Promoting European strategic sovereignty in the eastern neighbourhood

Summary

- Since 2002, the European Union’s goal in its eastern neighbourhood has been to ensure that it is surrounded by democracies that uphold the rule of law while maintaining market economies and open societies.

- This goal remains relevant and important: as recent events in Belarus show, authoritarian stability in the neighbourhood has always proved to be an illusion.

- Russia has used political, economic, and military means to contest the EU’s support for the transition to democracy and market economies in eastern Europe.

- The EU’s tendency to shy away from security issues has helped make covert operations and military threats Russia’s tools of choice in the region.

- To counter these efforts, the EU’s neighbourhood policy should focus on the rule of law and judicial reforms, media regulation and information warfare, security sector reform and capacity building, and cyber and energy security.

- The EU should also add a military and security dimension to its assistance in reforming Eastern Partnership countries’ defence sectors and armed forces.

Introduction

In recent years, several trends have forced the European Union to take a harder look at its foreign policy. One such trend is the EU’s growing realisation that it needs a greater capacity to act independently on some external matters, and to do so in a strategically sovereign manner. Another trend is the EU’s increasing awareness that the world has become more “geopolitical” – that, because other powers are behaving with greater assertiveness, it will lose its voice in a disordered world unless it becomes the influential actor it wants to be. Accordingly, the effort to build a more geopolitical Europe has become an explicit objective of President Ursula von der Leyen’s European Commission. And it is a goal shared by most member states, whose influence will wane unless the EU acts with more ambition, force, and cohesion.

The covid-19 crisis may dominate the EU’s current priorities, but it has not caused other powers to relent in their assertive pursuit of geopolitical goals. The pandemic has highlighted many of the structural, administrative, and security weaknesses that have long haunted countries in eastern Europe. In the meantime, alleged vote-rigging in Georgia’s recent parliamentary election has caused a national crisis. And Ukraine has experienced a rollback of democratic reforms and a constitutional crisis stemming from a controversial court ruling. A rigged presidential election in Belarus has led to widespread protests and the contestation of President Aliaksandr Lukashenka’s rule by various camps in civil society. A brutal crackdown by the regime and a clandestine Russian intervention have kept Lukashenka in power – at least for now. Due to these events, Russia slightly altered its Kavkaz 2020 exercises – originally intended to be a signal to Ukraine – as it needed mobile forces to act as a deterrent against both Belarusian protesters and the West. In a crisis with a more overt military dimension, the dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh escalated into a full-scale war.

The EU has limited influence on such developments, despite the fact that it is the most important trading partner of all countries in the Eastern Partnership; invests billions in economic, societal, and infrastructure programmes there; and remains a kind of role model (and desired study, work, and tourist destination) for citizens of these states. The EU’s problems in the region go beyond the difficulty of converting soft power into hard power. All Eastern Partnership states face urgent security challenges that complicate policymaking. As the EU provides only marginal help in this regard, they often see European interests as being of secondary importance. For this reason, Donald Tusk, head of the European People’s Party, argues that “we need to increase cooperation between the EU, its Member States and select members in matters of security, intelligence, and defence. A new initiative – a security compact of the Eastern Partnership – is a good starting point for such a discussion.” And, while the Eastern Partnership has achieved much, the EU has few opportunities to gain political influence in the region – or to build these countries’ resilience against foreign interference.

This paper discusses how the EU can strengthen its strategic sovereignty in its eastern neighbourhood. And it discusses why the EU has not yet come to terms with what it would take to defend its interests in the region. (The paper does not primarily focus on how Europe should deal with Russia, which separate assessments cover in relation to deterrence and defence, and protection against hybrid threats.)

The EU’s interests and goals in Eastern Partnership countries

The EU’s basic interest in its eastern neighbourhood is to be surrounded by a “ring of friends”, as then European Commission president Romano Prodi put it in 2002. The following year, when launching its neighbourhood policy, the EU announced that conflict resolution was one of its key priorities. Since then, there has been a significant increase in conflict in the bloc’s neighbourhood – but no parallel rise in member states’ level of ambition to address this sensitive area. For the EU, post-Soviet countries’ transition from communism to competitive democracy, administrations bound by the rule of law, and functioning market economies would not only enhance peace and stability but also promote economic growth, sustainable development, cross-societal and cultural ties, and sustainably strong relations in its neighbourhood. Despite globalisation and the growing power of long-range communications, countries’ immediate neighbours are still more important than distant powers in trade, investment, migration, and security.

While the EU’s support for this transformation has produced mixed results, the bloc needs to acknowledge that a total failure of the process in its eastern neighbourhood is possible and would have dire consequences. Belarus may serve as a cautionary tale of what can happen when a political and economic transformation fails. Now that Lukashenka is nearing old age and experiencing a rapid decline in his legitimacy due to his suppression of opposition protests, there are questions surrounding issues of succession, Belarusian sovereignty in the Union State, and the durability of the country’s economic model. At best, Belarus will remain a weak and poor country on the EU’s border. At worst, it will become a co-belligerent client state that Russia uses to directly threaten and challenge EU sovereignty and territorial integrity. Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia could become a Moscow-dominated zone of instability – from which the Kremlin could stage clandestine subversion and conventional military operations. With no territorial insulation comparable to that provided by the Mediterranean, this would be a more powerful threat to the EU’s eastern member states than even the unrest the bloc faces to the south.

Such turmoil belies arguments in favour of “authoritarian stability”. Even in breakaway regions tightly controlled by the Russian intelligence services, the local authorities are often challenged and sometimes displaced by public revolts. In South Ossetia, protests against a disputed election in 2012 ended with the death of the opposition candidate (who may have won that vote). In Abkhazia, the nominal “president” has been deposed twice – in 2014 and 2020 respectively – by popular revolts sparked by an allegedly rigged election. Even if the EU were to end its support for political and economic transformation in its eastern neighbourhood, popular desire for an accountable government would not go away – and nor would the instability created by failed political processes.

The EU’s main goal in the Eastern Partnership is to forge the “common area of shared democracy, prosperity and stability” recently referred to by the European Council. And the bloc has other declared areas of interest there. For some European leaders, political transformation is still a prerequisite of efforts to achieve other goals. Efforts to fight corruption, organised crime, and money laundering within both the EU and the eastern neighbourhood have gained some media attention in the wake of the Mueller Report and the scandal surrounding President Donald Trump’s decision in 2019 to fire the US ambassador to Ukraine. Ultimately, the integrity and professionalism of local investigative and judiciary authorities will be a key factor in whether the EU can achieve its objectives in its eastern neighbourhood.

Joint EU-Eastern Partnership declarations also cover issues such as workforce mobility and migration; infrastructure; young people; education; ethnic minority groups; digitalisation; steps towards economic alignment; the European Green Deal; healthcare, particularly in relation to covid-19; and gender equality. However, these are fairly apolitical, bureaucratic portfolios that say little about Europe’s ability to implement its foreign policy. And they are not areas that third parties have weaponised against EU or Eastern Partnership states. This is partly due to the fact that Belarus and Azerbaijan generally follow different political norms to the EU but are formally part of its eastern neighbourhood. Consequently, there is some diplomatic pressure for the EU to engage with them – or to talk through practical issues that arise as general concerns within the Eastern Partnership.

In terms of the EU’s efforts to gain political leverage over decisions in the Eastern Partnership, energy links with Russia are the only other strategically important issue covered by agreements between the sides. Nonetheless, energy transit is an area that Moscow uses to apply pressure on Eastern Partnership states (and that the EU uses to ease such pressure). Hence, energy issues may make for spectacular headlines in themselves but they are inseparable from the broader struggle over the rules that apply to, and the rights of, Eastern Partnership states. Put another way, disputes over energy concern the issue of whether the EU can and should support Eastern Partnership states in their transition to liberal democracy, an open society, the rule of law, and free markets – or whether they should maintain close ties to Moscow.

The EU’s support for political and economic transitions in the Eastern Partnership has never been uncontested. Russia views the instability, vulnerability, weakness, and dependency of these countries as a key mechanism through which to exercise influence in its immediate neighbourhood. Russia has used economic dependencies – particularly those on oil and natural gas – to gain leverage over Georgia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Moscow has also used targeted corruption, information warfare, election fraud, and intelligence operations to discredit, extort, or intimidate political actors, with the aim of securing power for individuals it believes will protect Russian interests. As if that were not enough in itself, Moscow has also made use of military force – overt or otherwise. Needless to say, the reforms related to the rule of law, free markets, and the political system that the EU envisions for its neighbourhood would decrease Eastern Partnership countries’ vulnerability to Russian pressure.

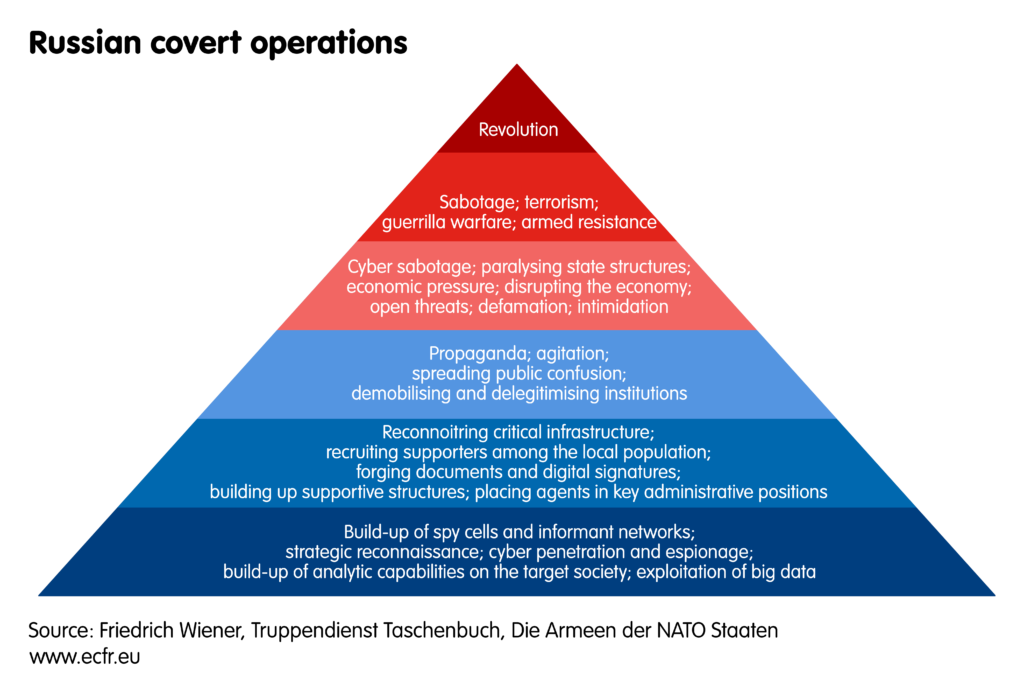

Russia’s tactics, combined with its lack of constructive initiatives in the region, have earned it a reputation as a “strategic spoiler”. This label is particularly apt in relation to covert operations, which build clandestine networks within a country to weaken its institutional, political, economic, and security structures. The ultimate aim of such operations is to make the country succumb to foreign pressure or, if it does not do so, ignite a ‘domestic’ conflict that provides a pretext for intervention. For Moscow, covert operations are nothing new – as shown in the graphic below (an updated version of one depicting 1970s Soviet covert operations against the West and its allies in the developing world).

Ukraine provides many examples of how Russia applies these tactics (as described elsewhere). Events under then-president Viktor Yanukovych showed that the Kremlin has ample opportunity to make use of local strongmen, oligarchs, and public figures willing to help it achieve its aims. Power centralisation, state capture, systemic corruption, and attacks on the independence of the press and the judiciary are attractive to local elites and strongmen who seek to monopolise power. While there is a blurred boundary between domestic weakness and foreign-induced vulnerability, much of the success of covert operations rests on the exploitation of pre-existing divisions within a country. In practical terms, this boundary does not matter to the EU’s policymaking: the bloc needs to mitigate Eastern Partnership states’ institutional weaknesses regardless of their origin.

The EU has sometimes tried to negotiate transitional arrangements that would turn competition with Russia into a mutually beneficial situation. It has done so by engaging with Russia directly, offering economic and societal concessions, and reform and modernisation assistance – as envisioned in the CFSP Common Strategy. The bloc has also attempted to negotiate peace agreements for protracted territorial conflicts by offering Russia a co-management position in common security institutions, as stipulated in the 2010 Meseberg Memorandum. However, when they have tried to implement such initiatives, Russia and the EU have been unable to create a shared vision for the region. This is due to their deep ideological differences on the European security order. Instead of fostering cooperation, these failed efforts have heightened mutual suspicion.

Risks and vulnerabilities of EU policy

In the two decades that followed the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Russia’s détente with the West did not prevent it from conducting efforts to gain influence in its neighbourhood – including through military means. These destabilising initiatives targeted post-Soviet states that had weak institutions; no tradition of leadership and political responsibility (as the Soviet leadership was concentrated in Moscow); dysfunctional administration; inefficient, compromised, and uncontrolled security services; a polarised political culture dominated by cynicism and the manipulation of information; populations that were detached or even alienated from politics; and media outlets that were dependent on external sources of finance. As such, post-Soviet states’ resilience against covert operations was low to start with. On every level of the pyramid depicted above, the Kremlin had put assets in place to exploit these weaknesses.

Moscow’s covert operations only catch the attention of the West when they reach the top of the pyramid and separatist violence begins to threaten the survival of individual nations. But, by this point, it is often too late to mount a strong defence. The most effective way of fighting covert operations is to focus on their roots (depicted at the bottom of the pyramid) – to prevent the enemy from subverting key structures, penetrating the target’s information space, building up proxy organisations, compromising local IT networks, or recruiting local officials and operatives.

However, states can only build such defences if they have functioning law enforcement and security organisations that carry out their duties in a professional and accountable manner. Of course, sustainable reform in post-Soviet countries is not only about countering Russian subversion; it is also about state- and institution-building in its own right. However, Western support efforts for these countries will fail if they ignore geopolitics. This is because fragile institutions – the judiciary, the police, the prosecutor’s service, intelligence agencies, the military apparatus, financial regulators, national banks, and public media organisations – face a persistent, coordinated, and covert assault on their integrity and functionality.

The strategic problem for the EU is that its broad outreach to civil society groups and long-term economic integration policies in post-Soviet countries are vulnerable to initiatives that hijack the local political process. Such initiatives are not part of normal democratic competition, but are usually driven by vested interests and Russian operators – who primarily aim to reverse reforms related to the rule of law and effective governance, and to re-establish and expand clandestine subversive structures. Election contenders often promise one thing during their campaigns – such as social benefits or new reforms – but deliver quite another once in power, reversing previous reforms and subverting institutions. Hence, they immediately create a gap between their electoral mandate and their policies, leaving the EU unsure whether to respect the local political process or hold governments to their commitments.

In this environment, the EU has implemented what might be considered fair-weather policies: it proposes economic incentives and the prospect of closer integration, but the capacity to fulfil these offers – and implement reforms – depends on the political will of local leaders. The model works when the EU deals with stable, wealthy, and secure states such as Switzerland or Norway. But it does not work with Eastern Partnership countries.

Some of these shortcomings stem from the core design of the Eastern Partnership, the European Neighbourhood Policy, and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs), which primarily concern trade, regulatory compliance, and economic integration. The EU has generally considered issues related to the rule of law and administrative reform to be only supplementary to these arrangements.

But, in fact, it should be the other way around. Only successful rule of law and administrative reforms can allow citizens, entrepreneurs, and investors to fully benefit from regulatory alignment and economic integration. Furthermore, the EU applies too few criteria to Eastern Partnership countries in relation to good governance and the rule of law. Hence, it is difficult for the bloc to create clear conditionalities on these issues. The EU has paid insufficient attention to the implementation of reforms – instead relying on box-ticking exercises. For example, Ukraine’s judicial reform has produced workable constitutional amendments and laws, but vested interests in the judiciary have hijacked the decision-making process on the readmittance of judges. Eventually, the country ended up with old cadre judges, whose use of their positions to sabotage reforms has led to the constitutional crisis in the country.

In Eastern Partnership countries, vested interests frequently circumvent, dilute, or counteract reforms through additional legislation or administrative decrees. The problem is exacerbated by the EU’s lack of a coherent and meaningful policy for supporting civil society organisations and independent media outlets – both of which are essential to democratic accountability and the fight against disinformation. And, finally, the EU has no structured capacity building programme focused on the judiciary, despite the fact that Eastern Partnership countries’ judicial systems are notoriously weak and they have repeatedly failed to reform them on their own. The same is true of administrative reform and capacity building. The EU has no capability to directly provide judicial or administrative services to an Eastern Partnership country – in, for example, presiding over a politically charged or sensitive trial.

There are other shortcomings in EU policy created by the marginalisation of security issues (in both the union’s internal politics and its foreign policy). They include:

- A lack of cyber security, cyber resilience, and cyber capacity building initiatives under the European Neighbourhood Policy.

- A lack of a coordinated approach to financial security issues in Eastern Partnership countries, particularly in relation to money laundering, other financial crimes, and foreign political and media funding.

- A lack of EU intelligence assets on the ground that can assess situations and, especially, personnel without relying on only open-source information or local intermediaries. In an operational environment characterised by weak institutions, poor administrative integrity, and weak judicial oversight, much depends on personnel rather than formal offices, laws, procedures, and processes. The EU’s inability to vet people designated for key positions ensures that it is always playing catch-up when reforms begin to break down.

- A lack of capacity building and cooperation initiatives designed to help local intelligence and police services detect and foil Russia’s subversive efforts. (Ukraine is the only country in the neighbourhood with significant intelligence capabilities of its own – and, unfortunately, the effectiveness of even these services is often undermined by domestic politics.)

- A lack of substantive police reform programmes. Corruption within the police remains a major issue in Eastern Partnership countries, undermining the legitimacy and public acceptance of investigative work.

- A lack of a policy that would help Eastern Partnership states safeguard their external borders with third countries, manage asylum and migration issues, and effectively fight cross-border smuggling. (Currently, EU policy in these areas only concerns travel between Eastern Partnership countries and the Schengen area.)

- A lack of support for defence reform in everything from military training and foreign aid to the willingness to deploy armed forces to end a conflict. This shortcoming has helped make military force Russia’s weapon of choice in its efforts to counter EU policy. Russia’s armed forces are relatively powerful (much more so than its economy) and it knows that the EU rarely dares to respond with military operations of its own. European military capacity building could de-incentivise Russia’s use of force by increasing its costs.

A broader shortcoming in the EU’s approach to dealing with adversaries such as Russia relates to institutional compartmentalisation. The EU and the External Action Service have a mandate to deal with countries that have DCFTAs, and with the implementation of these agreements. Many of the incentives for this process – such as macrofinancial assistance – are the responsibility of individual governments or the International Monetary Fund. European cyber security and intelligence assets are exclusively in the hands of EU member states, while military support measures are the preserve of NATO and individual countries within the alliance. It takes time to coordinate all these actors – meaning that the EU reacts more slowly to unexpected events than other powers do.

The EU’s reform support and security assistance initiatives in Eastern Partnership countries do not inform its decisions on accession to the union. Although some EU countries with otherwise ambitious leaders want to permanently replace the membership perspective with “internationally guaranteed neutrality” – without qualifying what that means for affected states – this would still require the EU to protect their security institutions. A lack of such direct support would fatally undermine attempts to establish independent, sovereign, and non-aligned states in the vicinity of Russia.

This problem is nothing new. During the cold war, the West frequently had to support neutral or non-aligned states in their struggle for independence. After the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, for example, the United States immediately increased foreign military aid to Belgrade, equipping 19 Yugoslav divisions from US stocks and providing material and technical assistance to set up a working air force. Military cooperation between Sweden and the United Kingdom, the US, and other Nordic states was key to stabilising NATO’s northern flank during the cold war. When a newly independent Austria faced Soviet troops on its border in the wake of Moscow’s 1956 intervention in Hungary, Washington unilaterally guaranteed the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the new republic. Without military assistance, intelligence cooperation, and sometimes direct security guarantees, it would not have been possible for these states to remain independent and non-aligned during this period. The same rules apply today.

The EU’s capacity as a security enabler on its eastern flank will also determine whether its member states and their top representatives are seen as relevant in Moscow. This will be particularly important for countries that, in the long run, want to foster a strategic relationship with Russia. Contrary to conventional wisdom, such a relationship will not come about due to empathy for the Muscovite elite and their interests, nor acquiescence to them. Russia will only take the EU’s interests into account if the bloc stands its ground.

How to expand the EU’s toolkit

To address Russia’s clandestine operations in Eastern Partnership countries, the EU needs a counter-subversion policy that can protect their economic, financial, societal, and political reforms. This calls for not only a more active and coherent stance on existing policy, but also an expansion of the EU’s toolkit in five key areas:

- Media and information warfare.

- Cyber security.

- Intelligence and security services.

- Defence.

- Energy.

In the first area, past European efforts have centred on support for investigative journalists and fact-finding NGOs. This support came on a bilateral basis or through a coalition of like-minded countries, as seen with initiatives such as the Visegrad Fund. Yet, as important as these measures have been, they have fallen short of their envisioned effects. This is because the content they produce (most of which is available online) only reaches a small audience. As conventional television is still one of the most important sources of information for citizens of Eastern Partnership countries, it is important for the EU to address this medium directly. To establish public TV stations that are editorially and financially independent from the government through broadcasting fees is only the first step in this process. There is also a need for broader support in the form of advice, expertise, programme content, and quality control mechanisms.

The expansion of TV content needs to account for societal diversity. One pattern that has been particularly apparent in Georgia and Moldova is that Russian disinformation on TV targets ethnic and linguistic minorities. With no capacity to provide fact-checking services in viewers’ native languages, the state has de facto abandoned these information bubbles. In Western countries, public broadcasting institutions are responsible for providing accurate, accessible information to ethnolinguistic minority groups. For strategic reasons, they should do so in Eastern Partnership countries as well.

While impartial public services of this kind would provide more accurate content than oligarch-owned TV stations or foreign propaganda channels do, they would not make these sources of disinformation go away. However, changes in the regulatory framework could make it much more difficult to spread disinformation using these outlets’ current business models. Firstly, rules on the transparency of media ownership, the acquisition of media outlets, and advertising and finance would make it more difficult for foreign powers or oligarchs to secretly purchase these assets. Secondly, rules on the financial self-sufficiency of media enterprises would prohibit oligarchs from financing news agencies to manipulate the public debate. They would force media enterprises to live on their own revenues, either through subscriptions or third-party advertisements. It is unlikely that Eastern Partnership states will adopt such legislation on their own, as TV propaganda is an important source of ruling parties’ power and legitimacy. Only EU pressure and conditionalities will change this.

Western European policymakers often assume that the fight against propaganda requires counter-propaganda or censorship. But that is far from the truth. The effort to counter disinformation primarily requires precise intelligence on adversaries’ messaging, content, narratives, emotions, amplifiers, channels of communication, techniques, and tools to increase outreach – allowing for the formulation of a communications strategy that responds to challenges in an appropriate way.

In Ukraine, several EU member states support a variety of local NGOs that have developed considerable expertise in identifying and tracking Russian and local disinformation. However, the EU lacks the structures to absorb information generated by its local partners, adapt its communications strategy accordingly, and, even more importantly, help local actors improve their strategic communications to protect the political process from interference. Although there are capable local actors in Ukraine that the EU can work with on information security, there are few such actors in other countries in the bloc’s eastern neighbourhood (as is particularly apparent in Georgia and Moldova). The EU needs to launch capacity building programmes in this sector.

In parallel, cyber operations are an essential part of covert warfare in the twenty-first century. This can be seen in destabilising efforts involving everything from the use of big data in assessing citizens’ mood and prejudices (and thereby exploiting them through information operations) to espionage, to sabotage missions that paralyse branches of the government or strategic infrastructure. Improvements to cyber security and cyber resilience in the EU and its eastern neighbourhood are necessary to counter subversive actions.

The EU has slowly made progress in this area by making its 2015 Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems and its 2019 Cybersecurity Act part of the legal framework that signatories to a DCFTA must adopt. However, the EU does not provide any technical assistance or capacity building to help countries implement these directives. The main challenges for Eastern Partnership countries in the cyber sector are in: safe storage, processing, and access to data; the security and integrity of electronic communication networks and services; the capacity to prevent attacks, as well as to create effective cyber emergency response teams (CERTs); cyber defence capabilities; cyber hygiene on the user level (both public and private); and networking between domestic cyber structures and those of international actors.

To improve their national cyber capacity, Eastern Partnership states need to forge partnerships with local IT firms. But, in this, there are few such companies that Eastern Partnership governments can turn to – except in Ukraine, which has a significant and rapidly growing IT sector. (Moldova adopted legislation to facilitate growth in the sector in 2019, but it remains to be seen whether this is sustainable under the country’s new government.) Hence, Eastern Partnership countries are dependent on IT companies and services from the US, Europe, Russia, and China. And the use of Russian and Chinese firms raises particularly acute concerns about security.

Many of the steps the EU needs to take first concern domestic cyber security and cyber sovereignty. The bloc should create the legal framework and administrative structures to certify software and hardware; institutions to rapidly coordinate national CERT teams through an EU-wide “super CERT” (currently under development as a Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) project); and cyber forensic and investigative bodies across Europe. These structures could audit Eastern Partnership countries’ cyber security authorities and legislation; develop clear benchmarks and goals for organisational reforms; engage in capacity building programmes; provide critical information on emerging and imminent cyber threats; and liaise with certified local authorities. They could also help adapt EU standards to the rollout of 5G infrastructure in these countries. It is beyond the capacity of Eastern Partnership states to carry out a full technical evaluation of complex supply chains – networks for not only 5G but also, inter alia, government, military, and intelligence communications. Accordingly, they need help from external stakeholders such as common EU cyber security research institutions (which are the subject of another PESCO project).

Functional cyber security structures also have an important role to play in fighting money laundering. Links between national banks and cyber intelligence units have proven important to uncovering financial crimes. Foreign influence operations often depend on the same opaque and illegal financial channels to provide money for operational costs: paying sources; corrupting individuals; funding front organisations (such as NGOs and media outlets); and purchasing storage facilities, weapons, and other assets to prepare armed insurgencies. The kinds of covert operations depicted in the pyramid above are costly affairs. Disrupting their financial support networks would be an effective way to combat them.

This is not only a foreign policy issue, as the EU is working to redefine its rules and regulations to prevent member states from being safe havens for money laundering and other illegal financial operations. Once there is a coherent European legal and institutional framework in this area (that includes reporting standards and financial oversight mechanisms; compulsory data exchange between banks and investigative services; and special authorities to coordinate investigations), the EU can export this to its eastern neighbourhood.

Ultimately, cyber security authorities and financial oversight bodies will only foil foreign covert operations where local law enforcement agencies arrest the right culprits, confiscate their assets, and close illicit cover organisations. In this, it is troubling that Eastern Partnership states are at the lower end of the World Bank’s Government Effectiveness Estimate: Ukraine (-0.46) and Moldova (-0.53) fall well below the global average; only Georgia (+0.58) has seen significant improvements since 2005, putting it roughly on the level of Greece (+0.31). But there is a large gap between these countries and, for example, Germany (+1.72).

All Eastern Partnership states suffer from overlap and conflict between the competences of their investigative and law enforcement agencies; low salaries in the public sector (which increase institutions’ vulnerability to corruption); opaque procedural laws; complicated, bureaucratic investigative procedures; criminal codes replete with loopholes and contradictions; little to no institutional cooperation between law enforcement bodies; hierarchical, centralised structures in which a few high-ranking decision-makers can block or foil investigations in entire service branches; and significant political control over investigative bodies. There have been few deep reforms of the Eastern Partnership’s investigative and law enforcement agencies. And, where such reforms have occurred (as they did under interior minister Vano Merabishvili in Georgia or prosecutor general Ruslan Ryaboshapka in Ukraine), they have been subject to intense campaigns of obstruction and defamation by local business elites and established political forces. Without intense pressure from abroad, even minor reforms would not have taken place.

Given the Trump administration’s lack of interest in rule of law issues, the EU needs to prioritise its demand for security sector and judicial reform in Eastern Partnership countries. The EU also needs to create tools for providing direct support to these states, including:

- Initiatives such as the EU Advisory Mission in Ukraine (EUAM), which provides experts to evaluate reforms in detail, comment on and revise draft legislation, supervise implementation, and liaise with the authorities and civil society groups on the ground. Security sector reform is a highly technical matter that requires in-depth knowledge, as well as professional experience of implementation. One cannot reasonably expect diplomats to provide such technical assistance.

- Task forces comprising investigators, prosecutors, and judges – which the EU could send to Eastern Partnership countries not only in an oversight, advice, and assistance capacity, but also to provide impartial investigative and judicial capabilities in politically sensitive cases. Such cases have had a particularly corrosive effect on the political culture and professional integrity of Eastern Partnership countries’ judicial systems, not least where they concerned former top officials or powerful oligarchs.

In a contested environment such as the EU’s eastern neighbourhood, the intelligence and security sectors are key. Without trusted and effective intelligence, Eastern Partnership states have no chance of withstanding Russia’s destabilising operations. By constantly monitoring the threat situation, intelligence agencies play a central role in both informing decision-makers about hostile operations and tipping off law enforcement and financial security services to investigate and prosecute culpable individuals and networks. The problem is that Eastern Partnership countries’ domestic intelligence services are either unreliable because they are effectively part of the political system (making them vulnerable to corruption and abuse for political and economic gain) or have only weak capabilities.

Therefore, the EU needs to urgently support reform in, and devise capacity building programmes for, Eastern Partnership countries in these areas. The EU should provide capacity building programmes, structural coordination on threats, technical support (particularly on cross-border signals intelligence), and military intelligence – in return for in-depth reform of the intelligence and security services. Such reform would involve increased democratic accountability, a reduction in the overlap between law enforcement agencies’ competences and procedures, and provisions designed to curtail corruption. In Ukraine, EUAM proved invaluable in liaising with local services on their needs, as well as in judging the progress (and, unfortunately, regression) of intelligence reform. Building on EUAM’s experience, the EU could appoint intelligence liaison offices in Tbilisi and Chisinau. It should create an Eastern Neighbourhood Intelligence Support and Coordination Cell in Brussels, to both coordinate assistance (as the support group does) and facilitate practical exchanges of intelligence. The EU could expand the Joint EU Intelligence School, an infant PESCO project, beyond narrow cooperation between eastern Mediterranean states – so that it covers eastern European countries in which the bloc has strategic interests. The school would then be suitable for training intelligence personnel from Eastern Partnership and Western Balkans countries.

On top of this, the EU needs to dramatically increase its own intelligence capacities in its eastern neighbourhood. Where necessary, EU member states’ intelligence agencies should compensate for shortcomings in Eastern Partnership countries’ domestic intelligence and particularly counter-intelligence services – perhaps vetting candidates for important offices, identifying hostile operations and their cover organisations early on, and anticipating power grabs by influential figures.

This is especially important in situations of revolutionary change in which new administrative and other power structures emerge – something that is still a distinct possibility in all Eastern Partnership countries. These situations provide Russia with an opportunity to use its networks of front organisations to place allies in new structures and foil reform efforts from within. The EU has been too reactive in these scenarios, leaving it unable to effectively monitor the development of the situation and the people driving change. Of course, there is always a significant chance of miscalculation in a turbulent environment. But the EU’s lack of proper intelligence precludes success. In the past, the bloc has often made up for this by relying on American intelligence.

Moscow sees covert operations as the main way to destabilise governments and expand its influence. Yet it also disrupts them in more overt ways. As depicted in the pyramid above, Moscow uses open threats to a country’s territorial integrity and sovereignty to intimidate governments. Even without invading other countries, Russia sometimes uses a military show of force on the border of neighbouring countries to underscore its escalation dominance and thereby influence their decisions. For example, in March and April 2014, Russia massed three operative manoeuvre groups on its border with Ukraine. Fearing an outright invasion, Ukraine deployed the very few combat-ready military forces it had at its disposal to defensive positions close to Kyiv and the west bank of the Dnieper, and refrained from a military response to Russian special operation services’ takeover of government buildings and establishment of separatist structures in eastern Donbas.

Some European diplomats believe that turning Eastern Partnership countries into non-aligned or neutral states would help stabilise the region. However, this would not happen automatically – and Moscow would be unlikely to respect such non-alignment. Indeed, non-alignment would only be a viable option for Eastern Partnership countries if they strengthened their capacity to defend themselves from external subversion.

There is an urgent need to decrease Eastern Partnership countries’ vulnerability to the threat from proxy forces such as those in Moldova and from the Russian military in Georgia and Ukraine. Of course, it is difficult to imagine a situation in which Eastern Partnership states would be immune to military attacks from a large, nuclear-armed regional power such as Russia. But their objective does not have to be total immunity. Like many non-aligned states during the cold war, they should make military preparations designed to convince potential aggressors that military aggression would come at too high a cost. Ukraine showed the value of this approach in 2015 and 2016. Russia theoretically maintained escalation dominance in Ukraine (an issue often fetishised by opponents of stronger military aid for the country), but any further escalation would have necessitated a much greater Russian effort – one that the Kremlin would have struggled to justify to its domestic audience. Nonetheless, the Ukrainian case also showed that the issue of increasing the effectiveness of a country’s armed forces is about not just equipment but also comprehensive, long-term engagement in military and defence-industrial support.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the armed forces of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine were neglected, ill-equipped, and undertrained, while their leadership ethos, techniques, and combat procedures were still based on Soviet doctrines and principles. As a result, the Russian military could largely anticipate what its opponents would do in every contingency. Moreover, Eastern Partnership countries’ command and control equipment had not changed much since the demise of the Soviet Army. This meant that Russia could – in the initial stages of the war in Ukraine and with second-line forces in Georgia – intercept their communications. Accordingly, to the Russian military they were an open book. This vulnerability persists in much specialised equipment – including air-defence systems, coastal surveillance systems, airspace surveillance radars, and artillery spotting sensors.

Georgia tried to re-educate its military personnel in the Western way of war by contributing to as many Western military missions as possible (including those in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Kosovo) and by trying to acquire US military support that would enable such participation. But international missions and counter-insurgency warfare are very different from the defensive combined-arms operations that Georgia’s army was supposed to undertake to defend the country against its Russian counterpart. As such, this experience was of little help when the war in Georgia erupted in 2008.

The problem is also apparent in European-led exercises and training missions that include Eastern Partnership countries, which usually focus on “soft” security issues such as counter-terrorism, maritime security, or disaster relief and humanitarian operations. These are not the areas that Eastern Partnership states are most interested in.

In 2015 the US, the UK, and Canada started a bilateral initiative in Lviv to train Ukrainian battalion and company commanders in Western combat and leadership techniques (Poland and the Baltic countries later joined the effort). This mission may come to be regarded as much a success in helping NATO officers understand Russian war-fighting tactics as in bolstering Ukraine’s campaign in Donbas.

The initiative could serve as a template for a broader EU training and leadership support effort to professionalise Eastern Partnership countries’ armed forces. The EU could admit a certain number of Eastern Partnership states’ junior officers to the Military Erasmus Programme. It could also fund further training for young officers in one of Europe’s many military academies. The EU should send experts to Eastern Partnership countries to refine their military training curriculums and to modernise and Westernise those for officers of all kinds. It should complement the effort with command post exercises and war games, as well as common manoeuvres for all armed forces, to prepare for various contingencies in the region (US forces in Europe frequently conduct such manoeuvres with Ukraine).

Assistance in comprehensive defence planning is especially necessary for Georgia and Moldova. As Moldova does not directly border Russia and separatist forces in Transnistria present a different threat to conventional Russian military units, the Moldovan army needs to develop into a high-readiness, mobile force that coordinates well with the police to quickly counter hybrid threats. Georgia, in contrast, is particularly vulnerable due to its geographical position, with sizable Russian military forces deployed on its territory and across the border. Georgia’s defence policy has undergone a chaotic series of shifts and restructurings – with its holistic concept for territorial defence (comparable to that in Sweden, Finland, and the Baltic countries) still in the early stages of implementation. Because the Soviet Army was never organised for territorial defence, Eastern Partnership countries inherited no tradition of thinking in this area.

Similarly, international operations such as the NATO mission in Afghanistan do not resemble, or help forces prepare for, territorial defence per se. The little training and advice that Eastern Partnership countries do receive from the EU (as envisioned under Association Agreements) are designed to facilitate their participation in EU-led missions or battlegroups. This may help the EU recruit staff for its missions, but it hardly makes it easier for Eastern Partnership countries to develop the armed forces they need. While, for example, the Visegrad battlegroup regularly includes Ukrainian and Georgian soldiers, it is unclear whether EU battlegroups have a practical use.

In their approach to defence reform in Eastern Partnership countries, the EU and NATO should primarily focus on territorial defence rather than preparation for international missions. The Lithuanian-Polish-Ukrainian brigade may serve as a template for joint EU- Eastern Partnership training designed to address full-spectrum warfare. Although this partnership is facilitated by geography, more distant EU member states could still strengthen their ties with Eastern Partnership countries through officer exchanges, common exercises, or efforts to share training facilities.

Finally, there is the issue of the technical and technological modernisation of Eastern Partnership countries’ armed forces. This is a long-term endeavour that requires considerable investment in military procurement, as well as in the defence industry. Due to the high costs of Western defence technology, some post-communist NATO armies in central Europe retain much of the equipment they used during the cold war. And financial considerations are even more of a barrier for Eastern Partnership countries. Hence, Europe should create a foreign military aid programme similar to that established by the US – under which Eastern Partnership countries could apply for cheap loans to purchase European defence goods, in cooperation with European defence planners. The EU could supplement this effort with a neighbourhood defence support fund.

Many European countries have reservations about supplying advanced weapons systems to Eastern Partnership countries, due to concerns about corruption and possible compromise by Russian intelligence agencies. This is especially true of systems for air defence; electronic warfare; command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; and weapons guidance. And, while Eastern Partnership countries would like to join defence-industrial cooperation programmes in Europe, many EU member states do not want to allow them to do so. This is because Ukrainian firms would directly compete with domestic ones such as EADS and MBDA. For these member states, European defence-industrial cooperation is a form of protectionist hedging.

The EU could tackle these problems by launching a special Eastern Neighbourhood Defence-Industrial Cooperation Programme. The aim of the initiative would be to produce systems that combined Ukrainian know-how and defence products with European components. These components would be sufficiently Western to resist Russian countermeasures but not so Western as to pose a threat to system integrity if they were captured or compromised by Russia’s intelligence agencies. Incorporating Eastern Partnership countries into the supply chain would decrease the price of these products – which would also be suited to foreign military aid programmes in the Middle East and Africa.

Last but not least, the EU faces challenges related to Eastern Partnership countries’ energy security. In an ideal world, energy transit would enable constructive cooperation between Russia, the West, and Eastern Partnership states: Russia depends on cheap and secure facilities for exports to Europe; Europe needs reliable sources of energy (both oil and gas); and Eastern Partnership states want to earn transit fees by connecting the two. But – due to the crises over gas transit through Ukraine that erupted in 2006 and 2009, as well as fears that some member states’ high dependence on Russian gas, oil, and electricity makes them vulnerable to blackmail – the EU has started to implement a common energy policy. In general, the policy is designed to create a transparent, interconnected, and competitive domestic market for energy that breaks up certain energy companies’ monopolies and diversifies supply. The legal framework of this energy policy has developed into foreign policy, as neighbouring states can join the EU energy community by adapting the bloc’s rules and governance structure to their energy markets. Inclusion in the larger EU market should decrease the cost of energy for Eastern Partnership countries (some of which currently have to pay among the highest prices for natural gas in Europe) and should significantly strengthen their hand in negotiations over energy purchases.

There has been some progress in this area: Georgia is now much better connected with neighbouring countries and has diversified its supply; Ukraine has implemented painful reforms to its domestic energy market and pricing regulations, while breaking up monopolies and eliminating corruption schemes that proved to be a major political liability. Yet Moldova’s attempts to connect with the Romanian gas market were cut short when a pro-Russian government came to power in November 2019.

However, in the coming years, the bigger issue on energy transport will concern whether Eastern Partnership countries will play any role in energy transfer, or whether Russia will be able to circumvent the region as a whole by completing the TurkStream and Nord Stream 2 pipeline networks. Eastern Partnership countries fear that, if it no longer needed other post-Soviet states (especially Belarus and Ukraine) for energy transit, Russia would be freed of a major constraint on its attempts to bully and intimidate them – including through the use of military force. Last year, Russia and Ukraine averted a showdown on the latter’s role in gas transit only at the last minute, reaching an agreement that runs until 2024 and sets a minimum level of annual gas transit to maintain energy infrastructure in Ukraine.

While the EU mediated the negotiations as a broker, the US was the true facilitator of the agreement. Pending US sanctions on new Russian gas pipelines (which primarily target Nord Stream 2 but may also complicate the maintenance of TurkStream) made it risky for Russia to circumvent eastern Europe entirely. Given that there was a growing consensus in Washington about the need for these sanctions, and that Germany had little support within the EU for Nord Stream 2, Russian President Vladimir Putin needed to hedge against possible future developments. Maintaining a minimal gas-transit role for Ukraine was part of that hedging process. Hence, Russia has postponed its ultimate decision on the transit issue – and the dispute is likely to continue for some time.

How to improve EU decision-making and unity on the Eastern Partnership

The EU is unlikely to become a unified geopolitical actor in the coming years. But, even without doing so, the bloc can achieve much through the development of new regulatory frameworks in areas such as money laundering, cyber security, the media, and defence exports. And, by adhering to the “more for more” principle, the EU can condition its assistance to Eastern Partnership countries – and their access to its programmes – on the adoption of such regulations.

Of course, the recent setback in funding for PESCO and European Defence Fund projects under the EU’s new financial framework casts doubt on its ambitions in these areas. The EU seems to have grown more introverted, divided, and modest in its ambitions, almost abandoning foreign policy in the wake of the 2015 refugee crisis and the coronavirus pandemic. However, this trend is not irreversible – yet.

One of the trickiest issues in the area is that of common structures. Member states retain control of almost all the EU’s collective intelligence, police, and judicial capabilities. This is particularly apparent in intelligence, a realm in which coordination between them is sporadic and lacks a coherent institutional underpinning. Given the big capability and competence gaps between member states’ intelligence services, and the fact that some of them have likely been penetrated by their Russian counterparts, structured cooperation between these services would require very careful, detailed planning. Either the European Council would have to establish a new, centralised intelligence agency that worked under the External Action Service, or a few capable and reliable member states would have to create a broader Eastern Partnership intelligence cell, as part of a PESCO coalition of the willing.

This would coordinate not only intelligence efforts but also member states’ bilateral military and police assistance programmes. A “European Security Compact” – either as a PESCO initiative or, like the Support Group for Ukraine, one working under the European Commission – would coordinate support for defence and intelligence reform projects, provide access to EU funds for such projects, liaise with Eastern Partnership states on the assistance they require, and evaluate the progress they made. The initiative could also cover joint planning, command post exercises, and war-gaming – involving comprehensive crisis response mechanisms – to test, evaluate, and refine its concepts and structures. It would also be advisable for the EU to replicate EUAM (which has already proven to be a useful tool) in Tbilisi and Chisinau. All these steps would be feasible within the EU’s current budgetary and legal frameworks. However, they require the political will to act.

The EU appears to have reached a consensus that, if it wants China to take it seriously, it will need to establish a position of strength in their economic relationship. The EU has not yet applied this lesson to its efforts to deal with Russia at home and in its eastern neighbourhood, but the basic rationale for doing so is the same. While many European diplomats and other officials may simply dismiss the prospect of the EU becoming a security enabler, the rest of the world will hardly be forgiving of flaws in the bloc’s organisational culture and policies. The EU has never had a military dimension to its identity or organisational culture, but establishing one is a prerequisite of strategic sovereignty. A strategically sovereign actor must deal with all dimensions of state power – even those that make it uncomfortable.

Thus, EU cohesion still has a lot of room for improvement. The geopolitical debate within the bloc is overshadowed by north-south and east-west struggles over priorities and resources. So far, it has been easier for EU member states to block or weaken proposals that would be beneficial to others than to gain support for their own projects. This system of mutual deadlock does not serve European interests in Eastern Partnership countries (nor in the Mediterranean). Larger member states continue to complain about a lack of support for their projects from smaller states, which eye these sometimes unilateral initiatives with ever-growing suspicion.

The dynamic can be seen in two recent developments: French President Emmanuel Macron’s push for a new European security order and Germany’s proposal to complete Nord Stream 2. In each case, the domestic political establishment has insisted that the initiative is in the interests of Europe as a whole. But very few EU capitals see it this way. As Macron has yet to lay out the concrete terms, conditions, red lines, and desired end state of his proposed security order, the effort has elicited a cautious, suspicious response from eastern and Scandinavian member states. For now, the initiative has not resulted in any tangible steps that they need to respond to – but this may well change. If it does, they will likely seek support from Washington in pushing for a more conservative stance on Europe’s security order.

Meanwhile, even supposedly pro-Russian countries such as Italy and Bulgaria oppose Nord Stream 2. Although Germany could muster a small blocking minority to thwart attempts to halt the project, security concerns have led some member states to count on pressure from US sanctions to prevent the completion of the pipeline.

With both Germany and France now strong advocates of European strategic sovereignty, the two countries need to reconcile their ambitions with the security interests of other member states. Efforts to protect Franco-Iranian deals or German-backed pipelines from US sanctions are not the basis for the kind of strategic sovereignty that would benefit Europe. (Nor is the desire to shift the production of medical goods from China to Europe.) To become real and relevant, European strategic sovereignty needs to be multidirectional – which means that it must cover Eastern Partnership countries.

It is no easy task to exchange mutual deadlock for mutual support on strategic issues. However, member states can start to achieve this by acknowledging that:

- Some of them have special experience and expertise in dealing with various EU partners. Eastern European and Scandinavian member states should generally trust France, Italy, and Spain on issues involving the Mediterranean, Iran, or the Middle East peace process. And France, Italy, and Spain should pay heed to eastern European and Scandinavian countries in anticipating Russian moves and interests, as well as in dealing with Eastern Partnership countries.

- EU member states should consult one another in Brussels in advance about their planned moves and policies that relate to strategic sovereignty, to spare them unpleasant surprises.

- Member states need to expand the EU’s portfolio in key areas – as they have done throughout the bloc’s history. France and other Mediterranean countries should agree to increase EU resources and operations in Eastern Partnership countries; in return, Scandinavian and eastern European member states should make a greater contribution to French missions in Africa, maritime security operations in the Mediterranean, and other initiatives. France should support Scandinavian countries in resisting Russian revanchism; Scandinavian countries should support France in resisting Turkish revanchism. They should frame all this as a defence of the legal status quo of the European security order.

- The European Commission’s role should be strengthened to avoid protracted bilateral disputes between EU member states. For example, had Germany allowed the European Commission to take responsibility for negotiating and launching new pipeline projects, other member states might now be more willing to help such initiatives resist external pressure.

In theory, the merits of these recommendations should be self-evident to European leaders who seek to create a cohesive EU foreign policy. Member states may have long lived in a permissive environment for unilateral action within the EU, but the world is changing fast. The EU finds itself in an increasingly hostile geopolitical environment – one in which the non-confrontational security policies the bloc favours are less effective than they once were. Other powers are relatively unconcerned about European security, diplomatic, or political interests. Indeed, the last decade has seen Russia, China, Iran, and Turkey all become more assertive vis-à-vis the EU.

Therefore, if the EU wants to be strategically sovereign, and to make its voice heard on the global stage, it will need to behave more assertively. This will require the bloc to strengthen its alliances and security partnerships with neighbouring countries – and to be less reluctant to change the behaviour of other powers.

About the author

Gustav Gressel is a senior policy fellow with the Wider Europe Programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations, based in the Berlin office. Before joining ECFR he worked as a desk officer for international security policy and strategy in the Bureau for Security Policy in the Austrian Ministry of Defence and as a research fellow for the Commissioner for Strategic Studies in the Austrian Ministry of Defence. He also worked as a research fellow at the International Institute for Liberal Politics in Vienna. Before beginning his academic career, he served in the Austrian Armed Forces for five years.

Gressel earned a PhD in strategic studies at the Faculty of Military Sciences at the National University of Public Service, Budapest, and a master’s degree in political science from Salzburg University. He is the author of numerous publications on security policy and strategic affairs and is a frequent commentator on international affairs in German and international media.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.