Strengthening European autonomy across MENA

Turmoil in the Middle East and north Africa directly affects Europeans. Yet their influence in the region has never been weaker. The region has been in flux since the wave of Arab uprisings began in 2011, experiencing revolutionary movements, the end and reassertion of authoritarian rule, and repeated attempts by established elites to crack down on agents of change. Despite its considerable economic and political partnerships with regional players, Europe has been unable to influence the major shifts that have taken place. This failure has often come at a high cost for Europeans.

Today, civil wars rage in Libya, Syria, and Yemen. The central authorities look increasingly shaky in several other countries too. Popular discontent has provoked large-scale public protests in Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Sudan – and it simmers elsewhere in the region. The Middle East and north Africa appear destined for further discord and upheaval in the coming years – reflecting the core reality that the political, economic, and social drivers of the 2011 uprisings remain as strong as ever. Meanwhile, the upheaval has created openings for increased external interference and fed the forces of extremism and destabilisation.

The European Union and, in any coordinated fashion, its member states are today essentially nowhere to be seen on the series of interlinked regional crises that have such a powerful impact on their interests. Chief among these has been the displacement of millions of people seeking protection from violent conflict, many of whom have sought refuge in Europe. This has been accompanied by terrorist operations across European cities carried out by the Islamic State group (ISIS), an organisation that grew out of conflict and state collapse in Syria and Iraq. Together, these factors have contributed to the rise of populist nationalist parties that have shaken the foundations of Europe’s political systems.

With the region in desperate need of a stabilising and reforming influence, and the United States increasingly uninterested in involving itself in the region’s problems, one might have expected the EU and its member states to take up a prominent role in support of these twin objectives. However, across the region’s many flashpoints, Europeans are largely bystanders – with the Syrian war a prime example of this.

In the limited instances in which it has engaged with the MENA region, the EU has focused on short-term, transactional policies designed to address the migration crisis and the threat from terrorism rather than the underlying causes of instability. Here, the bloc has primarily addressed its concerns through the externalisation of European border control – exemplified by deals with Turkey and Libya that essentially pay local authorities to prevent refugees from crossing into Europe – and limited participation in anti-ISIS military efforts. Some of these arrangements are not only highly questionable from the human rights and refugee law perspectives but are also unsustainable, given that they fail to address the core drivers of regional instability.

Meanwhile, Europe’s one regional success story, the nuclear agreement with Iran, has morphed into a failure. Europe’s response to the United States’ withdrawal from the agreement and its “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran has failed to muster the necessary political capital and economic resources to fulfil European commitments to sustain Iranian compliance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Even in north Africa, where Europe has stronger influence by virtue of economic ties, Europeans undermine their own position by focusing on short-term concerns and on technocratic fixes that lack local support. Europe’s apparent inability to find a mutually beneficial way of working with countries in north Africa – and those elsewhere in the region – has been accentuated by other powers’ growing interest in the region. These powers have provided MENA states with an opportunity to diversify relationships away from their traditional European partners. The EU’s reluctance to engage in deeper or more sustained political involvement in the region has allowed Russia – as well as powers such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates – greater freedom to strengthen their alliances. Unless they adjust, Europeans will become increasingly irrelevant.

Strengthening EU leverage in the MENA region

This project maps Europe’s influence across the Middle East and north Africa, making the case that it should take on a greater role to protect its core interests. Some European officials will likely argue that the EU and its member states have done enough to address the challenges of migration and terrorism, given the bloc’s structural deficits. Yet this would be to underestimate Europeans’ potential influence in the region and the risks that a largely hands-off approach poses.

The project has three main components. Firstly, it maps and quantifies European tools of influence across the MENA region – covering political, military, and economic capabilities – in a series of interactive data visualisations. Secondly, it includes 12 essays on European regional influence, written by experts from key states in the MENA region and beyond. Finally, it sets out the views of MENA officials and experts from all 28 EU member states on European assets and ambitions.

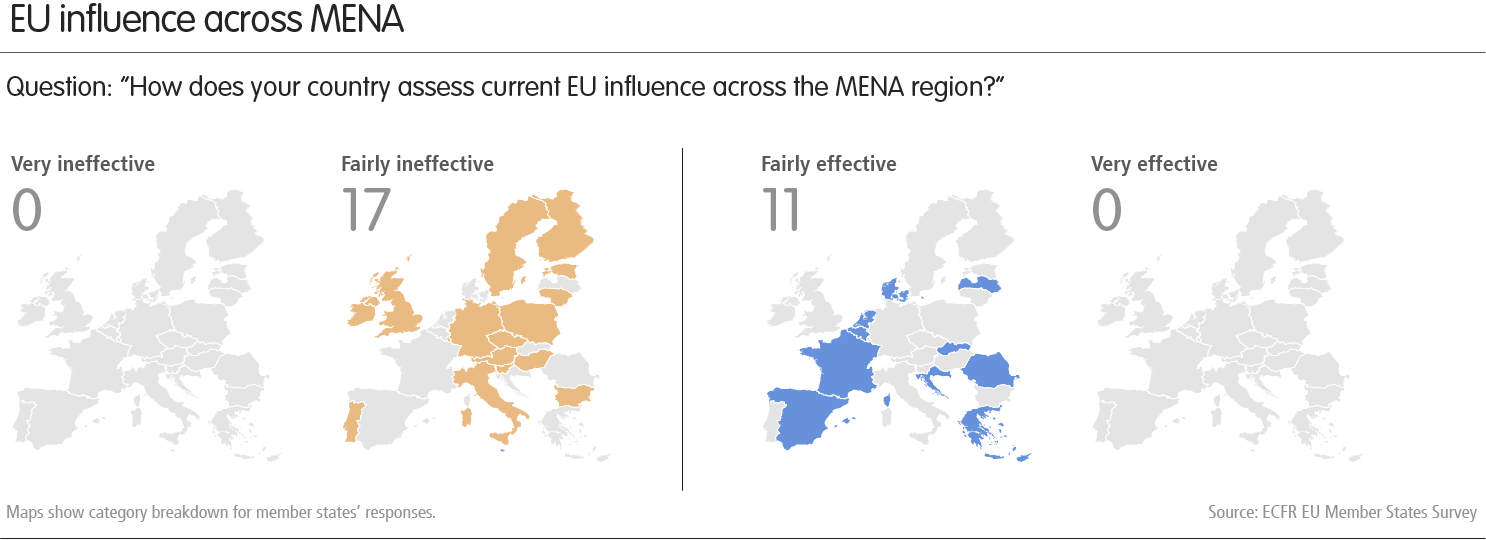

The project shows that, in the region and beyond, there is a worrying degree of disdain for Europe’s position and a sense that its influence is waning. Even some Europeans acknowledge this – with one high-profile official telling ECFR that Europe’s position across MENA has “never been so divided and weak” (ECFR interview, 2019). Indeed, more than 60 percent of respondents to ECFR’s survey described the EU’s regional role as “fairly ineffective”.

But the project also demonstrates that the EU has the potential to exert greater influence by focusing its efforts on specific areas. The components of the project highlight the fact that Europeans have leverage, as well as the capacity to act in a more coordinated, strategic manner – and that a stepped-up European role would have an impact on regional actors. Importantly, the project reveals that there is an appetite among a coalition of member states – if not the full 28 – to work together with greater unity to protect their critical interests across the region.

Of course, overcoming internal and external challenges is never easy; it requires considerable time, effort, and political capital. But Europeans facing a tumultuous neighbourhood – one in which the forces of competitive multilateralism grow ever fiercer – need to consider how they can act to greater autonomous effect.

Key findings

1) Overcome EU disunity

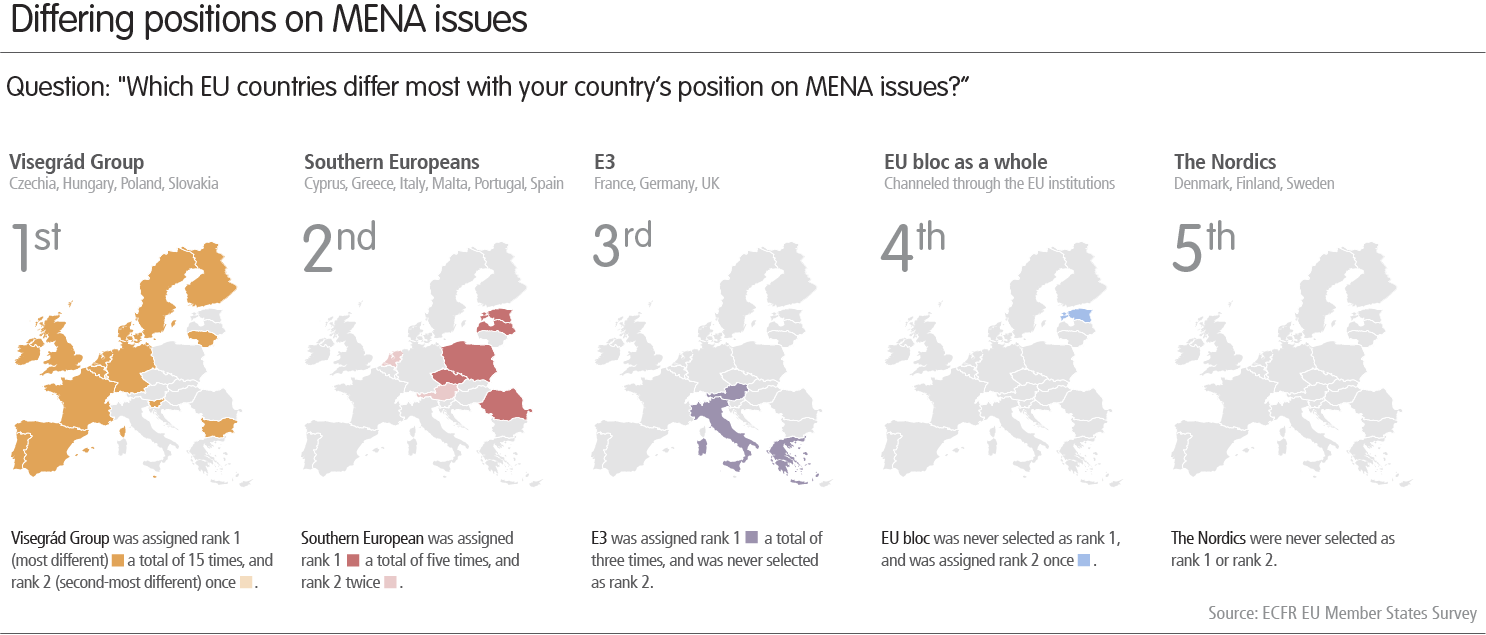

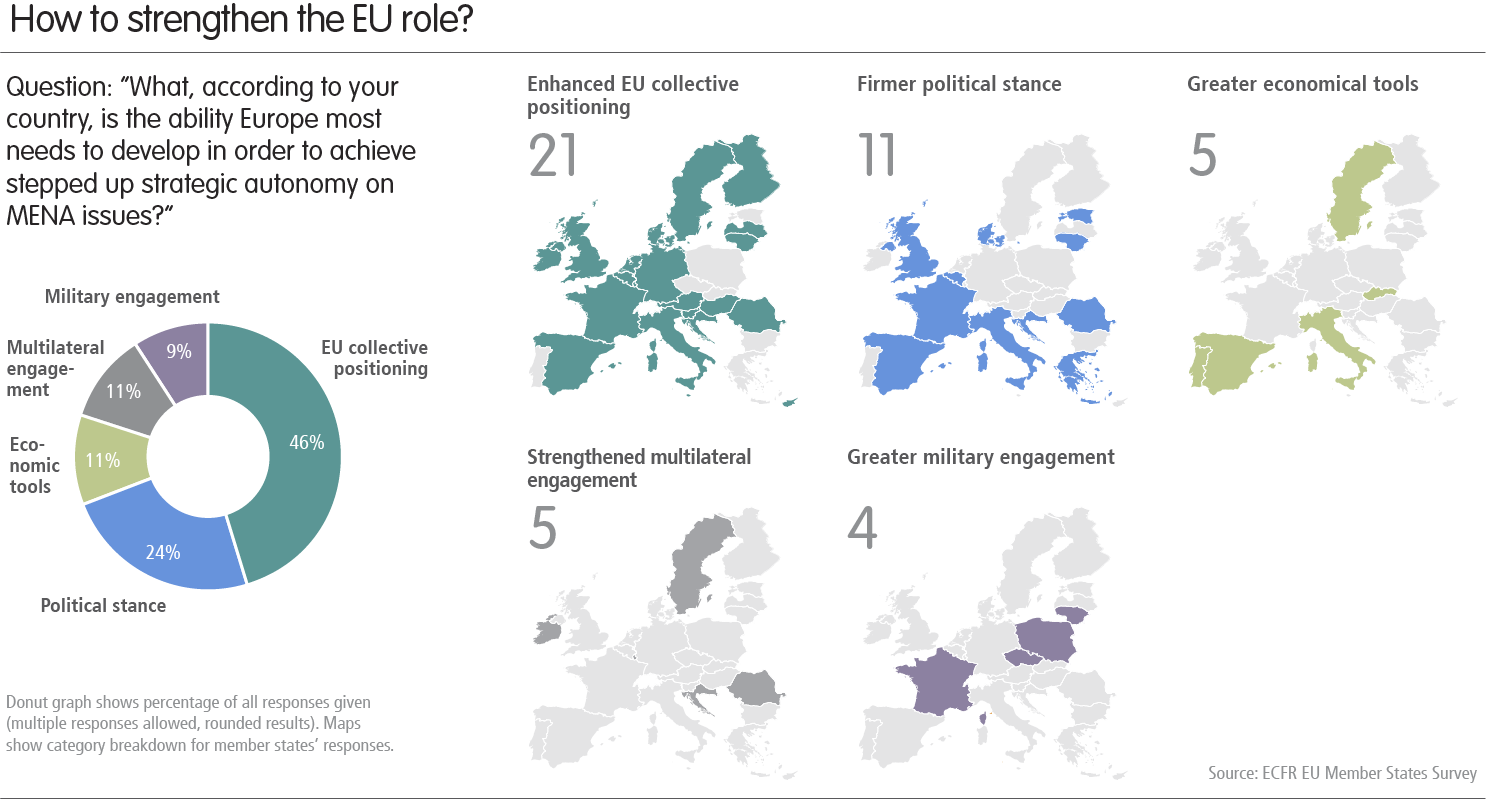

In explaining the reality of European weakness, the project identifies two core issues. Firstly, there is a profound lack of unity in Europe’s response to challenges in the MENA region, which constantly undermines its efficacy. On nearly all regional issues, a lack of European consensus has repeatedly blocked decisive action – as respondents in 20 of 28 member states recognised.

Respondents in 13 member states identified the intransigence of the Visegrád group as the biggest impediment to a common European position. But there are numerous other fault lines, such as the Franco-Italian split on the Libyan war – which prevents Europe from effectively responding to a crisis that has direct implications for its core interests.

Many of the regional essays emphasise a lack of European unity as a key factor in the EU’s weakness. As Nimrod Goren points out, “Israelis tend to view the EU as being less important than it once was. This is partly due to its internal divisions and increasingly inward-looking nature.” This viewpoint is mirrored in Faisal Abu al-Hassan’s assessment: “most Saudi leaders do not take the EU seriously as a geopolitical actor, due to its frequent inability to agree on common foreign or defence policies.”

The essayists also argue that internal weakness has left the EU vulnerable to manipulation by other powers, which are able to pick off member states. “Keenly aware of intra-European divisions on Middle East policy, the Israeli government has increased its attempts to exploit these differences in recent years,” writes Goren. The sentiment is, as Yury Barmin argues, also apparent in the Kremlin: “Moscow sees this discord on a variety of issues – ranging from the EU’s failure to find consensus on hosting refugees to the open rivalry between France and Italy over Libya – as, to some extent, an opportunity to enhance Russian influence.”

2) Decouple from US policy

The second key weakness reflects what Europeans bring – or, rather, do not bring – to the table. The EU is widely seen as a negligible political player in the MENA region, as it continuously looks to US leadership in a manner that precludes an independent policy on regional developments. This is often accompanied by European countries’ unwillingness or inability to deploy their militaries in the region, at a time in which hard power is increasingly important there.

The EU is widely seen as subservient to the US even in its traditional areas of strength – namely, economic and trade policy. The project’s Iran contributor, Hassan Ahmadian, notes that European governments failed to “push back against draconian US sanctions and thereby pursue their stated goals”. As a result, “most Iranians see Europe as a weakened global player that can neither incentivise nor penalise Iran in a meaningful way”.

Of course, this EU disunity and weakness comes at a time when Europeans are aware of their increasing divergence with the Americans – a trend most clearly on display in disagreements over the fate of the Iran nuclear deal, but also visible on issues such as the Middle East Peace Process. President Donald Trump’s recent decision to reduce the US military presence in north-eastern Syria provided yet another demonstration to Europeans that their close ally is not inclined to consider their interests or consult with them on questions that affect European security.

However, in all these areas, European capitals have shied away from direct confrontation with Washington. Not least due to its security umbrella, the US continues to exert a strong influence on EU member states. For instance, respondents from Romania, Hungary, and the Czech Republic emphasised that their country would be willing to disrupt EU unity to remain aligned with the US on the Israel-Palestine conflict. Similarly, Poland and Estonia would support the US position on security matters even if doing so weakened the collective EU position.

On the few occasions that it has sought to articulate an independent foreign policy, the EU has proved ill-prepared to deal with US pressure. Washington has targeted secondary sanctions against European countries’ interests over their support for the Iran nuclear deal, highlighting European unwillingness to deploy the necessary political capital to effectively challenge the current US administration.

This assessment of Europe’s self-imposed limitations and irrelevance is shared by US officials – who, as Jeremy Shapiro writes, broadly “feel that Europeans talk a lot about the Middle East but do very little”. The US government, he argues, “remains dismissive of European influence largely because it believes Europeans cannot really formulate an independent policy on the Middle East … Europe’s dependence on the US for its own security places a firm limit on the degree of opposition it will muster to American policies.”

3) Make better use of European assets

ECFR’s survey indicates that, rather than having a weak hand, the EU plays a strong hand very weakly. The bloc has important sources of economic and political influence – but it squanders them. The survey highlighted the importance of several European assets in particular.

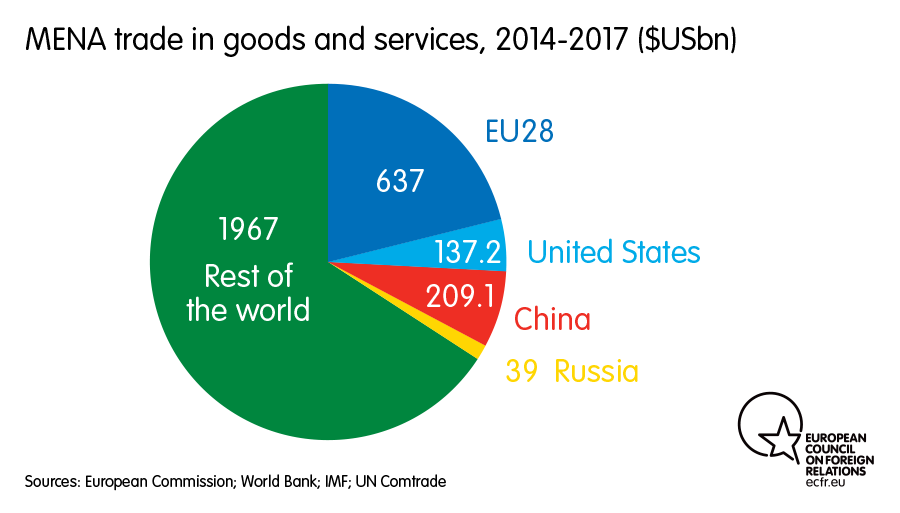

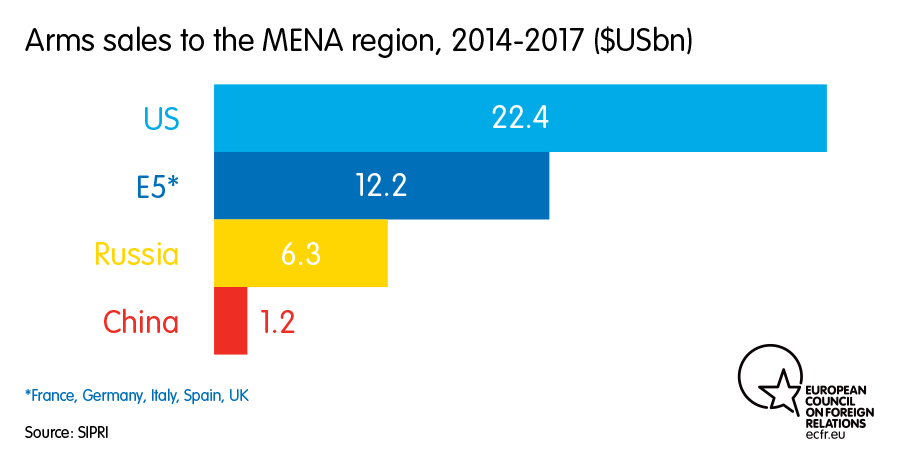

The first and most obvious one is economic. Taken as a whole, the EU is the MENA region’s most important trading partner: the value of trade between the two averaged $637 billion per year between 2014 and 2017. This represents around 21 per cent of the MENA region’s global trade – far more than that with other international partners, such as China ($209 billion) and the US ($137 billion). France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom collectively sold weapons worth $12 billion to Middle Eastern countries between 2014 and 2017, ranking behind the US ($22 billion), but ahead of Russia ($6 billion) and China ($1 billion).

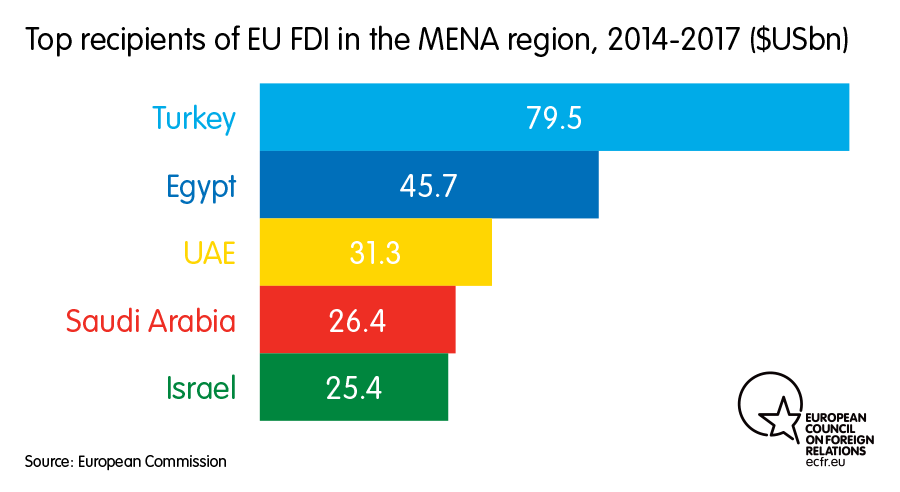

Collectively, the European Commission and the E5 contributed an average of $8.2 billion in development assistance and humanitarian aid per year to the region in this period – an amount second only to that from the US, at $10.9 billion. The European Investment Bank made loans of more than $2 billion per year between 2014 and 2017. Alongside this, EU foreign direct investment into the MENA region averaged around $292 billion per year in the same period, with significant amounts flowing to Egypt ($46 billion) and the UAE ($31 billion).

In theory, these economic links could provide the EU with a significant degree of leverage. But, in practice, this is difficult to achieve, given that these ties also benefit European economies. Moreover, European trade and aid are often devoid of any accompanying strategy that would transform them into political capital. At its core, European leverage is not a question of pure economics. As the essays in this project make clear, Europe will remain rudderless in the MENA region unless it combines its economic advantages with a stronger political position – a reality that member states begrudgingly acknowledge. On Iran, the EU and its member states have demonstrated an inability to inject the necessary political support into an economic package aimed at preserving the JCPOA. But they can make a difference. The EU’s practice of differentiating between Israel and Israeli settlements within its bilateral trade relations illustrates how the bloc’s trade regulations can provide it with a degree of normative power. On Syria, meanwhile, Europeans may be able to play economic cards to try and shape a better outcome – but only if they do so in a coherent fashion tied to a goal that is realistic rather than illusory.

Europe’s second asset is diplomatic. It is widely seen as having significant diplomatic influence – in principle, if not in practice. This stems from the positions of France and the UK as permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, as well as the collective weight of the EU bloc. Policymakers across the MENA region consistently highlight the clout that a combined and independent European political position could have. Here, the EU also under-uses the influence that it could gain through its many partnership agreements with MENA countries. Turkey has by far the most privileged relationship with the bloc, due to its membership of the EU’s Customs Union. On a second tier, the EU has important Association Agreements with countries such as Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Morocco.

This political influence is tied to Europe’s capacity to confer a degree of legitimacy on MENA states, some of which value European governments’ endorsements as a source of international credibility. The leverage that Europe gains through this dynamic may be limited, but one should not discount it entirely. One (negative) example of this is France’s and the UK’s de facto endorsement of the war in Yemen, which legitimised the ongoing military campaign waged by the Saudi-led coalition. In the future, the EU’s reaction will be important in determining whether the US plan for the Middle East Peace Process (should it ever be released) lives or dies.

As Anas el-Gomati points out, these arrangements potentially give the EU “diplomatic gravity”. But the bloc may not have this edge over other powers for much longer. Russia has been busy significantly expanding its political ties across the region. China too is making political inroads into the region, signing Comprehensive Strategic Partnerships with Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

The EU’s third asset is its perceived neutrality at a time of regional polarisation, in which the US appears to be increasingly partisan and erratic in its policymaking. As several essayists argue, there is less sensitivity about European engagement in the region than that of other actors. This could give the EU the credibility to advance mediation processes and promote security mechanisms in line with its core interests, given the manner in which ongoing conflict has fed migration and terrorism challenges. Even among Iranian policymakers – who have taken an increasingly dim view of European power in recent years – there is still hope that French President Emmanuel Macron can de-escalate the confrontation between Washington and Tehran over the Iran nuclear deal.

Moreover, civil society and governments in the MENA region continue to see the EU as a key potential partner in domestic governance and economic reform programmes. Europeans have long recognised that the region needs more efficient and representative governance systems if it is to address public discontent and provide stability. Europe has a strong interest in stepping up its engagement to support such reform efforts and thereby address key structural deficiencies. For example, Renad Mansour suggests the EU has untapped potential in providing reconstruction assistance and building accountable institutions in Iraq – measures that are essential to restoring stability there. Similarly, European states could do considerably more to support the democratic transition in Tunisia. In both cases, European support has been underwhelming to date.

4) Pick the right priorities

If it is to enhance its leverage across the MENA region, the EU and its member states will require more than just the right assets. The bloc must also pursue a smarter set of policies – ones that can bridge the gap between its pressing domestic priorities and the realities of a region that is increasingly shaped by realpolitik. The challenge for Europe, then, is to use the assets it has in service of a unified and coherent political programme.

The widespread sense that Europe does not do so is especially apparent in north African countries, many of whose economies are deeply reliant on European aid and investment. Instead of strengthening mutually beneficial strategic partnerships in north Africa, European countries are increasingly fixated on their short-term interests there – due to domestic concerns. “There is a sense among Tunisia’s officials and elite that Europeans view the country through only two lenses: migration and counter-terrorism,” argues Youssef Cherif.

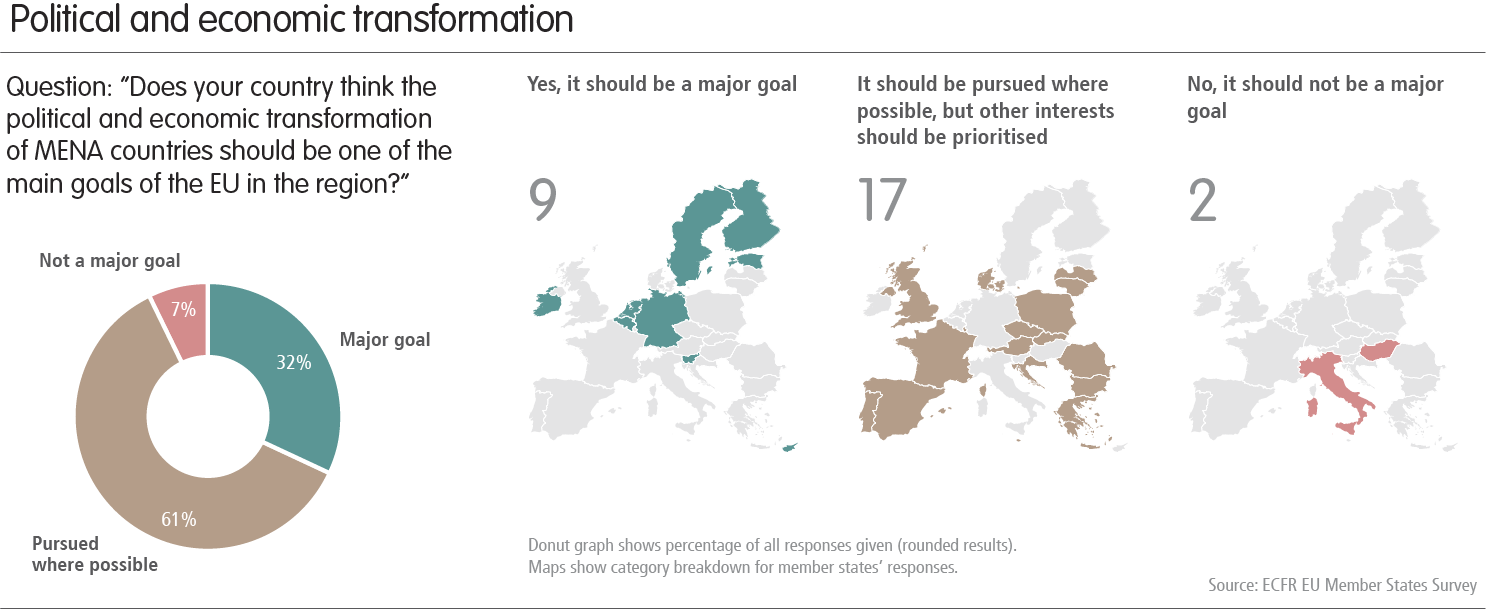

Here, the EU should focus on developing programmes of engagement that are better tailored to its capabilities and long-term interests. Europeans need to balance their current focus on migration and counter-terrorism with steps towards lasting regional stability, using the economic and political assets at their disposal. ECFR’s survey of member states shows that there is little appetite in Europe for an ambitious agenda – with less than one-third of member states regarding political and economic transformation in north Africa as a priority. Nevertheless, it remains in Europeans’ long-term interests to reinforce sustainable governance systems, which are an integral part of efforts to tackle the drivers of regional protests and instability. And the EU’s policy tools are well suited to supporting and encouraging reform projects that can gain traction in the region.

As part of this, Europeans need to be more focused and strategic in their deployment of economic influence. They have devoted insufficient attention to countries in which such influence can have a relatively large political and economic impact, such as Iraq, Lebanon, and Tunisia. This contrasts with, for example, China’s practice of directing its investments towards infrastructure that is of strategic importance to its Belt and Road Initiative.

The EU should also position itself as a mediator that will invest in de-escalation efforts, particularly in the conflict between Iran and an alliance that includes Israel and Saudi Arabia. With MENA countries increasingly distrustful of the US, there may be an opportunity for European actors to carve out a more independent and influential role for themselves. In this respect, Faisal Abu al-Hassan sees French and UK membership of the UN Security Council – as well as a Saudi Arabia’s tendency to turn towards European partnerships when it is frustrated with the US – as important. Indeed, several Middle Eastern states now look to Europe for greater support in conflict mediation. Qatar sees Europeans as “potential partners in a multilateral regional order that denies its opponents the ability to shape events through coercion”, argues Nayef bin Nahar. Similarly, Mansour believes that EU engagement can make a positive contribution to “mediation of the US-Iran dispute”. Active European mediation efforts are not an end in and of themselves. They represent a means of moving the region towards a much-needed stabilising path, in line with European interests – and doing so in a fashion that increases Europeans’ ability to project influence by shaping regional developments.

Here, individual EU member states should play to their strengths. The UK could use its partnership with Saudi Arabia to press for greater Saudi outreach to Iran, as well as further movement towards a sustainable ceasefire and an inclusive political process in Yemen. France could take a similar approach to the UAE, given Macron’s close relationship with Emirati leaders. This should be accompanied by a push – again, one likely led by France, but supported by other member states – to persuade Iran to commit to meaningful de-escalatory measures. These efforts could be supported by other member states in some cases. For example, Sweden has shown a willingness, and a valuable ability, to play a coordinating role in the UN-led Yemen process – as has Germany in north Africa, with its attempts to facilitate a new political process in Libya. For its part, the EU could try to coordinate the regional security proposals now in circulation – including those from Iran and Russia – with the aim of drawing them into a shared diplomatic and security effort that avoids duplication and competition.

European military power, although often deprecated, can also be an important source of leverage, if used wisely. While avoiding the sort of military intervention that lies at the heart of many of the MENA region’s problems, the EU and its member states should be willing to play a greater security role. European countries’ recent failure to cooperate to protect their maritime interests in the Gulf of Hormuz was a stark reminder that they need to act with greater coherence on security matters if they are to enhance their influence. Similarly, it is hard for Europeans to criticise the US withdrawal from north-eastern Syria when they refused to deploy necessary military support to the mission. Members of the EU may have little desire to increase their military capabilities in the region, but they can do more by working through a series of existing European military missions. This includes the British and French military deployments in the Gulf, as well as several advisory operations that fall under the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy, which could serve as umbrellas for joint operations in defence of common interests such as safe passage through key waterways.

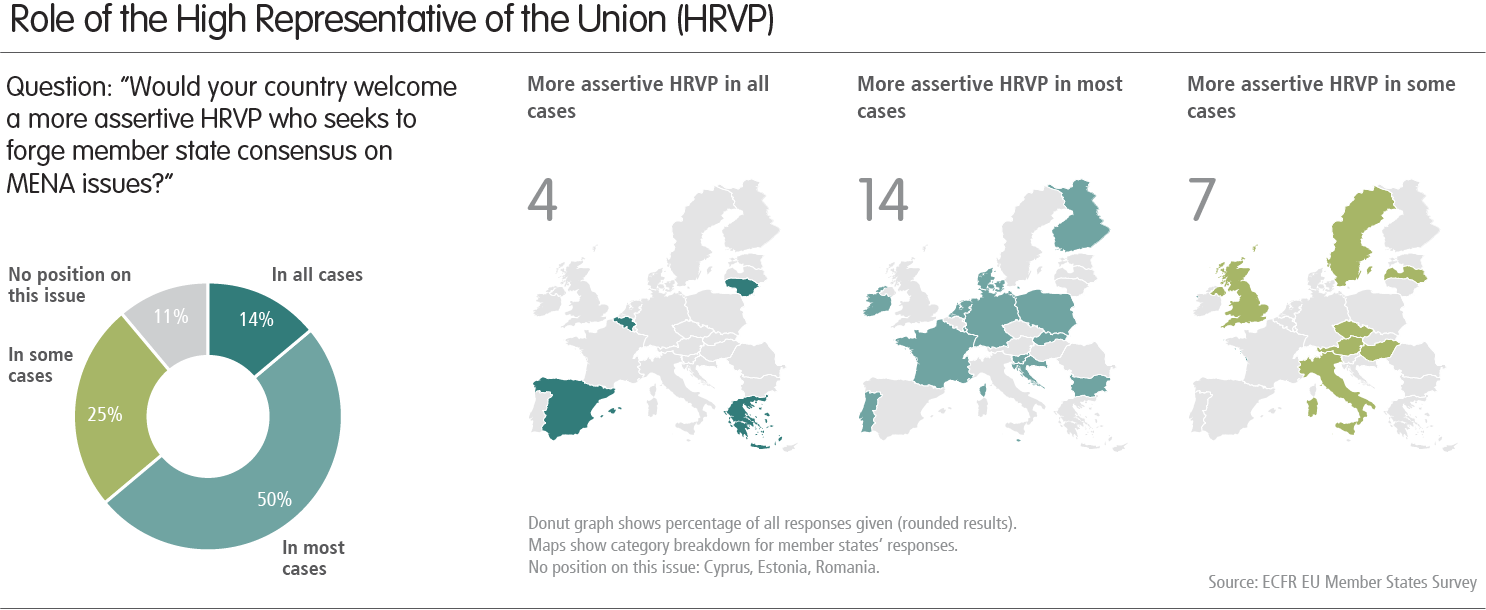

5) Build European coalitions

There are reasons to hope that Europe can better manage its internal divisions in the future. More than half of European respondents to ECFR’s survey backed greater assertiveness from the EU high representative for foreign and security policy in relation to the MENA region. This reflects a sense that, in the past, they have devoted too little time to forging internal European agreement on key issues. In this regard, the European External Action Service (EEAS) must do more to forge a consensus between member states rather than merely seeking to reflect one. In doing so, the EEAS must feel more confident in implementing existing political mandates granted to it by the European Council.

But to overcome the challenge of EU disunity and some member states’ efforts to minimise the impact of every common initiative, Europe’s engagement with the MENA region should also move towards a greater focus on smaller, more agile, European coalitions, as spearheaded by the efforts of the EEAS and the E3 (France, Germany, and the UK) on the Iran nuclear deal. This practice has taken on new life in the past year through EU statements at the UN on behalf of 27 member states, in the face of Hungarian vetoes on the Middle East Peace Process. At a time when the Brussels foreign policy machinery has become increasingly clogged by member state dissension, Europe’s continued relevance as a political actor in the Middle East and north Africa will increasingly depend on the ability of core groups of member states to drive forward and operationalise EU policy.

Smaller, more flexible, coalitions should now become prominent vehicles for policy. Given that nearly all member states see France as the pivotal European actor on MENA issues, it is incumbent on Paris to show a greater willingness to work within coalitions – and to change its preference for unilateral action in Middle Eastern affairs – if Europeans are to forge more coherent policy positions. But there is also increased space for Germany to assume a greater leadership role, particularly in view of Brexit. Elsewhere, smaller states should look to carve out more assertive coalitions in partnerships with the EEAS on relevant issues. This approach would build on the past successes of small European coalitions, particularly those on the Iran nuclear deal.

Europeans today face a daunting set of challenges across the Middle East and north Africa. And things are only likely to worsen, given Europe’s deep structural deficiencies. Against the backdrop of a rapidly shifting global environment – one in which the US-led liberal order is in decline due to advancing hard-power and geopolitical realities – it is imperative that Europeans learn to act for themselves.

While this may be a difficult outcome to imagine given the long-standing sense of European marginalisation, it is not impossible to achieve. If Europeans are willing to change course and start using their levers of influence – perhaps not military ones, but certainly their political and economic assets – in a coherent fashion and in support of core interests rather than short-term goals, they may well see regional players begin to take them more seriously. As argued by the EU’s incoming foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, the bloc has “the instruments to play power politics. Our challenge is to put them together at the service of one strategy”. This will require a new impetus in which key actors focus on working together to create much-needed European coalitions or core groups on regional issues. It is a necessary moment for a shift in this direction.