Economics

Many states now use economic tools to enhance their geopolitical power. If the EU is to become a more capable actor in this new era, it will need to strike a careful balance in its response to the threat of economic coercion.

Many states now use economic tools to enhance their geopolitical power. If the EU is to become a more capable actor in this new era, it will need to strike a careful balance in its response to the threat of economic coercion.

Trade policy once seemed so apolitical that EU member states abandoned their powers in the area and let technocrats in a commission of European experts take decisions for them. The reason they did so was never just because a common trade policy made sense in a customs union and a common internal market. It was also because even powerful countries such as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom could afford to treat tariff negotiations, rules of origin, or trade standards as technical matters in the unidirectional quest for ever more open markets. Had they imagined what a battleground of power this once-technical terrain would become, the European Union might look very different.

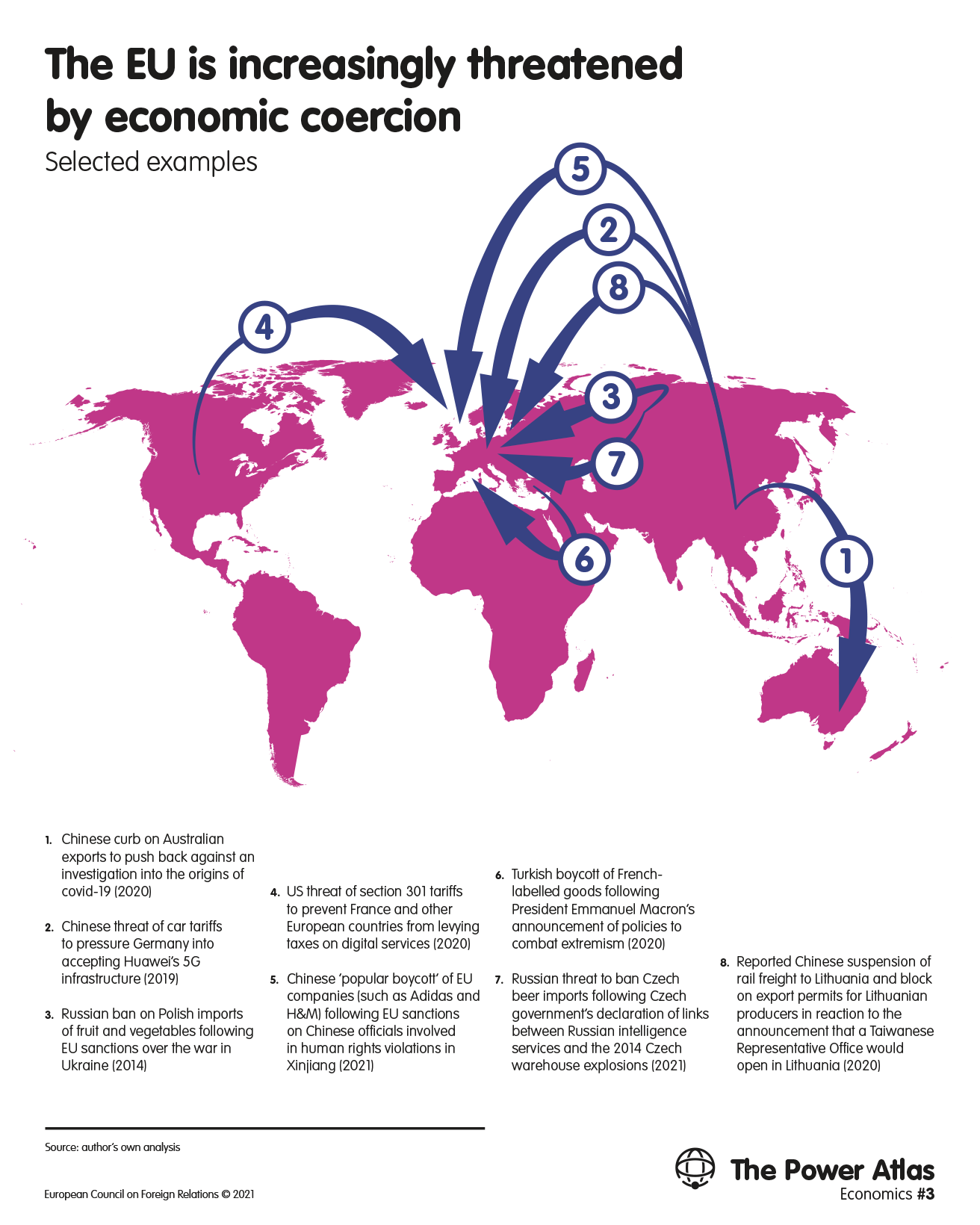

Today, the main battlefield on which great powers compete is not military but economic. It is one on which, for geopolitical reasons, they attach conditions to access to their market and use instruments such as tariffs, quotas, and level playing field penalties, along with tools such as export controls, sanctions, and data regulations. China, Russia, Turkey, and even the United States – Europe’s close ally – have punished other countries for their policy choices or tried to prevent them from making certain choices by pressuring companies to induce behavioural change, and by securing access to ever more sensitive information through the use and threat of tariffs, other curbs on trade, ‘popular boycotts’, financial sanctions, export controls, and forced transfers of sensitive data. China has become a systemic rival of European states, the US, and other liberal democratic countries across the globe. In March 2021, Beijing sent a strong, direct message to Europe when European companies such as H&M and Adidas disappeared from Chinese e-commerce platforms and by manufacturing ‘popular boycotts’ of these firms’ products, an increasingly common Chinese sanctions tactic. The damage was limited, but the message was clear: China is now ready to use economic coercion in direct response to European policy choices – to even moderate EU attempts to adopt stronger policies and close ranks with the US. President Xi Jinping said as much to German Chancellor Angela Merkel. According to Chinese state news agency Xinhua, Europe needed “to make [a] correct judgment independently”, he told her.

But the change in international politics is more profound than any one actor’s attempts at coercion. A wide array of countries increasingly combine state action with geopolitics and economics; they use economic tools to enhance their geopolitical power and geopolitics for economic gain. Their economic weight is increasing relative to that of the G7, which by 2050 will probably account for just 20 per cent of world GDP. The economies of the Emerging 7 (E7) – Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, and Turkey – were 37 per cent of the size of those of the G7 in 1991 (in purchasing power parity terms) but are now a similar size, and might reach 50 per cent of the world’s output by 2040. The E7 are different in many ways; not all of them use economic coercion. But rapid economic growth in these countries – particularly China – is indicative of the rise of a new model of economic statecraft (see: Map 1).

Map 1Download image

Many states now put economics at the centre of a grand strategy combining all instruments of statecraft to enlarge a country’s sphere of influence. Trade deals not only create economic efficiencies but also tie countries to one another through their value chains, while allowing for diversification away from the markets of states with which they have difficult geopolitical relations. Transparent supply chains help states identify pressure points that they can use against their rivals, but also give others the same advantage. A government’s economic threats can alter another actor’s behaviour. Even central bank policies now have significant geopolitical consequences. And the most successful players combine these tools with measures such as development cooperation, language schools, military deployments, or disinformation campaigns – all of which are geared towards gaining strategic leverage over others and securing one’s own position in the world.

The EU’s most important partners – from the US to the United Kingdom and others – have started to react to these developments by enhancing their own geo-economic toolboxes, aiming to strengthen their defences and respond to unfair practices that they were powerless against. Their adaptation – and the irresponsible and dangerous use of economic coercion by former US president Donald Trump – contributed to the emergence of a much more geo-economic era. The change is structural, and the EU needs to deal with it using its own tools.

There are three basic metrics of power and vulnerability on this terrain: offensive capabilities, defensive capabilities, and economic strength.

Offensive capabilities. These include trade agreements, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), punitive tariffs, boycotts, export controls, and personal and financial sanctions, among many other measures. Governments can use such tools to actively pursue policies that increase their economic and geopolitical reach. ‘Positive’ tools of this kind range from trade agreements to investments and connectivity partnerships. During the Trump years, when open international trade came under threat from the EU’s closest partner, the union concluded several trade agreements and advanced its trading power to hedge against deteriorating transatlantic trade relations. The EU also enlarged its networks of trade and common standards through closer partnerships with Japan, Mercosur, and others. China and 14 other Asian countries moved to reduce US influence by concluding the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership – which, in contrast to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, excluded America. China’s SOEs are also a positive offensive tool in that they have negative and, at times, dangerous consequences for Europeans. China increasingly uses SOEs in its strategic quest to dominate markets and marginalise its Western competitors’ industries and capabilities. Heavily subsidised SOEs sell products, or instruct companies they have acquired to sell products, at below production cost – sacrificing short-term economic success for long-term influence (see: Map 2).

Map 2Download image

In contrast, the ‘negative’ offensive tools that states use are designed to exert pressure on other countries and punish them for their conduct (see: Map 3). In 2018 the US administration imposed a 25 per cent tariff on imported steel and a 10 per cent tariff on imported aluminium, labelling the EU’s and others’ steel and aluminium exports as a threat to US national security (a label that remains in place, despite the compromise America and Europe reached in late October 2021). Since 2018, the administration has also prohibited Europeans from trading with Iran. In 2020 China curbed 10 per cent of Australian exports as punishment for Australia’s call for independent investigations into the origins of covid-19. In late 2019 Beijing used the threat of car tariffs to try to pressure Berlin into accepting a Huawei bid to build Germany’s 5G infrastructure – a core decision about the country’s future critical infrastructure and security. In late 2020 President Recep Tayyip Erdogan called on Turks to boycott French-labelled goods after his French counterpart, Emmanuel Macron, announced new policies to combat extremism. Moscow banned in 2014 the import of a vast array of EU agricultural products, especially those produced by Poland, in response to Western sanctions on Russia over the war in Ukraine. While these actions were geopolitically motivated, Russia justified them by pointing to public health concerns. Russia threatened in May 2021 to ban Czech beer imports after the Czech government declared that the Russian intelligence services were likely responsible for explosions at a Czech warehouse in 2014.

Map 3Download image

Defensive capabilities. These are designed to limit a country’s vulnerability when confronted with negative offensive economic instruments. Sometimes, of course, the best defence is a good offence: agreements that diversify trade relations can reduce the overexposure of certain sectors, for instance. But the rise of economic coercion in recent years has prompted many powers, including the EU, to adopt robust defences. Europe has updated its trade enforcement regulation to allow it to act in trade matters even if there is no final ruling by the World Trade Organization (due to blockages in the institution caused by the Trump administration’s refusal to appoint new members to its appellate body). The EU has also implemented an investment screening mechanism that allows it to intervene when foreign companies acquire European firms mainly for geopolitical reasons. The EU is currently updating its competition policy to impose fines on SOEs or heavily subsidised foreign companies that can act in unprofitable but strategic ways in the EU market. The US, China, and others have put in place a vast range of deterrent measures that, when they are subject to economic coercion, allow them to sanction third-country companies or impose broad and heavy trade restrictions on the grounds of national security (many explicitly state that they have this capability; others only hint at it). The US now has an ‘integrated deterrence’ doctrine that uses economic measures as part of its national defence strategy.

Like offensive measures, these defensive capabilities resemble those in other areas of foreign policy. What would be diplomatic initiatives or even military strikes in traditional statecraft can now be free trade agreements or sanctions in the economic sphere (see: Map 4). What are regional security architectures, arms control treaties, or military deterrents in traditional statecraft can be agreements or instruments designed to uphold WTO rulings when the global trading system comes under pressure.

Map 4Download image

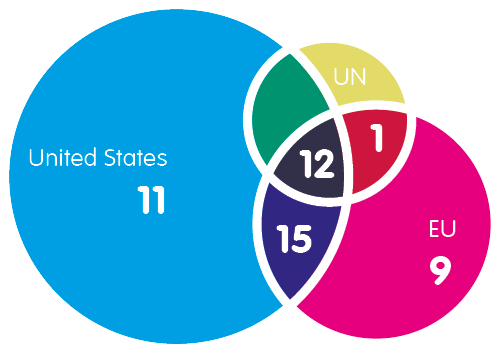

Sanctions

List of sanctions programmes (2021)

US Sanctions - 11

EU and US and UN Sanctions - 12

EU and US Sanctions - 15

EU Sanctions - 9

EU and UN Sanctions - 1

Economic strength. This metric is different from the other two. In the military realm, armament and the strength of weapons systems directly determine the power of offensive and defensive capabilities; the establishment or use of offensive or defensive tools does not typically compromise a state’s strength. But it does in economics. Here, the use of defensive tools (and some offensive tools) often involves state interventions in economic processes, and can involve protectionism. Protectionism tends to stifle innovation, limit competitiveness, and render a market unattractive for businesses – all effects that might result from a state’s efforts to prop up SOEs, implement punitive tariffs, or develop deterrents or instruments to impose countermeasures.

However, in the geo-economic era, states’ efforts to enhance their economic strength are the basis of success. Pressuring an economically strong and interconnected country can be costly for the coercer. This is not least because the coercer will have to account for the dependencies and asymmetries that the strong country could exploit in retaliation. This means that European countries and many other states need to walk a fine line in enhancing their offensive and defensive capabilities, all while avoiding negative repercussions for their economic strength. China has expanded domestic demand, fostered innovation, and reduced its reliance on foreign markets, while still integrating ever more international trade into its supply chains. This strategy is difficult to implement but has had great success – and has, as discussed, proven dangerous for others.

These three basic metrics are not, by themselves, sufficient to explain the power dynamics of geo-economics. States use increasingly advanced forms of economic coercion to achieve their strategic goals, often attempting to alter a government’s policies by targeting companies rather than the government directly. These forms of coercion function through central hubs in economic networks, at which third countries can exploit foreign firms’ need for access – as analysts Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman first revealed.

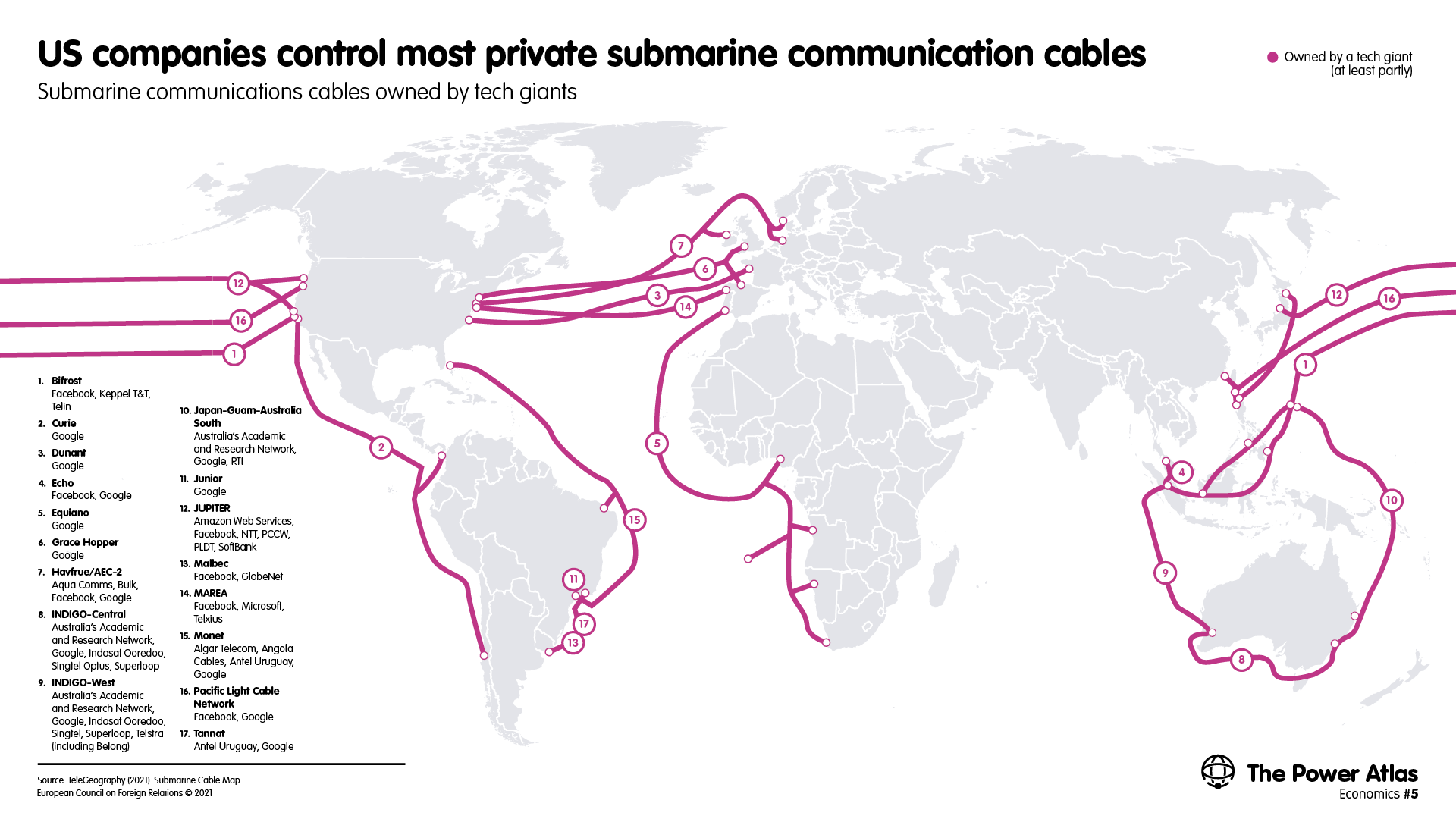

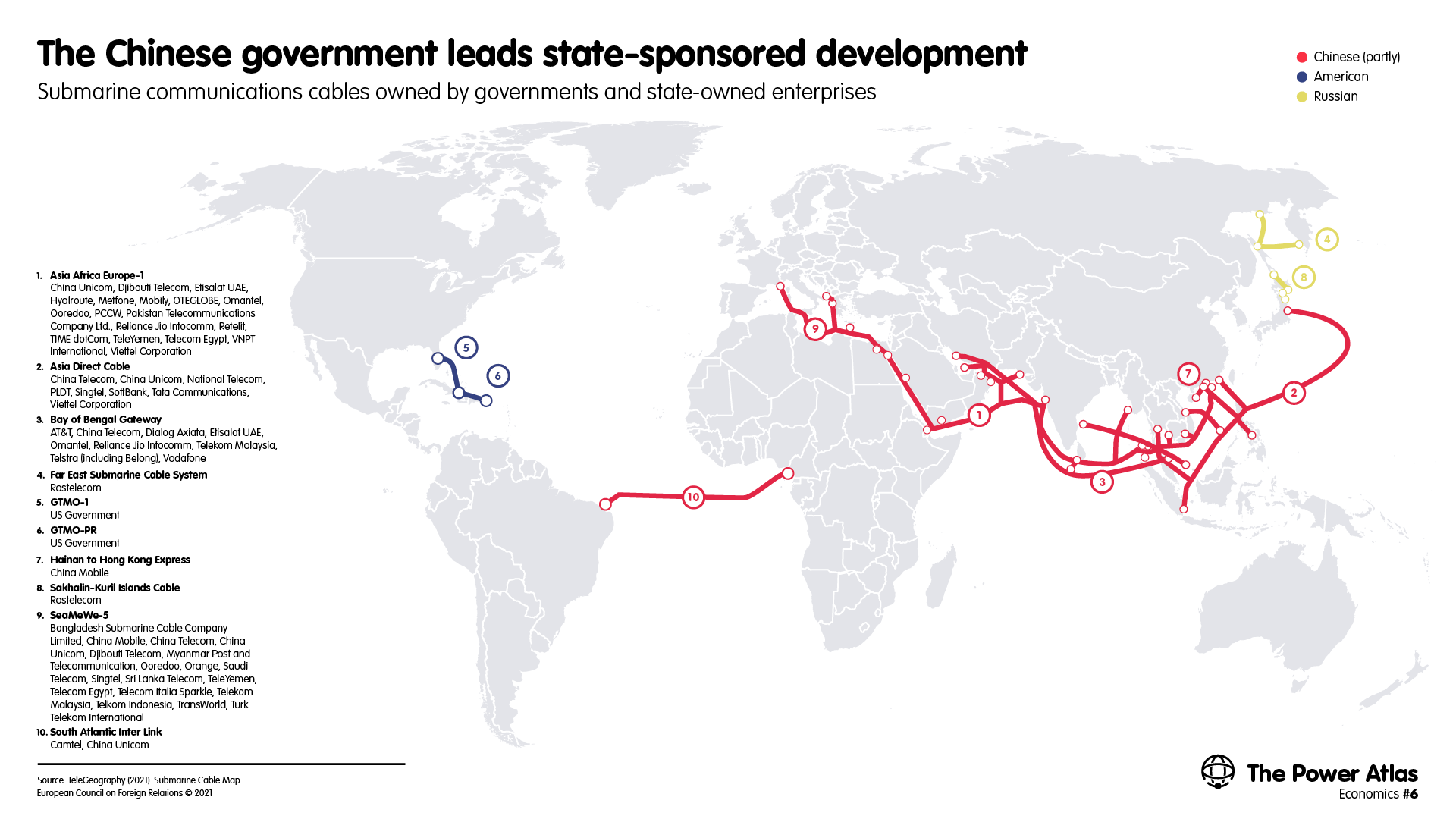

It used to be that Europeans thought of critical infrastructure primarily in terms of assets such as water or nuclear plants (see: Maps 5 and 6). But, in a globalised economy characterised by geo-economic competition, an important technology or centralised point of exchange can also take on the role of critical infrastructure – the disruption of which is detrimental to a company, an entire sector, or the economy as a whole. Powerful countries can now make use of critical financial and informational choke-points. And China and America are in an intensifying race to secure, defend, and increase their control over these choke-points. When they tell businesses and third countries to behave in a certain way or else risk exclusion, the EU sometimes calls this “extraterritorial reach”. But it too often thinks of this in terms of US extraterritorial sanctions and not as a structural development in how economic coercion functions – and that China can increasingly exploit.

Map 5Download image

Map 6Download image

The Clearing House Interbank Payments System, for example, is responsible for 95 per cent of all US dollar settlement, clearing and settling $1.8 trillion in domestic and international payments per day. Moreover, 95 per cent of top banks worldwide are members of the SWIFT messaging system and use it for transactions. Washington can de facto deny banks and companies access to these choke-points, and can use the threat of doing so to coerce them to behave in ways that align with US strategic goals – even against its European allies’ explicit will. The US clearly dominates the global financial system (see: Map 7). Europeans and many others depend heavily on American banks’ financial services, particularly investment banks. For example, the EU depends on US-controlled payment systems, notably Visa and Mastercard. These types of dependencies give US primary sanctions great reach beyond America’s borders, and make it significantly more difficult for other states to maintain financial channels outside US control.

Map 7Download image

The US dominates international finance

Investment banking market value by region, $bn (2020)

Meanwhile, China has created a digital renminbi that is projected to account for 15 per cent of all Chinese electronic payments by 2031 – and that, in theory, could create alternatives to the dollar-dominated financial system (even if that currently seems unlikely). Chinese payment systems are increasing their reach and are becoming an ever more important choke-point (see: Maps 8 and 9).

Map 8Download image

Great powers are also racing for control over and access to other choke-points, such as internet exchange points. And Chinese scholars have identified several areas in which China could soon have control over choke-points of advanced technology such as high-performance computers, quantum communications systems, core chips, and satellite navigation and operating systems.

To gain influence, isolate a country, or make sure another state does not get access to information or goods, great powers increasingly impose new regulations on companies – or ‘squeezing laws’. These include obligations, prohibition of compliance with other countries’ laws, and licensing requirements for a growing number of goods and services. China’s newly adopted extraterritorial export controls, anti-sanctions law, and blocking statute are examples of this. If European firms follow obligations they have in the US or the EU, they may have to ask Beijing’s permission to export certain goods or services, face punishment, or even give up on doing business in China.

The systemic rivalry between the US and China – particularly Beijing’s approach to it – is leading democracies and former advocates of free trade to change course. Under Trump, the US employed methods that accelerated a shift in the international system towards fierce geo-economic warfare, even using its leverage against its traditional allies. The new administration in Washington has abandoned this approach to its allies and is actively rebuilding relations with them, but the fundamental power dynamics of geo-economic warfare will not change.

In fact, the Biden administration is not changing the US posture overall or returning to the liberal globalisation of the 1990s and 2000s. It is merely replacing negative offensive tools that sometimes culminated in ‘maximum pressure’ policies with positive offensive tools or ‘extreme competition’. This approach emphasises investment in US economic strength and efforts to multiply that strength through close relations with democracies across the globe. The US-EU deal on aluminium and steel tariffs underscores this point: the Biden administration recognises that it is a fundamental US interest to find a compromise with Europeans but, fundamentally, European exports still represent a national security threat from the administration’s point of view. The Biden administration wants the US and its democratic allies to create a strong bulwark against third-country coercion, and to counter third-country offensive policies in markets in Africa and other regions (particularly those affected by China’s Belt and Road Initiative) through offensive policies such as infrastructure and connectivity partnerships. But it is not easing trade tensions with Europe out of a belief that the geo-economic era has ended and the world is returning to a trading system that is governed by rules that everyone will abide by.

Domestically, Biden passed a $1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus package and is making investments in infrastructure and human capital on an unprecedented scale – which, in the long term, could increase the strength of the American economy to a new level. Some experts have said that this effort could even lift the US economy above its steady state and revolutionise economics. The US now emphasises positive offensive measures in the geo-economic competition between great powers, but the Biden administration has yet to define how it will use its impressive arsenal of economic coercion instruments, particularly against China, Russia, and other authoritarian regimes. The administration has upheld Trump-era punitive tariffs on China, but has not escalated them. It is entirely possible that the administration will revert to these tools much more towards the end of Biden’s presidential term – either because a Republican-dominated Congress pushes the administration to be more assertive in these ways, or because the administration believes that outcompeting China might be a smart long-term strategy but does not yield the short-term results it needs to prove it is sufficiently tough on Beijing.

Europe has several disadvantages in the geo-economic era. The EU has the most globally connected of markets. And both superpowers are interested in access to that market and in good relations with the EU. But the European Commission was never conceived of as a mechanism to engage in geo-economic statecraft or implement a positive offensive strategy (even if it has performed relatively well in some areas of this). Europe also struggles to build up its economic strength and develop effective defensive instruments. This is due to its odd institutional structure – which is split between supranational institutions and member states – as well as divisions between member states and its complex and slow decision-making processes.

On economic strength, Europeans struggle to match the investments and ambitious reforms the Biden administration is implementing in the US. The NextGenerationEU recovery plan does not provide the same kind of firepower as its US counterpart (even if the US has embarked on a great experiment that is not certain to increase its economic strength efficiently). To change this, Europeans would have to view the single market as much more of a geo-economic asset. Completing the single market would make the EU more competitive and reduce its vulnerability to economic coercion. The same applies to strengthening the euro. Too often, Europeans become stuck in debates about the technicalities of a capital markets union or a digital single market.

On defensive instruments, the EU suffers from its exceptional institutional shape. Its system of foreign direct investment screening is impressive on paper, but it is unclear whether all member states will implement it with the necessary rigour. For now, the EU lacks the legal provisions needed to counter many forms of economic coercion. This is why the EU should establish an anti-coercion trade instrument.

The European Commission will soon propose such an instrument that could make countermeasures possible. This will require member states to overcome their understandable hesitation about it – which might be partly a remnant of the easy globalisation of recent decades – and to simultaneously avoid protectionist policies that could reduce their economic strength. But, if they strike a careful balance and establish the instrument, the EU will become a much more capable actor in the geo-economic era.

Main essay

Technology