Calling Paris and Washington: Three areas for G7-G20 collaboration in 2026

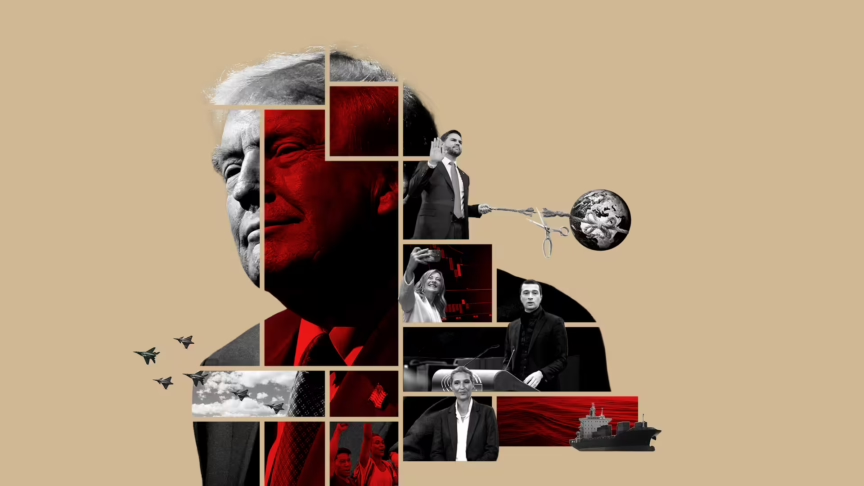

France’s G7 presidency coincides with an American-led G20. Paris will not find it easy to collaborate with the Trump administration, but it can still find meaningful areas for G7-G20 cooperation

French policymakers will have a busy 2026 year presiding over the G7. As the United States takes over the G20 presidency from South Africa, French officials are scratching their heads to figure out how they can collaborate with President Donald Trump in a bid to build bridges between the two major international forums.

Considering Trump’s regular rebukes of G7 allies and America’s rather exotic list of G20 priorities (deregulation, fossil fuels and AI), collaboration between Paris and Washington is unlikely to be smooth sailing. Yet not all hope is lost: France and the US could well find common ground in three areas.

1. The fight against global economic imbalances

France has made an unusually bold bet for its G7 presidency: trying to rally its partners around the goal of (at least) building a common diagnosis about global economic imbalances and (ideally) creating joint tools to tackle them. In plain English, this means responding to China’s growing global domination for the manufacturing of many consumer goods.

The good news is that Paris’s ambition may capture Washington’s attention. The Trump administration has long urged allies—from Europe to Japan and Australia—to adopt policies designed to nudge Beijing towards a more consumption-driven economy. Furthermore, tackling global imbalances fits neatly with the US priority of fostering economic security and de-risking—that is to say, reducing reliance on China for the supply of critical goods.

However, the practical path towards greater Franco-American collaboration on reducing global imbalances looks bumpy. First, a potential US-China trade deal—say, lower US tariffs on imports from China in exchange for Chinese purchases of American soybeans and aircraft—would see France’s G7 priority to tackle global imbalances quickly unravel. Second, France’s push to tackle global imbalances could hit a structural roadblock in the US: any meaningful attempt to fix such imbalances would require the latter to cut down on domestic consumption or investment to shrink the US trade deficit. That is not a project that any American president—let alone Donald Trump—is likely to embrace any time soon.

To keep the US on board with their G7 plans, French policymakers could take inspiration from the Think7 (the official G7 engagement group for think-tanks) and narrow their sights on two priority sectors for US economic security endeavours.

The first is legacy semiconductors, where China already controls one-third of global supply and is fast adding additional production capacity. Potential G7 proposals meant to signal government demand for G7-made chips could catch US attention. The second is pharmaceuticals; Chinese firms control roughly half of the global supply for some priority staples like antibiotic precursors. Potential French pitches to map critical chokepoints for pharmaceutical supply chains would likely interest the US. As a bonus, such proposals could also pave the way for greater collaboration with G20 members, such as India.

2. Development aid

The second potential area of collaboration between the French G7 presidency and the US G20 presidency is development aid. On paper, such an idea may sound counterintuitive: Washington has made it clear that helping developing economies is not on its radar (see: US decisions to slash USAID budgets). Yet the latest US National Security Strategy paints a more nuanced picture. In the document, Washington reckons that Western economies have no coherent plan to deploy their vast aid budgets in the many developing economies where China is making fast advances. Such a diagnosis opens a narrow avenue for France to get the US on board for a potential G7 push on development aid.

To explore this path, French policymakers could make a blunt offer to their G7 partners: establish a financial mechanism to counterbalance Chinese investment in regions where Beijing’s footprint is expanding fast, such as Africa, South-East Asia and Latin America. To get the Americans onboard, the French pitch should focus on priority sectors for American firms, including 5G infrastructure, AI and semiconductors. The pitch could also focus on repurposing existing tools (like export credit guarantees or development lending), rather than unlocking new financial resources.

USAID may be on life support, but the White House wants to keep some priority regions out of China’s orbit. In these times of global geoeconomic competition, framing development aid as an asset stands a better chance of getting a hearing in Washington than traditional appeals to solidarity.

3. Access to critical raw minerals

Access to critical minerals is a third area for G7-G20 cooperation. Despite the high interest for this topic in all G7 capitals, however, France’s challenge is that the US approach to sourcing critical minerals is not precisely collaborative. Instead, it favours exclusive deals for American firms, for the sole use of US-based supply chains.

Recent US trade agreements with Cambodia and Thailand exemplify this textbook “America First” strategy: they emphasise the need for US firms to clinch sole-source contracts (read: excluding non-American businesses) to develop critical minerals deposits in these countries. A bilateral US-China trade pact would further complicate France’s equation by granting US firms preferential access to Chinese minerals and leaving other G7 countries scrambling to secure supplies.

France still has a card to play: pushing for the establishment of binding production standards for critical minerals produced on G7 soil or used in G7-based supply chains, including via public procurement. Much of the groundwork for this plan already exists: G7 economies called for the creation of such standards under Canada’s G7 presidency in 2025. However, the 2025 edition of their plans foresees these standards being non-binding, meaning they have little chance of being implemented.

The trick for French policymakers will be to frame G7 initiatives not as constraints on American freedom of action, but as force multipliers in global geoeconomic competitions that the US has chosen to fight

France could address this challenge with a proposal to design mandatory standards for critical minerals that are either produced on G7 soil or used in G7 supply chains. Such a plan, put forward by the Think7, would help to reassure the private sector that demand for G7-made (and thus higher-priced) minerals is forthcoming—possibly helping to unlock private investments on G7 soil. If this idea gets traction, a potential next step could be to create G7-managed stockpiles of critical raw minerals, building on US plans to set up such stocks at the domestic level. Whether such proposals would clash with the US deregulation push is an open question, but the French may think this is worth a try.

*

For its G7 presidency, Paris does not need Washington to lead; it merely requires the Americans not to veto. The trick for French policymakers will be to frame G7 initiatives not as constraints on American freedom of action, but as force multipliers in global competitions that the US has already chosen to fight, and in areas where the American G20 presidency could make advances. If the French G7 presidency achieves this, it may—against all odds—find a willing partner in the Trump administration.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.