Beyond Global Britain: A realistic foreign policy for the UK

Summary

- The UK government’s vision for Global Britain aims to restore British greatness as a maritime trading nation. But this vision does not reflect today’s geostrategic realities, including the continuing importance of the EU.

- The Johnson government seems to need the perennial fights of a permanent Brexit, but this approach is eroding the UK’s capacity to cooperate with the EU on foreign and security policy.

- At the same time, as ECFR polling reveals, the British public do not have any particular animus towards the EU. While the public value British sovereignty and independence, they would support a foreign policy that worked cooperatively with the bloc.

- The public is on to something: Britain still has extraordinary assets and can forge an effective foreign policy. Yet, to do so, it must focus on British strengths, avoid military adventures in distant lands, and find balanced, effective working relationships with the EU and the US.

- British security and prosperity will increasingly depend on unromantic issues such as carbon tariffs and investment screening – on which the best way to protect British interests is to triangulate between the EU and US positions.

Introduction

On 3 February 2020, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, fresh from the triumphant conclusion of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union and a crushing general election victory, chose the historic setting of the Old Royal Naval College at Greenwich to set out his vision of the country’s new role in the world. New, but also old: Johnson exulted in the Painted Hall’s baroque celebration of the United Kingdom’s past maritime greatness, as he coloured the glorious future awaiting Britain as a global champion of free trade.

Johnson’s vision for Global Britain had little role in it for the EU. Having executed at long last the geopolitical miracle of Brexit and unwound the UK from the thick tangle of its EU obligations, it only made sense for the UK to stride out into the world in a similarly independent fashion. For political observers in Britain and beyond, Johnson’s determination to secure a fully independent foreign policy for the UK was part and parcel of his successful domestic political strategy of permanent Brexit. Even after formal Brexit, his government seems to need perennial fights with the EU to justify its political existence. For the Johnson government, Brexit has become more an ideology than a policy.

But the ideology of permanent Brexit cannot suspend the laws of distance and strategy. The UK may have left the EU, but it cannot leave Europe. From the geographical point of view, it seems clear that the EU remains Britain’s essential partner. In a world of increasing geopolitical competition, authoritarian advances, and geo-economic coercion, a medium-sized democratic country off the western coast of Eurasia can only hope to promote its interests in combination with like-minded liberal partners. With the United States ever more self-absorbed and focused on the Indo-Pacific and China, the EU is the UK’s necessary geopolitical partner.

Brexit Britain has many assets to bring to this partnership. Unlike in its “special relationship” with the US, it need not take the role of junior partner and follow its leader into whatever foolish adventure US domestic politics should prescribe. But it does need to move beyond the current squabbles over food and fish, to cut out the reckless juggling with Northern Ireland’s fragile peace, and to seek to form a working relationship that reflects Britain’s geopolitical vulnerability.

There is a way to accomplish this geostrategic alignment without sacrificing any gains in sovereignty Brexit may have brought. The current British government does not seem to want to take such an approach. But it remains a very viable political strategy in Britain. As a recent poll conducted by the European Council on Foreign Relations shows, the British public as a whole are, at best, indifferent to the restoration of Britain as a global military power and, in the wake of Brexit, have no particular animus towards the EU.

Accordingly, this paper offers a justification and a blueprint for how an independent Britain could profit from its unique assets, its geographic position, and – most importantly – a close strategic partnership with the EU to both protect its sovereignty in a world of heightened geopolitical competition and become a force in global affairs. As is also reflected in ECFR’s poll, such a policy can command political support in the UK, despite the daily drumbeat of EU-bashing by the Johnson government.

Global Britain is a delusion rooted in a misremembered imperial past. But the UK need not shut itself off from the world or accept a permanent position of subordination in global affairs. The UK, working with the EU, has the capacity and the political will to find a better path – but only if its leaders have the wisdom to seize the opportunity.

Global Britain on the slipway

Johnson seems broadly unconcerned with the UK’s stark geopolitical vulnerability. Remainers harped on about the economic damage of Brexit during the referendum campaign – and it did them little good. The Leave campaign successfully dismissed such talk as “Project Fear”, urging all patriotic Britons to draw inspiration from their buccaneering forebears of the first Elizabethan age, who had set Britain on the path to unmatched greatness. Britain’s new global strategy must similarly ignore what Johnson calls the “doomsters and gloomsters” who forever predicted British failure. The notion of Global Britain was imprecise but evoked a world of opportunity awaiting a nation “unshackled from the corpse that is the EU” – as one campaigner put it – and set forth to new horizons.

All countries are prisoners of their past; and the Leave narrative successfully tapped into an enduring British sense of former greatness, exemplified by the country’s continuing preoccupation with the second world war. So, it is unsurprising that Leave voters tended to be relatively old, often drawn from a generation who had learned on their parents’ knees how the true character of the British people had been revealed in 1940. That heroic moment, when Britain “stood alone”, was all the more poignant for being a decisive juncture in the country’s decline from empire: the sequel to victory would be long years of privation and economic crisis, and a humiliating late entry into the new European Community. ‘Make Britain Great Again’ might have been the Brexiteers’ slogan, if an earlier variant of this virus was not already in circulation in America.

Shortly after the Greenwich speech, Johnson announced that his government would publish the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development, and Foreign Policy – which Downing Street described as “the largest review of the UK’s foreign, defence, security and development policy since the end of the Cold War”. ‘Global Britain’ was a title in search of a plot, which it was now time to back-fill. The review was published on 16 March 2021 as ‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age’. The government had not, however, waited for the review’s conclusion to announce its most significant outcomes: a “tilt to the Indo-Pacific” (home to the planet’s most dynamic new economies, set to overtake the moribund EU); a £4 billion-a-year cut to the foreign aid budget, and subordination of the Department for International Development to the Foreign Office in a new Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office; and a £16.5 billion boost to the defence budget over the next four years. The major beneficiary was to be the Royal Navy – which, Johnson assured parliament, would regain its status as the foremost naval power in Europe.

A deep cut to foreign aid, though an evergreen hit with the British public and no doubt influenced by the country’s difficult fiscal position, would prove unexpectedly controversial. Otherwise, however, these down-payments on the Integrated Review sat happily with the Brexiteers’ vision of the restoration of Britain’s proper role as a global maritime and commercial power. ‘Britannia rule the waves’, the promise of the much-beloved anthem of the British Empire, might be stretching it a bit after the retreats of the twentieth century. But a national renaissance certainly seemed possible.

Global Britain’s first report card

Two years on from this glad, confident morning, how is it all going? Splendidly, in the government’s telling. A carefully staged G7 summit in Cornwall in June 2021 showcased Britain’s restored international leadership. It was also the occasion to announce an agreement on a new free trade deal with Australia – only the latest in more than 60 such deals already struck by post-Brexit Britain across the globe. And the maiden deployment of Britain’s massive new aircraft carrier to the Far East was a potent symbol of the country’s revived military might and global presence.

The reality is less encouraging. Almost all the “new” free trade agreements are simply rollovers of the EU deals that Britain had benefited from as an EU member. True, there is no EU-Australia deal yet (though one is imminent). But Britain’s Australia deal is small beer, estimated by the House of Commons Library to add only between 0.01 per cent and 0.02 per cent to GDP. And Australia’s hard-nosed negotiators took advantage of Britain’s evident neediness to secure an outcome that was weighted 6:1 in their own favour and devoid of the climate change conditions that the UK aimed to include.

Possibly more promising is the start of negotiations for Britain to join the 11-nation Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – formerly known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership. This grouping includes many of those dynamic Indo-Pacific economies that Brexiteers see as their El Dorado. Yet the additional gains from CPTPP membership are unlikely to be substantial, given that Britain already has bilateral free trade agreements with the four most significant economies in the partnership (Japan, South Korea, Canada, and Singapore) – again, legacies from EU membership. The government’s own figures estimate the potential boost to GDP at less than a tenth of one per cent.

To put this in context, the government’s economic forecaster puts the damage to GDP from Brexit at 4 per cent, or twice that of the pandemic. Total UK-EU goods trade was down by 15 per cent, or £17bn, in the second quarter of 2021 compared to the same period in 2018 (which the organisation used as a comparator). Although it is not easy to distinguish between the effects of Brexit and the pandemic, one estimate puts the reduction in the UK’s overall goods trade due to Brexit at 11 per cent. An academic analysis of the government’s figures concludes that, overall, new trade deals “barely scratch the surface of the UK’s challenge to make up the GDP lost by leaving the EU”.

Indeed, a combination of the pandemic and Brexit have left the government with a severe fiscal headache. In the fiscal year to March 2021, the public sector borrowed £298 billion, more than 14 per cent of GDP – a higher proportion than at any time since the end of the second world war. In late June 2021, the net debt of the public sector stood at £2.2 trillion, almost exactly 100 per cent of GDP (a level not seen since 1961, when Britain was still paying down its mountain of war debt). With the National Health Service now facing a backlog of almost 6 million cases unrelated to covid-19, and the social care system close to collapse, the government has introduced a new health and social care levy that will take the UK tax burden to its highest level since the 1950s.

With this tax hike, the government’s official forecaster projects a reduction in the debt to 88 per cent of GDP in the coming five years. But the situation remains extremely fragile: supply chain problems and labour shortages (both exacerbated by Brexit), along with rising energy prices, are contributing to the development of a cost-of-living crisis. The Bank of England expects inflation to hit 5 per cent next year. Nor is it clear how the government intends to fund its climate change commitments or pay for Johnson’s signature promise to “level up” those deprived regions of the country that delivered him his 2019 election victory.

It should come as no surprise that the UK’s new trade deals seem to offer such meagre compensation for its lost trade with Europe. Geography still matters. Technology has provided global communications systems and logistics supply chains that operate with unprecedented speed and reliability. But it has not abolished distance, as the widely accepted gravity model of trade flows confirms. It is still much easier to trade with neighbours than in markets on the far side of the world.

But what of the two biggest economies of the Indo-Pacific, China and India? These two countries, along with the US, were invoked by Brexiteers as huge markets that the EU had failed to access – places where buccaneering Britain could fill its boots. Johnson celebrated in May 2021 an agreement to open trade talks with India. Annoyingly, EU leaders reached exactly the same stage four days later. And, given the many false dawns of past decades, trade experts counsel against anyone pinning much hope on a deal to open up the most protectionist major economy in the world.

Not even the most Panglossian Brexiteer now foresees any prospect of a trade deal with China – or even advocates one, given the rising bilateral tensions over Huawei, Hong Kong, and China’s treatment of the Uighurs. The Integrated Review pulls few punches about the geostrategic challenge that China increasingly presents to all Western countries, while acknowledging that the country continues to be of huge economic importance to the UK. Sensibly, it concludes that: “we will continue to pursue a positive economic relationship, including deeper trade links and more Chinese investment in the UK. At the same time … we will not hesitate to stand up for our values and our interests where they are threatened”. But the document reveals little about how the government hopes to manage this difficult balancing act.

One certainty, however, is that the UK’s deployment of a carrier strike group in the Pacific has only made the situation more difficult. The dispatch of a naval armada to adjacent seas was inevitably seen in Beijing as a provocation, and an act of alignment with the US strategy of military containment. To make matters worse, though the great flagship was ready for its maiden deployment (some years late), this was not the case for the F-35 aircraft it was supposed to carry. Only eight were available to equip a carrier with the capacity for 40. Ten US Marine Corps aircraft had to be embarked to make up the numbers. A US escort destroyer underlined the perception of a UK-US operational partnership – a perception that Johnson was, for other audiences, happy to emphasise. The strike force in the event wisely chose to skirt around the edges of the South China Sea, avoiding the specifically contested waters. Yet when a detached escort transited the Taiwan Strait on its return route, China accused Britain of “harbouring evil intentions”.

If the government hoped that this naval excursion to the Indo-Pacific might at least gratify the Americans, and perhaps even revive prospects for a US-UK free trade agreement, there was further disappointment in store on both counts. In an unguarded moment, US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin made clear his view that the British (and, one may assume, other Europeans too) would make a better contribution to Western security by focusing on their own neighbourhood rather than dipping their toes in Far Eastern waters. As for any trade deal, Secretary of State Antony Blinken had already explained that the new administration was simply not interested – partly for domestic reasons, but also due to frustration with Johnson’s willingness to renege on the Northern Ireland Protocol in his EU withdrawal agreement. Johnson’s first visit to the White House in September produced only President Joe Biden’s reaffirmation that a bilateral trade deal was off the table.

Less than a year after the completion of Britain’s departure from the EU, the Brexiteer prospectus of a prosperous trading future awaiting Britain in the wider world looks like a pipe dream – and government claims to the contrary like so much whistling in the dark.

Biden’s rebuff on trade was humiliating for Johnson – albeit not as humiliating as the precipitate US withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021. Of course, all NATO allies were similarly snubbed. But only Britain had just published a government document (the defence supplement to the Integrated Review) congratulating itself that “the UK and the US are indispensable allies and pre-eminent partners for security, defence and foreign policy. UK-US defence cooperation is the broadest, deepest and most advanced of any two countries in the world.” And it was Johnson who set up the G7 video conference at which Biden flatly refused to delay the withdrawal by even a few days. Little wonder that, when a shocked House of Commons returned from its holidays to debate the Afghan fiasco on 18 August, former prime minister Theresa May demanded to know: “where is Global Britain on the streets of Kabul?”

Happily for Johnson, the serial embarrassments that had marked the first year of liberated Britain’s return to the world stage were about to be punctuated by an unexpected coup – the surprise new defence partnership with the US and Australia, AUKUS.

This unexpected pact will apparently involve the provision of nuclear-powered submarines and a range of other armaments to Australia, along with cooperation in key security fields such as cyber, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing. What more dramatic proof could there be of Britain’s return to the Indo-Pacific as a major player? And what a boost for the UK defence industry! The fact that the French were incensed by the loss of a submarine contract they thought was theirs only added to the sweetness of the moment.

Britain could also draw satisfaction from its implied restoration in American eyes to the status of a valued military ally. A recent ECFR survey (see below) shows that the British public has fallen out of love with the famous “special relationship”, but the British military and defence establishment still yearn for the approbation and respect of their American big brothers. Their enthusiasm for playing the loyal first lieutenant, whether in NATO or the Middle East, has evidently not been dimmed by the Iraq and Afghanistan misadventures; so, they have been relieved that, after a fractious few months, they once again feel included: a whole new vista of strategic partnership with the mighty US appeared to have opened up before them.

Only when the initial sugar rush subsided did doubts surface. How much of the work would the American arms giants be ready to allow British companies to pick up? The missile orders specified so far are all for US armaments. The same will surely be true of the submarines themselves, not least in view of the procurement disaster that Britain’s Astute-class hunter-killer submarine programme has become. Indeed, what is Britain actually doing in this arrangement? The only plausible explanation seems to lie in the US Navy’s visceral reluctance to share its nuclear propulsion technology with any ally, no matter how close. They had done so once only, in 1958, when forced to help the British get into the game. In the 60 years since then, American and British nuclear power plants have inevitably evolved in significantly different ways: so, the Americans may actively prefer the British to supply the nuclear propulsion units to Australia for inclusion in American boats, to protect their own – doubtlessly more advanced – technology. A useful windfall for British industry, but scarcely a bonanza.

AUKUS raises wider strategic questions as well. Arms partnerships on this scale will inevitably be interpreted as an implied security guarantee – and the US and Australia, each in open confrontation with the Chinese, will be happy for it to be seen as such. Yet Britain, as the Integrated Review makes clear, has no more real enthusiasm than other Europeans for volunteering for a new American-led cold war with China. Quite apart from the economic damage that would entail – what possible difference could a few visiting warships make to a superpower confrontation on the far side of the globe? The logic that led the British and other Europeans to take a pass on the Vietnam war continues to apply.

Besides, there is little evident enthusiasm on the part of others in the region to see old colonial powers now trying to reassert themselves and ratcheting up the tensions with China. Japan and South Korea, US treaty allies, have welcomed the AUKUS announcement. Others, such as India and Indonesia, have been notably more restrained. Members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations have a long tradition of seeking to maintain stability in the region through commercial relations and diplomacy rather than military confrontation or alliances with outside powers.

For these questionable benefits, the UK deeply damaged its security relationship with France, confirmed in the Lancaster House treaties of 2010 as its closest and most important military ally in Europe. A British return “east of Suez” may be emotionally satisfying for some Brexiteers, but it will not rejuvenate Britain’s international standing nor provide any meaningful compensation for the economic damage of Brexit.

Britain’s unsustainable longing to rule the waves

The big winner from Johnson’s £16.5 billion boost to the defence budget is the Royal Navy. As he enthused to parliament, “if there is one policy which strengthens the UK in every possible sense, it is building more ships for the Royal Navy”. It is certainly a popular policy among nostalgics and shipyard constituencies, but Johnson’s popularity and the national interest are not the same thing. In economic and strategic terms, it is a profligate waste of money.

Economically, the problem is not just that the pressure on the public finances is so acute: it is also the shockingly wasteful record of Britain’s defence spending. In recent times, Britain’s armaments industry and Ministry of Defence have demonstrated an eye-watering ineptitude in major procurements – as evidenced by the massive time and cost overruns involved in the acquisition of the Astute-class nuclear-powered submarines, the Type 45 air defence frigates, and the new aircraft carriers themselves. And the ministry has lost control of its finances. According to the most recent annual report by the National Audit Office on the affordability of the ministry’s procurement programmes: “for the fourth successive year, the Equipment Plan remains unaffordable … The Department faces the fundamental problem that its ambition has far exceeded available resources.” The report was published before Johnson announced the boost in spending. But Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee has since assessed that the extant “black hole” in the Ministry of Defence’s finances could be more than £17 billion – big enough to swallow the new £16.5 billion increment in its entirety.

Nor is it obvious where the Royal Navy can find all the extra manpower it requires. Even before Brexit, the armed forces were chronically understrength. Like the rest of Europe, the UK will face falling fertility rates and a growing shortage of young people in the years ahead. Short of a return to the Nelsonian tradition of the press gang, it is anyone’s guess how to crew a projected fleet of 24 destroyers and frigates in the 2030s.

Britain’s defence aerospace sector, a key economic asset, might seem a more promising bet. But a great deal rides on the Tempest project for a next-generation combat aircraft, and whether it can compete with a better-funded and more advanced effort conducted by France, Germany, and Spain. And picking fights with France can only damage the successful bilateral collaboration in the missile sector.

Even more fundamentally: recognising that China’s rise is indeed a geostrategic “challenge” that all Western countries need to take seriously, does it follow that doubling down on traditional military force is the smartest precaution to take? In an age when the spectre of nuclear war has long set limits on conflicts between major powers, and when the real struggle for hegemony increasingly seems to take place in arenas such as cyberspace and global supply chains, there is something fatally outmoded about a British foreign and security policy skewed towards heavy metal and high explosive.

Power and influence in today’s world

The Integrated Review is not blind to these new realities. It identifies an increasingly contested world, in which “the nature and distribution of global power is changing”, and states have diversified and enhanced their approaches to rivalry with one another. As the review puts it: “adversaries and competitors are already acting in a more integrated way – fusing military and civilian technology and increasingly blurring the boundaries between war and peace, prosperity and security, trade and development, and domestic and foreign policy”.

Globalisation and technological revolutions have driven these changes since the end of the cold war. A vast web of human and economic networks now stretches across the world, creating vulnerabilities and dependencies that are often unappreciated until things go wrong. The crash of 2008 exposed a global financial system that had escaped any one state’s control – or even understanding – while the pandemic has revealed not just the fragility of historical measures of disease control by quarantine, but also the vulnerability of international supply chains that were developed to meet the demands of economic efficiency without regard to security.

These vulnerabilities are evident when a fire in a California server farm takes down major British websites or a container ship stuck in the Suez Canal reveals that ‘just in time’ delivery systems are only an hour or two away from being ‘just too late’. A recent spate of ransomware attacks has highlighted the way in which so much critical national infrastructure depends on information technology systems, and is vulnerable to malign actors.

Such actors include governments as well as criminal groups. States are weaponising interdependence and taking advantage of asymmetric dependencies to achieve geopolitical outcomes: China uses its centrality in trade to isolate Taiwan, Russia spreads disinformation through the internet to divide Western societies, and even the US takes advantage of its core position in international finance to enforce its geopolitical preferences through sanctions.

Such malignancy was not much in people’s minds as the West emerged triumphant from the cold war, and this brave new chapter in human history opened. Globalisation was to be not just economically beneficial for the whole of humankind but would also hasten the universal triumph of liberal democracy.

With a faith reminiscent of the nineteenth-century liberals who saw empire in terms of a “civilising mission”, the EU framed a neighbourhood policy on the assumption that the states of north Africa and eastern Europe wanted to be not just richer but more like them. Looking across the Pacific, Americans expected a rising Chinese middle class (abetted by the role of an all-pervasive internet in supplying facts and truth) to weaken the grip of the Communist Party. The rules-based international order – organised to suit Western interests and values, under US hegemony – would draw in up-and-coming countries as they saw the light.

When did the dream die? With 9/11, and in the sands of the Middle East? With Russian President Vladimir Putin’s conversion of Russia into a mafia state? With the economic disillusionment of the 2008 financial crash? With the failure of the Arab uprisings? With the erection of the Great Firewall of China? With the election of Donald Trump as US president? Regardless, in 2021, there is no longer room for illusion: we have entered a new “Age of Unpeace”, as Mark Leonard calls it.

China and Russia are not looking to take their place at the West’s table – nor should one expect that of India, or of any other state that develops the capacity to compete technologically with the West. Rather, they will seek to use any leverage they can gain from the interdependencies of globalisation; to develop alternatives to the Western-dominated institutions of the established order; and to turn Western countries’ prized assets against them by infiltrating their systems (through hacking, intervention in their domestic political debates, or dark money flows). China will not be the only rising power to present itself to aspirant autocrats everywhere as the wave of the future, with democracy fated to succumb to the surveillance state.

Therefore, Britain is heading into turbulent global waters in the wrong kind of ship and with no reliable forecast to hand. The key uncertainties are whether American hegemony will endure in the face of China’s rise – and, for everyone else, how to triangulate between these rival titans. But there are plenty of subordinate dilemmas, too: how to learn from the successes of China’s model of state capitalism; how to mitigate vulnerabilities while maintaining a generally open economy; how to balance democratic freedoms with the new demands of internal security; and, while accepting the reality of ever more varied and pervasive state competition, how to foster global cooperation where problems such as climate change and pandemics admit no other solution.

All this underlines the need to recalibrate the metrics of state power. The full panoply of military power may be necessary to deter Russia from an overt (as opposed to hybrid) war in Europe, or China from invading Taiwan. But, elsewhere, America’s possession of unrivalled military might has arguably tempted the country into a series of damaging adventures. In modern times, military might is still a necessary deterrent against all-out warfare, but it is no substitute for the newer and more precise forms of power that states use under that shield.

No wonder that, from Iran to North Korea to Belarus, economic sanctions have become the preferred tool of Western coercion – though, in this environment, it is unclear how long the US will retain its stranglehold on global financial flows. Meanwhile, increasingly serious cyber-attacks have prompted Biden to warn that such operations could result in shooting wars (even as Western powers develop their offensive cyber-capabilities).

The decreasing salience of military power may explain why the Johnson government has offered no strategic rationale for expanding the navy (or, for that matter, increasing its stockpile of nuclear warheads) beyond the Indo-Pacific mirage and vague references to projecting power and protecting shipping lanes. The national memory, it seems, can be relied upon to recall the indispensable role played by the Royal Navy in the defeats of Napoleon, the Kaiser, and Hitler.

In Britain’s position at the western extremity of the Eurasian landmass, the threats that should keep its rulers awake at night are not primarily those of armed attack. They should be fretting about Russian subversion, Chinese economic and technological ascendency, and climate-induced mass migration. Fortunately, they have like-minded potential partners close at hand whom they can work with, if they choose to – and a range of assets more useful than aircraft carriers they can draw on, if only they accord them the right priority.

Britain’s more relevant assets, and their neglect

Again, the Integrated Review is alive to this. It identifies several key assets that should help the country survive and prosper in the new strategic environment – its international networks, its soft power, and its advanced cyber-skills. The document also reaches some sensible conclusions about where Britain should be placing its bets: by investing heavily in its science and technology base, building on existing excellence in information technology and the life sciences; and by seeking to play a leading role in efforts to set future norms and standards in what it terms “the frontier spaces” – areas such as artificial intelligence and the exploitation of space, where technological advances break the limits of current global governance. Similarly, the analysis rightly emphasises the importance of resilience and the protection of critical national infrastructure.

The Integrated Review is not a modest document. Its authors draw particular satisfaction from Britain’s status as a “soft power superpower”, with the report citing “our model of democratic governance, legal systems and Common Law heritage, the Monarchy, our world-class education, science and research institutions and standards-setting bodies, creative and cultural industries, tourism sector, sports sector, large and diverse diaspora communities, and contribution to international development.” And the review describes the BBC as “the most trusted broadcaster worldwide” and celebrates the UK’s strengths in diplomacy and development – all of which, it asserts, will ensure that Global Britain will be a “force for good in the world”.

The report notes that “the UK’s soft power is rooted in who we are as a country: our values and way of life, and the vibrancy and diversity of our Union”. Indeed, as China’s ‘wolf warrior’ diplomats seem to have forgotten, international influence is seldom enhanced by a menacing profile. Yet so many of the Johnson government’s instincts and policies seem focused, almost with laser precision, on undermining the very soft power assets lauded in the Integrated Review.

Britain’s image as a reliable, law-abiding country has deteriorated as it has become clearer that Johnson signed the EU withdrawal treaty without intending to abide by some of its most crucial provisions. His unlawful attempt to shut down an uncooperative parliament in autumn 2019 did nothing to excite international admiration for Britain’s model of democratic governance. Nor has the country’s commitment to an open, rules-based international order been easy to see when, in essence, Brexit has involved quitting the world’s largest free trade and free movement bloc while lampooning it for its addiction to bureaucratic standards and regulation. This cavalier attitude towards international agreements may be becoming a feature of the British government’s approach to foreign policy, even beyond Brexit-related issues. For example, UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak pushed for the UK financial services industry to be exempt from a new global tax regime, only days after he had accepted it in principle at a G7 finance ministers meeting. Many in EU capitals worry that this type of action is part of an emerging pattern, one which will make it hard to trust the word of the British government.

And tolerance of standards and regulation has hardly been a hallmark of how the Johnson government has conducted itself domestically. With a commanding parliamentary majority, it has not concealed its hostility to any institution or authority that might constrain its ability to do what it wants – no matter that these may be the very things that, in the words of the Integrated Review, help to “build positive perceptions of the UK”. The government has conducted a campaign to control the BBC through intimidation and financial pressure, installing a Conservative Party donor as its chairman, and manoeuvring to appoint a notorious foe of public-service broadcasting as its regulator. Britain’s legal system may be internationally admired – and used – but the government is introducing legislation to curb the judiciary’s ability to act as a check on executive power. Plans are afoot to criminalise everything from whistleblowing to asylum seekers entering the UK by ‘illegal’ means, to public protests that cause a ‘nuisance’. And a new government unit is apparently tasked with frustrating the workings of freedom of information legislation, much to the dismay of organisations such as Reporters Without Borders.

The Trump playbook is in evidence, from the general contempt for conventional political norms (to which Britain’s unwritten constitution is especially vulnerable) to a campaign to maintain the spirit of Brexit partisanship by inciting a “war on woke”. It is not hard to detect a concerted effort to retain power by rigging the system. A taint of corruption now hangs over Westminster. But perhaps the most damaging, and certainly the most conspicuous, assault on the attributes of British soft power has been the decision to slash the overseas aid budget by £4 billion annually, amid a global pandemic and a climate change crisis. A revolt over this by an unexpectedly large phalanx of the government’s own MPs overshadowed the G7 summit in Cornwall – where discussions were further soured by a new row over the Northern Ireland Protocol. On the key agendas of global covid-19 vaccination and climate change, a summit presented as an advertisement for Global Britain and demonstration of the country’s restored international leadership was a damp squib. (Significantly, the one important outcome, on the taxation of multinationals, was a US-driven initiative.)

COP26 – the 26th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, held in late October and early November 2021 – was arguably a better example of what Britain can still offer on the global stage. Johnson’s own contribution was typically eleventh-hour – and marred by the requirement to assure the world’s press that “the UK is not remotely a corrupt country” as the latest sleaze scandal engulfed his government. But the conference’s modest outcome – the planet lives to fight another day – was a credit to its president, the previously anonymous Alok Sharma, and the British official machinery that supported his preparatory work and negotiation of the final agreement. So, no triumph of British leadership, but confirmation of an enduring capacity to contribute less flamboyantly to tackling global problems.

Britain is operating in a complex and confusing world, in which global influence will accrue to those best able to understand what is going on, devise appropriate policy responses, and build international support for them. Diplomacy has long been seen from abroad as a traditional British strength – and the Integrated Review duly lays claim to “diplomatic leadership in a changing world”. Yet, when it comes to the reality of spending decisions, Britain’s diplomatic service – rightly suspected of inadequate enthusiasm for Brexit – receives no favours from the government. Britain’s new global role might seem to require a hike in diplomatic resources to restore all those historical relationships too long neglected. But, while Britain’s network of defence advisers will increase by one-third, the diplomatic service has been left to manage with the personnel it has. This will be more difficult than it once was, given the need to do business bilaterally in the 27 capitals of EU member states – now that Britain has set its face against dealing with the EU collectively in Brussels.

Perpetual Brexit

The Brexit divorce was never likely to be a harmonious business. Yet Johnson seems determined to keep the row over the Northern Ireland Protocol going. For example, he greeted the EU’s readiness to find practical solutions to the real problems affecting goods trade across the Irish Sea with new demands about the role of the Court of Justice of the EU – even though he must know these are non-negotiable, because they strike at the heart of the union’s treasured single market. The strategy seems bizarre – until one recalls the government’s interest in keeping the fires of Brexit antagonism burning until the next election.

Johnson and his supporters have defined themselves in the public imagination as Brexit warriors, forever fighting to maintain precious British sovereignty in the face of the EU’s revanchist efforts to control the minutiae of British daily life. From a political standpoint, this is a battle they cannot afford to lose. But, less obviously, it is a battle they cannot afford to win either: without its raison d’être, this is simply another Conservative government led by a raffish toff with a growing reputation for broken promises.

The strategy of perpetual Brexit calls for the EU to be forever seen as either pettifogging and vindictive – or simply irrelevant. The Integrated Review manages to ignore the organisation almost entirely. The new foreign secretary, Liz Truss, similarly felt no need to refer to the elephant in the room in her first speech in the role. The government made an abortive effort to deny ambassadorial status to the EU’s representative in London. This strategy of delegitimisation through wilful blindness is consistent with Johnson’s conclusion of a Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU that lacked any provision for continued cooperation on defence and foreign policy.

Johnson’s predecessor, Theresa May, had proposed something very different: a foreign policy and security partnership between Britain and the EU “unprecedented in its breadth, taking in cooperation on diplomacy, defence and security, and development”. But in the eyes of the Europhobes who propelled Johnson to power, this would only confirm the EU in its view that post-Brexit Britain must remain in the union’s orbit. True sovereignty required a completely new cosmology: Global Britain must break free of the union’s gravitational field altogether, and reclaim its position as one of the brightest stars in the wider firmament.

As discussed, this world view seems fanciful and dangerous. It is delusional to believe that there are vast untapped commercial opportunities on the far side of the world that can compensate for the loss of the EU single market. And it is dangerous to turn a Nelsonian blind eye to what Britain could gain in global influence through cooperation with the EU.

A UK foreign policy for a geopolitical age

If the world view behind Global Britain is indeed a delusion, post-Brexit Britain needs a foreign policy that reflects its new status outside the EU. The first step is to understand what the country wants and needs from its foreign policy, and what foreign policy the British public might support.

To this end, the European Council on Foreign Relations commissioned Datapraxis to poll the British public on these issues. Unsurprisingly, the overall conclusion from the poll is that the public is not very interested in foreign policy and is fairly evenly divided on most of the difficult questions of the day. “Don’t know” is the dominant answer to most questions. Nearly half of respondents (46 per cent) expressed no view on the Integrated Review’s big push into the Indo-Pacific. This indifference provides a lot of space for political leadership to set foreign policy, as the Johnson government has amply demonstrated. Still, within that fairly permissive environment, a few public preferences and even requirements for British foreign policy shine through.

The first is that the British public have an overall desire for independence and sovereignty.The British decision to leave the EU has complex origins but, clearly, a big motivator was a desire to allow Britain to decide controversial issues for itself – as part of what Johnson proudly hailed as “recaptured sovereignty”. On this point, the government does seem to channel the spirit of an increasingly nationalistic age. A plurality of UK citizens views the countries most often mooted as the UK’s key interlocutors – including the US, France, Germany, and India – as “necessary partners” rather than allies that share its values. From the public’s point of view, the UK does not seem to have a special relationship with any country (with the sole exception of Australia: Anzacs, Bondi Beach, and cricket still count for more than the country’s more recent role as a leading climate-wrecker). An earlier ECFR survey found that EU citizens take a similarly instrumental view of international relationships.

Of course, regardless of what the public wants, absolute sovereignty has never been an option for the UK. Johnson’s vision of a Britain in splendid isolation recalls a mostly imaginary past. More to the point, it mischaracterises the importance of the EU in limiting that independence. Well beyond the strictures of EU membership, the UK has undertaken a whole web of international obligations, in part because British policymakers have seen a net advantage in constraining UK freedom as the price for constraining others. In this way, the UK has sought to shape the world around it to better suit its national interests – and, indeed, to remain the master of its own destiny. Even outside the EU, this web of obligations will constrain British independence. Britain remains happily signed up to the International Court of Justice and a range of other supranational tribunals, even if the Court of Justice of the EU has now become anathema. Any successful British foreign policy will clearly need to balance this core desire for independence and self-control with the reality that an interdependent world limits freedom of action.

The second conclusion is the public do not seem to share their government’s desire for permanent political conflict with the EU. The public reaction to Brexit has not been as nationalistic as the government might have expected. Overall, the public are evenly split on who is to blame for the current impasse between the UK and the EU (39 per cent blame the former; 38 per cent the latter). Unsurprisingly, one sees a partisan divide on this topic – 71 per cent of Conservative current supporters blame the EU, while 67 per cent of Labour voters and 70 per cent of Liberal Democrat voters blame the UK. But, in fact, this divide is strongest among people who pay a great deal of attention to politics; most other people either do not have a view or, as a group, are less partisan on the issue. What is perhaps more significant is that 39 per cent of the British public, a majority of those with an opinion, see the EU as a key partner in the future. Only 22 per cent of respondents have a similar view of the US.

The public’s lack of enthusiasm for the US seems to extend to following it into a conflict with China. 55 per cent of respondents believe that there is already a cold war between the US and China. Moreover, 45 per cent believe there is a need to “contain” China - but among them only 39 per cent believe the UK should be involved in this. 46 per cent – and a majority of those with an opinion on the matter – would prefer to stay neutral in the event of a war between the US and China. Once again, UK citizens have similar views to their EU counterparts.

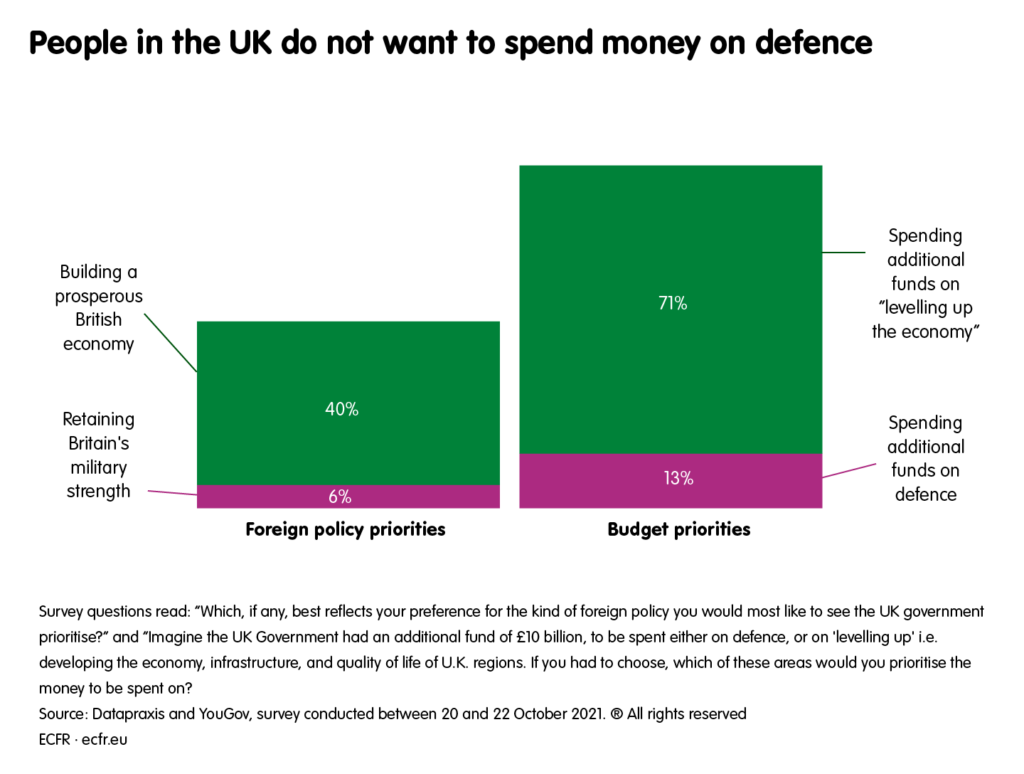

That preference for neutrality reflects a general desire to avoid military spending and military solutions to foreign policy problems. Only 6 per cent of respondents favour a foreign policy that prioritises Britain’s military strength. In contrast, 40 per cent want British foreign policy to focus on strengthening the domestic economy. Only 7 per cent would like to see a bigger British military presence in the Indo-Pacific, and only 13 per cent want more investment in the military at the expense of efforts to reduce regional inequality within the UK. The government’s pride in seeing British naval forces steam into the Pacific Ocean does not seem to inspire the public.

Of course, UK foreign policy should not only meet those demands but also protect key British interests that currently escape the public’s notice. To achieve this – and to avoid a public backlash – the government should:

- Preserve and modernise multilateral international and regional organisations. As a medium-sized power with a strong legacy position in various international organisations, particularly the UN Security Council, the UK has a strong interest in maintaining and reforming the system of international governance based around organisations such as the UN, the World Health Organization, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. The country should also incorporate new areas and standards into that system, including cyber-warfare and artificial intelligence.

- Promote free and fair trade. The UK has always prospered as a trading nation. But, to do so in the modern world, it needs to work within a system of free and fair trade that consists both of a web of trade agreements and a strong multilateral system centred around a reformed World Trade Organisation.

- Improve the resilience of supply chains.The pandemic has demonstrated the importance of ensuring that the UK has sufficient diversity of supply and domestic capacity to maintain resilient supply chains. Only then can it minimise the disruption caused by political crises or natural disasters.

- Protect the domestic political economy from malign influence.The weaponisation of interdependence has exposed the political and economic vulnerability of open societies to outside influence through mechanisms as diverse as disinformation, corruption, strategic investments, and general efforts to divide society. The UK government will need to guard its political economy against such threats through efforts such as investment control, anticorruption programmes, counter-disinformation operations, and the regulation of social media. It will need to be particularly attentive to foreign efforts to build on existing divisions within the UK to push for the break-up of the union.

- Mitigate the effects of climate change.Climate change is now a clear and present danger. For the UK government, this implies continued efforts to work with its international partners to minimise the changes in the climate to come, but also to adapt British society to those it cannot avoid.

- Promote European stability.British strategists have long understood that the defence of the UK begins by ensuring that the continent of Europe contains as many friendly powers as possible. Of course, this was part of the logic for joining the EU. But, even after Brexit, the UK has a clear interest in promoting stability and protecting democratic values in Europe, particularly against efforts by Russia to destabilise eastern Europe, including the Balkans and even EU member states.

- Strengthen science and technology partnerships.As the Integrated Review stressed, international collaboration with key partners, particularly the US and the EU, is essential to innovation and thus vital to the country’s future success. Brexit and the ensuing political disputes with the EU have threatened that cooperation. A lack of access to EU research would, in turn, make the UK a less valuable partner for the US. The defence sector is a particular concern here, given Washington’s long-standing refusal to share defence technology with anyone, and EU member states’ renewed efforts to boost their collaboration with one another while shutting Britain out.

- Adjust to the rise of China.Of course, the biggest foreign policy challenge in the next few years is likely to centre on how to react to and even influence China’s rise. For a distant UK, this challenge is less about military deterrence than resistance to economic or technological domination and the global retreat of democracy. China uses a variety of non-military “weapons” to extend its influence, including: investment diplomacy of the kind embodied in the Belt and Road Initiative; strategic industrial policy in key areas of technology, such as artificial intelligence; cooperation with other authoritarian states on surveillance technology; and the development of economic dependencies for geopolitical advantage.

Overall, this is a demanding set of requirements for a middle power in an age of geopolitical competition. Interestingly, though, it does not obviously call for some of the more difficult aspects of the government’s programme, particularly the military effort to help manage China’s rise in east Asia.

Even so, the magnitude of these tasks makes it clear that that the UK cannot achieve its goals alone. In almost every case, close working relationships with both the EU and the US will be necessary. But, in forming the alignments necessary to protect its interests, the UK risks creating a relationship of dependence. It is easy to resent the EU’s animal health requirements but hardly a gain in independence to trade them for a US requirement to accept chlorinated chicken. In other words, there are many threats to the British public’s demand for sovereignty and independence even outside the EU.

Cooperation is nonetheless compatible with the public demand for sovereignty and independence if the UK can maintain a diversity of partners and avoid excessive dependence on any one partner. In international affairs, monogamy is the enemy of sovereignty. Indeed, to the extent that the UK has had a “grand strategy” over the past half-century, it has been precisely to avoid having to choose between America and Europe. So, achieving a balance between the US and the EU is central to any effective UK strategy. The current British government may find it easier to work with Washington. Yet, on issues ranging from climate change to the rise of China, simple geography dictates that the UK’s interests and priorities will call for closer alignment with the EU than the US. To align too closely with either is to lose the ability to decide that Brexiteers claim to have fought so hard for.

In practice, this will mean that the UK will have to triangulate between the US and the EU on a host of issues. Triangulation does not mean serving as a bridge or a mediator. The US and the EU do not need or want British efforts to, in the words of then-prime minister Tony Blair, “build bridges of understanding between the US and Europe”. (The US and the EU have always managed to communicate with each other on their own – as shown by Biden’s meeting with European leaders in June 2021, which birthed a strikingly comprehensive US-EU to-do list.) Rather, triangulation means using various forms of influence with both partners to move them closer to the UK’s position. Climate change and technology regulation provide examples of how this might work across the broad spectrum of UK foreign policy challenges.

Climate change and carbon tariffs

The EU, the US, and the UK have distinct approaches to tackling climate change. The EU’s is broad, focused on control of high-emitting sectors, climate pricing, and efforts to export climate regulation to its trading partners. The US, by contrast, has focused on technological solutions, partly because it lacks the domestic consensus to impose a carbon price. The UK stands somewhere in the middle. Johnson recently endorsed a systemic approach to the UK’s net-zero emissions target, but his government has a tendency to launch various ‘moonshot’ approaches to the problem, inevitably including investment in space technology to address climate change and environmental management.

On climate issues, the EU’s carbon pricing system is the biggest point of contention between it and the US, and between the UK and the US, given that London wants to replicate this system. It is unclear whether or how the US would adopt a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) of the kind that the EU has proposed, and that has raised some eyebrows in Washington. US climate envoy John Kerry recently warned that the EU should use this levy only as a last resort, saying: “it does have serious implications for economies, and for relationships, and trade.” The US trade representative, Katherine Tai, has refused to rule out retaliatory tariffs if the EU implements the CBAM. The EU has backtracked slightly in response to US opposition, indicating that it could allow the country and other nations that lack a national carbon price to avoid tariffs if they implemented alternate regulatory measures.

From a UK perspective, this potential divergence presents an opportunity. A particular virtue of the CBAM is that it is one of the few proposed international mechanisms to promote compliance with the climate goals outlined at COP26 – which otherwise remain dependent on nearly 200 nations living up to their individual commitments and effectively marking their own homework. So, the CBAM may well be important to how history judges the summit and post-Brexit Britain’s first major outing on the global stage. But the EU has little chance of implementing it without active cooperation from the US.

At the same time, an EU-US deal on the CBAM could be damaging for the UK – which has relatively large iron, steel, and aluminium exports to the EU. For all these reasons, the UK should help the EU shape the still largely unformed CBAM. In particular, it could help the EU design the policy to recognise the technological effort that both the US and the UK are making, as well as their overall success in reducing carbon emissions even outside the sectors that the CBAM would regulate. The UK will need American help in this effort, but it is in a better position to shape the CBAM than is the US, which is burdened by its domestic climate disputes, its reputation of climate scepticism, and its relative lack of understanding of policymaking in Brussels.

Technology regulation and investment screening

Increased Chinese investment in Western markets, particularly in high-tech industries, has spurred efforts on both sides of the Atlantic to screen foreign investment into strategic industries. Since the 1970s, the US has had a centralised procedure for investment screening that revolves around the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), an interagency committee that makes recommendations to the president on whether to block foreign investments in the interests of national security. In recent years, the US has reformed the system to address the threat of Chinese investment in high-tech sectors.

In confronting the same issue, the EU had to design an investment screening system largely from scratch. This system came into full force in October 2020, in line with the regulatory framework the union laid out in March 2019. As the first EU-wide foreign investment screening cooperation mechanism, the system is a big advance in EU economic governance – but it is still incomplete. Several member states have decided not to engage in investment screening, and those that have apply a wide range of criteria and procedures. At the same time, procedures under the system are so complicated that the European Commission’s role in the process is unclear – it does not have the power to directly block investments, but it is essential to establishing a coherent EU-wide approach to investment screening. The Commission’s main purpose is to prevent third countries, including both China and the UK, from negotiating investments in strategic industries bilaterally with sometimes vulnerable member states.

The EU seeks cooperation with third countries on policies and practices related to investment screening. The Biden administration also wants to create a link between the CFIUS and the European Commission’s screening authorities, to ensure that they regularly share intelligence. They probably need each other: Separately, Americans and Europeans both lack the analytical tools to effectively distinguish between strategically motivated takeovers and those that might promote fair competition, innovation, and growth. Together, they can get a fuller picture. Transatlantic cooperation is, therefore, essential to preventing counterproductive decisions in the area. Accordingly, the EU-US Trade and Technology Council identifies investment screening as an area of cooperation, but without explaining how this would work.

All this presents another opportunity – and a challenge – for the UK. It is a challenge because an EU-US investment screening system formed without UK input would essentially force the UK to follow suit. Otherwise, the UK would risk becoming a dumping ground for strategic investments from China and elsewhere that seek a backdoor into EU or US markets, corrupting its home market and straining its relationship with both parties. It is an opportunity because, if the UK can help shape the investment screening systems of the EU and the US, it can ensure that the system meets its own security and economic needs – and that it does not discriminate against UK investments in the EU and the US.

Of course, neither the EU nor the US particularly wants the UK to have a significant role in reforming the process of investment screening. The UK would have to prove its value – but it could do so by demonstrating the possibility of aligning its relatively American-style system of economic governance with the complicated EU investment screening structure. The UK’s newly passed National Security and Investment Act is already aligned with the overall objectives of the EU regulation. There remain significant differences between them in the sectors and assets they scrutinise. But the act is still noticeably more aligned with the EU’s approach than is the US one, which is a legacy of the cold war.

It would be easier for the EU to align with the UK than the US on investment screening. Such an EU-UK alignment could then set the direction and basic outline for a future EU-US agreement on the issue – in a manner that served the UK’s interests, not least by allowing London to participate in negotiations on the deal.

Operating principles

The CBAM and investment screening are only two very specific issues – they are important but unlikely to make many headlines. At the same time, they are representative of a whole host of issues that, collectively, will matter a great deal. For example, the UK has an opportunity to shape how it, the EU, and the US collectively decide on and apply sanctions. It has the potential to use its relationships with the US and EU to determine how Chinese technology such as Huawei 5G infrastructure is evaluated for security risks. And it could leverage its relationships with the US as the pre-eminent financial centre and the EU with its regulatory machinery to ensure that the UK financial industry can thrive in the years to come. All this is possible. But the UK is unlikely to make progress without a mature and effective political relationship with the EU. The country can establish such a relationship if it adopts a few general operating principles for a more realistic, yet still independent, British foreign policy.

Firstly, the UK needs to resist the impulse to ignore the EU and generate serial existential crises over relatively minor issues, such as sausage imports and fishing. The current British government seems to find domestic political nourishment in permanent Brexit, but this hinders British foreign policy. Of course, the UK’s relations with key EU member states are more important than its relationship with Brussels. But these states all depend on the EU. A reflexively anti-EU stance alienates the UK from its European partners. And it makes the country dependent on the US, reducing its influence on both sides of the Atlantic.

Relatedly, the British government needs to avoid slavishly following Washington’s desires on foreign policy issues, particularly where these cut against British interests. Here, the government has had a mixed record. For example, it closely aligned with its European partners on the Iran nuclear deal and climate change issues even when the Trump administration was pushing hard in the opposite direction. But, on issues such as China, the UK has been anxious to resume its questionable role as a junior partner. Of course, the UK also has its own reasons to worry about China. But, regardless, when the UK implies that the US government needs to offer little in return for British support, that is precisely what it gets.

Once the British government re-establishes an effective working relationship with the EU, it will need to resume its efforts to shape the EU’s regulatory power and, accordingly, its foreign policy.The EU has an enormous capacity to set the regulatory agenda for the world, as it has demonstrated on issues such as privacy and competition policy. The UK, in turn, has enormous potential, as a non-member, to influence the EU on such issues and help shape the union’s regulatory policy in areas that are important to British foreign policy, ranging from technology standards to animal and plant health. Few countries, including EU member states, understand the EU system of policymaking as well as the UK – and even fewer have such a depth of official expertise at exercising subtle influence in complicated negotiations. However, this unique British asset will turn to dust if the UK makes no effort to improve its political relationship with the EU.

Conclusion

As an enterprising middle power that seeks to both protect its sovereignty and hold its own in a geopolitically competitive environment, the UK needs to play to its considerable but specific strengths. It cannot hope to excel across the spectrum of capabilities and issues. The British military, despite its grand traditions, no longer provides the relative advantage for the UK that it once did. Rather than looking backwards to a misremembered nineteenth century and across the world to a distant Indo-Pacific, the UK can gain the prosperity and respect it craves by focusing on its unique capacity to work well with a variety of partners, particularly the EU and the US, and by relying on its privileged position in international institutions, its world-class diplomatic corps, and a careful effort to nurture its still-considerable soft power.

As ECFR’s new survey shows, this is a foreign policy that could command the support of a British public that values its sovereignty. The current British government, by contrast, has defined itself and its ideology in opposition to the EU, thereby cutting itself off from a more flexible and independent approach. The survey demonstrates that the government’s ideology reflects the anti-EU views of its Conservative voter base but not that of the broader UK population. More pointedly, it shows that the public – including Conservative voters – do not have strong opinions on the EU or many other aspects of foreign policy. A very different kind of foreign policy would be a viable political option for a future British government, even one led by another Conservative politician.

Global Britain is a delusion. But there is a foreign policy that can command the support of the British public and map out a secure and influential future for the UK. The real question is whether the British people will find a government with the wit and the will to seize that future.

Methodology

This paper is based on a public opinion poll that the European Council on Foreign Relations commissioned from Datapraxis and YouGov. The survey was conducted in the UK between 20 and 22 October 2022, on a sample of 2,019 respondents. The general margin of error is ±2 per cent. This was an online survey. The results are nationally representative of basic demographics and past votes. YouGov used purposive active sampling for this poll.

About the authors

Jeremy Shapiro is the director of research at the European Council on Foreign Relations and a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. He served at the US State Department from 2009 to 2013.

Nick Witney is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He joined ECFR after serving as the first chief executive of the European Defence Agency. His earlier career was spent in British government service, as a diplomat (in the Arab world and Washington) and, later, at the Ministry of Defence, where he served as director-general of international security policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would firstly like to thank the government of Boris Johnson for its unwavering adherence to foreign policies that they find deeply unwise. Without that inspiration, this paper would be at best unnecessary, at worst boring. So, thank you, prime minister et al. Keep on being you.

The authors also owe a deep debt of gratitude to Isabella Antinozzi, who provided expert research assistance, an entirely positive attitude, and a deeply devastating critique. It is rare to find one’s most helpful resource and one’s most trenchant critic in the same place, but she gamely filled both roles with expertise and panache. The authors also owe thanks to Mark Leonard and Susi Dennison for their sage advice and close reads of the more outlandish drafts of the paper. They owe Chris Raggett and Marlene Riedel immense thanks for their expert editing and their graphics acumen. This paper began with a Foreign Affairs piece entitled ‘The Delusions of Global Britain’, published in March 2021. They owe huge thanks to Daniel Kurtz-Phelan and Rhys Dubin at Foreign Affairs for the inspiration to write that article and then to move beyond it with this paper.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.