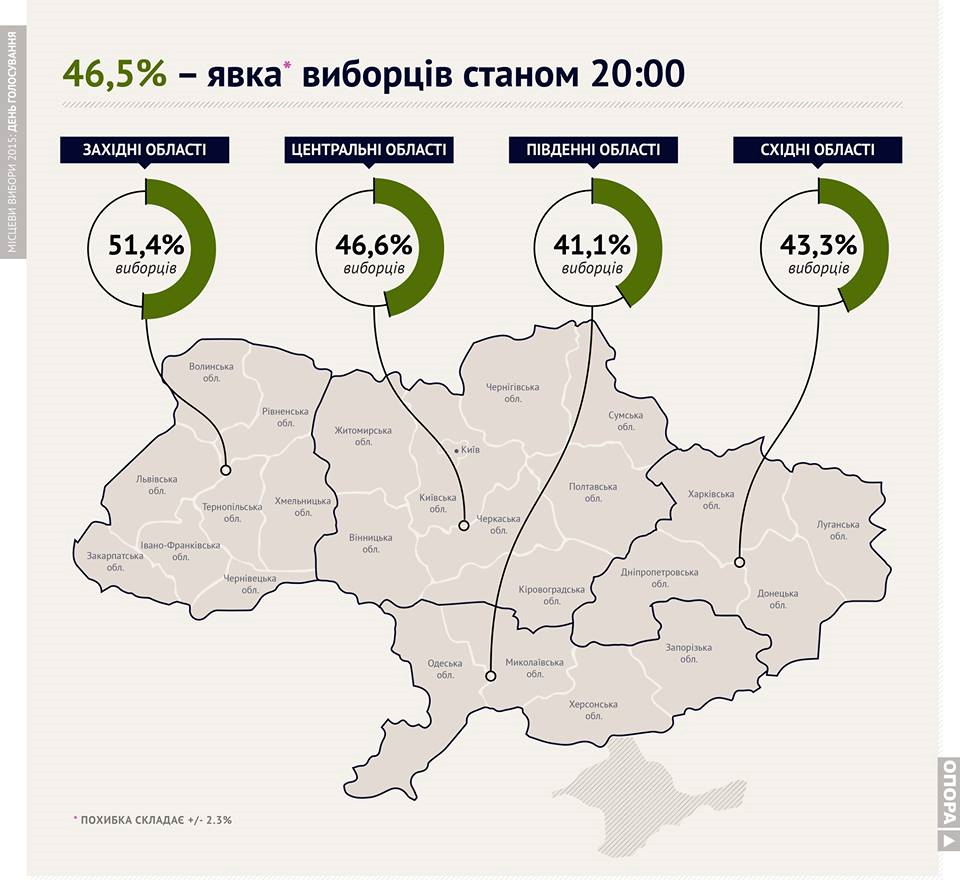

The image below shows turnout across the country in four macro-regions: 51.4 percent in western oblasts, 46.6 percent in the centre, 41.1 percent in the south and 43.3 percent in the east (source: Opora).

The governing party is accumulating power, but it’s not that popular

The two main parties that made up the backbone of the governing coalition formed last December were the Poroshenko Block and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatseniuk’s People’s Front. The latter is now so unpopular – polling less than 2 percent – that it decided not to stand. It largely folded into the Poroshenko Block, aka the Solidarity party, for these elections. The President’s Block has also absorbed the old UDAR party, the only remnant of which is in Kyiv, where UDAR leader Vitaliy Klitschko is on course to be re-elected mayor after winning an estimated 40 percent of the vote in the first round, despite remaining a largely symbolic figure. On the Kyiv City Council, the main party is Solidarity, not UDAR.

Exit Poll for the Kyiv City Council, estimated percentage of the vote

| Solidarity | 28.3 |

| Self-Help | 10.3 |

| Fatherland | 10.1 |

| Freedom | 9.7 |

| Unity | 8.5 |

| Party of Decisive Citizens | 4.8 |

| Opposition Block | 3.8 |

| Democratic Alliance | 3.7 |

| Movement for Reforms | 3.2 |

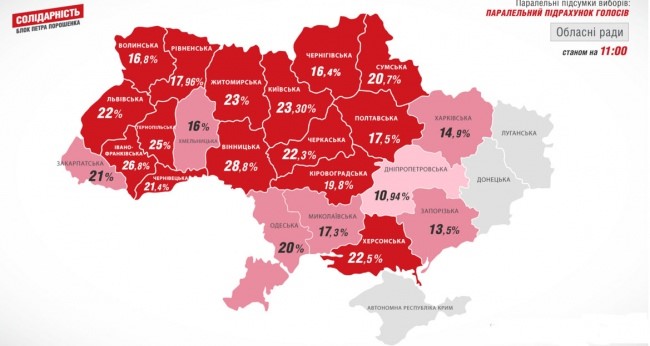

Solidarity led the vote in 15 out of Ukraine’s 26 voting regions, and the map below is in Ukrainian, but shows Solidarity’s wins across the country. Regions in which Solidarity came first are shaded red and the regions where they came second are shaded pink (from solydarnist.org).

Solidarity leads by default in small-town Ukraine; but apart from Kyiv it was not on course to win any of Ukraine’s other major cities. Solidarity candidates are through to the second round of elections in ten cities: Chernihiv, Poltava, Zaporizhzhia, Lutsk, Zhytomyr, Ivano-Frankivsk and Kirovohrad, plus possibly Odesa (see below). But of these, only Zaporizhzhia and Odesa were really big targets, but ultimate victory in either was unlikely – in Odesa the sitting mayor attempted to declare that he won a 52.9 percent victory in the first round (but what will happen there remains to be seen).

Solidarity owes its strong results to old-style deals with oligarchs and local power-brokers and the use of old-style “political technology”. The Presidential Administration covertly backed new clone parties against its main opponents. Nash Krai (Our Land) was developed explicitly to run against the Opposition Block – and was made up of local bosses in areas of the east and south adjacent to troublesome areas like the Donbas. Serhiy Kaplin’s new Party of Simple People was designed to take votes off Oleh Liashko’s Radical Party, and Dmytro Dobrodomov’s Party of People’s Control was supposed to do the same job of taking votes from Self-Help. The presidential administration has also been planning a left-wing party led by Vasyl Volha to blunt any revival by the populist left.

These smaller parties were basically 'flies' – and any bite they took out of the opposition vote justified their budget. Of these parties only Nash Krai emerged as a significant force, with its local political machinery providing victory in Chernihiv and a relatively significant number of votes in Kirovohrad (16.5 percent) and Zaporizhzhia (7.5 percent).

The deals that seem to have been made in order to facilitate the political survival of elites that outlasted Yanukovych in key eastern and southern regions were equally cynical. In Kharkiv, Mayor Hennadiy Kernes seems to have been allowed a free run in return for agreeing not to run as part of the Opposition Block (the outstanding legal cases against him may have helped him make up his mind). Kyiv didn’t put any strong candidates up against Kernes.

The situation with Ihor Kolomoisky, the well-known oligarch of Dnipropetrovsk, was more complex. A real fight in his home town will continue into round two. Kolomoisky’s candidate for mayor is his right-hand man, Borys Filatov, running against the unholy alliance of the Opposition Block and Poroshenko’s administrative resources, whose candidate was the notorious Oleksandr Vilkul, the man widely accused of organising the beating of local demonstrators during the Revolution of Dignity.

Despite this, candidates backed by Kolomoisky were expected to win in the key cities of Odesa and Kharkiv. In Odesa, Kolomoisky has longstanding business relations with current mayor Hennadiy Trukhanov, and a developing feud with anti-corruption governor Mikheil Saakashvili. In Kharkiv, Kernes made a tactical alliance with Kolomoisky at the last minute. It is hard to see whether Kyiv is happy or concerned about the possibility of Kolomoisky’s power being on the rise once again. Part of the calculation may have been that Kyiv was so desperate to defeat the Opposition Block (apart from in Dnipropetrovsk) that it gave Kolomoisky a free hand to use his two ideologically-opposite satellite parties, the nationalist Ukrop and the Russian-speaking Renaissance party to win votes in the east and south. Renaissance did better, and is now the largest single group on the Kharkiv council (Renaissance has 50 seats, Poroshenko 24, Opposition Block 22, Nash Krai 13 and Self-Help 11). Ukrop did less well, and its best performance was actually in Volyn (35 percent), which is home to a strong veterans’ movement.

The Opposition Block does well, but faces a split

Much of the initial reporting on the elections used the classic trope of a Ukraine-still-divided-between-west-and-east. The pro-Russian Opposition Block did indeed lead in six regions in the east and south shown in the map below in dark blue (Donetsk and Luhansk, plus Zaporizhzhia and Dnipropetrovsk – see below, Mykolaiv and Odesa), with three second places in Kharkiv, Kirovohrad and Kherson oblasts shown in cobalt blue. Light blue shows respectable third places in central Ukraine (this is the Opposition Block’s own map, from opposition.org.ua).

However, this map is misleading. The Opposition Block was hoping for break-away wins in the Donbas. But, as stated above, local elites were busy making deals with Kyiv. In Odesa, Trukhanov cultivated pro-Russian voters, but at a respectable distance, and also faced off a challenge from the more hard-line Serhiy Kivalov. In Kharkiv, Kernes seems to have quarrelled with real pro-Russian hardliners, like Mikhail Dobkin, though remains eminently biddable. But all eyes are on the close second round race in Dnipropetrovsk, which is the one regional council where the Opposition Block was predicted to win first place, with 30.5 percent against 25 percent for Kolomoisky’s Ukrop. In Zaporizhhia the leading candidate was Volodymyr Buriak, backed by Renat Akhmetov.

The Opposition Block is also due to split in two after the elections. Serhiy Lovochkin is expected to rebrand his half of the party as the “Party of Peace and Development”. Borys Kolesnikov and Renat Akhmetov will be left as curators of the rest.

Tymoshenko down, Freedom Party up

Yuliya Tymoshenko has recently been enjoying a mini-revival in the opinion polls. Her party is nominally part of the governing coalition, but she has been actively campaigning against tariff reforms. In a KIIS poll in September 2015, she was near to catching up with the Poroshenko Block and Solidarity, with 18.8 percent to their 19.9 percent. But Tymoshenko’s popularity is largely based on TV populism. This campaign was not an ideal fit, as she lacks a coalition of local city machines (oligarchic backers, simple manpower). Her party therefore won a disappointing 10 percent in Kyiv and failed to win first place in any of the regions – though her party traditionally scores well in rural and small-town Ukraine, where results have yet to be fully counted.

On the nationalist flank, the Right Sector wasn’t standing in the elections, Ukrop was largely confined to east-central Ukraine, and the populist Radical Party of Oleh Liashko now has many competitors, including Tymoshenko and the Party of Simple People. So one slight surprise from the elections was the apparent mini-revival of the nationalist Freedom Party, which seems to have been due to right-wing voters having less choice. The Freedom Party missed out in the parliamentary elections held in October 2014, with only 4.7 percent of the vote. This time, it won 31.4 percent in Ivano-Frankivsk, 13 percent in Poltava and 9.7 percent in Kyiv.

More reform or more populism?

The Brownian motion of Ukrainian politics means there are too many new forces in Ukraine. But few of them are anything but phantom parties. Self-Help won in Lviv (32 percent), and also did well in Kyiv (10.3 percent); though arguably its respectable performance in parts of the east and south was far more significant – 11.8 percent in Kharkiv and 12 percent in Mykolaiv. But, given the (corrupt) cost of politics in Ukraine, there are few new “activist parties”, with the notable exception of parties such as the Democratic Alliance in Kyiv. Saakashvili’s ally Sasha Borovik did surprisingly well in Odesa with around 25 percent, which may embolden others in Kyiv to press ahead with reform. But most new parties are just “political technology” projects.

With politics in flux, almost everybody, except for Yatseniuk, is likely to campaign for early parliamentary elections, possibly in the spring. President Poroshenko talked about a new round of reforms after these local elections, but the opposite is just as likely. The governing majority could be reformatted, but it if the priority is to push through the constitutional vote on the Minsk process (which needs 300 votes) and consolidate ties with the east and south, then anti-reform forces may only end up stronger.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.