Band of brothers: Why like-minded powers need to hold the line on China

Like-minded countries are starting to protect themselves from US unpredictability and Chinese dominance by forging new coalitions. This will only work if they limit their solo deals with Beijing

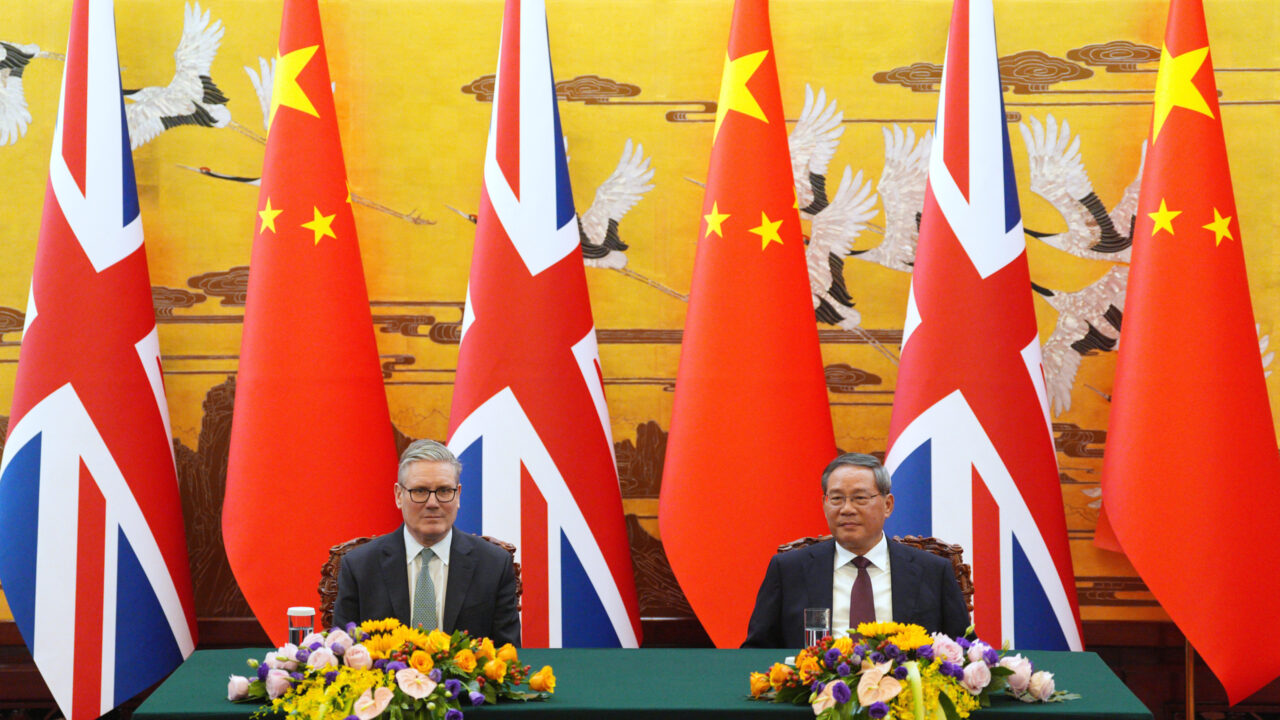

A new pattern of defiance is emerging in the world against US president Donald Trump’s disruptive policies. This week, a British prime minister is visiting China for the first time in eight years, and the EU and India finalised a landmark trade deal—20 years in the making but accelerated by the two sides’ tensions with both the United States and China. The Canadian prime minister, Mark Carney, also visited Beijing earlier this month and heralded China as a place of “enormous opportunities” in his search for diversification. He made the case for this wave of hedging in Davos last week when he argued that without visible resistance, a soft approach to Trump only feeds his ambitions.

These dynamics are framed as part of a new “pragmatism”, where countries spread their bets and build stronger links with others to protect themselves and have more choices in a volatile world. The approach will fail, however, if this pragmatism involves backsliding into opportunistic deals with Beijing. European leaders have a chance to fortify their countries, but this will require conscious restraint from short-term and short-sighted rapprochement with China. Such deals will fracture coalitions rather than shore up their resilience.

Cumulative damage

The direction of travel for Britain and Canada toward China should not be exaggerated. These are still modest adjustments rather than a “golden era” style opening of sensitive sectors. But the cumulative toll of a China-related “pragmatism”—that involves only low-grade economic compromises—undermines collective efforts and is profoundly destructive to building a resilient coalition of like-minded powers.

This is not always obvious at the level of individual decisions. Letting Chinese wind producers win procurement contracts, failing to put tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, accepting low-grade, final-assembly-style Chinese automotive investments, or softening cyber rules to allow a Chinese presence in sensitive infrastructure can all look like “pragmatic” choices in isolation. When spread across a range of major economies, however, they preclude maintaining market scale for non-Chinese alternatives.

The effect is to allow China to race unimpeded toward monopolistic domination of a wide range of economic sectors. Already, China’s export surpluses are causing a deindustrialisation-level shock across advanced economies and are squeezing the traditional development pathway for many emerging economies. This has security ramifications: it hollows out crucial industrial capacities and augments China’s coercive power. It also has political implications: the geographic concentration and speed of the impact in traditional European industrial heartlands bolsters the rise of extremist parties.

The deal China offers Europe and other rich economies is simple: hand over your high-tech industries through technology sharing, and we will buy your farm goods, seafood, minerals and a diminishing sprinkling of luxury goods. For developing countries, it’s: sell us your raw materials and give up on building your own factories—unless they are so deeply embedded with China’s as to be virtually indistinguishable. The Chinese leadership is clear about its priorities and not shy in warning policymakers: try to stop us, and we can make things worse for you, faster.

Given the state of the Chinese economy and Beijing’s ongoing push to favour domestic producers, the rewards from opportunistic deals with China are now painfully low anyway compared with the collective risks if this trajectory continues. The era of economic complementarity, rapid growth and “great opportunities in the Chinese market” is already over.

With America’s foreign policy so volatile and China’s dominance looming, like-minded countries must align their economic defences. Getting this right requires restraint in solo deals and a more ambitious level of joint action to address the shared risks of a China-dominated economic landscape.

Getting coalition building right

The India-EU trade deal this week proves that a like-minded approach to China can provide economic and strategic payoffs.

There is good reason to believe that the EU is not set to succumb to the China temptation. The past year has reinforced the sense that if European countries act as a squabbling group of opportunistic small and middle powers, big predators like China will pick them off one by one. EU policymakers are applying this lesson to a broader group. The India-EU trade deal this week is the best embodiment of the kind of “pragmatism” the moment really requires—a deal that would not have been concluded like this in a different era, given that both sides were previously rigid in their negotiating positions—and proves that a like-minded approach to China can provide economic and strategic payoffs.

Europe and India are formidable powers: the EU is the second-largest economy in the world, India is the fourth and rising fast. Together, they have scale, talent and capital. The potential for collaboration on clean tech, AI, defence-industry and advanced manufacturing is enormous. Without India and Europe, other countries will find it difficult to build alternative supply chains in key sectors—from semiconductors to wind turbines, from drones to software development. Their shared concern about China creates drastically more space for each other in their respective markets and technology ecosystems than if both sides had decided that the pragmatic choice was just to resign themselves to dependency on China.

Europe’s own approach to China is now on the verge of another step-change. Policymakers increasingly see the danger of China wiping out factories and have little appetite to accept the deindustrialised fate of the UK and other services-centric economies. The EU is preparing to put in place measures that offer the chance to set the bloc’s overall China policy framework on a far more robust footing, such as tougher cyber-security rules for key sectors and China-focused European preference rules. Policymakers in Europe also increasingly appreciate that pragmatism with China policy cannot mean inaction and delay, with an estimated five hundred manufacturing jobs in Europe being lost every day that can be directly attributed to China.

In the coming weeks, a key test will be whether member state leaders succumb to desperate wishful thinking again about what kind of deals they can strike with Beijing or the urge to put addressing China on the back burner yet again, at a time when the transatlantic relationship is so freshly strained over Greenland.

The deadly lure of opportunism

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz has so far taken a different approach from the British and Canadian premiers, and is unlikely to show up in Beijing proclaiming a new strategic partnership. He deliberately went to India first and has been clearer than any of his predecessors about the need to de-risk from China. But the temptation to also try to get a quick win in China for his visit in late February will loom large.

The onus will still be on Brussels to push partners to act together, strengthen their own defences and avoid steps that weaken the economic security of a wider like-minded group. Fast-tracking the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with India and the EU’s nascent coordination efforts with the Trans-Pacific bloc of countries are steps in the direction of the right kind of pragmatism: mutually agreed standards that form the core of an interoperable approach to economic security, informal agreements to manage overcapacities, and the consistent application of rules on sensitive technologies. The EU-India agreement could be a foundational part of a new era of global economic cooperation—a collective vaccination against the allure of easy gains in China. But this protection could easily be chipped away if the like-minded partners give in to deadly opportunism that leaves a China-sized hole in their shield.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.