Health

The pandemic has transformed public health into an arena of geopolitical competition. Some countries will now take a more strategic view of their capacity to produce or acquire medical goods – and will use this as a tool of foreign policy

The pandemic has transformed public health into an arena of geopolitical competition. Some countries will now take a more strategic view of their capacity to produce or acquire medical goods – and will use this as a tool of foreign policy

The first responsibility of a state is to protect the lives and security of its citizens. The covid-19 pandemic brought the public health dimension of this commitment to the forefront of global politics. The virus showed how global interconnectedness through the rapid movement of people could create extraordinary vulnerability to a highly infectious disease. As covid-19 eclipsed all other political concerns and countries engaged in intensifying systemic competition, governments’ approach to public health became a core indicator of their effectiveness. More significantly, the pandemic made clear how countries could exploit the production and distribution of medical goods to gain extraordinary power.

This is true of vaccines above all. The struggle to acquire personal protective equipment (PPE) in spring 2020 was a harbinger of ruthless international competition for medical products. But the development of vaccines offered the first real opportunity to mitigate the threat of covid-19, reduce rates of illness, and allow economic activity to return to normal. This was the first time in history that all governments had a vital interest in procuring a new medical product to administer to every adult in their countries.

With covid-19 almost certain to remain in circulation, and further pandemics likely to occur in the future, health will keep its place as one of the components of national security and power. Countries will now take a more strategic view of their capacity to produce or acquire medical goods. And some will use this capacity as a tool of foreign policy. During the pandemic, countries have sought to benefit from deliveries of medical goods to their partners – to strengthen relations, prevent friendly countries from being at a disadvantage, or gain more direct benefits. In some cases, states have threatened to withhold medical products to further their strategic goals. Most of all, though, powerful countries have sought to secure access to vaccines and other goods, including through restrictions on exports or preferential agreements with suppliers.

At a time when geopolitical competition is overlaid with rivalry between different systemic models, the way that countries have tackled the pandemic has had an impact on their international credibility and prestige. Several factors have determined how many cases and deaths have occurred in different countries, making it difficult to equate success in handling covid-19 with a particular socio-political system (see: Map 4 in the culture essay). Nevertheless, one can observe some patterns and standout individual cases.

Until now, the regions that have fared worst in per capita deaths have been Latin America and eastern and south-eastern Europe (see: Map 1). Those that have been most effective at reducing the impact of the disease are east Asia, south-east Asia, and Australasia. China has been particularly careful to treat its response to covid-19 as a matter of national reputation, limiting investigations into the origin of the virus and often suggesting that it may have reached the country from overseas, as well as trumpeting its success in containing the crisis. But other Asian countries have also done well: the key lesson appears to be about the benefits not of state control but of experience from previous epidemics – of preparedness and responsibility. Trust in the authorities and in medical advice, especially on vaccines, also seems to play a role in some cases (see: Map 2). Death rates in the United States have been high relative to its population density – and have continued to rise even since vaccines have been widely available, due to widespread resistance to taking them. In this way, covid-19 seems to add credibility to the idea that east Asia is rising in influence and the US is declining.

Map 1Download image

Map 2Download image

The production of medical goods is highly concentrated in certain countries – as one would expect from the fact that, prior to the pandemic, most governments treated this almost exclusively as a question of market efficiency. The shift to seeing health as a matter of national security has prompted a rethink, leading some governments to call for production to be brought home or production lines diversified. The European Union’s 2020 New Industrial Strategy for Europe states that “access to medical products and pharmaceuticals is crucial to Europe’s security and autonomy in today’s world”. In April 2020, then US presidential trade adviser Peter Navarro said: “never again should we have to depend on the rest of the world for our central medicines and countermeasures”.

When covid-19 struck, global shortages of PPE meant that some countries were suddenly without the means to safeguard the lives of their healthcare workers and citizens more generally. China dominates the global supply of PPE imported by other advanced economies (see: Map 3). In 2019 the country was the source of 50 per cent of PPE imported by Europe and 47 per cent of PPE imported by the US – including 67 per cent of masks and respirators imported into Europe and 72 per cent of those imported into the US. In the early months of the pandemic, with Hubei province locked down and China desperately seeking PPE for itself, the country’s exports dropped significantly; some manufacturers with plants there said the government had requisitioned their output.

Map 3Download image

As the pandemic spread, other countries imposed export restrictions on PPE, including first some EU member states and then the EU as a whole. The US also imposed export restrictions. After China scaled up production and controlled the virus at home, its PPE exports increased. China used exports and, in particular, donations of masks and other protective equipment as a way to highlight its benevolence: Beijing donated PPE both to countries in need and to those it wanted to impress for strategic purposes, including Ethiopia and Hungary. Recipients of Chinese shipments often made public displays of gratitude for them; Serbia’s president, Aleksandar Vucic, spoke of China’s “brotherly care for the citizens of Serbia”.

The pandemic has also drawn countries’ attention to their potential dependencies in the procurement of other important medical products. The EU has declared active pharmaceuticals ingredients (APIs) to be a strategic area, alongside products such as semiconductors and lithium-ion batteries. China and India have established leading roles in the manufacture of pharmaceuticals – particularly low-cost generic drugs. In 2015 Europe accounted for 24 per cent of global API production by value. Sixty-six per cent of global API production occurred in the Asia-Pacific (principally India and China), 3 per cent in north America, and 7 per cent in the rest of the world. The EU imported 53 per cent of the APIs it used by volume – almost all from China (45 per cent), the US, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, and India.

The US is more import-dependent than Europe, with only 27 per cent of the manufacturers that supply APIs to the US market located within the country as of 2021; by contrast, 25 per cent of these manufacturers are located in the EU, 19 per cent in India, and 13 per cent in China (see: Map 4). For generic drugs, the share of EU and US manufacturing is lower: 29 per cent of manufacturing sites are in India, 27 per cent in the EU, 16 per cent in China, and 13 per cent in the US. It is unclear whether the complex interdependency of pharmaceuticals supply chains will prevent governments from weaponising them, but wealthy countries are carefully assessing their vulnerabilities in this area.

Map 4Download image

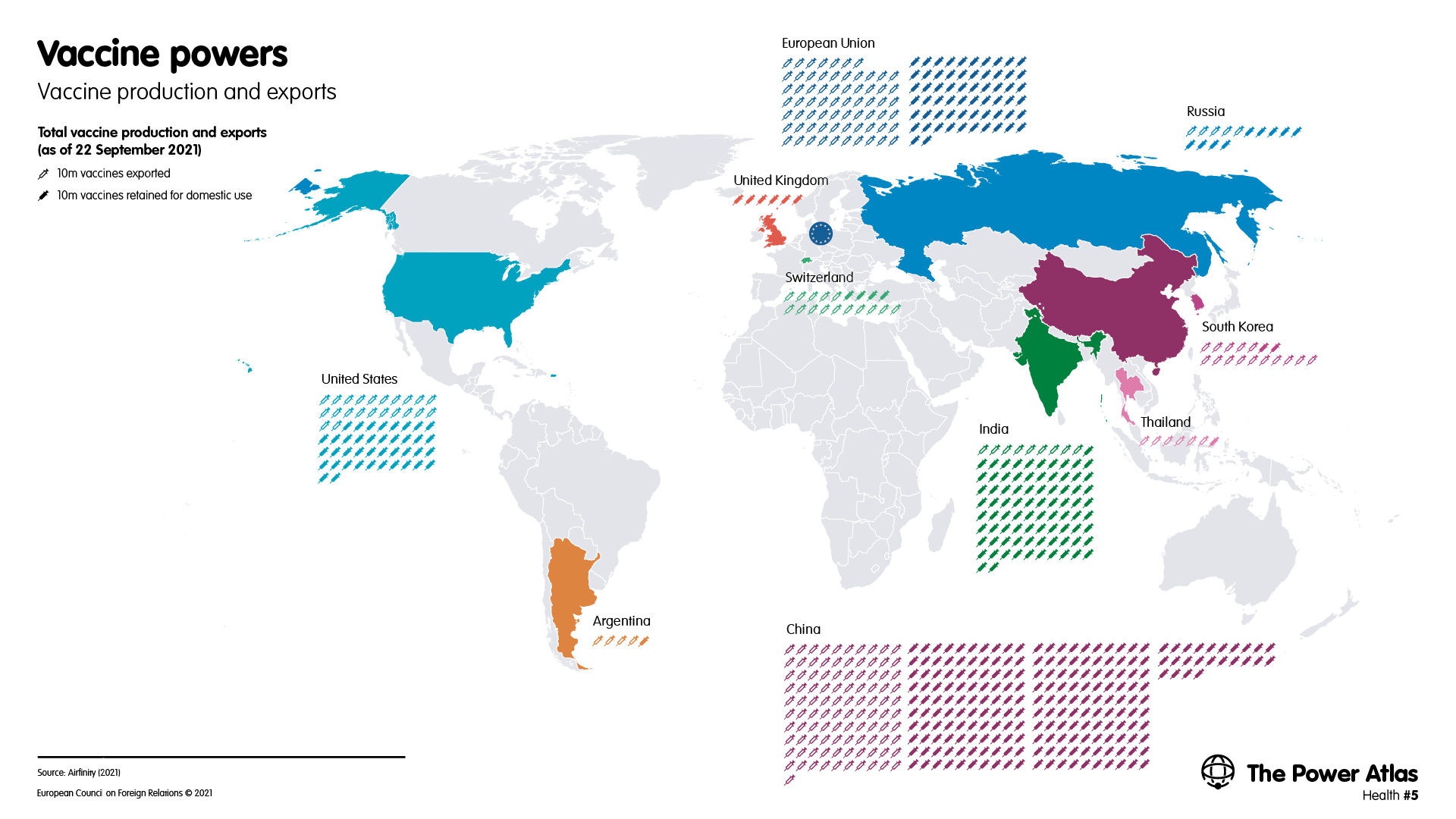

In a normal year, 4 billion vaccine doses are produced worldwide. The development of covid-19 vaccines led to a dramatic increase in vaccine production: it is likely that around 12 billion doses of covid-19 vaccines alone will be produced in 2021. Global vaccine production is dominated by a small group of countries – forming what some scholars have described as a “vaccine club”. A recent study by Bruegel estimates that, before the pandemic, the EU was the world’s largest vaccine producer, closely followed by India. China and the US completed the list of major producers, with significant production also taking place in Indonesia, South Korea, Japan, and Russia. The EU and the US exported mainly to higher-income countries, while India dominated sales to lower-income countries – largely of vaccines produced under licence at low cost. Chinese exports were insignificant.

The advent of covid-19 has radically changed this picture. For covid-19 vaccines, China has vastly increased its production to become the clear global leader, and the US has become the second-largest producer, followed by the EU, India, and the United States (see: Map 5). However, there is a marked difference between the vaccines produced in each country or region: the US and the EU have produced the only mRNA vaccines that have been approved for use – which have emerged as the most effective vaccines against covid-19. The EU and the UK have produced the leading viral vector vaccine, which is based on research at Oxford University and produced by British-Swedish firm AstraZeneca, and is cheaper and more easily transportable than mRNA vaccines. The same technique has been used under contract in India. Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine is also based on viral vector technology. China has focused on producing inactivated virus vaccines, including Sinopharm and Sinovac.

Map 5Download image

In an even more marked change from pre-pandemic patterns, China is now the leader in vaccine exports, followed by the EU. The US and India have exported a smaller number of doses, with the state purchasing the bulk of their production.

There is a significant segmentation of export markets by destination. Producers in the EU have exported a higher proportion of doses to richer countries, while China has exported more to the developing world (see: Map 6). Global patterns of production, procurement, and export reflect a strikingly unequal distribution of vaccines, with Africa and the Middle East particularly disadvantaged (see: Map 7).

Map 6Download image

Map 7Download image

The easiest way to understand the geopolitics of vaccine production and distribution is to compare the different approaches taken by leading powers. One can divide these approaches into the following five categories.

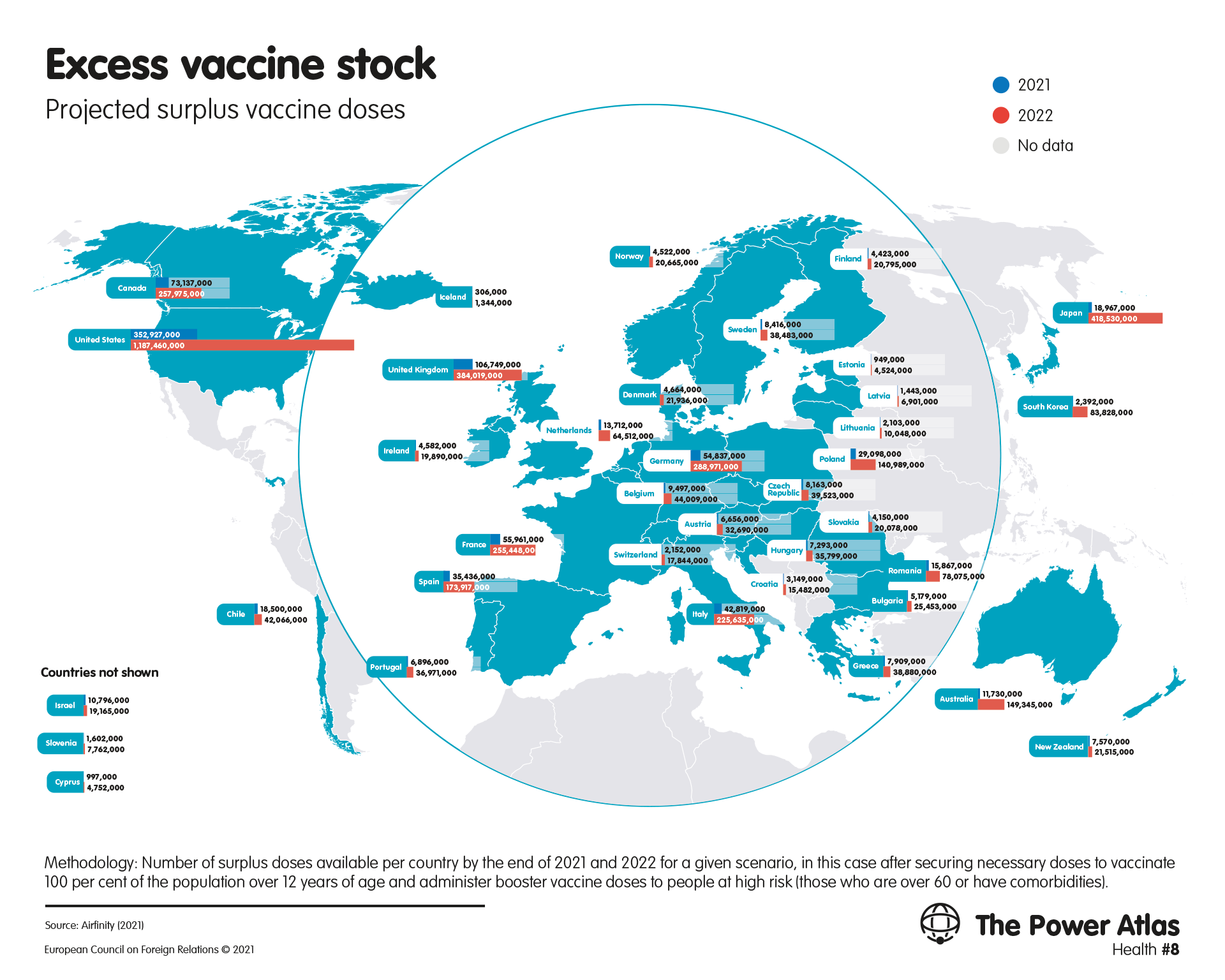

From the beginning of its vaccine effort, the US has followed an industrial strategy designed to address all parts of the production process. In Operation Warp Speed, the US government has invested heavily throughout the vaccine supply chain to rapidly scale up production, and has intervened in the market to promote cooperation between companies. The British government did something similar, working closely with AstraZeneca to develop a production supply chain in the UK for the vaccine developed in Oxford. Both countries used this strategic approach to procure supplies for their own populations, becoming global leaders in the early vaccination of their citizens. The US barely exported any vaccines during the first months of its vaccination drive, but the success of Operation Warp Speed has allowed it to become the leading donor of vaccines to the rest of the world in recent months – and it is poised to distribute many more doses in the next year (see: Map 8).

Map 8Download image

The US has announced that most of its donations will go to the COVAX global distribution mechanism, but it has also directed vaccine donations to its strategic partners: the country sent 2.5m vaccine doses to Taiwan in June 2021 and has also made donations to neighbouring Mexico and Canada (see: Map 9). The US has also promised to fund vaccine donations to the Indo-Pacific as part of a Quad initiative. Through its success in building up what President Joe Biden calls an “arsenal” of the most effective vaccines, the country has established a powerful position to set the terms of the world’s fight against covid-19 – and to offset the reputational damage it has suffered as a result of its domestic response to the virus, which has been hampered by political disputes.

Map 9Download image

Unlike the US, the EU initially approached the procurement of covid-19 vaccines through a traditional arm’s-length process, negotiating contracts with EU-based pharmaceuticals companies and making a relatively small initial outlay of money compared to the US and the UK. As a result, these firms fulfilled their contracts with the EU alongside other contracts, and continued to export doses – primarily to wealthy countries. However, after production problems led to a shortfall in doses, the EU launched an export notification procedure and Italy blocked a shipment of vaccines destined for Australia. In the face of growing public discontent about the slow pace of vaccine deliveries to Europe, the EU shifted towards a more strategic approach. By mid-2021, the bloc had vaccinated large parts of its population and begun to donate doses to third countries. The EU has directed a large part of its donations to its partners in its region, especially in the Western Balkans, as well as to COVAX.

China has had great success in scaling up its vaccine production. And, because it contained covid-19 domestically through stringent restrictive measures, the country has been able to export and donate more than 1 billion vaccine doses (as of late September 2021). China has emerged as the leading supplier of vaccines to the developing world, and has used its sales to advertise its sense of responsibility to address global challenges. The country has also directed exports and donations to areas of strategic interest, including the Western Balkans, and has taken advantage of delays in supplies from the EU. China has focused these exports and donations on its partners in the Belt and Road Initiative. And the country has allegedly threatened to withhold exports for political purposes: in 2021 Ukraine withdrew its support for a statement on Xinjiang at the UN Human Rights Council after Beijing reportedly warned that it could block vaccine exports it had promised to the country.

However, the lower efficacy of Chinese vaccines has undercut China’s diplomatic success. Latin American countries that relied heavily on Chinese vaccines have continued to experience significant death tolls even in the latter stages of their vaccination campaigns. In south-east Asia, countries turned away from Chinese vaccines and towards Western ones after the former fared poorly against the delta variant of covid-19.

Russia bet heavily on its vaccine as a tool of international influence, naming the product after a Soviet-era scientific triumph and promoting its sale around the world. One Russian official said the country planned to vaccinate 10 per cent of the world’s population in 2021. But, so far, Russia’s efforts have fallen far short of its promises. Everywhere from Latin America to south-east Asia, countries that placed orders for Sputnik V have faced massive delays, undercutting Russia’s soft power campaign.

Before the pandemic, India had already established its position as the leading vaccine producer outside the advanced economies – above all through pharmaceuticals giant the Serum Institute of India (SII). As a result, India was able to quickly start producing covid-19 vaccines – particularly the AstraZeneca one – under licence at the SII. By producing this comparatively cheap and easy-to-transport vaccine at a low cost, India aimed to be the pharmacy to the world – it was supposed to supply many of the doses ordered by COVAX. In addition, India began a programme to donate doses to neighbours such as Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar, as part of an effort to build up its regional influence. However, a devastating surge of covid-19 cases at home led India to restrict exports, hitting COVAX and leaving space for Chinese vaccines in the region. Argentina and South Korea are among the other countries with significant contract manufacturing capacity.

The developing world’s lack of vaccine doses has led to an intense debate about the best way to increase global production. South Africa is leading efforts to establish a significant vaccine manufacturing capacity in Africa, a continent that is largely dependent on imports and donations from elsewhere. South Africa and India are at the forefront of a campaign to lift intellectual property protections from medical products related to covid-19. Several firms in South Africa are seeking licensing agreements from Western manufacturers, while two companies in the country have established an mRNA technology transfer hub. The EU has promised €1 billion to build up vaccine manufacturing in Africa. And German firm BioNTech has agreed to manufacture vaccines at sites in Rwanda and Senegal. So far, however, many vaccine production locations outside the developed world merely engage in ‘fill and finish’ operations – processing active ingredients manufactured elsewhere (see: Map 10). This limits the independent power they bring to their host countries.

Map 10Download image

With vaccine production increasing and many people in the rich world vaccinated, a lively debate is under way about how to increase access to vaccines for lower-income countries. Much attention has been paid to vaccine donations, but global health advocates have called for companies to set up production sites in developing countries – or, even better, to transfer technology and expertise to local manufacturers. Such knowledge transfers would not only help increase vaccine production in the medium term but would also begin to redress the unequal distribution of power in global health.

Military

Culture