Libya’s migrant-smuggling highway: Lessons for Europe

How the lessons of Libya can help European policymakers respond to the wider migration crisis.

The refugee crisis has not abated with the coming of winter and October alone saw the arrival in Europe of as many people as in the whole of 2014. Europe is struggling to find a viable strategy to cope with unprecedented numbers, proposing a mix between policies that worked with lower numbers (such as agreements with African countries for swift repatriations of illegal migrants) and policies that respond to domestic public opinions ever more concerned about the “invasion” of hundreds of thousands of foreigners from Islamic countries.

Ultimately, this has led on the one hand to reacting through “home and justice” policies on the enforcement of borders or on detention and identification centres and the other hand on negotiations with third countries based purely on migration – this is the case both for the deal recently struck with Turkey and of the Europe-Africa summit in Valletta to be held on Wednesday and Thursday (11 and 12 November 2015).

You can download the full PDF here

But both approaches are unlikely to be effective if separated from a wider foreign policy approach. Policies that aim to “keep migrants out” by erecting fences, are usually just a boon for people smugglers, transforming (but not eliminating) flows and increasing the rate of illegal migration. Agreements with third countries on repatriations (also called “re-admissions”) are the other side of the coin and will be one of the centrepieces of the EU Council to be held at the end of the Valletta Summit on Thursday.

Re-admission agreements, with the right guarantees on human rights, can be part of a wider, alternative approach that aims to manage the probably long-term phenomenon of massive migrations to Europe. But Europe needs a bigger toolkit that includes a number of instruments of foreign policy: conflict resolution; policies that tackle the economics of smuggling, including a direct engagement with local authorities where central governments are no more effective; law enforcement against people smugglers; the creation of alternative legal channels for migrations as a development strategy.

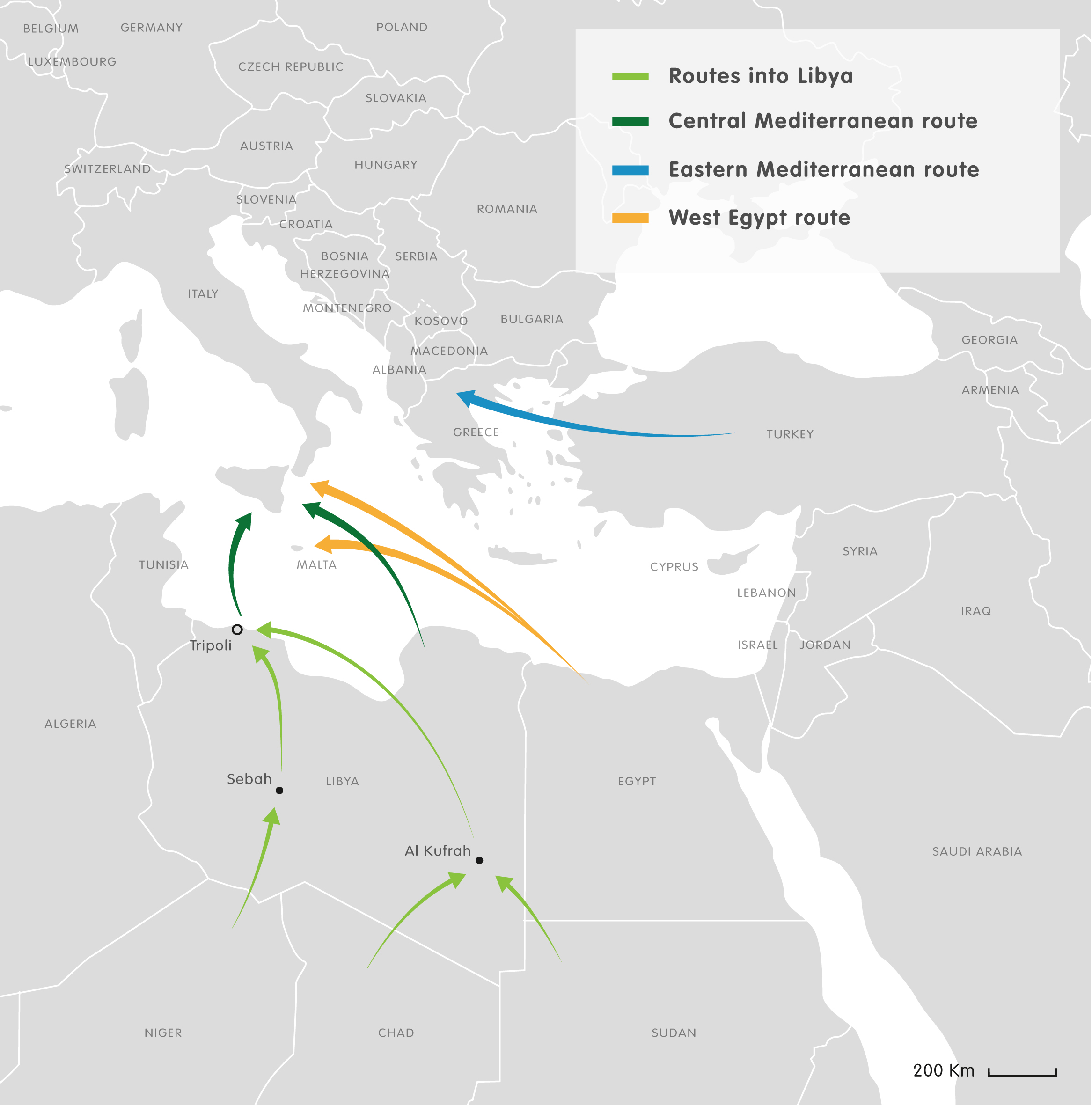

Libya, as the oldest and now second largest country of transit for migrations to Europe, is a good case study for this approach. ECFR publishes today a policy-memo on “Migration through Libya: Beyond the crisis”. The paper draws some lessons learned from the Libyan case and then makes some recommendation for European policy in Libya as well as for the reform of the overall EU policy on migrations based on the Libya case study.

There are three main lessons learned from the way migrations have developed in Libya in the past decade. First, while Libya had been a gateway for people smuggling to Europe for a long time, the massive flow of Syrian refugees was a game-changer. The relatively wealthy Syrians made Libyan smugglers rich. Early in 2015, Syrians chose to use a different route – through Turkey – and yet flows from Libya have remained almost at the same level as in 2014: the money made on them by Libyan people smugglers has been “reinvested” to bring through more sub-Saharan African migrants. In a way, Syrian refugees have helped build a “smuggling highway” that is now being used by migrants from other countries.

Second, we tend to focus on “pull factors” of migrations, i.e. the policies that we implement here in Europe which encourage migrants to come here. The paper demonstrates how EU search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean, which were considered in this category, did not result in higher number of migrants but rather in lower number of deaths in the Central Mediterranean route.

Ultimately, Libya demonstrates that “push factors” are as important: generalised violence, the collapse of countries in Africa that were once a destination rather than a point of transit, the targeting of migrants by Islamic State (IS), the violations of human rights in detention centres in Libya. These elements all played a role along with the main “push factor”: the existence in Libya of a thriving smuggling sector that supplies transit to Europe in response to an ever-growing demand.

Third, a mere securitisation of migration through fences and push-backs will not stop the flow of people. People smuggling in Libya has actually thrived owing to the restrictive immigration laws in Europe and particularly in Italy. The result of these policies is just to have more illegal, rather than legal, migrants who are unidentified (with all the security consequences this implies) and enjoy no rights whatsoever.

The Valletta Summit and the EU Council on migration this week will probably confirm and consolidate current European policies, but these will only be partially effective if they neglect the lessons learned from Libya. For instance, policies based on accepting refugees while pushing back economic migrants, without offering them any legal ways to move to Europe, will only encourage them to both disguise themselves as refugees or to move underground. The paper also warns against an emphasis on creating “hotspots” if these become, as has become visible already in Sicily, mere “push-back centres”.

The paper makes several recommendations. On European policy about migrations in Libya, the paper suggests the following:

- Work with Libyans on a different economic model for border communities. This implies legalising the trade of legal goods subsidised by the Libyan state such as petrol to separate it from the smuggling of people, drugs and weapons

- Engage with local communities and local authorities as well as with existing state institutions such as ministries or police services, based in Tripoli

- Increase monitoring and international presence to guarantee human rightsfor migrants and refugeesin detention centres and generally in Libya

- Engage in intensive mediation to support Tebu-Tuareg de-escalation. The EU should get directly involved in peace-making between these two communities by offering monitoring and mediation. Their fighting is part of a mutually reinforcing cycle with people smuggling in southern Libya.

- Build a more comprehensive law enforcement strategy to be conducted in the south of Libya in cooperation with local authorities

- Support Libyan national dialogue, but implement the above options even in the absence of an agreement.This is all the more important as tackling the smuggling economy would impact on current drivers of violence. Many of the “hubs” in the map above are also frontlines of the ongoing fighting

Based on the analysis of what happened in Libya, the paper makes also some wider recommendations for EU policy about migrations.

- Work on creating legal channels to Europe. In order to save lives and deprive smugglers of clients, the EU should assess the impact of an enhanced resettlement mechanism along with humanitarian visas. This is not to suggest completely open borders but some selective openings.

- Reception centres and hotspots: think again. These could actually become “pushback” centres as Médecins Sans Frontières has reported on the Sicilian hotspots. Even graver concerns arise when thinking of hotspots in countries with a consistent record of human right violations, and in the case of Libya, a record of violating migrants’ rights in particular.

- Re-admission agreements – handle with caution. In the absence of legal avenues of migration, an emphasis on readmissions creates human rights concerns and it could potentially backfire, creating perverse incentives for third countries to keep the number of attempted migrations high so that there is always a rationale for payments from Europe.

- Challenge regional allies. It is no secret that several Western allies in the wider Middle East and North Africa region play a role in escalating conflicts or blocking peace processes and this ultimately feeds the flows of refugees to Europe. Should we revise the assumption that it’s worth turning a blind eye in the name of strong trade and investments with these countries?

Finally, on a more general level, a typical response to the current crisis is to find extra funds for development aid. This is one of the expected accomplishments of the Valletta summit which is due to approve a Trust Fund for countries of origin of migrants. But this is peanuts if compared to remittances from migrants who actually enter Europe. Europe should make good on its promise to reduce commissions by money transfer companies on remittances by migrants. From all EU member states, these amount to €30 billion per year. This is the most massive development aid that Europe can deploy.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.