Europe’s pandemic politics: How the virus has changed the public’s worldview

Summary

- As covid-19 raged, speculation grew that the crisis would restrengthen public support for the state; faith in experts; and both pro- and anti-Europeanism.

- New research reveals these all to be illusions. Instead, the crisis has revolutionised citizens’ perceptions of global order – scrambling the distinctions between nationalism and globalism.

- One group – the DIYers – sees a nineteenth-century world of every nation for itself; the New Cold Warriors hear echoes of the twentieth century and look to Trump’s America to defend them from China; the Strategic Sovereigntists foresee a twenty-first-century world of blocs and regions.

- This last group are the largest and represent a new form of pro-European who believe Europe will need to support its own sovereignty through joint foreign policy, control of external borders, and relocalised production.

- This moment represents a new opportunity for European cooperation – but the continent’s leaders must make the case carefully to avoid provoking a backlash of reintensfied Euroscepticism.

- Rather than a ‘Hamilton moment’ of proto-federalisation, we are instead living through a ‘Milward moment’ of strong nation state identities searching for protection in a dangerous world.

Introduction

The covid-19 crisis is probably the greatest social experiment of our lives. We do not know when or how it will end. It is still too early to predict how radically it will change the way Europeans see their own societies. But we can already see that the pandemic has transformed the way Europeans look at the world beyond Europe, and – as a consequence – the role of the European Union in their lives.

In the early stages of the crisis, politics was suspended, and public opinion fell in behind the actions of national governments. Citizens were sent into internal exile in their own homes, many paralysed with fear and uncertainty. Governments moved quickly to introduce emergency measures to stop the spread of the disease, shore up healthcare systems, and save jobs and businesses from collapse. In the next stage of the crisis, as governments raise vast sums of money to fund a recovery, they will need to take politics into account. It will not be enough to develop the right policies; governments and EU leaders will also need to find the right language and frameworks to win public support for their policies. In order to do this, they will need to understand how covid-19 has– or has not – changed publics’ fears and expectations.

To find out how the pandemic has affected European citizens’ views on politics, society, and Europe’s place in the world, the European Council on Foreign Relations commissioned a poll of over 11,000 citizens in nine countries across Europe – Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden – covering more than two-thirds of the EU’s population and GDP. The poll was conducted at a moment when most EU member states had started reopening their economies, and when the economic recovery replaced public health at the top of the policy agenda. The results of the poll call into question some of the early lessons that political commentators drew from the crisis. The emerging conventional wisdom is that covid-19 has: created a surge in public support for a newly empowered role for the state; restored trust in the role of experts; and empowered the forces of both Euroscepticism and European federalism. But the findings of our survey challenge all three of these assumptions – and show them to be illusions that could lead European governments to fall foul of public opinion as they plan the recovery.

Before the crisis, the continent was increasingly split between pro-European cosmopolitans and Eurosceptic nationalists. At the beginning of the pandemic, the French president, Emmanuel Macron, warned that the virus could change the balance between these two camps in Europe, strengthening the nationalists. Several weeks into the crisis, a replacement conventional wisdom emerged that held that, actually, a federalist moment of European integration was coming into being. Perhaps confusion in the flux was understandable: ECFR’s survey shows that, rather than strengthening one camp or the other, the virus has scrambled the distinction between the two. On the one hand, many nationalists appear to have realised that European cooperation is the only way to preserve the relevance of their nation states. On the other hand, many cosmopolitans have seen that, in a world squeezed between Xi Jinping’s China and Donald Trump’s America, Europe’s best hope for preserving its values lies in strengthening its own “strategic sovereignty” rather than relying on global multilateral institutions. This new mood creates an astonishing amount of space for reviving the European project. But, unless members of the governing class across Europe dispel their illusions about what is happening, they risk squandering it.

Illusion ONE: The crisis has created a new consensus in Europe, persuading most of the public to support a greater role for the state

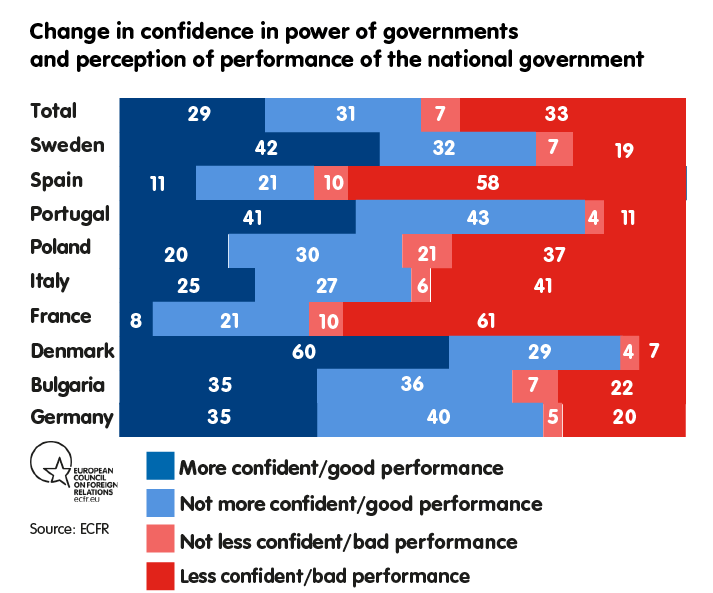

The return of ‘big government’ is a fact. But, in many places, it is not back by popular demand but rather because elites seized new powers to deal with the pandemic. Our polling shows that the number of people who have lost trust in the capacity of the government to act is larger than the number who have become keener on government intervention in the wake of the crisis. In two individual questions in our poll, we asked how confidence in the power of governments in general has changed; and how respondents assess the performance of their national government during the crisis. Across all nine European countries, only 29 per cent say they have greater confidence in the government and, at the same time, believe that their own government has done well in the crisis. In contrast, 33 per cent have lost confidence in the power of government while also holding a dim view of how their own government has performed.

While publics have been willing to go along with the state returning to the role of managing and owning large swathes of the economy, our data shows that this has not been accompanied by a wave of enthusiasm of the type seen in many countries in the 1920s and the 1940s, as governments at that time nationalised major industries. Citizens today appear to see the state less as a motor of progress than as an insurance mechanism; or, perhaps, as a warehouse for unwanted workers or for the stockpiled masks, medicines, and food that we could need in the next crisis.

Of course, these aggregate figures mask huge variations between EU member states. At one extreme is Denmark, where 60 per cent of voters both have greater confidence in the power of government than they previously did and believe their government has performed well. At the other extreme is France, where 61 per cent have less confidence in government per se and a negative perception of their government’s performance.

Studying the figures in more detail reveals that positive views of the power of government and the performance of the authorities correspond strongly with how citizens vote. Supporters of incumbent parties are, unsurprisingly, overrepresented among those who believe in the power of government and agree that their own government has done a good job. On the other hand, supporters of non-government parties largely regard their governments’ performances poorly and exhibit less confidence in the power of government. Sweden is an outlier, however: there, supporters of several non-government parties also think the government has performed well. National pride could explain this. Swedes across party affiliations appear to approve of Swedish exceptionalism in the pandemic, although this high level of support might already have changed – since our polling was conducted, the Swedish debate has become more heated as Sweden’s death count grows bigger than in neighbouring states that implemented a total lockdown.

And, when it comes to support for parties, the crisis seems to have accentuated existing trends rather than fundamentally changing politics. The polling we carried out on party support suggests that covid-19 has not fundamentally altered the balance between the political mainstream and populist challengers. When populist voters change their vote, they tend to move to another populist party, while mainstream party voters who do the same move to another mainstream party.

Overall, therefore, the coronavirus crisis has not yet created new political cleavages or cleared a path for new political actors; nor has it fundamentally changed voters’ attitudes towards the role of the state.

Illusion TWO: The crisis has led to a surge in support for experts

Millions of people have religiously followed the advice of medical experts during the lockdown, but our polling suggests that the – much-praised – return of public faith in expertise is an illusion. Unfortunately, there is no evidence to suggest an imminent return to an enlightened politics governed by facts and persuasion rather than by emotion and mobilisation.

To really delve into this question, our survey deliberately did not provide respondents with a binary choice about experts – ‘Do you trust them or not?’ – and instead offered them three options. The survey’s questions sought not simply to reveal how many people see science as beneficial to society, but also to allow us to distinguish between two different sources of distrust. The first kind is the classic lack of trust that comes from the nature of scientific investigation: the fact that experts disagree with each other. But we also found a lot of people – who are otherwise positive about the potential of scientific knowledge to solve problems – who think governments use experts to justify decisions they have already taken, rather than to inform them.

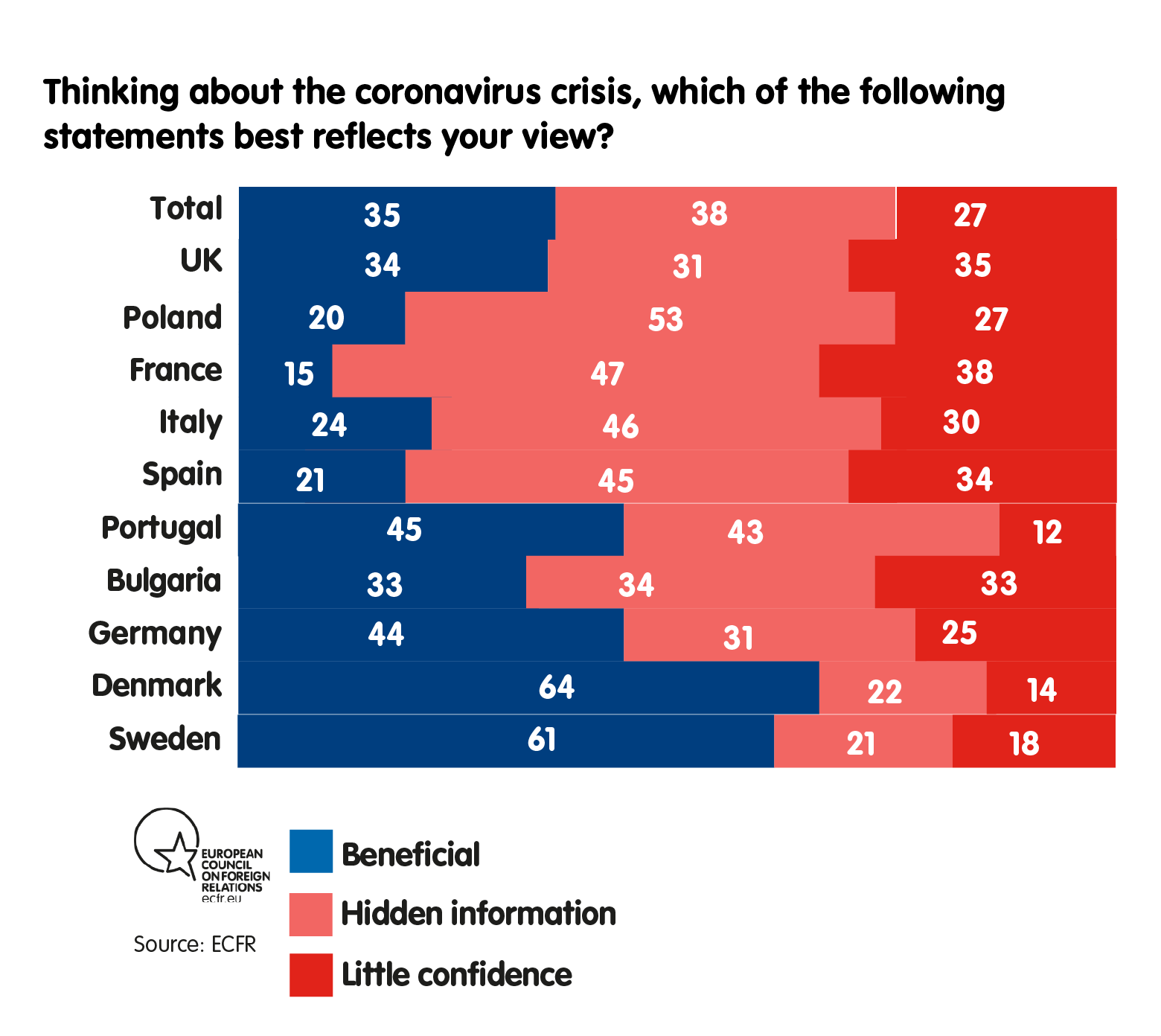

Our polling showed that a majority of citizens in most member states do not trust experts and the authorities. Indeed, it is a key finding of the poll that many citizens view experts as bound up in the political process – subject to manipulation and instrumentalisation – rather than as independent, standing apart from the political fray and providing objective truth. Among those who expressed an opinion on the issue, only 35 per cent of respondents believe experts’ work can be beneficial to them, while 38 per cent believe politicians have instrumentalised experts and concealed information from the public, and 27 per cent profess little faith in experts in general.

Again, there are great differences between member states. Confidence in experts is strongest in Denmark (64 per cent) and Sweden (61 per cent) and lowest in France (15 per cent), Spain (21 per cent), and Poland (20 per cent). People are most likely to believe that experts have been instrumentalised in Poland (53 per cent), France (47 per cent), and Italy (46 per cent).

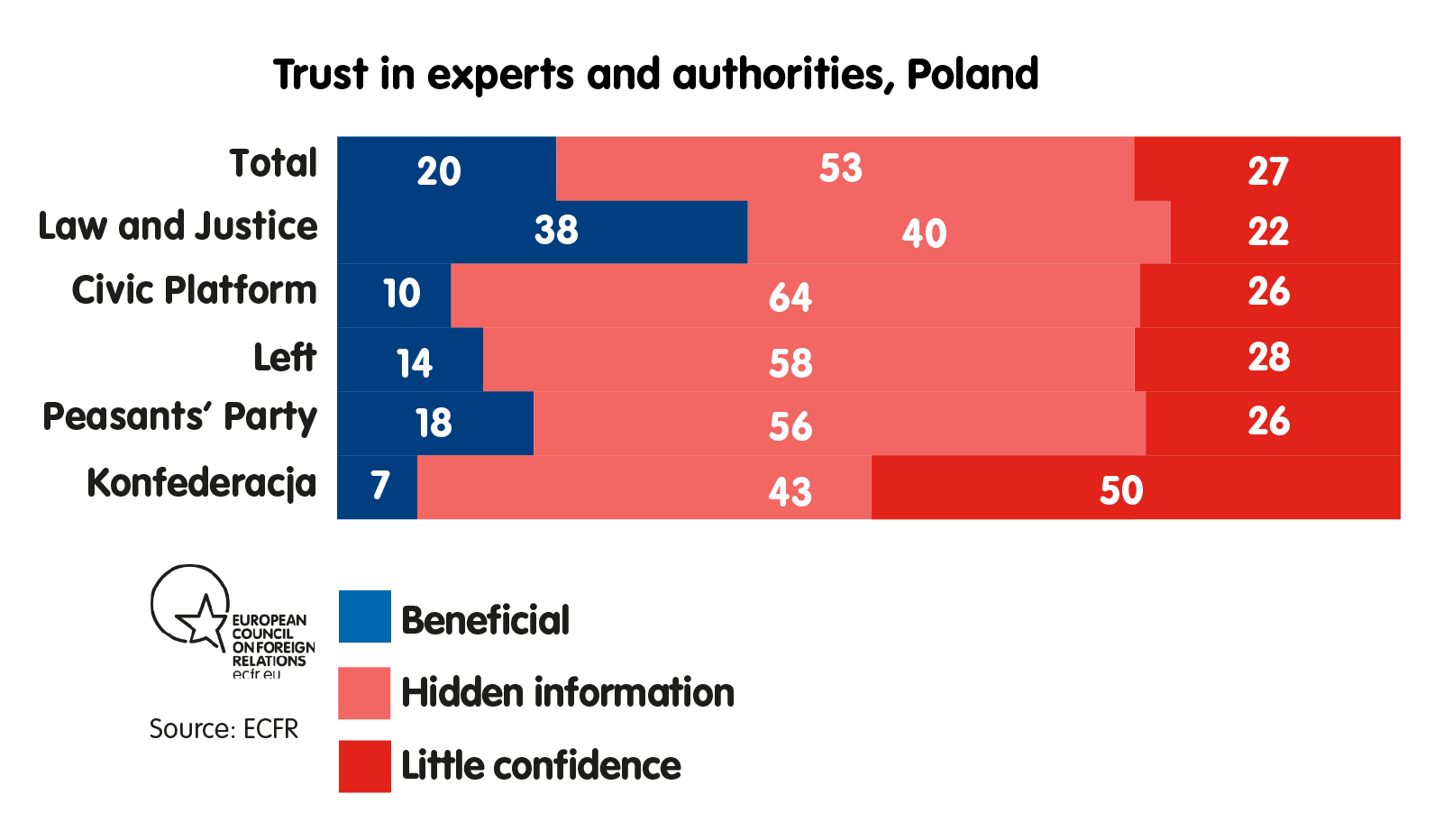

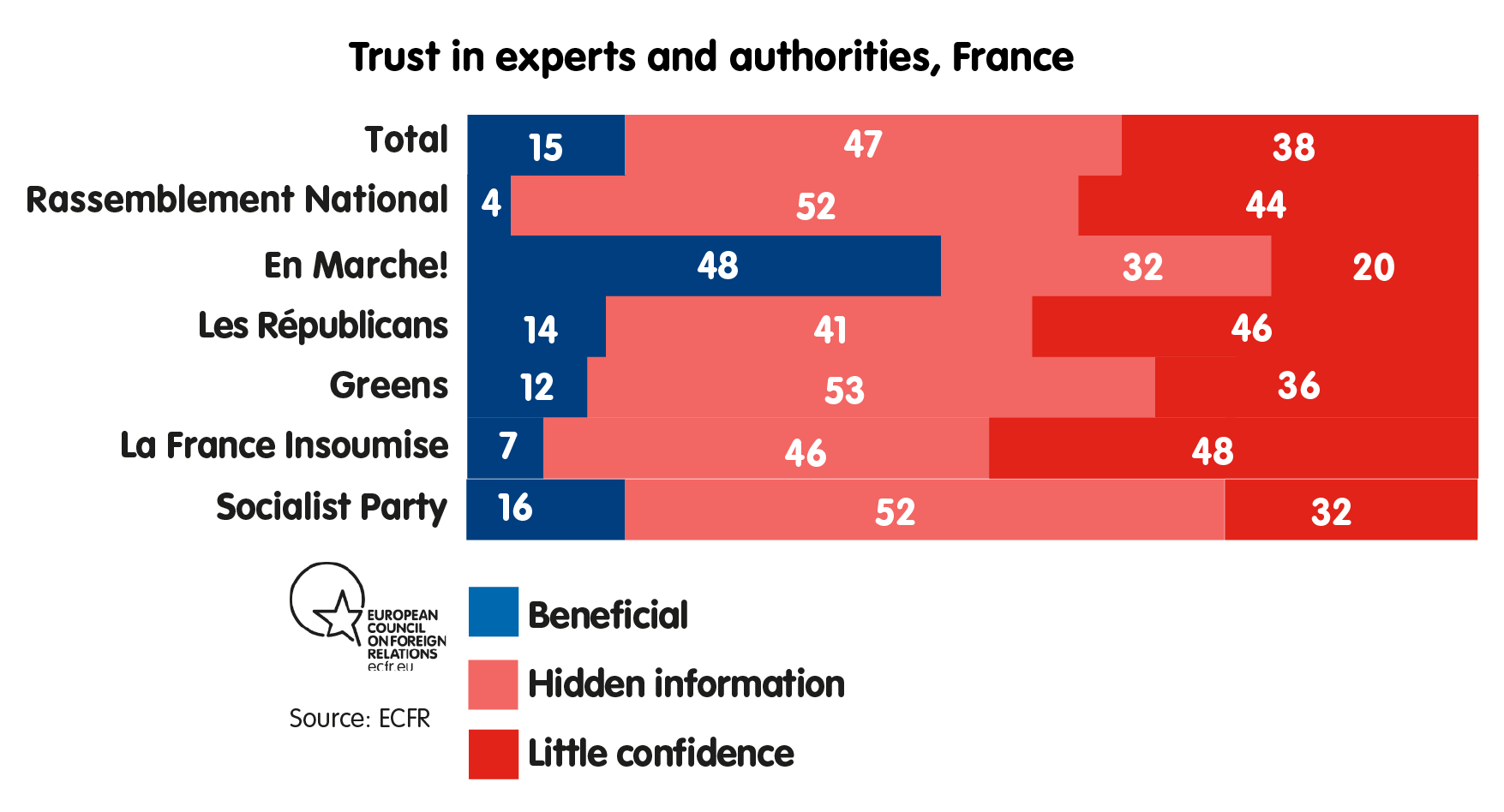

There are notable variations along party lines. In Germany, majorities of mainstream party supporters trust in experts. Around half of Christian Democrat/Christian Social Union voters (51 per cent), Social Democrat voters (48 per cent), and Green voters (56 per cent) believe that the crisis has shown how the rest of us can benefit from the knowledge of experts and authorities. In France, trust in experts is high only among supporters of Macron (48 per cent). Other French voters either have little faith in experts or believe that experts have been instrumentalised (52 per cent of Socialist Party supporters and 53 per cent of supporters of the Greens believe that experts and the authorities conceal information from the public). In Poland, those who vote for the liberal Civic Platform are a classic example of well-educated constituencies who might be expected to trust experts. But, in our poll, a majority of Civic Platform supporters do not trust experts, presumably because they think they are instrumentalised by a government that they do not support. It is, therefore, the trust that citizens have in the government that guarantees their trust in experts – and not the other way round.

The obverse is also true. Only a small number of populist voters believe that the work of experts is beneficial (6 per cent of Alternative for Germany supporters; 4 per cent of Rassemblement National supporters; 12 per cent of League supporters; 3 per cent of Vox supporters). This distrust may also explain why the biological epidemic has been accompanied by a digital epidemic of disinformation and fake news, as voters cast around for ‘experts’ they feel have not been instrumentalised by the authorities. Because the pandemic is a colossal disaster without a clear villain, it is unsurprising that it has provoked a stream of conspiracy theories. There are many theories about who is responsible for the spread of the virus. But the most radical theories question whether it even exists, postulating that the coronavirus may be a scheme devised by the distrusted elites and designed to allow them to accumulate extra powers and control over others.

Illusion THREE: The crisis has led to a surge in both nationalist Euroscepticism and pro-European federalism

When the crisis first struck, many people worried that it would unleash a Eurosceptic moment. The first reaction of many governments in the EU was to close their countries’ borders and introduce export controls – sometimes, even in contradiction to the rules governing the single market. Earlier tensions between northern and southern EU member states also rose rapidly to the surface. In fearing the rise of nationalism, many commentators tended to see parallels between covid-19 and the refugee crisis. But the nationalism triggered by the refugee crisis was an ethnic nationalism, while the nationalism of covid-19 responses is territorial, based on residency. During the most virulent days of the pandemic, governments treated migrants in the same way as residents, while compatriots returning from abroad were treated as aliens and put into quarantine regardless of their citizenship.

So, while the refugee crisis divided society between nationalists and pro-Europeans, our survey suggests that this crisis scrambled the difference between the two. The polling data is, at first glance, paradoxical.

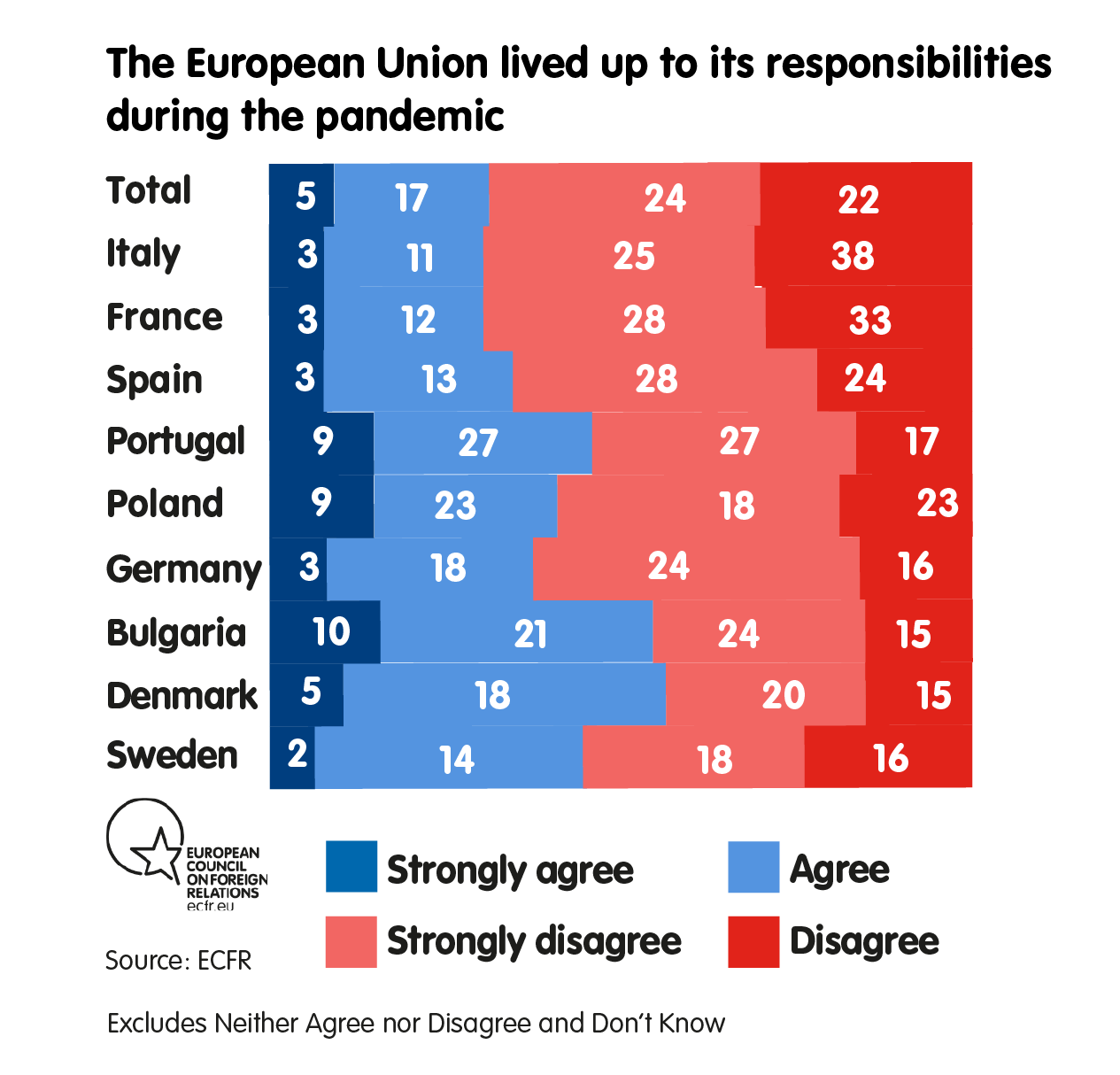

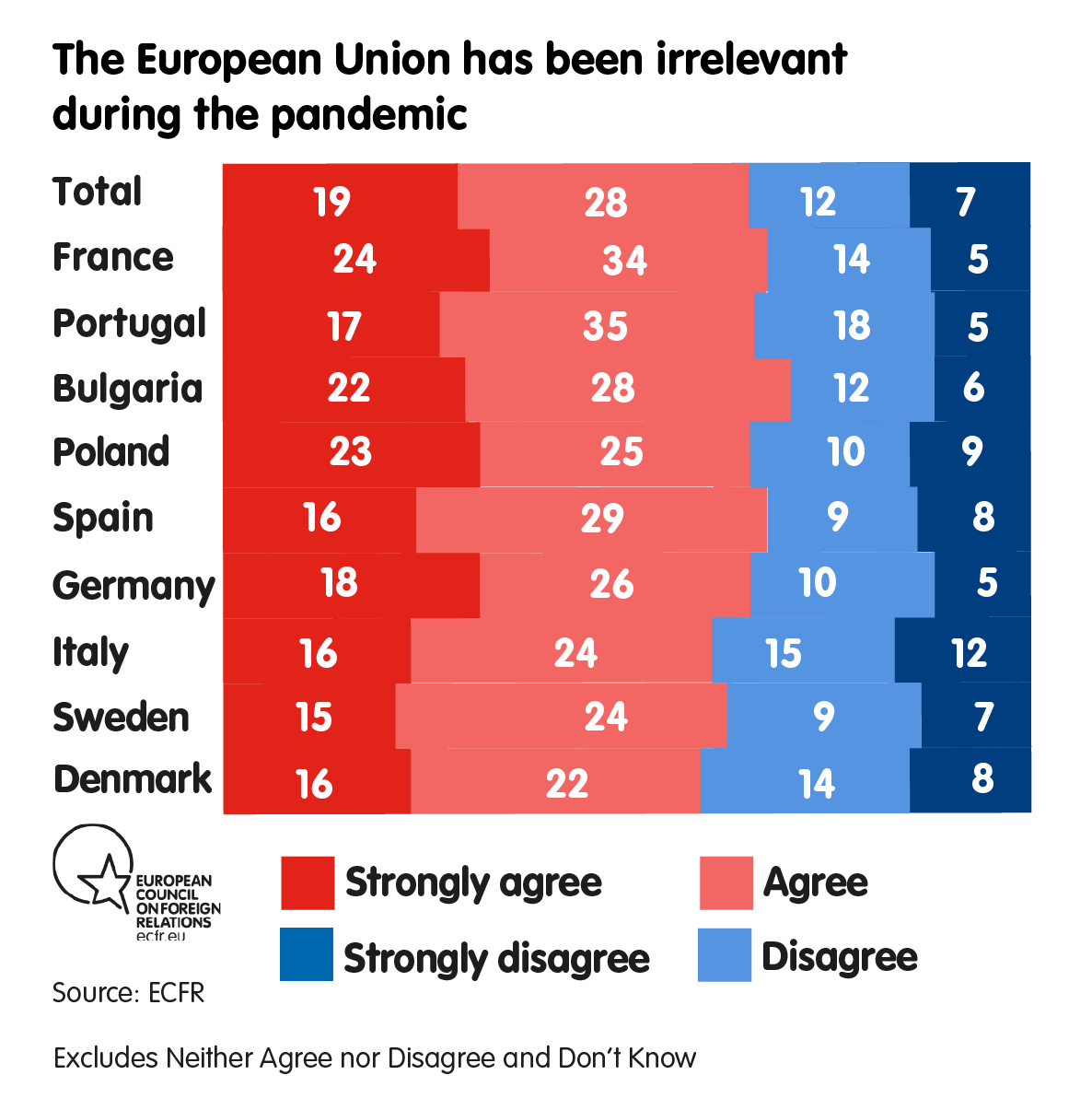

On the one hand, we can see that people in all surveyed member states believe the EU responded poorly to the crisis – with majorities in all countries saying that the EU did not rise to the challenge. This includes 63 per cent in Italy and 61 per cent in France. In a separate question, we asked whether respondents’ attitudes towards EU institutions had worsened during the crisis. Majorities in Italy, Spain, and France confirmed that it had (58 per cent, 50 per cent, and 41 per cent respectively). Perhaps more worrying than the large numbers who say the EU performed badly are the even larger numbers who say the EU has been irrelevant. In every country, more people believe this than believe the opposite – for example, more than half of respondents in France believe that the EU has been irrelevant.

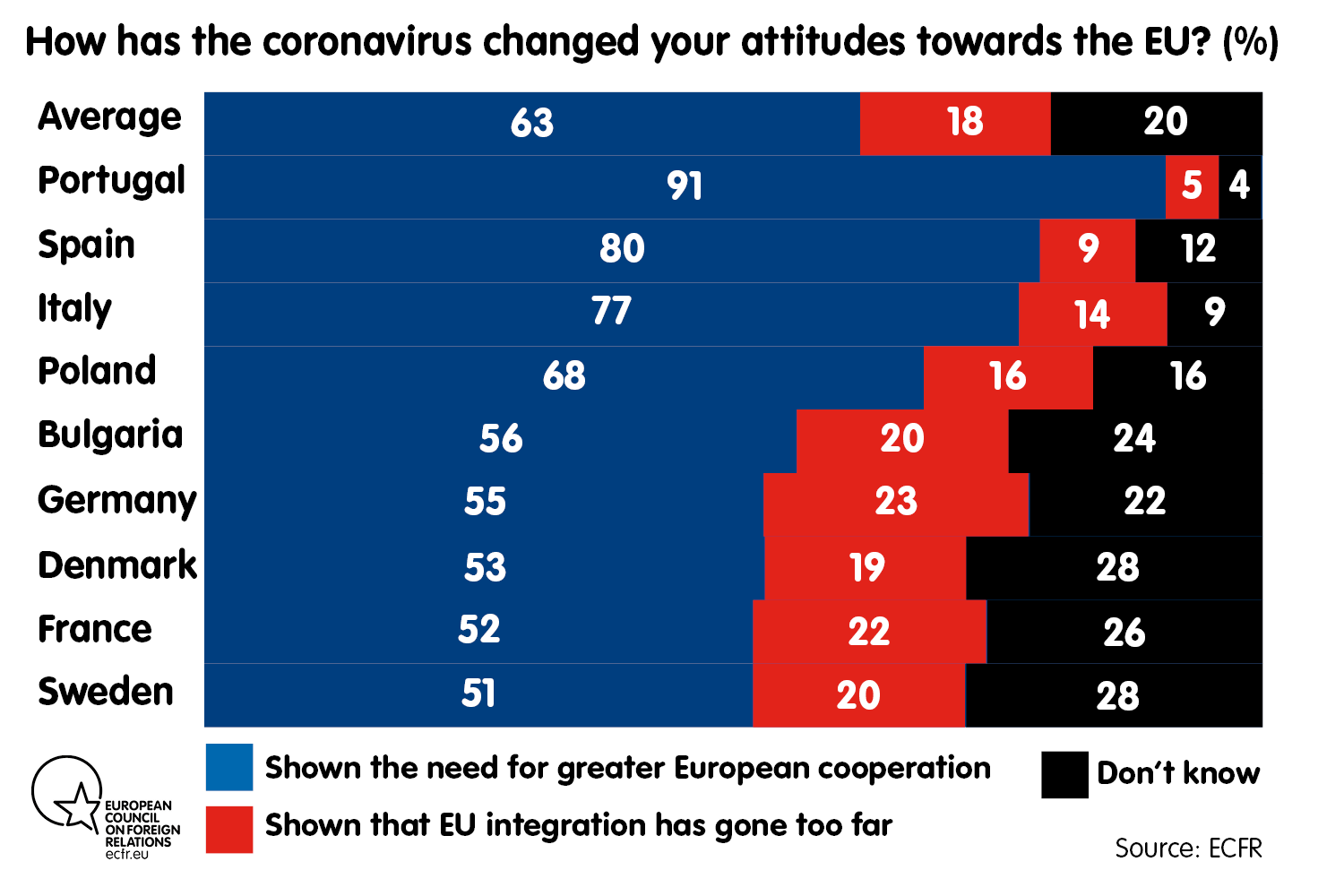

On the other hand, large majorities of people in all surveyed countries say that they are now more firmly convinced of the need for further EU cooperation than they were before the crisis. And while our 2019 Unlock polling found that there was often a reverse correlation between trust in national governments and trust in EU institutions, that was not the case this year. Last year, we discovered that many people who had little faith their national political systems saw the EU as the cure to the national disease. However, aside from people in Poland, those who expressed confidence in the power of governments to manage issues that affect their lives are even more supportive of closer EU cooperation than their national average. They appear to have learned that the nation state matters but, at the same time, in the words of the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, “the nation state has no future standing alone”.

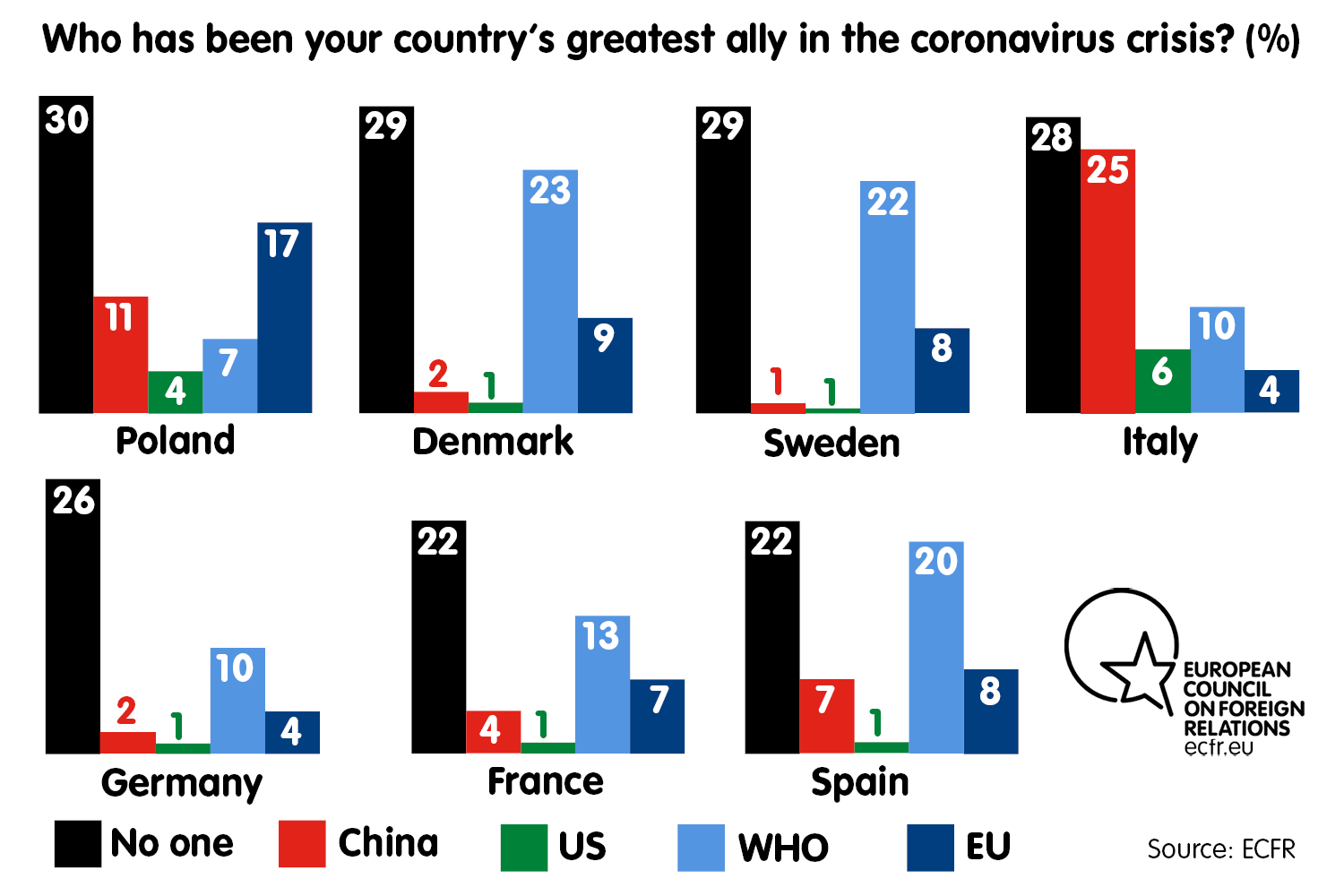

One clue to explaining this may come from the way that the crisis has given citizens the sense that their states are being left alone in an increasingly dangerous world. We asked citizens which other countries or organisations gave support and solidarity to their country as the crisis unfolded. The figures are disturbing. Large majorities felt that no one was there to help them – with very low numbers agreeing that either the EU, multilateral institutions, or Europe’s biggest economic partners lent support.

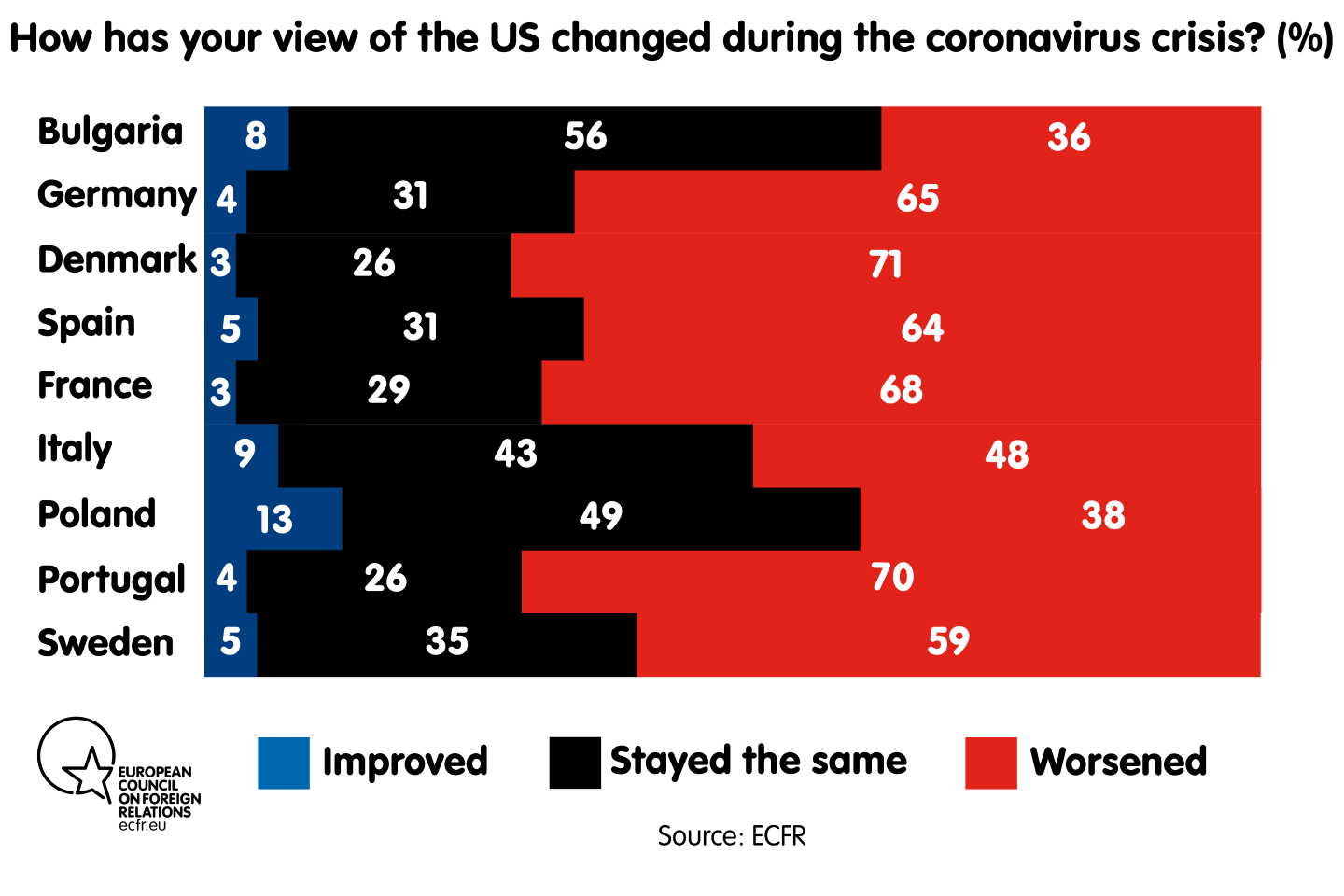

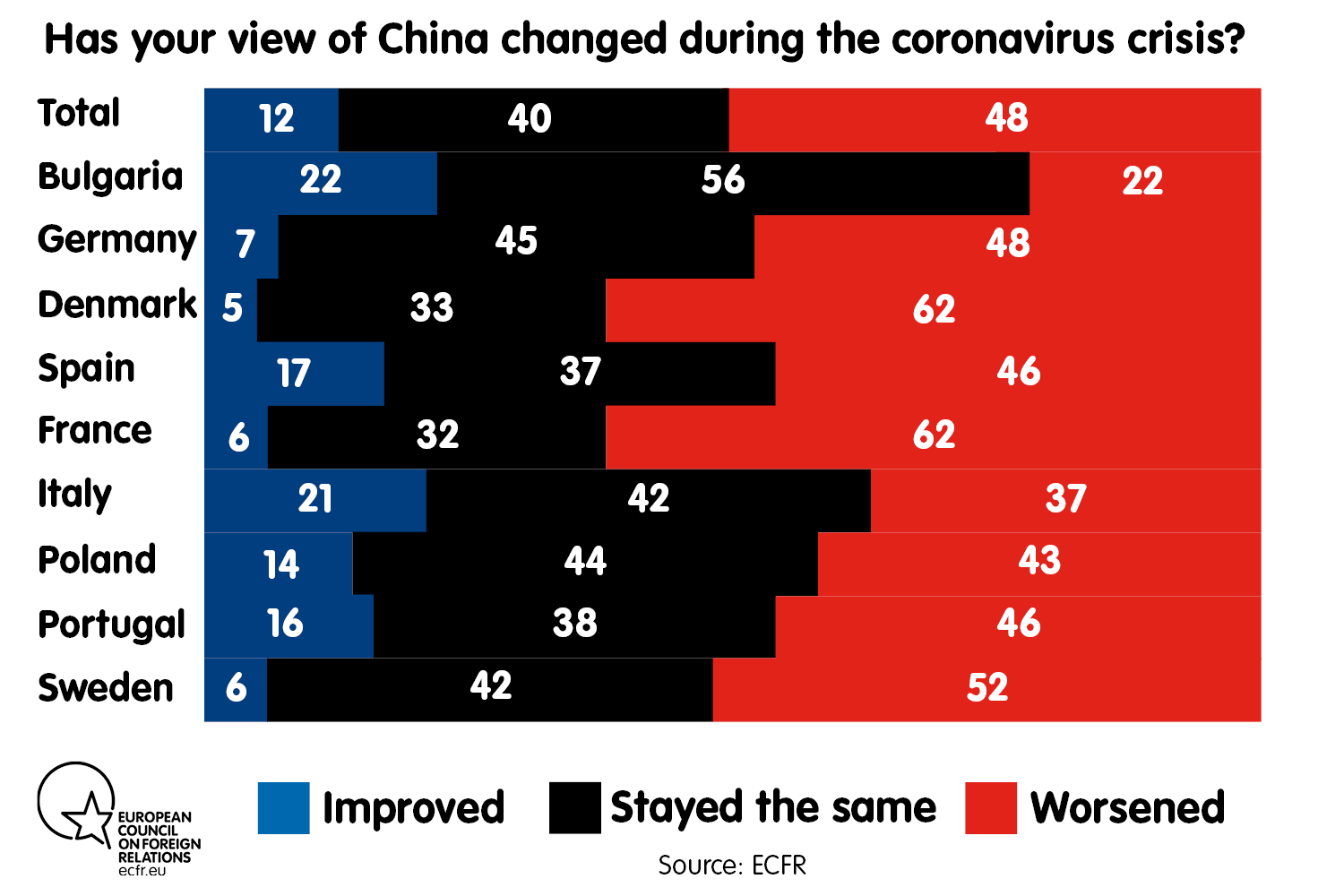

The crisis also seems to have inflicted dramatic and lasting damage on the reputations of Europe’s two biggest economic partners: the United States and China. Each superpower has seen its reputation collapse in some of the countries that were its closest allies and partners.

In the case of China, more than 60 per cent of French and Danish citizens claim to have cooled on Beijing – while almost half of Germans say the same thing. It seems that Europeans’ attitudes may have worsened because of the origins of covid-19 and the aggressive way that China has treated other countries in its response to the crisis – with disinformation, bullying, and threats to withhold medical supplies. However, the collapse of the image of the US in the eyes of many Europeans may be more shocking. Over 70 per cent of Danes and Portuguese say that their perceptions have worsened, while 68 per cent of French people, 65 per cent of Germans, and 64 per cent of Spaniards say the same thing. This is not, in our view, simply one more indication of how strongly Europeans oppose Trump’s way of doing foreign policy. The covid-19 crisis has revealed a US divided in its response to the present crisis and haunted by its history. If Trump’s America struggles so much to help itself, how can it be expected to help anyone else? If this domestic chaos continues, many Europeans could come to see the US as a broken hegemon that cannot be entrusted with the defence of the Western world.

While the pandemic has not yet changed Europeans’ domestic political preferences, ECFR’s new data show that it has dramatically changed how they see the world beyond Europe. Covid-19 follows the global financial crisis, the refugee crisis, and the climate emergency. These big global events that change how Europeans see the world are, in turn, leading citizens to radically reassess the purpose and role of the EU in their lives. If we look more deeply into the data, we are able to construct three mental models that European citizens use to understand the world after the crisis.

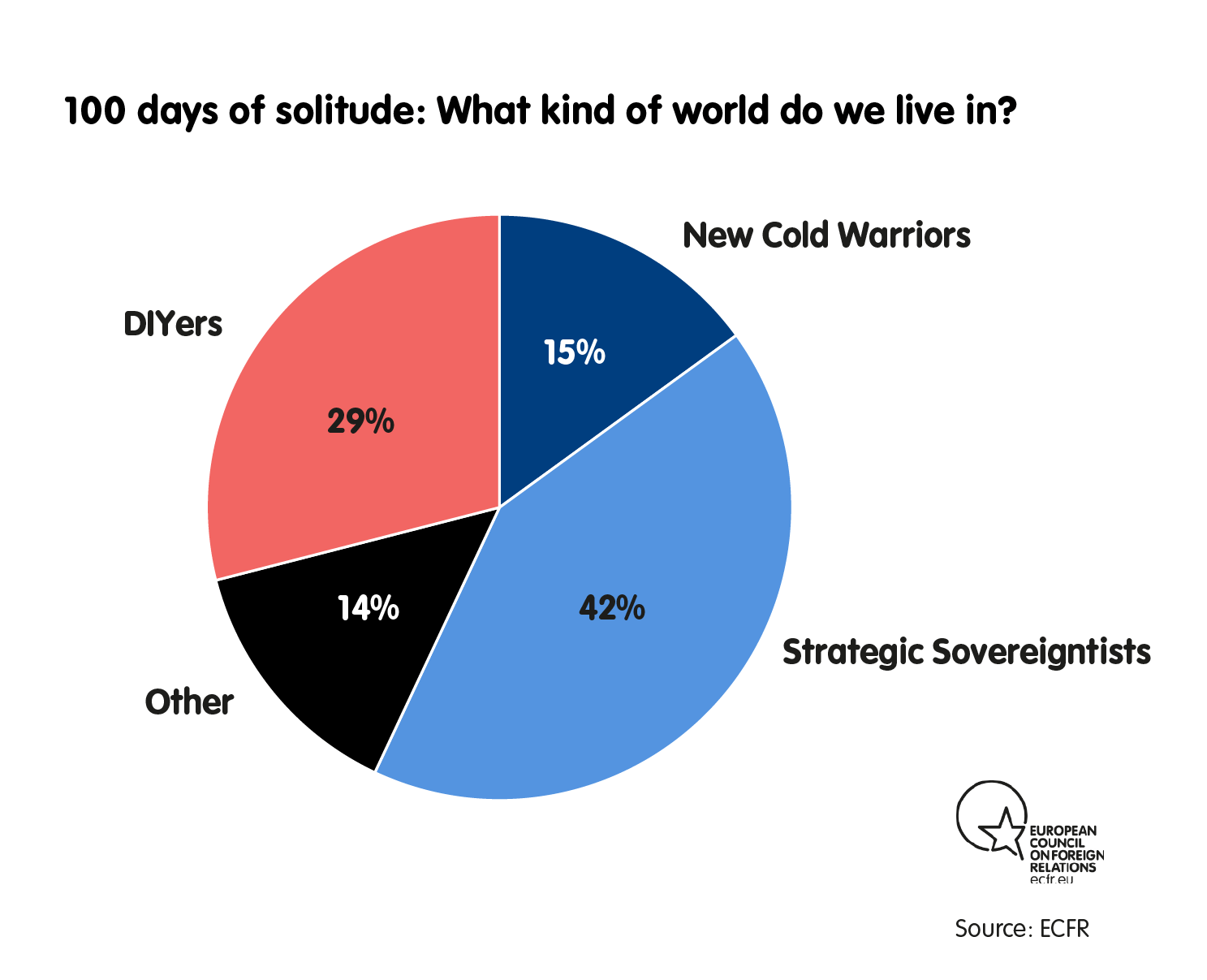

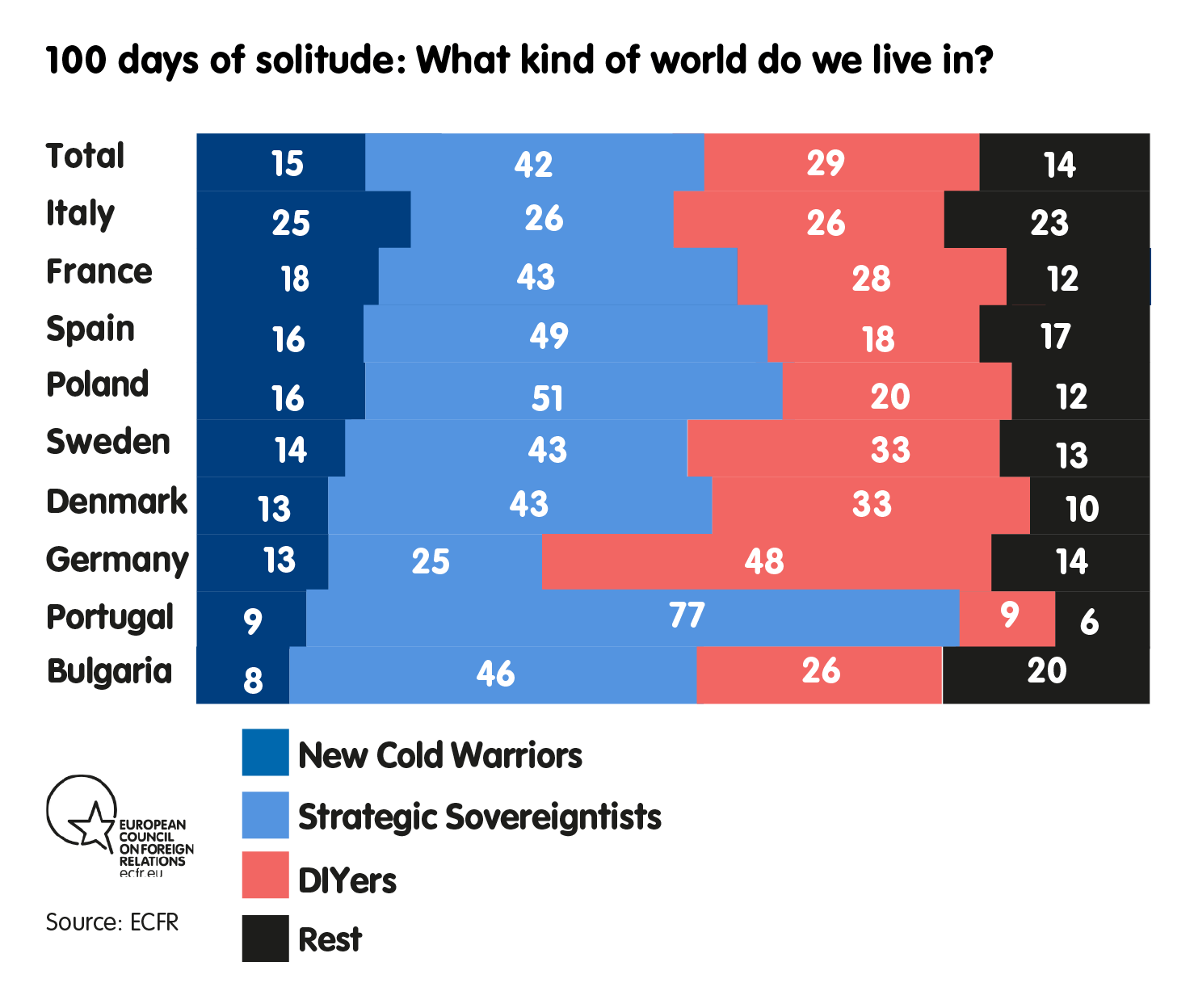

Firstly, we have “DIYers” (Do-It-Yourself), who think that, after the crisis, geopolitics will be like that of the nineteenth century, when every nation was on its own. They make up 29 per cent of those surveyed. Some have confidence in their state’s capacity to make alliances of convenience with other players to defend its interests. Others do not have faith in their state, but they see no prospects for effective cooperation on either the European or global level.

Secondly, we have the “New Cold Warriors”, who make up 15 per cent of those surveyed. People with this kind of world view think that geopolitics will resemble that of the twentieth century. They believe the future is a bipolar, with the US as the leader of the free world and China the leader of an autocratic axis that includes states such as Russia and Iran.

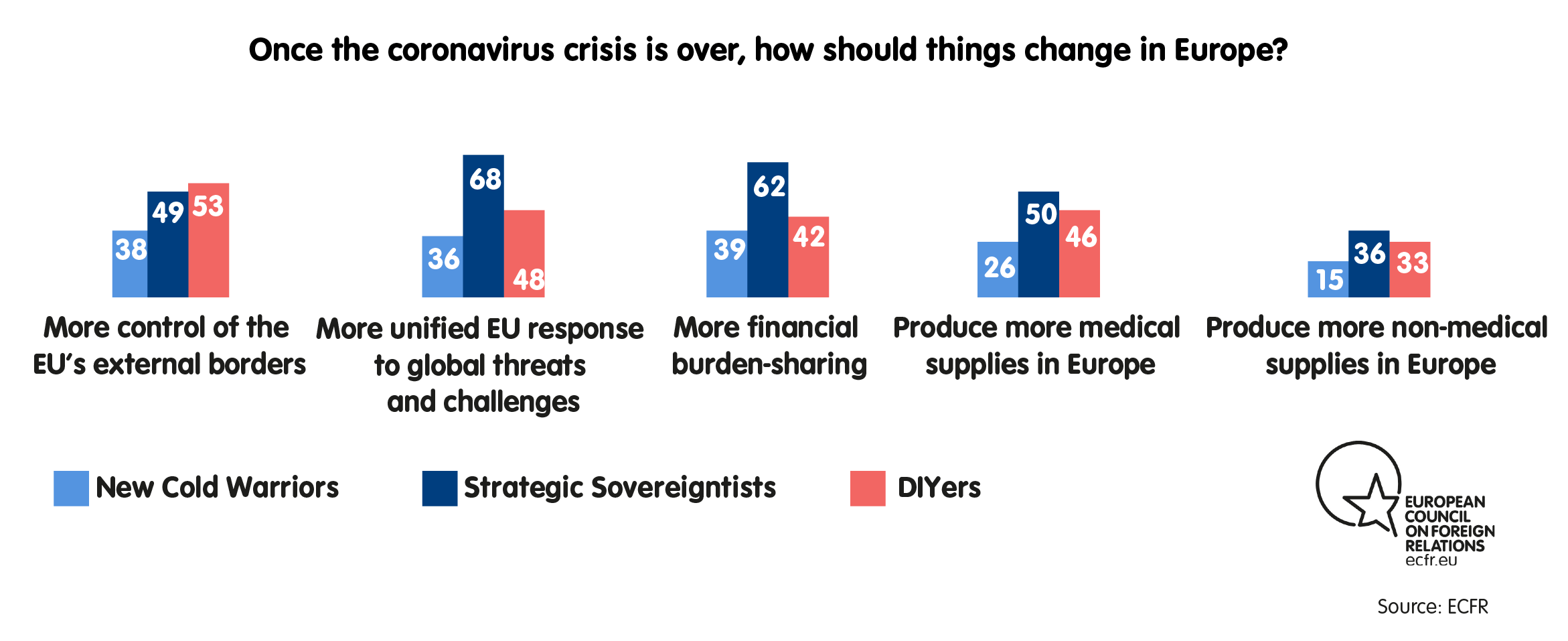

Finally, the biggest and politically most important group are the “Strategic Sovereigntists”, who make up 42 per cent of those surveyed. These citizens tend to believe that the twenty-first century will be a world of blocs and regions. In their view, Europe’s relevance in this new era will depend on the EU’s capacity to act together. This world view scrambles the traditional dividing line between globalists and nationalists. On the one hand, nationalists are starting to realise that their states can only be sovereign as part of a European bloc. On the other hand, disappointed globalists have come to realise that their dream of a multilateral world of global governance cannot be fulfilled with Trump, Xi, and Vladimir Putin in power. It was not covid-19 but the failure of the international community to come up with effective common responses that transformed some of yesterday’s cosmopolitans into today’s new Strategic Sovereigntists. For them, Europe is no longer mainly a project motivated primarily by ideas and values; it is a community of fate that must stick together to take back control over its future.

This group’s emerging world view is best described as “progressive protectionism”. Because Europeans are less able to rely on global solutions to foster their vision of what kind of world they want to live in, they have decided to create their utopia on the European landmass. This has implications for how they view issues that are key to their future, such as environmentalism and the digital agenda. Our polling shows that Strategic Sovereigntists are the group whose support for action on climate change increased the most because of the pandemic. However, their route to advance this agenda does not lie in preaching to others but compelling them to follow European values by implementing carbon and digital taxes.

Every country contains representatives of each of the three groups. But the way the groups are distributed challenges both countries’ self-perceptions and their stereotypes about others. For example, Germany prides itself on its commitment to Europe but contains far more DIYers than any other surveyed country. Many people have characterised eastern Europeans as New Cold Warriors, given their fierce Atlanticism, but our poll shows that it is actually the Italians and the French who are most likely to be New Cold Warriors. The strongest believers in Europe strengthening its own sovereign ability to act in a regionalist world are not the French, but the Poles, Portuguese, and Spaniards. The survey has also uncovered important domestic political divisions: in France, for example, 69 per cent of citizens who voted for Macron believe in a regionalist world, while almost half of Marine Le Pen’s supporters are DIYers. In Germany, Social Democrat and Green supporters are more likely than the German average to be Strategic Sovereigntists.

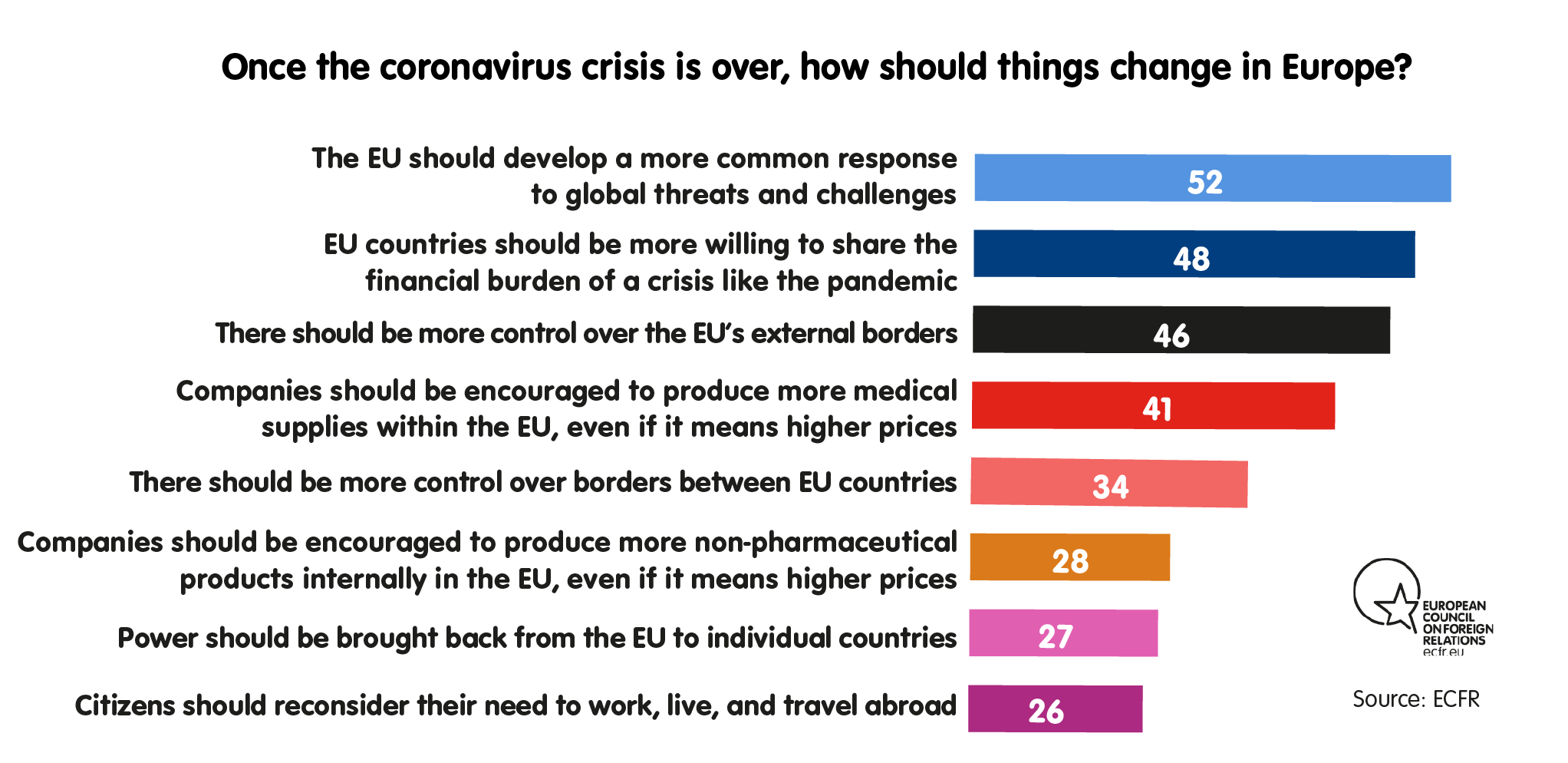

Those who believe in a regionalist world foresee that the winners or losers of the covid-19 crisis will be not individual nation states or particular political systems, but regions and blocs that are able – or unable – to wield power on the world stage. Europe’s best chance to avoid becoming beholden to other blocs is, therefore, regional consolidation and the creation of a more unified and powerful EU. While European leaders have not given up on effective multilateralism – the Coronavirus Global Response Pledging Conference is the best example of this – almost half of Europeans see economic and political consolidation within Europe as the best insurance policy in the face of deglobalisation. This attitude is discernible when Europeans are asked whether they believe in greater cooperation: their answers show that those who believe that the future is regional are more likely than others to say that the EU must be more unified and that the financial burden of the crisis should be shared. They are also more likely to believe that both medical and non-medical supplies should be produced in the EU.

When it comes to whether manufacturing might move from China to Europe, the greatest support for such a shift comes from the EU’s biggest countries – France and Germany. Citizens in smaller countries appear to consider protectionism less viable. Ideas of protectionism are also important when it comes to the green and digital agendas: fearing a world of zero-sum competition and economic protectionism, many Europeans are looking to a form of progressive protectionism in which Europe places high taxes on goods whose production harms the environment. By doing so, Strategic Sovereigntists believe that they can promote their values and preferences even in an unfriendly world.

Conclusion: Are we in a Hamilton moment?

European governments and the institutions in Brussels have realised that the coronavirus crisis has created an opening for collective European action. The Franco-German recovery plan presented in May could be the beginning of a vital new stage of the European story. But, for leaders to bring a more powerful and unified Europe into being, they must make the right policy choices and tailor their arguments in a way that connects with – rather than repels – European voters.

Commentators were quick to describe the Franco-German agreement as a ‘Hamilton moment’ for the EU, suggesting that the covid-19 response is a staging post on the road to a United States of Europe in which more sovereignty will rest with Brussels. This idea comes from Alexander Hamilton, the first US treasury secretary, who set his country on its inexorable path to federalisation through the mutualisation of debts from the revolutionary war. His central message was: ‘We died together, so we should pay together’. Mutualisation was the most powerful expression of the end of the autonomy of American states.

However, our polling suggests that European citizens’ feelings today are closer to those expressed by British historian Alan Milward than they are to the thrust of the Federalist Papers. Milward’s revisionist history, The European Rescue of the Nation-State, argued that the driving force for the European project was a recovery – rather than sublimation – of national sovereignty. But, whereas Milward’s narrative was about rescuing states in the 1950s from the destruction brought about by war between Europeans, the challenge to the state in 2020 comes from outside Europe. Europe needs to win its sovereignty back from China and from Trump’s America, as well as from digital giants such as Facebook and Huawei.

In this interpretation, EU action is imperative by simple virtue of the fact that we all live on the same continent and face the same external threats. China and the US manipulate crises such as pandemics or climate change, increasingly instrumentalising global institutions and even the globalised economy to compete with each other. Europeans can see that failing to act together means they risk becoming casualties in a Sino-American game of chicken.

In light of this, the European project should be rethought not as an integration process based on ideals, but as one based on fate. Shared geography dictates common action even more than shared values. In this context, what we are witnessing is more a ‘Milward moment’ than a ‘Hamilton moment’; less a radical step towards federalisation, and more a burgeoning consensus on the need to use Brussels as a tool to empower the nation state.

But, even as Europeans recognise that they need each other so they can face a hostile world together, they lack confidence in both their own governments and European institutions to provide the protection they require. Worse, they continue to distrust the experts and technocrats who form the brains and backbone of the European institutions.

All of this implies that European leaders should not couch arguments about burden-sharing in terms of European solidarity or technocratic efficiency, but in terms of national interests. They should describe the single market as an opportunity to save domestic jobs at a time when trade with China and the US is set to become increasingly difficult. Such an approach to describing European action would help strengthen support for financial burden-sharing. Even fiscally conservative states would see that it is in their interest to, for example, contribute to saving companies in other EU member states.

For many years now, people have compared Euroscepticism and populism with a malady that has taken on epidemic proportions. Among European leaders such as Macron and Olaf Scholz, there is now a hope that a real virus may have helped cure the political virus of anti-Europeanism, and that populism is now in retreat. Our polling shows that the overwhelming majority of people want more EU cooperation; and that these voters are spread right across the continent – north, south, east, and west.

But it is important to understand the drivers of this new form of pro-Europeanism in order to ensure arguments land with voters. Those who seek to elevate Hamilton should be aware of how dismissive the public is of the existing EU institutions in Brussels. The roots of new demands for cooperation do not lie in an appetite for institution-building but rather in a deeper anxiety about losing control in a dangerous world. It is about strengthening rather than weakening national sovereignty. This is a Europe of necessity rather than of choice.

In such circumstances, if Europe’s political leaders deploy a federalist narrative to try to create a more powerful and unified Europe, it could destroy this very goal. A ham-fisted case for integration could fuel an outbreak of anti-EU sentiment even more virulent than the one before – and not just, or even especially, in the European periphery. This time, it could be at the very heart of Europe, in fiscally wary Germany. Just as with the Spanish flu, it is the second wave of Euroscepticism that could prove the most deadly.

Methodology

This paper is based on a public opinion poll in nine EU countries carried out for ECFR by YouGov (and, in the case of Bulgaria, by Alpha Research) in the last week of April 2020.

YouGov conducted the online survey in eight countries: Denmark (sample size 1,000), France (2,000), Germany (2,000), Italy (1,000), Poland (1,000), Portugal (1,000), Spain (1,000), and Sweden (1,000). YouGov used the Active Sampling method, which is explained in more detail here. The results from YouGov are politically and nationally representative samples.

Alpha Research conducted the survey in Bulgaria (sample size 1,000) using a mixed model of CAWI and CATI in order to reach the intended nationally representative sample. This is because the some socioeconomic groups in Bulgaria do not consistently have internet access. Both YouGov and Alpha weighted the results accordingly in order to optimise the results.

The exact dates of polling were: Bulgaria (23 April – 5 May), Denmark (23 April – 28 April); France (24 April – 28 April); Germany (24 April – 28 April); Italy (23 April – 28 April); Poland (24 April – 3 May); Portugal (27 April – 9 May); Spain (24 April – 4 May); Sweden (24 April – 29 April).

In this study, identification of different party electorates in individual countries is based on voter intention in the case of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden – and on past vote in the case of Bulgaria (2017), Denmark (2019), Poland (2019), and Portugal (2019).

The world views are constructed based on GNE12 (who will offer support during covid-19), GNE5 (perception of US, China, Russia), and GNE8 (attitudes towards EU needing a more unified response, and pushing businesses to produce medical and non-medical supplies in the EU). Those who say they cannot rely on anyone for support are in the DIY group; those who say they expect support from the EU or EU countries, or who believe that businesses should produce medical or non-medical goods in the EU and that the EU needs to be more unified, are in the Strategic Sovereigntists group; and those who say they can rely on the US, or have an improved image of the US, or a worse image of China, Russia, or Iran are in the New Cold Warrior group.

DIYers (Do-It-Yourself)

Convinced that we live in a world where all states are on their own, constituting 29 per cent of the EU electorate covered in the survey.

- Male/Female: Evenly balanced

- Median age: The oldest group of all, with a median age of 54

- Where found: Strongest in Germany (48 per cent) and least likely to be found in Portugal (9 per cent) and Spain (18 per cent)

- Voting behaviour: As likely as New Cold Warriors to vote for a Eurosceptic party (26 per cent)

New Cold Warriors

Believing in a bipolar world with the US as the leader of the free world and with China becoming the leader of an autocratic axis that includes states such as Russia and Iran, they constitute 15 per cent of the EU electorate covered in the survey.

- Male/Female: Majority female (54 per cent), but fairly representative of men and women

- Median age: The youngest group of all, with a median age of 43

- Where found: Greatest representation in Italy (25 per cent), and least representation in Bulgaria (8 per cent) and Portugal (9 per cent)

- Voting behaviour: In comparison to the other groups, least likely to vote for a pro-EU party (46 per cent) and most likely to abstain (8 per cent) or to be undecided (21 per cent); as likely as the DIYers to vote for a Eurosceptic party (26 per cent)

Strategic Sovereigntists

Believing in a world of blocs and regions, in which Europe’s relevance depends on EU’s capacity to act together, constituting 42 per cent of the EU electorate.

- Male/Female: Evenly balanced

- Median age: Median age of 50

- Where found: Greatest representation in Portugal (77 per cent), Spain (49 per cent), and Poland; least representation in Germany (25 per cent)

- Voting behaviour: Most likely to vote for a pro-EU party (65 per cent)

Acknowledgements

The authors of this report are hugely grateful to colleagues across the ECFR network for all of their input into the research and production of this report. In particular, we would like to thank Susanne Baumann and Susi Dennison for leading the Unlock project so brilliantly. We would like to thank Franziska Brantner, Ismaël Emelien, Lykke Friis, and Adam Lury, and Alex Soros for their deep insights, ideas, and advice. Vessela Tcherneva and Jeremy Shapiro oversaw the entire programme and research management with their customary brilliance, while Piotr Buras, Jana Puglierin, José Ignacio Torreblanca, Tara Varma, and Arturo Varvelli gave us vital advice and insights from their national capitals. Pawel Zerka and Philipp Dreyer were responsible for the data analysis and allowed us to learn many things from it. Lucie Haupenthal was the perfect partner throughout the writing process, helping steer our progress, trying to pin down our emerging insights in successive drafts, and being an amazing research assistant and intellectual sparring partner. Swantje Green and Andreas Bock provided inspiring and tireless work on Unlock that helped this project make an impact in the world. Adam Harrison has been an exemplary editor. We would also like to thank Paul Hilder and his team at Datapraxis for their patient collaboration with us in developing and analysing the dataset and to YouGov for conducting the fieldwork. Despite all these many and varied inputs, any errors in the report remain the authors’ own.

We would like to thank the Europe’s Futures project, a joint initiative of IWM and ERSTE Foundation, for their support of this publication.

About the authors

Ivan Krastev is chair of the Centre for Liberal Strategies, Sofia, and a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. He is co-author of The Light That Failed: A Reckoning, among many other publications.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is the author of Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century and What Does China Think?, and the editor of Connectivity Wars. He presents ECFR’s weekly World in 30 Minutes podcast.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.