One battle after another: Factional struggles and the making of Trump’s foreign policy

Summary

- Donald Trump prioritises headline-grabbing “wins” over the detail and substance of foreign policy.

- His administration has dismantled the interagency process that once filtered and vetted the policy options that reached the president, replacing it with a factional one.

- In the style of court politics, the factions in the White House compete to convince Trump their preferred option will serve him up the biggest win.

- The fierce competition means the administration’s defence and security policy is not informed by any previously defined strategy, but is in a continuous state of renegotiation.

- Influencing the Trump administration requires understanding that it does not make decisions like previous US administrations. Europeans can influence the factional process, but only if they can correctly perceive the factions.

Participation prize

“Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize for having stopped 8 Wars PLUS, I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace … ” (Donald Trump, letter to Norwegian prime minister, January 2026)

It seems winning the inaugural FIFA peace prize was not enough for Donald Trump. Having kicked off this world cup year with a regime decapitation in Venezuela, the US president swiftly refocused on his old goal to “acquire” Greenland. He also found the time to threaten Iran’s leaders with the “Maduro treatment”, and he did not spare America’s world cup co-hosts either: Canada was treated to tariff threats and Mexico those of the military variety. In early February, the boss of global football’s governing body, Gianni Infantino, was asked whether, in hindsight, his peace prize might not have gone to the right person. His response was, “objectively, he deserves it.”

January left European leaders reeling. They had spent the first year of Trump’s second term belatedly coming to terms with the prospect of “defending Europe with less America”. Now, they were confronted with an imperialist US and the possibility of defending Europe against America. The days of Trump’s campaign promises to put “America First” with a “president of peace” at the helm seem like a lifetime ago. The purging and sidelining of the traditional Republican foreign policy hawks (“primacists”) from the second term cabinet does not seem to have had much impact on its ideological direction. “Restrainers”, who want US policy to focus on the homeland, have not prevailed in their stead; nor have “prioritisers”, who think the focus should be the Indo-Pacific. The much-delayed publication of America’s national security strategy in December and national defence strategy in January only added to the confusion.

Even officials close to Trump have struggled to decipher the direction of travel. What the president says and what he does often deviate from and sometimes contradict the statements of his cabinet members. At the Shangri-La Dialogue in May, secretary of war Pete Hegseth proclaimed America would shift political attention and resources to the Indo-Pacific, meaning Europe must take greater responsibility for its own security. Then in September, Trump announced the US would keep troops in Europe and maybe even add more. The president also authorised strikes on Iran’s Fordow nuclear facilities, despite his director of the Office for National Intelligence, Tulsi Gabbard, stating Iran was not seeking to build a nuclear weapon.

The president’s unpredictability often seems to be the only constant. But that alone does not explain the strategic cacophony of US defence and security policy over the past year. This paper argues the administration’s policy is the product of a president fixated on short-term “wins” and factional competition in the White House. The factions diverge on the scope of US military engagement and America’s role in Europe, yet converge on method: they all push their preferred outcomes by appealing to Trump’s need for visible victories, lucrative deals and shows of strength. The result is a fluid, personalised foreign policy process, in which ideology and strategy are subordinate to Trump and his wins.

The case studies in this paper show how the game has played out so far in: the western hemisphere, Iran and Israel, China and Taiwan, and Russia and Ukraine. The paper then explains the implications of this for America’s global power and for Europe. US attention and resources are stretched, but all the factions seem to agree that Europe is less ally and more prey. Whatever number of American troops end up staying in Europe, they no longer belong to an ally that defines “the West” as a coalition of liberal democracies. But Europe has leverage. Europeans need to use this to defend their continent with less America and resist US economic coercion and territorial threats. But they should also use it to reassert Europe’s global power, just as their old ally’s is declining.

A market of wins

“We’re gonna win so much, you may even get tired of winning. And you’ll say, ‘Please, please. It’s too much winning. We can’t take it anymore, Mr. President, it’s too much.’ And I’ll say, ‘No it isn’t. We have to keep winning. We have to win more!’” (Donald Trump, speech to supporters, 2016 campaign trail)

Winning is one of Trump’s enduring fixations. This extends to his performative proclivities in foreign policy. Indeed, the president seems uninterested in the substance of policy, as long as it serves his desire for foreign policy victories, lucrative deals and shows of strength. The people around him have seized on his priorities as they try to define his agenda according to their ideologies and interests.

My ECFR colleague Jeremy Shapiro calls this process “factionalism”. In the style of court politics, restrainers, prioritisers and primacists craft versions of wins to serve up to the president. Trump’s extractive streak also inspires the billionaires and investors in his orbit, who suggest lucrative opportunities to get his interest in, say, Greenland. The intense competition means Trump’s foreign and security policy is not a finished product of some sort of previously defined strategy, but rather a continuous process of competition between the factions and outside influences, whereby the outcome (policy) is in a permanent state of renegotiation.

Presidential priorities

To be clear, Trump has some stable views about the world and America’s place within it. These seem to come from long-held grievances about US trade deficits and security alliances, as well as his disdain for liberal democracy and affinity with illiberal strongmen. Accordingly, his administrations have started a trade war with the world in both terms. They have also consistently demanded bigger contributions from allies for American protection. And they have generally been willing to use leverage to force America’s allies into a corner on trade and security. The same cannot be said for America’s traditional rivals. China’s leader Xi Jinping and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin have seen less US leverage and more dealmaking than with previous American presidents, given Trump has unburdened himself of the normative considerations of his predecessors.

Besides these beliefs, Trump appears to have few ideological priors on matters of national security. Private anecdotes and media reports suggest he does not spend much time going into substance of foreign policy. He also, by his own admission, has a short attention span. His instincts seem to tilt towards restraint, but this is selective. As Shapiro has documented, the president seems distinctly doveish towards powers like Russia and China. Yet he has authorised military action against, for instance, Houthis in the Red Sea, Iran and Venezuela.

Ultimately, “winning” seems far more important than ideology. Throughout his second term, the president has shown a pronounced desire to score and visibly demonstrate foreign policy victories, prioritising headline impact over everything else. In some cases, these claims rest on genuine but limited achievements. Notably, US pressure and regional mediation contributed to the 2025 ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. This enabled the release of Israeli and foreign hostages held by Hamas: a concrete humanitarian outcome. But there is no sign this ceasefire will hold, nor turn into a durable peace in the Middle East.

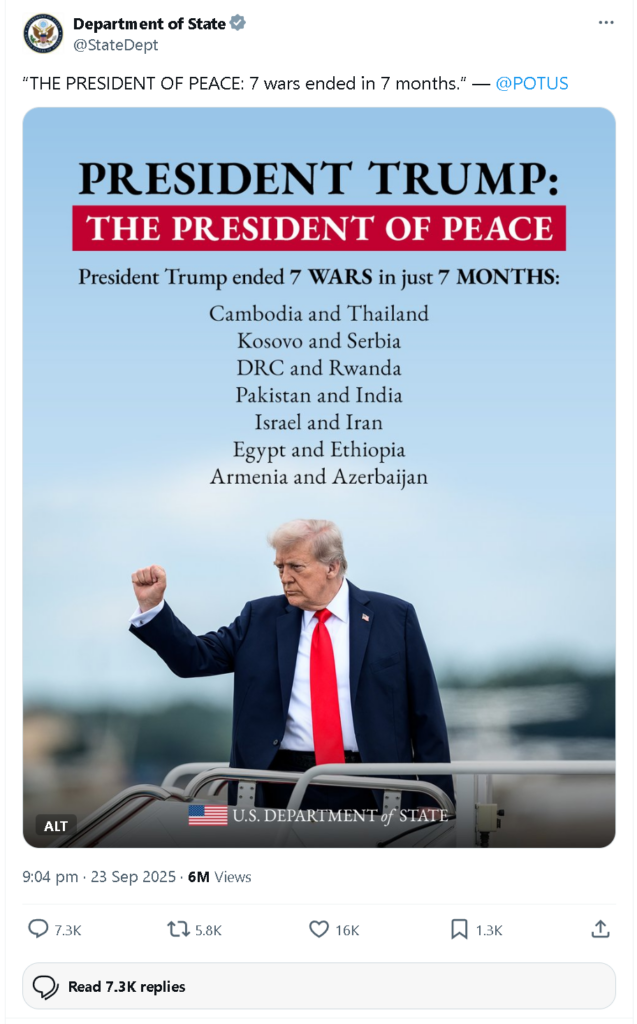

Rather, the president’s most sweeping claims often rely on exaggeration or relabelling short-term developments as historic breakthroughs. His assertions that he ended six, seven then “8 Wars PLUS” conflates fragile ceasefires, de-escalations and even non-wars into a single narrative of triumph. Overall, Trump prioritises symbolic and performative wins over strategic ones; the point is that the president can declare a victory and move on.

Of course, making lucrative deals is what “winners” do. Trump’s extractive foreign-policy approach is visible not just in the economic and trade realm, but also in security. Since returning to office, the president has repeatedly framed US engagement abroad through financial or commercial gains rather than value of alliances, shared rules and long-term stability. He expresses his goals as “getting paid”, “getting something back” or making money for the US.

Winners are also strong. The motto “Peace through strength” and repeated criticism of Joe Biden’s weakness as a cause of Russia’s aggression of Ukraine was at the centre of Trump’s 2024 campaign. Similarly, Trump’s actions and rhetoric during both terms in office show an ambition to demonstrate strength and decisiveness in foreign policy, often prioritising an immediate show of “toughness” over long-term concerns.

These three priorities combine with the factional policymaking process to create the unstable equilibrium that characterises Trump’s defence and security policy.

Factional warfare

As Shapiro describes, Trump’s first term saw the president become increasingly convinced of a “deep state” collusion to undermine his agenda. This has led him to replace the traditional “interagency” policymaking process with a factional one. In the interagency model, the National Security Council (NSC) coordinated the work of the Department of State, the Pentagon and Intelligence agencies. The agencies deliberated US foreign policy in a structured, bureaucratic manner. They vetted proposals carefully and presented the president with several policy options from which he would choose “the best” option. While competition always existed, the options and ultimately US foreign policy tended to emerge from institutional consensus.

But the second Trump administration has gutted the NSC, sharply reducing its size, influence and expertise. In May 2025 the president dismissed his national security adviser, the primacist Mike Waltz, along with a host of senior policy professionals. He has replaced them with a much smaller cadre of loyal appointees. The NSC is effectively led by secretary of state Marco Rubio (also a primacist, but a loyal one), who has also assumed the role of acting national security adviser. The NSC thus no longer functions as the centre of interagency coordination. Instead, national security decision-making has become increasingly centralised within the White House.

The president still has plenty of help choosing “the best” policy option. But under the factional model, these choices emerge from competition among Trump’s appointees to define his agenda according to their ideological outlook. The restrainers and prioritisers have mobilised around the vice-president J.D. Vance. The primacists have coalesced around Rubio. The prioritisers cluster in the Pentagon, which is led by culture warrior Pete Hegseth, so have to work through him to get to Trump.

The president states his preferences plainly and the factions respond in kind—offering arrangements that give Trump the visible victories, lucrative deals and shows of strength he craves. But the factions are also entrepreneurial, often using such wins to lure the president’s limited attention and lack of interest in details to their pet projects. Businessfolk and billionaires in Trump’s orbit have also made their foreign policy views known and are promoting their own ideas. The Greenland scheme reportedly came from billionaire Ronald Lauder back in 2018; the Gaza plan was concocted between Trump’s son in law Jared Kushner, special envoy Steve Witkoff (Trump’s friend and long-time business associate), and Ron Dermer, the closest advisor of Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu. Billionaires Miriam Adelson and Bill Ackman, Trump’s two biggest donors, have weighed in to shape policy on Israel and Iran. Witkoff and Kushner have also become highly influential on Russia and Ukraine.

Of course, the role of business interests and donors in US domestic and foreign policy is not new. Unusual here is Trump’s open and unapologetic embrace of an extractive worldview: foreign policy exists to generate deals, repayments and visible commercial wins. Conflicts are re-framed as development opportunities. Gaza is a property and infrastructure problem that should be resolved through real-estate development, rather than meticulous negotiation with due attention to historical details and politically sensitive issues. Unlike previous presidents, Trump does not mask his business logic in strategic or moral language; nor does he allow his policy to be limited by any normative or institutional constraints.

This being foreign policy, outside actors have also entered the game. They mostly align with the primacist faction in their quest to keep America engaged in their respective wars and have crafted wins of their own for the president. Israel, for example, gave Trump a show of strength via its military strikes on Iran in June 2025. European leaders carefully choreographed a NATO summit (among other things), with the alliance’s secretary-general Mark Rutte framing the pledge from European members to spend 5% of GDP on defence as Trump’s “BIG” success.

This all combines to produce consistent inconsistency in US defence and security policy across the western hemisphere, Iran and Israel, China and Taiwan, and Russia and Ukraine.

The western hemisphere: When foreign is domestic

Trump has long framed crime in US cities and drug trafficking as “liberal problems”. During his first term, the Justice Department indicted Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro on narco-terrorism and cocaine-trafficking charges. In his second term, Trump and his cabinet use a narrative connecting drug flows from Venezuela to threats to America’s national security. Further east in the hemisphere, Lauder reportedly first approached Trump with his thoughts about Greenland in 2018. Back then, Trump framed the acquisition as a purchase. But his appetites were curbed by half-functioning interagency process that has since degraded.

The state of play: The national security and defence strategies prioritise homeland security and the western hemisphere. The former heralds “a Trump corollary to the Monroe doctrine”; the latter includes five explicit references to Greenland and its importance for America’s national security. Nevertheless, the documents likely tell Europeans more about the state of the factional competition at the end of 2025 than the strategic direction of Trump’s America.

The deployment of troops to the southern border reflect longstanding restrainer demands. Much to the chagrin of these restrainers, however, on January 3rd Rubio and the primacists assisted Trump with a hat-trick of wins in Venezuela. The capture of Maduro and his wife was just the kind of impressive military operation that appeals to Trump. It was a show of strength that came with the opportunity to post about his victory on social media. And, on the surface, it appeared to come with oil deals. The success of the Venezuela operation seemingly emboldened Trump, who quickly turned his attention to Iran and Greenland.

The first year: Over 2025, the second Trump administration militarised Democrat-led cities and surged resources to the southern border, also amassing the largest US naval presence in the Caribbean since the Panama crisis in 1965. This was all part of a supposed crackdown on crime and drug cartels, with Rubio and Vance both adjusting their rhetoric to make its contradictions more digestible for the MAGA base. Trump’s longstanding interest in acquiring Greenland rumbled along in the background throughout the year, causing periodic diplomatic crises with NATO ally Denmark—for instance, in response to alleged US influence operations in the territory.

In mid-August, the US began its military build-up in the Caribbean. It began to strike what it claimed were “drug boats” in September, which by the end of December had resulted in more than 100 civilian deaths. On October 1st, the White House formally notified Congress that America was engaged in a “non-international armed conflict” against drug cartels in the Caribbean. These operations took place against a backdrop of a disproportionate naval build-up off the Venezuelan coast, which Hegseth in November rebranded “Operation Southern Spear”. They also took place in the framework of a fierce behind the scenes battle between restrainers and primacists to convince Trump of the best way forward.

Restrainers opposed military intervention in Venezuela. In their view, the US focus on the homeland and the southern border was always supposed to happen instead of, not alongside, US military adventures and commitments abroad. They also drew parallels between Venezuela and Iraq—not least the dubious intelligence around the “narco-terrorist” accusations levelled at Maduro. Restrainers thus saw the survival of the Maduro regime as a lesser evil than what they assumed would turn into a lengthy invasion. Before Trump cut off diplomatic channels in October, negotiations had reportedly resulted in an offer from Maduro to provide US companies near-exclusive access to Venezuela’s oil and minerals. Trump himself acknowledged that Maduro offered “everything” to head off escalation. An extractive win was on the table even with Maduro still in power.

But Rubio and the primacists topped this up with offers of a show of strength and a headline-grabbing victory. Part of the problem for restrainer officials was that they had undermined their own position by adopting the primacist narrative that wove the evils of the Maduro regime into the domestic “drugs and crime” story. Primacists duly weaponised this to argue that a secure southern border sometimes involves regime change. They also sold removing Maduro as a way for Venezuela’s oil sector to open up under a new government and push Russian and Chinese companies out of the country. But neither restrainers nor primacists inconvenienced the president with the practicalities of their version of the extractive deal. US oil executives have since made clear that Venezuela’s oil sector is a financial black hole, requiring massive upfront investment with little prospect of returns. No matter, the meticulously planned operation went ahead and returned no American casualties.

Trump then claimed his victory and moved on, rapidly. In an interview with the Atlantic on January 4th, the president made clear his newfound enthusiasm for interventionism may not end with Venezuela. He said America “need[s] Greenland, absolutely” because the territory is “surrounded by Russian and Chinese ships”. This snowballed into in a two-week long transatlantic crisis. It also underlined the lack of institutional constraints in the administration and the role of Trump’s business network (in this case, Lauder) in pitching ideas to the president. Lauder’s project likely appealed to Trump’s aim to assure his own historical greatness through territorial expansion. It also reflects the president’s view of sovereignty and territory as something powerful states take when they want.

Behind closed doors, people close to the administration suggest neither the primacists nor the restrainers support the acquisition of Greenland.[1] The restrainers oppose it since it would involve investment and financing that may be siphoned away from their domestic priorities, with little hope of profiting from Greenland’s energy resources any time soon. A potential conflict with an ally for territorial gain also clashes fundamentally with their desire to avoid overseas military entanglements. The primacists are loath to imperil America’s global power by damaging the NATO alliance, possibly beyond repair. Only hardline confidants like Stephen Miller, Trump’s homeland security adviser, pushed openly for military takeover of the island, claiming “nobody is going to fight the US over the future of Greenland.”

Trump’s Greenland escalations gained traction in large part because no disciplined interagency process exists to filter them out. Despite their private misgivings, restrainers and primacists in the administration did not oppose Trump’s Greenland plans. Trump prizes loyalty, after all. The factions instead fought over how to reframe and implement Trump’s ambitions. Rubio insisted America would buy Greenland, while attempting to reassure NATO and Congress with remarks that the administration planned “to eventually purchase Greenland”, as opposed to using military force. Vance recast the idea as a tactical show of leverage from the president, consistent with the territory’s importance for America’s missile defence. And just like that, Lauder’s near-decade old idea became US policy.

The next move: At January’s World Economic Forum in Davos, Trump announced he had reached the “framework of a future deal” with Rutte and stepped back from threats of tariffs and military force. This “deal” reportedly encompassed Greenland itself and NATO’s defence of the wider Arctic region. But the details remain undefined. Meanwhile in Venezuela, the Maduro regime remains largely intact and in control of the military and the government. The Trump administration does not seem to have a plan for what comes next: Trump has lost interest (for the moment) and factional wrangling continues. Also ongoing are the US navy’s operations in the Caribbean. Their focus on stopping subsidised oil flows from Venezuela to Cuba suggests the intention is to apply indirect pressure on the government in Havana, where regime change is reported to be Rubio’s longstanding goal.

Iran and Israel: When strikes are restraint

The Middle East was at the heart of the Trumpist foreign policy revolution of 2016. The restrainer movement is deeply rooted in the experience of America’s war in Iraq in 2003, which triggered a backlash in the party against the Bush-era elite. Trump ran on a combination of a restrainer and Iran-hawkish platform in 2016, promising to bring US troops home from the region and end costly “forever wars”. In 2024, he campaigned on the promise of ending the Israel’s war in Gaza, and early in his term in office reached out to Iranian leadership to broker a new nuclear deal. In June 2025, the US joined Israeli military strikes on Iran’s Fordow nuclear facility.

The state of play: After the strikes in June, the primacists and Israel seemed to have given Trump just the kind of win he needs: a show of strength that enabled him to declare victory and move on. But this soon evolved into something less settled, with restrainers claiming such one-off surgical strikes were in keeping with their vision, and primacists (and Israel) viewing Iran as unfinished business. In December 2025, a wave of anti-government protests swept Iran. Trump threatened miliary strikes in support of the protesters, seemingly emboldened by the success of the Venezuela operation. This might have finished said business for Israel and the prioritisers. But Trump backed down reportedly under pressure from Saudi Arabia and other powers in the region. At the time of writing, Trump’s rhetoric had evolved into demands for a deal and “NO NUCLEAR WEAPONS” ahead of talks scheduled for February 6th.

The first year: The restrainer versus primacist battle began at the very start of the second term. Vance and his advisers, backed up by top-tier officials in the Pentagon and the Office of National Intelligence, were eager to avoid military confrontation with Iran and pushed for a political solution to deny the country the ability to build nuclear weapons. They acknowledged that securing extended restrictions on Iranian nuclear activity would require US concessions, such as economic benefits for Iran and limited uranium enrichment consistent with civilian needs.

The primacist camp included Waltz, as well as the head of US Central Command, General Michael Kurilla and senators Tom Cotton and Lindsey Graham. They aligned with Netanyahu’s approach, which involved the full dismantling of Iran’s nuclear programme via military force. Their view was that Iran should not be allowed to enrich any uranium, and they argued for provisions like restrictions on missiles.

Many influential people around Trump aligned with the primacists in pressing for military intervention and regime change. They included representatives of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire, most notably Fox News host Mark Levin. But also billionaire contributors to Trump’s campaign, including Ackman, who made multiple explicit pro-intervention statements on X in mid-June 2025; and Adelson, whom Trump credited in his speech to the Israeli Knesset in October 2025 as having helped shape US decisions on Israel.

But Vance and the restrainers also had the support of strong MAGA voices outside the cabinet. These included congresswoman Majorie Taylor Greene, TV host Tucker Carlson, former White House advisor Steve Bannon, and executive director of American Conservative Curt Mills. All were, and remain, against US alignment with Israel. In their eyes, the underlying goal of the military operation was to sabotage diplomatic talks and pursue regime change. Vance himself worried about “mission creep” into a regime change operation and was staunchly against military action. In private conversations, restrainers claim that Kurilla, Waltz, Graham and Cotton tried to persuade Trump to redeploy the forces the US used against the Houthis in March to attack Iran. They say the primacists deliberately tried to conceal the costs of a potential military operation against Iran and were searching for any evidence that Iranians were supporting the Houthis to justify expanding the military operation.[2]

In keeping with his instincts, the president initially leaned towards the restrainer approach. In public, he maintained a credible threat of use of force to incentivise Iran to make a deal, and did not rule out US participation in Israeli-led strikes. In private, he opposed the Israeli strikes, which led him to persuade Netanyahu to delay Israel’s military initiative in April and once again in May. Witkoff did the same, and the envoy’s initial offer to Iran would have allowed it continue limited nuclear enrichment, subject to strict monitoring. Under pressure from primacists and Israel’s leadership, however, the US position on the nuclear deal hardened to no enrichment.

Indeed, between April and the end of June, Trump’s Iran policy and public discourse underwent more fundamental shifts. He moved from opposing military action, to distancing America from Israel’s strikes, to approving US participation in the Israeli bombing of Iran and claiming ownership over the operation’s reported success. Why this turn? Why did the primacist faction prevail? Waltz and his entire team were out of the picture, which arguably had something to do with their hawkish position on Iran and Russia. All indicators suggested that Trump would not intervene in Israel’s conflict with Iran.

The New York Times reports this began to shift after a phone call between Trump and Netanyahu on June 9th. In that call, Netanyahu said the strikes were going ahead, with or without the US, and that Israel already had forces on the ground. The ingenuity of Israeli planning reportedly impressed the president, who after the call told his advisers: “I think we might have to help him”. Following Israel’s precision strikes on June 13th, Trump reportedly began to change his mind about his public rhetoric and claim some credit for Israel’s success. That is, Israel’s show of strength moved him from opposing Israel’s military intervention to supporting it, or more accurately, “owning” Israel’s military accomplishments.

Ultimately, the strikes gave Trump an opportunity to show off America’s strength and counter the “Trump always chickens out” (TACO) criticism. They also helped enhance US leverage in nuclear negotiations with Iran. Israel’s leadership thus delivered a win for Trump. But Trump remains a dove militarily and, again, moves quickly on having claimed his win. This was most visible when he lashed out at Netanyahu before taking off for the NATO summit in the Hague, criticising Israel for bombing Iran after the ceasefire had been announced.

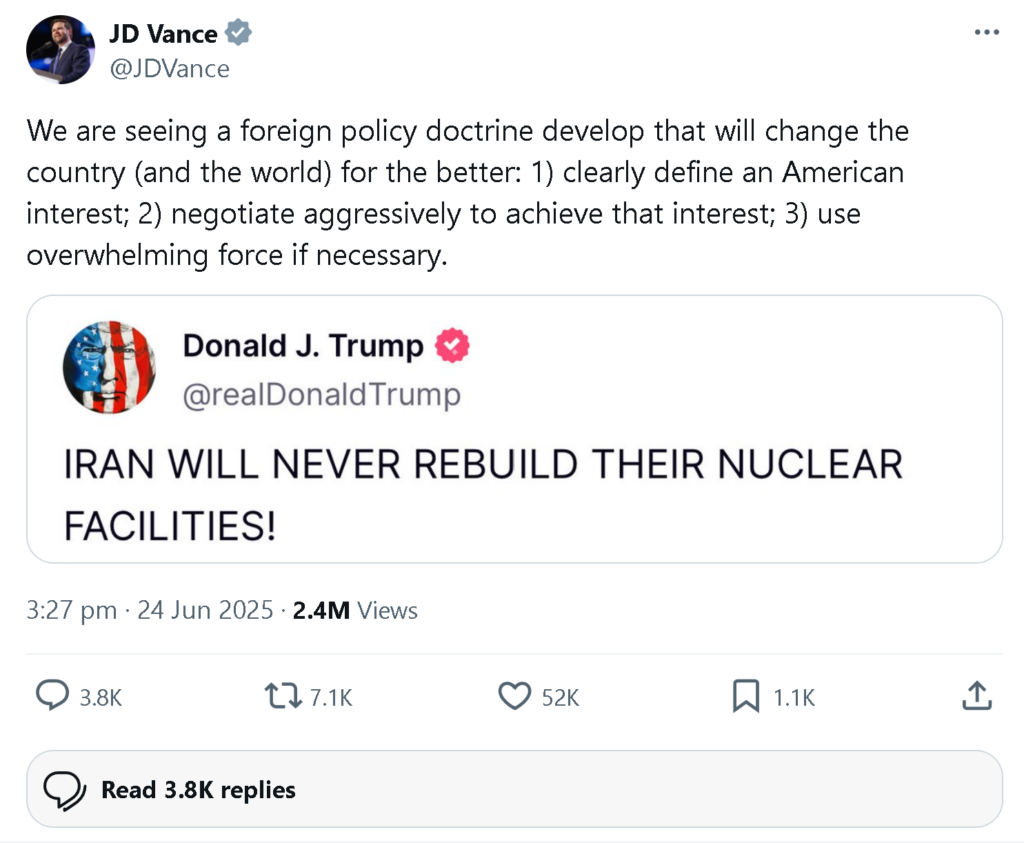

Through the strikes, the president disappointed restrainers in his cabinet. He publicly undermined Gabbard and his own intelligence agencies, claiming their assessment of Iran had not decided to build a nuclear bomb was wrong. And yet, Trump’s quick exit from the “joint military venture” allowed Vance to frame the US intervention, which was in fact a primacist project, in restrainer terms. He argued it was an example of effective surgical action essential to halt Iran’s nuclear weapons development, while managing to keep the US out of another “forever war” in Middle East. He also commended it as a tenet of Trump’s new “foreign policy doctrine”.

But the primacists continued to express concerns about the Iranian threat. They questioned whether the enriched uranium was genuinely destroyed or simply moved from the Fordow facility before the strikes. Jeniffer Griffin, FOX news chief national security correspondent, was at the forefront of this effort. Hegseth, her former colleague, contradicted her in a fiery exchange at the end of June. By November 2025, the situation in Iran was best described as a dangerous stalemate. No diplomatic talks were happening, the US had no clear idea of status of Iran’s uranium stockpile and there was no external insight into the state of Iran’s nuclear programme.

The next move: Far from aiming to finish unfinished business, Trump’s new threats seem to have emerged from a sense of invincibility after the wins of Venezuela. They are likely tactics of intimidation, based on the assumption that the Maduro operation shows Trump does not “always chicken out”. Strikes on regime targets in Iran would carry serious risks of retaliation that Trump has consistently sought to avoid. Whether primacists or restrainers get what they want will therefore depend on how costly military action would be in terms of the risk of escalation and US casualties. Back in March 2025, Trump quickly disengaged from the campaign against the Houthis once American costs became clear. This is likely a more reliable indicator of where he goes on Iran than either the June 2025 strikes or the Venezuela operation. His late January shift to nuclear dealmaking suggests that may be a fruitful route for restrainers and US allies in the region to focus the construction of their wins.

China and Taiwan: When deals are deterrence

When it comes to China, Trump’s restrainer tendencies have been on show since he first became the Republican presidential candidate in 2016. “Strategic rivalry” does not seem to feature in his vocabulary. He has refused to confirm whether he would defend Taiwan if China pursued “reunification” by military force, and has accused the former of stealing America’s advantage in semiconductor technology. Across two terms, Trump’s China policy has focused on imposing high tariffs on Chinese imports to force a better trade deal for the US.

The state of play: Trump’s China policy departs from the preferences of both the primacists and the prioritisers. Hegseth focuses more on culture wars than actual wars, which leaves Colby to deal with matters of policy. This has resulted in an uneasy hybrid: as staff in the Pentagon try to enhance America’s capacity to fight China, Trump pursues economic detente with Beijing (while Hegseth posts memes on social media). Trump’s tendencies are also a rupture from the bipartisan consensus that the deterrence of China should include strong economic security measures.

The first year: Primacists and prioritisers agree Taiwan is crucial for US national security. They also agree China is America’s greatest strategic rival. Colby and his team see Taiwan as a first line of defence against Chinese expansion to more islands in the Indo-Pacific. Their “deterrence by denial” doctrine demands a robust military buildup and burden-sharing with Indo-Pacific allies in the region to convince China’s leaders aggression on Taiwan would fail.

But Trump seems to have limited interest in confronting China. According to former administration officials, early in his second term Trump forbade any discussions of China war plans in the Pentagon; the officials claimed Trump was furious about Elon Musk’s presence in such talks. This was not because it was in breach of protocol but because the president objected to them happening at all.[3] Other media reports suggested the president tends to downplay the risks of Chinese military action against Taiwan, viewing the island primarily as a bargaining chip in the wider US-China relationship. Some commentators, including former officials, argue that Taiwan could be part of a grand bargain with China that includes trade and export concessions.

These tensions are visible in the national defence strategy. In the document, any language alluding to power projection in the Indo-Pacific nestles under a White House comfort blanket. On page three, for example, it states that Trump “seeks a stable peace, fair trade, and respectful relations with China, and he has shown that he is willing to engage President Xi Jinping directly to achieve those goals”. It adds: “We will open a wider range of military-to-military communications with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) with a focus on supporting strategic stability … deconfliction and de-escalation.” But the next paragraph pivots to deterrence. It claims that the US is “clear-eyed and realistic about the speed, scale, and quality of China’s historic military buildup” and the goal to “set the military conditions … to prevent anyone, including China, from dominating us or our allies”.

A similar disconnect exists in the administration’s economic security policy. The national security strategy emphasises US goals to counter China’s coercive economic practices, protect America’s technological advantages and secure US supply chains. But the president seems happy to deal with Beijing bilaterally. In April, Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese imports which gradually escalated to 145% in a tit-for-tat tariff war. China also slapped global export controls on rare earths. This forced the administration into retreat, with Trump granting Beijing concessions on sensitive technologies in exchange for a pause in the export controls. Later in 2025, president allowed China greater access to advanced Nvidia microchips. On chips, the factions seem to be doing what they can to nudge things in their preferred direction. The Financial Times reports that, while the Commerce Department relaxed export restrictions on the sale of Nvidia’s H200 chips to China in January 2026, the State Department is pressing for tighter controls to curb the approval of these licences.

The next move: US policy on China and Taiwan will likely remain caught between the president’s ambitions, and the administration’s stated goals and its practical constraints in implementing them. China showed it would not hesitate to impose such constraints in response to Trump’s tariff escalation, which seems to have been driven purely by tactics not strategy. The president now appears keen not to disturb his tentative ceasefire with Beijing. It therefore seems unlikely that Trump would sign off on robust US military containment of China in the Indo-Pacific, despite the factions’ common interest in deterring Beijing. And if Shapiro is right about Trump’s aversion to escalation with “strong” countries, the president will remain opposed to military planning for a Taiwan contingency. In early 2026, Trump moved the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier group from the Indo-Pacific to the Persian Gulf to threaten the less conventionally powerful Iranian regime.

Russia and Ukraine: When profit is peace

Trump appears to harbour great mistrust towards Ukraine: he has repeatedly blamed the country for his first impeachment, for his 2020 election loss and for allegedly concealing Joe Biden’s supposed corrupt activities there. Trump’s instinct to disengage from the war in Ukraine was especially evident during the 2024 election campaign. He repeatedly vowed to “end the war in 24 hours”, insisting he could press both sides into a deal. That deal has persistently failed to materialise, and Trump has threatened to walk away from the whole thing on more than one occasion.

The state of play: Witkoff and Kushner, aligned with Vance and the restrainers, are offering Trump a quick deal through territorial trade-offs and normalisation with Russia. Primacists and Europeans, aligned with Rubio, are trying to re-anchor talks around deterrence and security guarantees. In December 2025, Witkoff’s so-called 28-point plan was leaked to the media. This emphasised Ukrainian concessions on territory and sovereignty, likely with the aim of convincing Putin to let Trump have his elusive win. But the backlash from Kyiv and its allies in Europe, as well as Congress, enabled Rubio to partially reassert control by insisting on quasi-Article 5 security guarantees and bigger post-war armed forces for Ukraine. Primacists acknowledge, however, that the White House will use these changes to intensify pressure on Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, to make concessions on Donbas.

The first year: Trump quickly appointed duelling envoys, Witkoff and General Kieth Kellogg, to set the tone for the restrainer versus primacist battle on Ukraine. Witkoff was already in Trump’s good books, having brokered a short-lived ceasefire between Israel and Hamas in the weeks before the president took office, and it seems Trump viewed him as capable of pulling off a similar win in Ukraine. Kellogg’s vision was somewhat different. He argued that to end the war, the US should use its ample leverage and escalate to de-escalate. But this sat uneasily with a cabinet increasingly encouraged by Vance to focus on normalisation with Russia. By March, Kellogg had been demoted to “Ukraine envoy only” and marginalised from core negotiations. He stepped down altogether in January 2026.

A similar division between primacists and restrainers existed in the US government and Trump’s cabinet. The view of the primacists is that preventing a Russian victory is the only way to uphold American credibility and NATO cohesion, and deter future Russian aggression. Graham was initially among the staunchest primacists on Ukraine. The restrainer camp, represented at the most senior level by Vance, favours a negotiated settlement, a reduction of US assistance and the transfer of responsibility for Ukraine’s defence entirely to Europe. They see political and economic reset with Moscow is strategically necessary because a less hostile relationship between Russia and the West could reduce the former’s dependence on China. Escalation with Russia, in restrainer eyes, also locks America into an open-ended conflict with no clear advantages for the homeland.

Publicly, both camps adjusted their rhetoric over the course of the year to remain in sync with the president. But privately, they continued to push competing solutions. This clash became visible in April, around the time of the proposed US-Ukraine critical-minerals deal. Graham framed this as win for Trump by boasting that Ukraine was home to $10trn-$12trn in minerals and rare earths. He sweetened it by claiming America should secure these resources before Russia or China did. But Vance helped derail the deal through the infamous Oval Office confrontation with Zelensky. Former officials say that, shortly after the incident, restrainers around Vance tried to get the president to suspend intelligence sharing and weapons deliveries to Ukraine.[4] In the Pentagon, meanwhile, a group of prioritisers with China on their minds paused certain ammunition shipments to Ukraine. Trump quickly reversed this amid complaints the state department and White House had not been fully briefed.

These events stirred European leaders to enter the game as a de facto extension of the primacist camp. Seeking to shape Trump’s thinking on Ukraine was Rutte, as well as the German chancellor Friedrich Merz, Finnish president Alexander Stubb and British prime minister Keir Starmer. Through persuasion and flattery, they worked to repair relations between Trump and Zelensky and discourage an at-any-cost deal with Russia. They pressed for clear red lines before any Trump-Putin summit and urged additional sanctions on Moscow should the Russian president fail to agree to a deal. Through charm diplomacy and carefully staged symbolic gestures, they served up “wins” for Trump—from royal receptions to defence-spending commitments from NATO allies.

As one senior European official put it, their goal was to move Trump from a quick deal to a position of “benign neutrality” on Ukraine, while keeping America invested, politically and militarily, in European security.[5] Their efforts succeeded in buying time. Trump appeared to abandon his initial inclination to force Kyiv into accepting unfavourable terms. He also authorised weapons sales through NATO’s Prioritised Ukraine Requirements List (PURL). Indeed, he even approved US intelligence assistance for Ukrainian strikes on Russian energy infrastructure, in moves restrainers would have deemed escalatory.

Yet just as primacists seemed to be gaining the upper hand, a business-oriented camp was cooking up a win for Trump that appealed to his taste for lucrative deals. This group included Witkoff, Kushner and other businessmen close to Trump, and had full support of the restrainers. Their idea was to frame the war less as a military struggle and more as a frozen economic opportunity, and their vision of peace revolved around commercial reintegration with Russia. As the Wall Street Journal reported in November, Witkoff, Kushner and Russian sovereign wealth fund chief Kirill Dmitriev explored an array of ideas to bring Russia’s two-trillion dollar economy “in from the cold”.

This business-driven logic found its way into the national security strategy, which emphasises economic strength, transactional diplomacy and flexibility over ideological or military confrontation with Russia. This is quite a departure from both the restrainers’ and the primacists’ traditional ideological lines. Trump’s first year back in office thus ended in a fragile equilibrium, almost a compromise, between the factions. Restrainers still dominated Trump’s instinct to end to the war quickly by using leverage over Kyiv to give up territories, and a reset with Russia became the administration’s formal objective according to the national security strategy. But the primacists have slowed (though not reversed) the push for territorial compromise by re-inserting security guarantees and allied buy-in.

The next move: Of course, Putin is very likely to keep refusing the deal. This could force Trump back towards the Vance line rather than pursuing the more complicated, costly package which involves a serious commitment of US resources and European-backed security guarantees.

Everyone’s a loser, baby

“Europeans can order Patriots, but they’ll receive them in 2035. We are no longer the arsenal of democracy. That is a real constraint.” (Author’s conversation with former Pentagon official, Brussels, June 2025)

No faction has managed to assert stable influence on Trump’s foreign policy. Greenland is the president’s “thing” and an irritant for primacists and restrainers alike. Rubio served up wins for Trump in Venezuela, but the administration has no visible strategy for what comes next. The US crackdown on shadow fleet vessels sending Venezuelan oil to Cuba suggests the secretary of state may have his eye on regime change there. But restrainer backlash may (or may not) leave him disappointed, as might Trump’s focus on Greenland.

On Iran, Trump alienated the restrainers by breaking his promise to avoid new wars in the Middle East. He disappointed the prioritisers too, since the president’s backing for Israel’s war involved US forces and missile-defence systems prioritisers want for the Indo-Pacific. Like in the western hemisphere, primacists temporarily gained the upper hand on Iran. Yet this seems to have been more a coincidental alignment between Israel’s show of strength and primacist objectives than a durable strategic shift. Trump’s January 2026 climbdown from his bellicose rhetoric likely reflected Gulf state lobbying, as well as Trump’s pattern of taking things to the brink then pulling back. But that may not last.

On the Indo-Pacific, latent prioritiser dominance in the Pentagon seeped somewhat into the national defence strategy. But Trump’s emphasis on dealmaking with Beijing sits uneasily with Pentagon advisers’ goal of sustaining credible deterrence, and US policy on China and Taiwan remains just as unstable as it is elsewhere. Its defining characteristic seems to be the tension between the president’s instincts and the bipartisan consensus that China is America’s biggest rival and poses the gravest threat to US interests.

On Russia and Ukraine, primacists have not enjoyed the same luck as they have elsewhere. Trump has been true to form in refusing a to take a tougher approach to Russia. But restrainers are not in control either, despite their alignment with the president’s instincts and the preferences of the business interests around him. This is arguably because of Putin’s steadfast refusal to let Trump have his deal. It also reflects primacist and European efforts to reframe the terms of negotiation whenever Vance and friends seem to be crossing the line. At the time of writing, this dynamic shows little sign of changing—despite a series of direct talks taking place between America, Russia and Ukraine.

All the factions have thus lost one way or another. Lest they appear disloyal, however, all of them adapt their rhetoric to appear in sync with the president (and their base). Rubio reframes Trump’s territorial claims on Greenland in reference to America’s security interests, while leaning on prioritiser arguments to disguise his beliefs about American retrenchment in Europe. Vance, having lost out to the primacists on Iran and Venezuela, makes it all about homeland security and quick, surgical strikes—a far cry from the forever wars of the past. The factions unite in their praise for Trump as a strong leader and their disgust with European “weakness”. The national defence and security strategies reflect this private bargaining and public loyalty: the documents reconcile cross-factional compromise via ambiguity and transactionalism, offering post hoc justifications for the president’s impulses. They may, in turn, end up telling us more about the first year of Trump’s presidency than they do the next three.

Even America

This has significant implications for America’s global power. Before Trump took office, prioritisers argued the main trade-offs involved in the pivot to the Indo-Pacific would be between US presence in Europe and in the Middle East. Sure enough, the first year of Trump’s second term saw US military resources shift from one theatre to another. But it was from the Indo-Pacific and Europe towards Trump’s performative adventures in the Middle East and the western hemisphere.

Some of that reallocation fulfils the longstanding restrainer demands to surge troops to the border with Mexico. In the first two months of 2025 alone, the administration reportedly spent $328m on Trump’s border deployments. This would amount to a cumulative annual cost of $2bn if it continued at the same rate. But the Pentagon’s requested budget for 2026 reportedly earmarks $5bn more for the southern border in 2026. (For context, America’s annual military aid to Israel was roughly $3.8bn in the pre-October 2023 era.) Trump has also turned his show of strength on Democrat-led cities. This militarisation is transforming one of the world’s most durable republics from within, at a cost of almost $500m to the taxpayer over 2025.

All this has happened without the concurrent overseas retrenchment restrainers argue is necessary. The president’s Caribbean operations are costing the administration around $31m a day. One report suggested a cumulative total of $700m by January 8th, rising by $9m a day. The administration spent over $1bn in its two-month naval and air campaign against the Houthis yet failed to eliminate the threat. The non-partisanTaxpayers for Common Senseestimates the Iran strikes cost between $100m and $132m in a single night. But underwriting Israel’s defence during the 12-day war was a much greater drain: in 2025, America spent roughly as much defending Israel as it provided in direct annual aid, once missile interceptors fired during the Iran conflict are counted. As the Wall Street Journal reported in July, the US deployed two of its seven most advanced missile defence systems to Israel and fired more than 150 interceptors in under two weeks. This was nearly a quarter of such missiles ever purchased by the Pentagon; it will likely take until summer 2026 to replenish them and cost $2bn.

These may seem like trivial amounts for a country whose military spending has long dwarfed that of the rest of the world. But the administration’s burst of military activity in 2025 and early 2026 left the Pentagon scrambling to shuttle aircraft carriers between theatres and reassign weapons systems. Restrainers have long complained that Ukraine burned through high-end munitions at a pace that outstripped production. The administration has now repeated that trick in the Middle East. Assets the US might need to deter China are spread thinly, seemingly without consideration of what that means for America’s place in the world. The retrenchment from Europe, if it happens, itself undermines America’s ability to project its power elsewhere.

But most of all, Europe

The implications for Europe are clear. For decades, Trump has said he thinks allies are ripping America off in security alliances. He pushed for bigger contributions from European NATO members throughout his first term. In 2025, the administration again spelled out the burden-shifting imperative in the national security strategy: the US expects Europe to assume primary responsibility for its own security, while offering continued access to US markets, technology, and defence cooperation as inducements rather than guarantees. The national defence strategy repeats it once again in a “line of effort” all of its own.

It is now an accepted fact that Europeans need to assume financial responsibility for Ukraine. The leaders of European NATO members have committed to 5% military spending targets (except Spain). They have also earmarked over $4bn in PURL purchases for Ukraine. Less obvious is whether America can fulfil these purchases, given the strain on its attention and resources. Trump also took things a step further with his claims on Greenland’s territory. This involved threatening Denmark, one of America’s most loyal European NATO allies. As my ECFR colleagues argued in January, Europeans must now work out not only how to defend their continent with less America, but also against America. The “framework for a future deal” announced in Davos should come as no reassurance, given Trump’s long history of welching and using such agreements as leverage.

Part of Europe’s defence will have to be against Trumpists’ culture war. Both Trump administrations have shown remarkable consistency in their support for far-right populists in Europe. The second administration laid bare its affinity with these “civilisational allies” yet again in the national security strategy. Part of this seems to stem from Trumpists’ business agenda: by empowering Eurosceptics, Trumpists’ likely aim to weaken the bloc’s capacity to regulate US tech companies, maintain unity in trade negotiations and potentially resist US pressure to lift sanctions on Russia.

But there is also a strong ideological component. My colleague Celia Belin has shown how Trumpists’ views of Europe are an extension of their domestic culture war against “liberal leftists”. In this respect, conservative, Christian strongmen (Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orban, his Slovakian counterpart Robert Fico, or even Putin himself) find themselves on the right side of the divide. Translated into foreign policy, this ideological aspect conflates with the restrainer desire for a reset with Russia, meaning that direction may become consistent also on Ukraine. In short, there is no “Western response” to Russian aggression, because there is no “West”, as Europeans have understood it in the post-second world war era.

What to do when the West goes west

“My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.” (Donald Trump, interview with the New York Times, January 2026)

The coming years look daunting for Europe’s leaders. Their once great ally has no grand strategy or coherent ideological direction to, for better or worse, at least make their lives more predictable. Trump himself seems to be driven by short-term fixations and long-term grudges, which have little to do with America’s place in the world now or after he has gone. He lends his ear to a few aids in the Oval Office and a handful of billionaires and strongmen outside it. He has gutted the federal government, slashing the agencies that in previous administrations vetted and filtered the policy options that reached the president. If they can get his attention, the factions compete to serve him up quick wins; if something is his idea, the absence of the interagency process means there’s little they can do to stop him.

One constant in all this is the president’s desire to win, whether this is through foreign policy victories, extractive deals and shows of strength. The details are irrelevant. Another is the convergence of the factions on the question of “Europe”. Regardless of which faction temporarily satisfies Trump, everyone agrees US attention should shift away from European security. Washington increasingly treats Europeans less as allies and more as prey. And, whatever pledges Rubio and the primacist whisperers get to, say, keep US troops in Europe, the reality is that these troops belong to a changed America, one whose leadership does not define US interests and priorities in the same way as most European countries. Trump’s apparent determination to acquire Greenland and threats against Denmark are the most glaring example of this divergence. His militarisation of the homeland is another.

In 2025 Europeans mainly tiptoed around this new reality, out of necessity as much as naivety. Rutte, Stubb, Merz and others mixed flattery and persuasion with purchases of US weapons and liquefied natural gas. They proposed edits to US positions and plans. Crucially, they also ducked public confrontation with Trump and dodged overt alignment with Democrats. This achieved small temporary reversals of the administration’s more alarming propositions. But it also created a cycle in which Trump returns quickly with new, more extreme proposals: territorial grabs in the Arctic, more tariffs, more insults. Each escalation feels more shocking than the last. Yet Europeans remain locked in reactive mode because their structural relationship with America has not changed. Europe remains dependent on America for security, while Russia wages a full-blown war next door. Trumpists thus always have the upper hand.

Even in the aftermath of the Greenland crisis, European officials and diplomats are still grappling with the question of who to listen to when it comes to the Trump administration. In Davos, the Secretary of Treasury Scott Bessent warned against over-reacting to Trump’s territorial claims and escalating the situation. The Democratic governor of California Gavin Newsom told Europeans to start showing Trump the strength he respects and hit back. But Europe’s choices in dealing with the Trump administration and its implications for the world do not have to be either or. They can and should be both at once.

Three steps in the right direction

Newsom is right: Trump only respects strength. But Europe’s security dependence on the US means the former does not have the luxury of an open rupture. Europeans will have to keep using flattery to buy time to address the structural imbalance. Yet Trumpists would not be attacking Europe so brutally if the continent did not have some things one or another of the factions wants. To introduce “more Newsom” to the relationship, Europeans need to identify what these things are and learn to use them. They should also use their leverage to defend themselves against Trumpist assaults in the security, economic and cultural realms. What Europeans should not do is hope the US will revert to its old responsibilities in the global order. They should instead have the confidence to take advantage of America’s diminishing global power to reassert some of their own. Realism is essential. But China is not the only power capable of filling the holes left by the US.

The following three steps would be a good place for Europeans to start.

Rewrite the rules

As I argued in Foreign Policy in December, the EU and European countries need to set clear expectations for America. “Red lines” tend to fade in sunlight, but Europeans should restate them nonetheless on Greenland and Ukraine and then stick to them. They should also ensure the administration knows US interference in European domestic politics is one such line.

European leaders must not allow themselves to be manipulated into bilateral negotiations with America. The European Commission holds full competence on digital policy and should be forceful with that authority, for instance, by using (if necessary) its anti-coercion instrument. This would allow the EU to implement various forms of economic retaliation, including tariffs, export controls and procurement restrictions. But coordination through formal EU structures is a fantasy on such issues as Ukraine, Russia sanctions and even Greenland. This is because the unanimity requirement allows individual member states to act as spoilers.

Instead, Europeans should work through an informal coalition of member states and like-minded partners. Members of this coalition should share a common agenda and have assets that can become leverage. The group is already taking shape: the leaders of Germany, Finland, France, and the UK have long coordinated their Trump diplomacy. They should now welcome Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway (and Canada) to the fold. These countries have already come together in support of Denmark on Greenland. But they need to go beyond symbolic troop deployments. Now they need to arm themselves with a much stronger combination of assets and capabilities, and be ready to use them.

Audit Europe’s assets

I also argued in December that Europeans need a comprehensive checklist of assets Trump’s America values and does not want to lose. Member states and other coalition members should conduct their own audits. But this should extend into the EU single market, which is one of the world’s largest for US tech firms, agribusiness, services and digital platforms. Washington depends on Europe in many other areas, including some European companies’ role in advanced manufacturing (for instance of microchips) and critical technology supply chains. In early 2025, my ECFR colleague Tobias Gehrke published a breakdown of the EU’s economic “cards” across trade, technology, infrastructure, finance and people-to-people relations.

The coalition should aim to build on this and extend it to other areas where Europeans hold specific assets that can be turned into leverage. For instance, European investors jointly hold approximately $3.6trn in US treasuries. At the end of January, Denmark’s Pensions Fund announced it was selling its $100m holding of US government bonds. This alone was likely not decisive in triggering Trump’s “framework of a future deal” for Greenland. But it demonstrated how Trump’s volatile behaviour can affect the value of US bonds, and investors’ decisions along with them. Moreover, taxing and regulatory power over US services is a source of European leverage. This is because balance in US-EU trade in services tilted decisively in America’s favour last year, with the EU buying roughly $300bn from the US while selling back only about $200bn. Finally, the EU controls most frozen Russian sovereign assets and the legal mechanisms needed to use their windfall profits. The US therefore cannot “bring Russia in from the cold” without favourable European legal decisions and financial resources.

Prove strength exists in pluralism

As “the father of realism” Hans Morgenthau explained all those years ago, political power is above all a psychological relation. For Europeans to effectively exercise political power, they need to get better at playing the psychological game. This means adding threats to their repertoire of flattery and persuasion. And if one good thing comes from the cacophony of actors, leaders, institutions and languages in the EU, member states and their allies, it is that enough of them exist to divide up the tasks that lie ahead.

Rutte, Stubb, Starmer and other “friends” of Trump should continue their personal diplomacy with the president. But Trump needs to believe his friends in Europe are holding back a more punitive response. This means some coalition members should become “frenemies”, ready to threaten the US and play their cards without hesitation if lines are crossed. Friends should do the ego work. Frenemies should make credible threats. Who takes on which role should sometimes surprise the administration. This is the only way Europeans can escape the cycle of flattery and reactivity to America’s strategy of non-strategy.

Threats should imply real costs for the US. But they should also include clear ways for the administration to fold. The cooling of Trump’s rhetoric on Greenland is a good example. The volatile reaction of the bond markets was likely more decisive that anything Rutte put on the table. The secretary-general certainly did not offer Trump anything Europeans had not offered before. Rutte rather gave Trump a “deal” to use as a face-saving measure as he calmed the markets.

Europeans should also appeal to the different factions and generate incentives for each of them to take Europe seriously as a power and as a partner for their pet projects. European diplomats in Washington need to get better at connecting with the different factions in the executive branch. So far they have focused on primacists: by working exclusively with team Rubio on Ukraine, they have mostly tried to circumvent the restrainers and the prioritisers. But Europeans need to recognise they have allies in the restrainer camp when it comes to curbing Trump’s territorial appetites on Greenland and preventing potentially escalatory military adventures in Middle East.

On Greenland specifically, Europeans should plug into the US domestic debate. My ECFR colleagues have explained how Europeans should raise the domestic political costs of Greenland acquisition. Their advice includes:

- Engaging with Congress to provoke discussions about the limits of blunt assertions of power. Denmark has done this well already and should be joined consistently by other traditional American partners and allies.

- Involving themselves in the US media and think-tank debate about Greenland, including spreading knowledge about actual Greenlandic public opinion, to expose the administration’s misrepresentations.

In following this advice, Europeans should aim to validate the core domestic arguments of both restrainersand primacists. They should focus on the expense (restrainers), the damage to the alliance (primacists), and limited immediate payoff (long-term wins do not interest Trump). In so doing, Europeans could help steer the outcome towards cooperation and away from continued US insistence on a land grab. Europeans should also use this technique to influence the factions when it comes to the Middle East, where domestic costs may be just as high due to the great symbolism of Iraq for the MAGA base.

Europeans should also deploy their diversity to introduce more strategic confusion and plausible deniability into their relationship with America. They should use all the languages, literal and metaphorical, they have available to them to talk to one other and issue public statements. This would enable them to use linguistic dominance over the US to reframe and reinterpret their positions when needed. For instance, Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni used her native language to talk to Italian journalists during a meeting with US President Trump in the Oval Office, introducing a degree of ambiguity in the conversation which allowed her to say one thing to the domestic audience and then slightly reinterpret it when Trump asked for translation. In short, Europeans and their allies should aim to show America more of their strength but less of their working.

Finally, “Europe” needs a coherent public narrative to counter US political interference conducted through support for far-right parties. The Trump administration often frames its attacks on the EU in the language of civilisational threat and culture wars. But the reality is that commercial interests play a big role in driving the administrations’ anti-EU agenda. Silicon Valley tech giants see Brussels as a major threat to their business models. At a time when the Trump administration is pushing to fully deregulate AI companies in the US, the EU and its member states retain the commitment and capacity to regulate big tech. Europe’s leaders should therefore talk to European people. Instead of waging a culture war with Washington or with the far right, European leaders must highlight the commercial motivations underpinning the Trump administration’s attacks on Europe.

A world not long for this world

So far, Europeans have coped with Trump and his administration as well as they could. But Trump seems much more responsive to the strategies of countries like China that immediately impose costs on the US in response to his disruptive policies. Europeans must now combine their tactics for “keeping America in” with a strategy to defend themselves against the US, using their leverage to stand up to Trump and his administration when they threaten European interests or indeed European territory.

But they should also keep an eye on the longer term. Trump’s America is showing the world that it is policy, not only cash, that defines capabilities. This applies to European power, too. If “Europe” does not know what it wants to do without America, no amount of military spending will turn it into an equal partner. European objectives can remain derivative of American policy only in a world where these two converge. And that world seems not long for this world.

About the author

Dr Majda Ruge is a senior policy fellow with the US programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations, based in Berlin. Her areas of focus include US foreign policy and transatlantic relations, as well as the Western Balkans. Most recently, she has written and published on the foreign policy debates in the Republican party and the impact of domestic polarisation on the US foreign policy and the transatlantic alliance.

Before joining ECFR, Ruge spent three years at the Foreign Policy Institute/SAIS at the Johns Hopkins University. She has twice testified as an expert witness at hearings of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the Western Balkans. From 2014 to 2016, she lived in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where she was associated with the Gulf Research Center. Between 2012 and 2014, she was a post-doctoral fellow and lecturer at the Otto-Suhr-Institute of the Free University of Berlin, where she taught courses on international relations and nationalism.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Kim Butson, the editor every policy fellow dreams of. She vastly improved this brief and grasped every argument and nuance so thoroughly that working with her felt like co-authoring. I am equally indebted to Jeremy Shapiro for the inspiration he has provided over the past years for my work on US foreign policy, including for this policy brief through his writing on factionalism. I am also grateful to Mikhael Komin and Joanna Hosa, whose paper on Russia in the Arctic inspired the “market of wins” terminology, and Nastassia Zenovich, for her work on the profiles in this paper. Finally, my sincere thanks to the many contacts and friends in Washington from across the foreign policy tribes for helping me understand the contours of Republican debates over the past four years. None of these individuals bear any responsibility whatsoever for any errors.

[1] Author’s conversation with former Pentagon official, January 2026.

[2] Author’s conversations with restrainers and former administration officials, Brussels, June 2025.

[3] Author’s interview with former administration officials, May and June 2025.

[4] Author’s conversations with former administration officials, June 2025.

[5] Author’s interview with senior European official, Berlin, September 2025.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.