5 graphs that explain EU foreign policy making in 2017

There remains a core agreement on certain key values but the EU is deeply divided on immigration, on Russia, and perhaps soon on the United States.

After years of flesh wounds, it feels as if the crises that have hit the EU in 2016 might now lead to catastrophic blood loss. The establishment unexpectedly lost in the Brexit referendum and the American elections; energetic centrist Matteo Renzi resigned as prime minister after losing a referendum in Italy; elections and primaries in Austria and France showed growing divisions in society; and in Hungary and Poland, increasingly illiberal governments are at odds with the European Commission.

As we are heading towards another year of elections in France, the Netherlands and Germany, there is no doubt that national political changes will directly influence EU decision making. For 2017, it is not enough to look at government statements to predict foreign policy positions. Instead, we need to examine the coalitions and divisions that exist both within and between countries and which will play a key role in determining policy.

To this end, ECFR has conducted a survey in all 28 member states, asking representatives of 74 parties about their foreign policy priorities in the post-Brexit vote landscape. The results show a political class with similar concerns, but different emphases that may lead to conflict. Nonetheless, there are still strong common grounds for EU leaders to build on in the coming year.

1. An open and Western-oriented consensus still exists, despite recent election results;

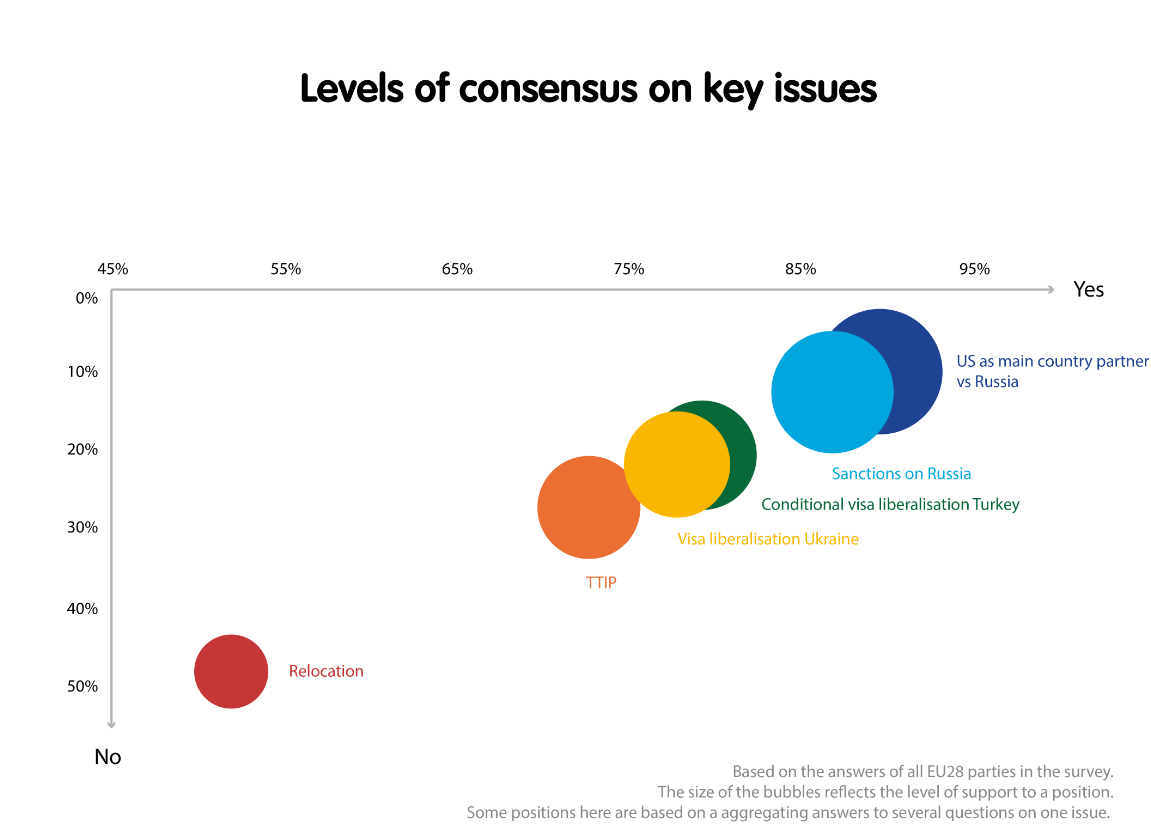

Unanimity is as always lacking but there remains a substantial consensus on many traditional EU values: a strong transatlantic relationship, openness to neighbouring countries, and an interest in global trade. The outlier is the issue of refugee relocation, where there significant disagreements exist.

The EU programme for relocation aims to relocate over 100,000 refugees from Italy and Greece to other EU member states. A small majority felt that accepting relocation should be mandatory for all member states, but a significant minority (36%) felt that opt-outs should be allowed if the state in question contributed to solving the refugee crisis in other ways.

2. but a growing number of insurgent parties have different foreign policy priorities compared to traditional parties

As discussed in our report ‘The world according to Europe’s insurgent parties’, a group of old and new parties challenging the establishment have slowly been gaining traction for years.

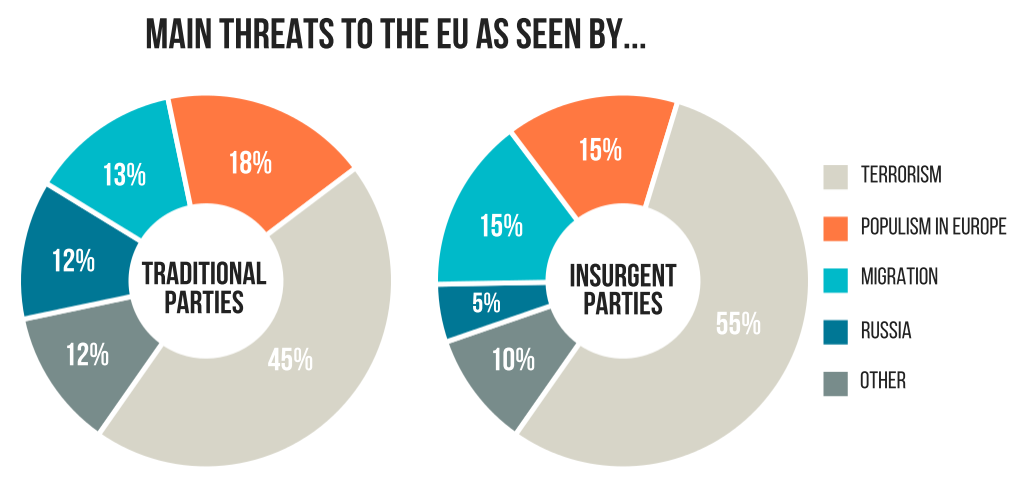

Looking at their views towards the major challenges facing the EU, there at first appears to be a large degree of consensus, with both traditional and insurgent parties placing greatest emphasis on the threat of terrorism.

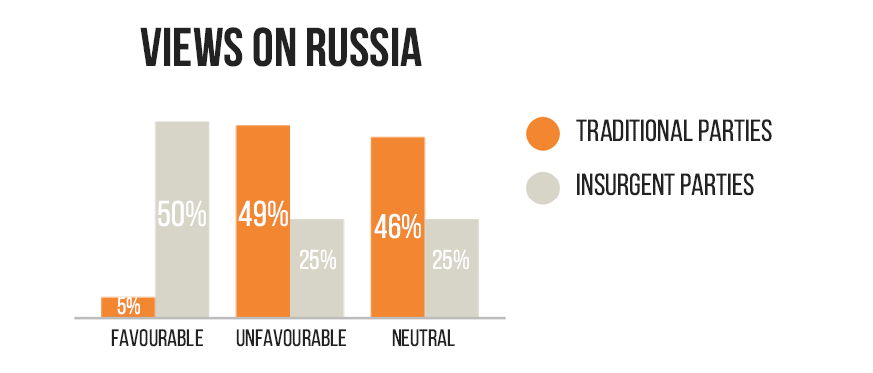

However, there is clearly a divergence when it comes to views of Russia (below), with insurgents much more inclined than traditional parties to seek an accommodation with Moscow. In 2017, with the potential rise of Front National in France and FPÖ in Austria, this could lead to a significant change in EU policy towards Russia, particularly on sanctions.

3. The nature of the EU’s favourite partner has changed dramatically

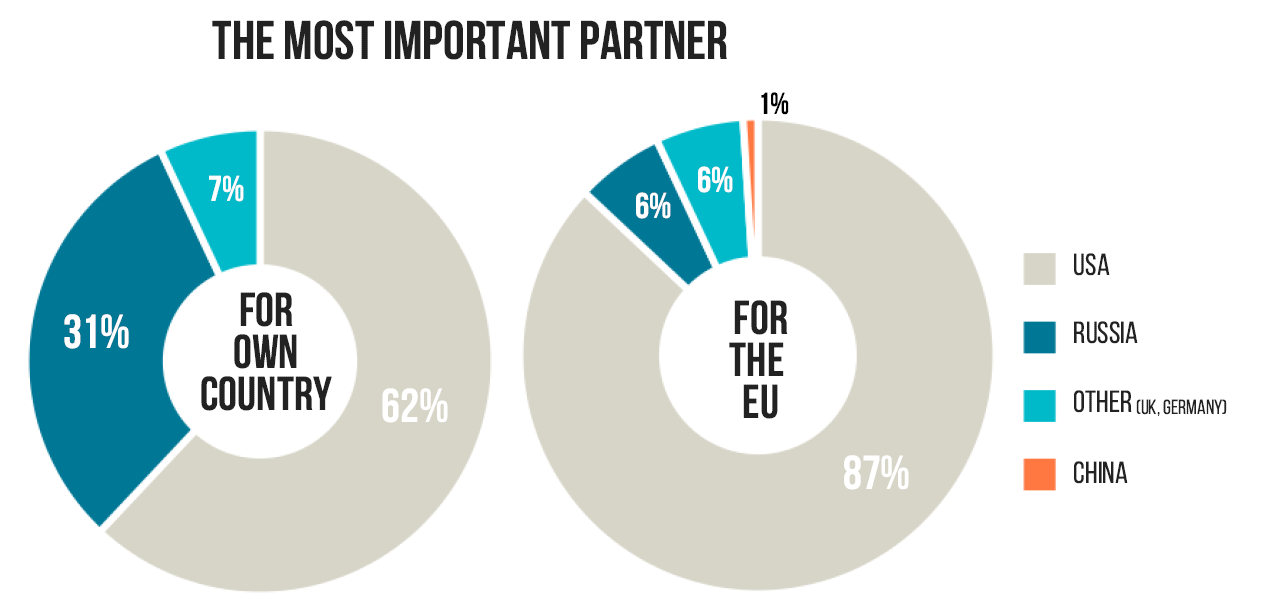

The US is still seen as the most important international partner – in both foreign policy and economics – for member states and the EU as a whole. But while this may not have changed, the nature of that partner certainly has. Trump has spoken positively about Russia, a country seen as a security threat in much of Europe; he has questioned transatlantic and NATO alliances; and he supported Brexit, one of the greatest blows to the European project.

There is a therefore a worry that member states prioritising their relationship with the US may end up adopting policies at odds with the interests of Europe as a whole.

4. And support for European security cooperation is weak

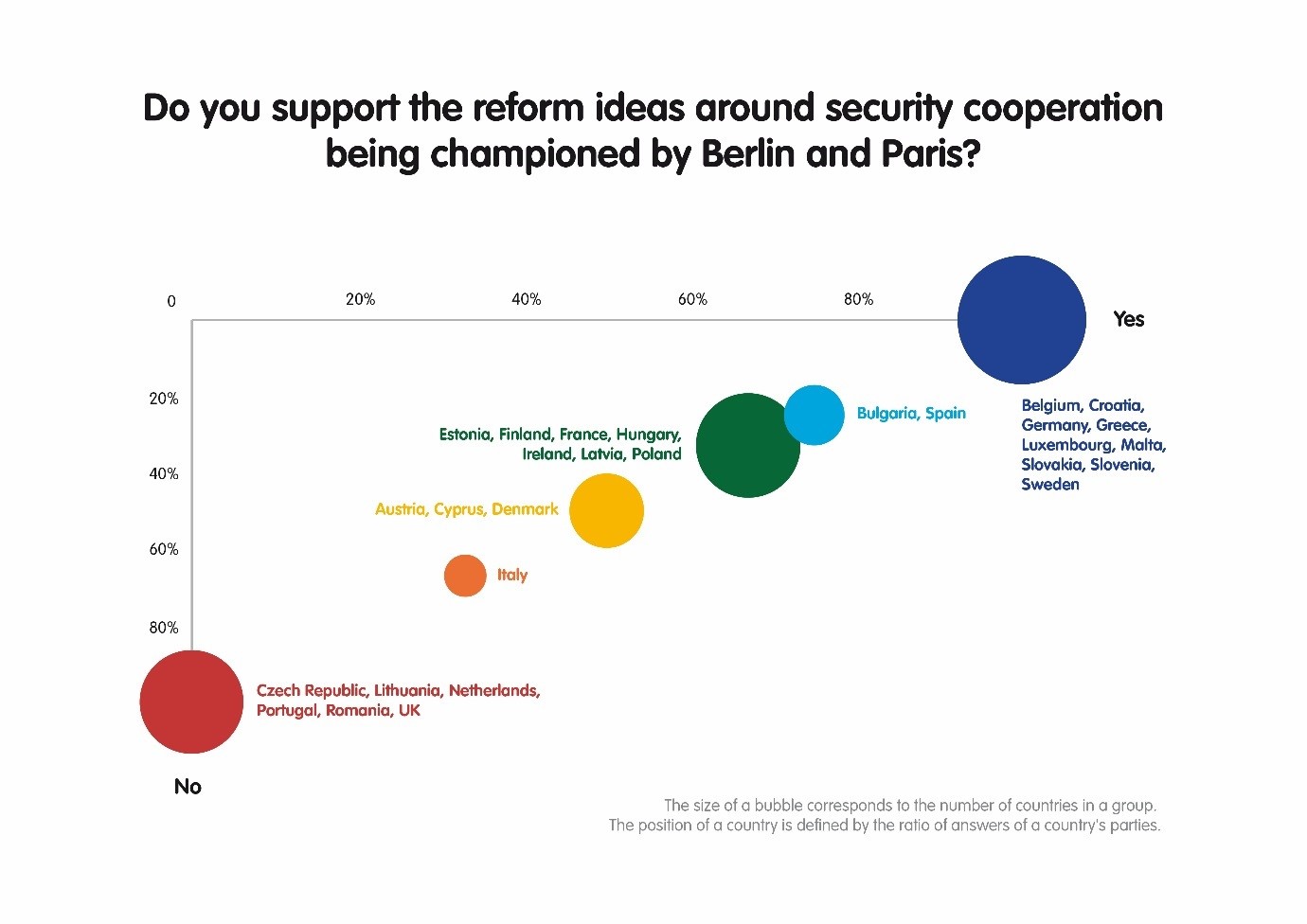

A French-German paper published after the Brexit referendum called for a new security compact for Europe, including changes to the common European asylum and migration policy. This debate on security cooperation is ongoing, and during the December European Council, heads of states agreed to increase cooperation on European defence and allocate more resources. However, we found that within most countries, there is no consensus on this increased security integration, and in seven countries the parties discussed leant towards a rejection of these ideas.

Will 2017 be any better?

Promoters of the European project would like to spend 2017 licking their wounds and coming up with new projects that that will re-ignite the integrationist passions of years past. Of course, the world is unlikely to stop and allow the EU to get off. But the more fundamental problem may be that little consensus remains for such new projects of integration. Yes, there remains a core agreement on certain key values within the EU, but the EU is deeply divided on immigration, on Russia, and perhaps soon on the United States. Even the most widely-touted next project, security cooperation, commands very little consensus among European political parties. Overall, if the EU wants to stanch the bleeding, it will need to concentrate more on finding areas of cooperation that appeal to national political parties, including insurgent parties. Our initial research indicates that a good place to start might be more visible cooperation on counterterrorism.

The survey was conducted as part of the Rethink: Europe project by ECFR’s network of Associate Researchers. Learn more about the network here.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.