Culture

Cultural norms have a huge influence on states’ ability to use their power resources. In a multipolar world of ideas, any universalist project is likely to provoke a backlash more powerful than the force that provoked it

Cultural norms have a huge influence on states’ ability to use their power resources. In a multipolar world of ideas, any universalist project is likely to provoke a backlash more powerful than the force that provoked it

At the end of the cold war, the world experienced a unipolar moment. It was not just that the West had won the global arms race: liberal democracy became the gold standard, while Western culture, ideas, and values were pre-eminent. But the cultural dynamics of the 2020s are very different. The world is moving from an imperial era – in which Western countries saw their ideas and values spread to the most distant corners of the globe, empowered by the success of the capitalist economic model and a revolution in communications technology – to one of decolonisation, in which countries are increasingly trying to ‘take back control’ and consume their own culture rather than mimic others.

The onset of this new era, marked by the cult of one’s uniqueness, has dramatic implications for the exercise of power in the world. There are at least three big new trends for the power of culture: a mood of cultural decolonisation that halts the spread of Western ideas, a transformation of democracy that challenges liberalism, and a shift from relying on the power of example to exploiting the vulnerabilities of other systems. To grasp how these dynamics have created a new balance of cultural power in the world, it is important to understand where they come from and how the idea of culture has changed in the last three decades.

Just before the end of the cold war, America was captured by a fear of inevitable decline triggered in part by the rise of Japan. It was in this context that political scientist Joseph Nye argued that the debate about how to influence others focused too much on “hard power” – the economic and military muscle of the state – and not enough on the attractiveness of the ideas and cultures of different societies. The capacity to attract, which he christened “soft power”, made him sceptical of the arguments of those who predicted America’s decline. Nye argued that the United States had hidden reserves of soft power based on its liberal model, which the rest of the world would want to imitate.

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, the idea of soft power seemed to explain everything. It explained why Soviet communism had collapsed, why democracy had spread globally, and why the post-cold war world was dominated by the US. There was a sense that the ‘end of history’ was not only a political phenomenon but a way of life that encompassed all aspects of one’s being. It was also a missionary era, an ‘age of conversion’: alongside the advance of liberal democracy and American consumerism, there was the spread of religions that always had this universal appeal – Christianity and other faiths trying to disseminate their ideas, Saudi Arabia dispatching its imams to other countries, and so on (although some would see the spread of Islamism as the first big indicator of resistance to Western soft power).

But the age of conversion created fear of what the French philosopher René Girard has called “contagious similarity”. He claimed that the spread of ideas could generate anxiety in many countries about a “pure and simple disappearance of their society”. Today, American soft power is not so much a virus that is close to taking over the world as one that has prompted the emergence of very powerful cultural antibodies. And, in many countries, these antibodies are much more powerful than the universalist ideas that were meant to trigger them.

There is now a celebration of cultural resistance in various forms rather than attempts to mimic the West. Multiple ideologies are doing well – we no longer live in the flat world of transnational ideologies but rather one characterised by the spread of ideas that preserve people’s cultural essence. The digital revolution has accelerated all this by making it easier for diasporas to maintain their national cultures. It has also allowed a shift from a verbal to a non-verbal culture that is starting to dethrone the central position of the English language. In the new visual world, one does not need to speak English to become a global celebrity.

This is leading to a new map of world power that has three important dynamics.

Towards the end of the cold war, the spread of American values was widely seen as being synonymous with freedom. But, today, many in the world regard liberty as coming from a rejection of universalist values rather than an embrace of them.

This is leading to a new map of world power on which the most important cultural powers are not the universalists (the flat-worlders) but unique cultures that are hard to replicate and, therefore, provide novelty without threatening the culture of the consuming nations. Indian cinema, Turkish television shows, and South Korean pop music – all things that do not threaten to take over one’s society – have become more attractive than Hollywood or American pop music.

Bollywood is one example of this. As Map 1 shows, India produces more movies than any other country in the world. In 2019 India produced 2,446 movies to China’s 1,037 and the United States’ 601. In the 1990s, the US was by far the biggest film producer. India exports its films to more than 70 countries.1 Indian cinema has spread to countries with no direct links with India – such as Nigeria, Egypt, and Peru – because it allows people to be entertained “without engaging with the heavy ideological load of ‘becoming Western’”, as anthropologist Brian Larkin puts it.2

Map 1Download image

A huge domestic market partly explains India’s rise to cultural prominence, but does not explain that of some of the other new cultural superpowers. One of the most surprising is South Korea, a country that is increasingly punching above its weight in the cultural stakes.

In 2020 South Korean movie ‘Parasite’ became the first non-English language film to win ‘best picture’ at the Oscars. So-called K-dramas have been dubbed into many indigenous languages such as Guarani and have captured 86 per cent of television viewership in, for example, Iran. And South Korean video games have become incredibly popular around the world.3 But the most surprising South Korean export is perhaps pop music. K-pop is now a global phenomenon that is challenging the dominance of American and British music.

In 2012 South Korean pop song ‘Gangnam Style’ had the first video in history to reach one billion views on YouTube.

In July 2020, K-pop boy band BTS broke the record for most number-one singles on iTunes worldwide, which had previously been held by Adele. The group’s track ‘Black Swan’ topped the charts in 104 countries. In 2020, as Map 2 shows, BTS singer V broke the record again with his song ‘Sweet Night’, which topped the iTunes chart in 118 countries. The band has also become Guinness World Record holder for most Twitter ‘engagements’.

Map 2Download image

Turkish television shows have spread almost as far as South Korean pop. Programmes such as ‘Magnificent Century’ have come to rival American television in international popularity, sweeping through the Middle East, Asia, and Latin America. Known as ‘dizi’, Turkish period dramas seem to have “achieved the perfect balance between secular modernity and middle class conservatism”, according to author Fatima Bhutto.4 Since 2002, more than 150 dizi have been sold to over 100 countries, including Algeria, Morocco, and Bulgaria. It was ‘Magnificent Century’ – which was sold to 89 countries (see: Map 3) – that blazed the way for others to follow. The Turkish government claims that, by 2023, the Turkish economy will pull in $1 billion from dizi exports.5

Map 3Download image

During the cold war, the world was split between free countries and authoritarian states – a divide that gave enormous soft power to the West. It was not just that many people yearned for the freedoms of liberal democracy, but also that liberal democracies seemed to be richer and better at solving political problems than their rivals. And, in the case of the US, they were also more powerful in every measure.

Superficially, the world looks very similar today, with many people talking about a new cold war between the US (as the ‘leader of the free world’) and a China that stands alongside other authoritarian powers such as Russia. However, although maps of the politics of the world might be superficially similar, the power of political ideals has changed dramatically. There are two profound differences between the world today and that of earlier eras.

The first concerns the performance of democracies. When it comes to the big questions on the political agenda, there is no longer a clear link in popular perceptions between regime type and effectiveness.

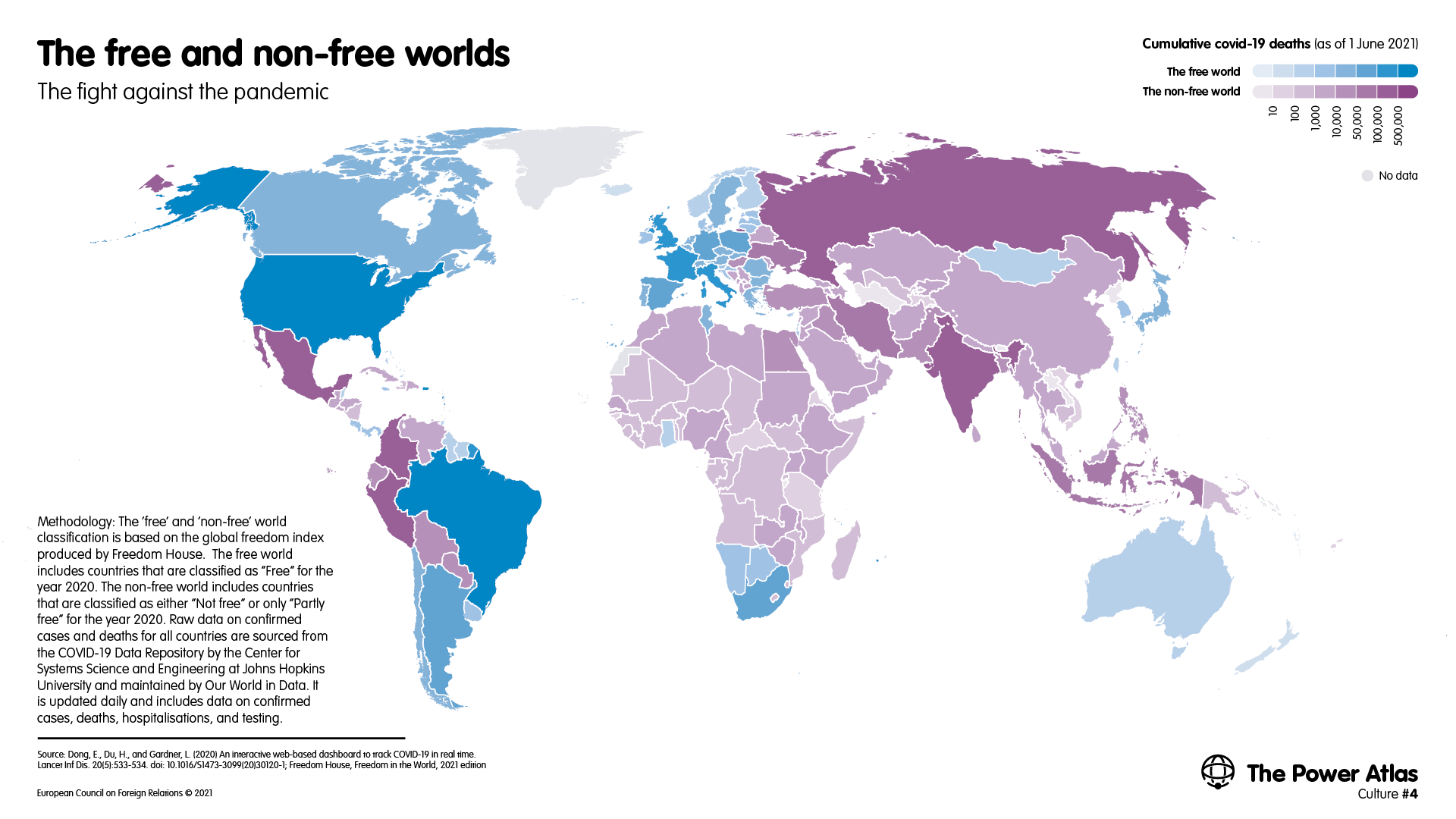

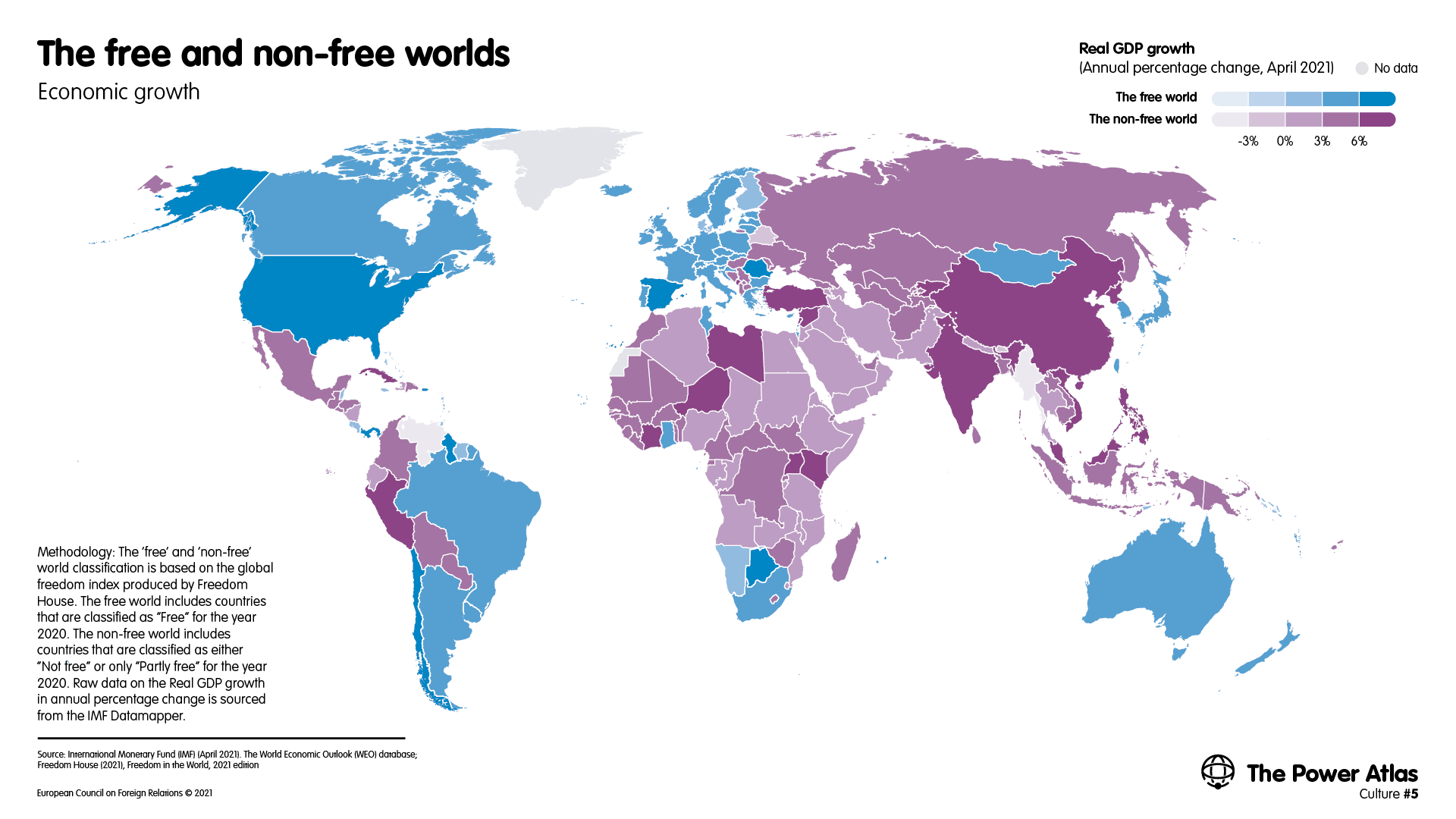

As Map 4 shows, there does not seem to be a big difference between the success of the free and non-free countries when it comes to the battle against covid-19. And Map 5 shows that there is a similar dynamic when it comes to economic growth.

Map 4Download image

Map 5Download image

Map 6 shows that many people believe the link between democracy and power is also breaking. Even in the liberal democracies of western Europe, a majority think that China will overtake the US to become the most powerful country in the world.

Map 6Download image

But even more important than the relative performance of democracies and authoritarian states is a revolution within the idea of democracy. After a long period where liberal democracy seemed to be spreading, there are now reports of a democratic recession and a debate about democratic backsliding. According to Freedom House, the number of liberal democracies grew from around 100 to close to 150 between the 1980s and the mid-2010s. In its latest report, Freedom House talks about “the 15th consecutive year of decline in global freedom” and explains that “the countries experiencing deterioration outnumbered those with improvements by the largest margin recorded since the negative trend began in 2006”.

Map 7 uses Freedom House data to show how the world is no longer split between free and non-free countries. Looking at the work of these authors, we think that we could include a new category, ‘born-again authoritarians’, to describe states that had a taste of freedom but then moved towards the non-free world. Examples of this are Hungary, which has been classified as “partly free” since 2018, and Russia, which has been classified as “not free” since 2004. More recently, India moved from being “free” to being “partly free” due to a multi-year pattern of discrimination against its Muslim population and attempts to silence critical voices in the media and civil society. What comes out of this map is a much more contested idea of what democracy is – something that makes a simple opposition between the free and non-free worlds very difficult to use to mobilise political support.

Map 7Download image

This is not simply because many of the born-again authoritarians still claim democratic credentials, as is the case in many countries where they have won free, if not always fair, elections. It is also because – as a recent study conducted by Pew Research Center demonstrated – the vast majority of American and French voters are deeply disappointed with their own political systems (as are many others in Europe). Some are even unconvinced that they still live in a democracy. Map 8 shows that a surprising number of people around the world think that military rule is a good way of governing a country. In the US, for example, 20 per cent think along those lines. In the European Union, Romania has the biggest share (31 per cent) of potential supporters of military rule.

Map 8Download image

The most dramatic change to the missionary era is that great powers now seem keener to exploit the weakness of other systems than to strive to become a model themselves. Authoritarian states such as Russia find it much easier to exploit the weaknesses of others than to export their own values or political models. They can see how they can increase their power by dividing others without needing to come up with anything that is attractive on their own side.

In many advanced democracies, the political centre is eroding, and societies are becoming polarised into camps that are divided by culture and values. The stark polarisation of society in many countries with advanced economies has created a lot of vulnerabilities to external interference. Map 9 shows how divided the world now is, using the V-Dem indicator of polarisation in society. The indicator is based on ratings provided by experts and academics in each country, who measure differences of opinions on major political issues.

Map 9Download image

The front line in many of these new conflicts is often culture and identity rather than class. And the issues that are most divisive often relate to sexuality. Map 10 shows a profound gap between young and old people in different countries. Often, it is when countries have begun to liberalise their attitudes to these social questions that the previous majorities begin to feel that they might become ‘strangers in their own lands’ – and to organise politically. The Brexit referendum and the rise of Donald Trump have both been linked with the idea of these ‘threatened majorities’ fighting back against cultural liberalisation.

Map 10Download image

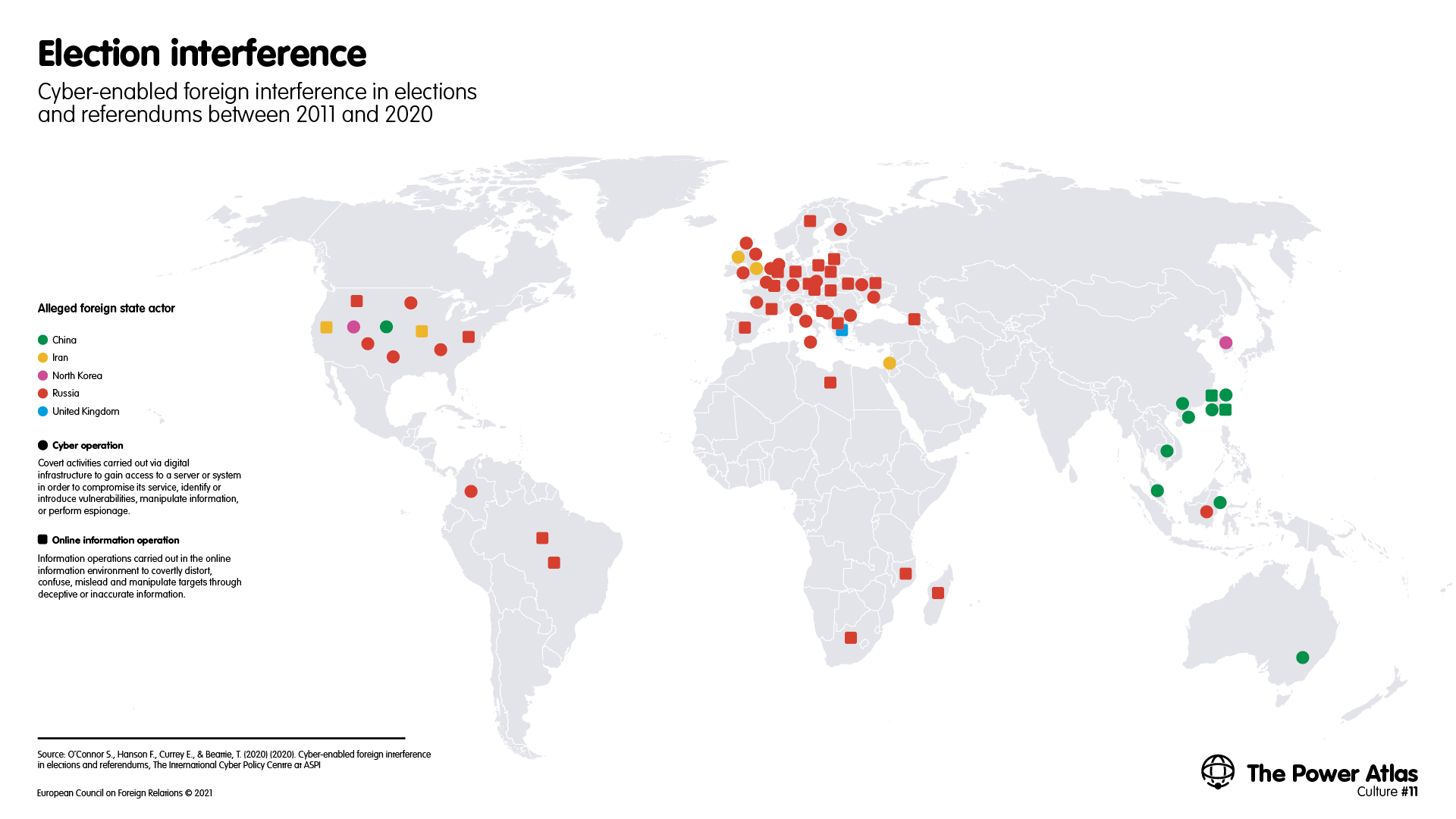

Both the Brexit referendum and the election of Trump were also subject to debates about foreign interference. And the rise of social media has made it easy for external powers to change domestic debates. From foreign troll factories to Twitter bots and Cambridge Analytica, the role of foreign powers in shaping national debates has become one of the most talked-about topics of the modern era. Map 11 shows that, between 2014 and 2020, foreign powers attempted to interfere in 33 elections collectively involving 1.7 billion people. Map 12 indicates that the cumulative effect of all these trends is a collapse in faith in democracy – making societies more vulnerable to this kind of external manipulation.

Map 11Download image

Map 12Download image

As the world moves from flat universalism to cultural protectionism, many countries are more defined by the cultural antibodies that developed in resistance to Western soft power than the cultural flows that they were responding to. In the new world, the core divide is not between democracy and authoritarianism but between dependence and independence. States that want to prosper will need to find a ‘sovereignty-friendly’ idea of soft power.

Many people believe the future will be defined by a clash between the West on one side and China on the other, in the same pattern as during the cold war. But, in reality, there is a huge difference between eras – at least so far.

Both the Soviet Union and the US were universalist powers rooted in the tradition of the Enlightenment. They were missionaries who wanted to remake the world in their image.

But China’s pitch to the world has been very different. The claim to power of Chinese culture comes not from the idea that it is a model that should be emulated but rather that China is creating a harmonious environment in which everyone can preserve their indigenous identities in the face of American or Western expansionism. In that sense, Chinese soft power has been a resistance identity rather than a missionary one. And, in this world of cultural resistance, “merchant powers” will be more effective than “missionary powers” at finding global followers. Unlike the missionary, the merchant pretends that she does not want to change or convert you. It is her focus on your self-interest that will make the merchant more acceptable than the missionary.

Paradoxically, in this new geopolitical polarisation, the biggest threat to Chinese soft power would be to present it as a model to the world. Upgrading the Chinese Dream into an alternative to the American Dream would make it less attractive.

This culture essay was supported by

[1] Fatima Bhutto, New Kings of the World: Dispatches from Bollywood, Dizi, and K-Pop, Chapter 1.

[2] Raminder Kaur and Ajay Sinha (eds), Bollyworld: Popular Indian Cinema Through a Transnational Lens, p. 21.

[3] Bhutto, New Kings of the World, p. 163.

[4] Bhutto, New Kings of the World, p. 116.

[5] Bhutto, New Kings of the World, p. 158.

Health

Back to home