Ambiguous alliance: Neutrality, opt-outs, and European defence

Summary

- EU member states that are neutral or militarily non-aligned, or that have an opt-out from common defence, are often overlooked in discussions about European defence.

- The existence of these special status states not only creates uncertainty about the EU’s ambitions to become a fully fledged defence union but also calls into question the functionality of the mutual defence clause, Article 42.7, in the long run.

- The special status states fall into three groups according to the challenges they pose to the EU: the “non-aligned in name only” (Finland and Sweden); the “odd one out” (Denmark); and the “strategic schnorrers” (Austria, Ireland, and Malta).

- The EU’s work on its Strategic Compass should include debates on the special status states’ future role in European defence, as well as discussions on the operationalisation of the union’s mutual defence clause.

Introduction

When Austria applied to join the European Communities (EC) in 1989, the European Commission opined that the applicant’s “permanent neutrality” would be incompatible “with the provisions of the existing treaties” and would pose a problem to “the obligations entailed [by the EC’s] future common foreign and security policy”. Still, in 1993, shortly after the Maastricht Treaty converted the EC into the European Union and established the Common Foreign and Security Policy, the bloc launched accession negotiations with neutral Austria. The country became a member of the EU in 1995.

Austria is not the only state that has joined the EU or its predecessor organisations despite being neutral. Ireland joined the EC in 1973. Finland and Sweden became members of the EU in 1995; Cyprus and Malta in 2004. These six countries self-identify as “neutral” or “non-aligned”. Some of them have enshrined this status in their constitutions; others’ neutrality is less formalised but no less ingrained. While neutrality remains a somewhat elusive and ambiguous concept in international relations, experts generally agree that neutral states are prohibited from joining military alliances. This is why none of the six neutral states is a member of NATO. They are, however, members of the EU – whose declared aim is to become a “fully-fledged European defence union” by 2025.

This goal might give the non-aligned states pause, as it seems at odds with even the minimalist interpretation of neutrality. Alongside the neutral countries, there is a seventh member state for which the EU’s efforts to become a more coherent and stronger actor in the defence realm could cause concern: Denmark. The country joined the EU in 1973. It is a founding member of NATO. However, following a domestic referendum held after the adoption of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993, Denmark decided to opt out of European defence. As a result, it has followed recent EU defence efforts mainly from the sidelines. This publication refers to the seven EU countries that are neutral or non-aligned, or that have a defence opt-out, as “special status states”. It does not cover Cyprus – which, as a divided and partially occupied EU country that is in conflict with Turkey, presents different challenges than the other six states.

Admittedly, the EU’s interest in defence comes and goes, depending on threat perceptions and member states’ engagement with the issue. For many, the EU remains a primarily economic project. But the ambition to become a security and defence alliance is as old as the union itself, with some of its members having discussed plans for a ‘European army’ as early as the 1950s. The EU established the Common Security and Defence Policy two decades ago. Over the last few years, the EU has considerably stepped up its efforts in the defence realm – driven by a heightened sense of insecurity following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the election of Donald Trump as US president in 2016, and the United Kingdom’s 2016 decision to leave the bloc. Initiatives such as Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Defence Fund are meant to increase cooperation on defence projects and foster a sense of military solidarity across the EU. (Interestingly, some European leaders have recently described these efforts as “strengthening the European pillar of NATO”, thereby effectively disregarding the existence of neutral and non-aligned states.) Furthermore, the EU aims to become a stronger geopolitical actor by increasing its ‘strategic autonomy’ – its capacity to act independently and to safeguard its interests in the international realm. In 2020 the union embarked on the two-year development of a Strategic Compass that, based on a common threat analysis, aims to define the EU’s level of ambition as a security provider.

A defence union or a military alliance?

None of these defence efforts or stages of European integration prompted Austria, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Malta, or Sweden to leave the EU or avoid joining it in the first place. Most importantly, the countries remained EU members when, in 2009, the bloc introduced its mutual defence clause, Article 42.7 of the Lisbon Treaty.

Article 42.7 obliges EU countries to aid a fellow member state that becomes “the victim of armed aggression on its territory” by “all the means in their power”. This formulation is reminiscent of the better-known Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which calls on NATO member states to assist a party being attacked “by taking forthwith … such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force”.

Article 42.7 Lisbon Treaty (EU)

“If a Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power, in accordance with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. This shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain Member States.

Commitments and cooperation in this area shall be consistent with commitments under the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, which, for those States which are members of it, remains the foundation of their collective defence and the forum for its implementation.”

Article 5 Washington Treaty (NATO)

“The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognised by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area …”

Reading Article 42.7, one could conclude that the EU already is, in fact, a defence alliance. At a minimum, it raises questions about how the neutral states square the circle of being a member of a union that has a mutual defence clause while upholding their non-aligned status. The EU attempts to address this contradiction in the article, stating: “this shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain Member States”. This provision, also known as the ‘Irish clause’, is generally understood to refer to the neutral or non-aligned EU member states, effectively giving them an opt-out from EU mutual defence in case of an attack. As this essay collection shows, the special status states differ to a surprising degree in their interpretation of the applicability of Article 42.7. And it is unclear whether Denmark’s opt-out applies to Article 42.7. This became evident in 2015, when the article was invoked for the first (and, so far, only) time following the Paris terrorist attacks. Many EU states provided help to France in different ways. Some special status states took action, while others did not.

Dangerous ambiguity or a clever way forward?

Thus, the story of the special status states in the EU is about ambiguity. Neutrality is a contested concept. And Article 42.7 leaves more room for interpretation than one might expect for a clause in a legally binding text – what, for example, are “all the means in [member states’] power”? This is exacerbated by the Irish clause, which introduces further uncertainty about which countries are subject to the article. The EU has a history of strategically employing ambiguity in internal and external discussions. It is a tactic that deliberately leaves room for interpretation so that potential supporters can project their wishes onto an idea, even if there is no consensus on its actual meaning. But what may work in theoretical debates about strategic autonomy is much more dangerous and inadvisable in its practical applications, especially in the defence realm. There is no harm in ambiguity over the level or type of autonomy Europe strives for, particularly if this allows for step-by-step developments. But ambiguity over whether and how many firefighters respond to an emergency call appears to be considerably more problematic.

Mutual defence agreements live and die on certainty about the actions of one’s allies. This is why Europeans were so unsettled by Trump’s questioning of the US commitment to Article 5. But, when it comes to Article 42.7, ambiguity is everywhere. If the EU’s aim is to become a defence union, and able to do more without support from other actors such as the US, it will need to operationalise – and clarify member states’ responsibilities under – Article 42.7 (as Germany, France, Italy, and Spain recently called for in a joint declaration). If it does so, the EU will need to look at states that stand apart, one way or another, on defence.

This essay collection looks at these special status states, focusing on what their EU membership means for European defence and the bloc’s future ambitions. It discusses the ways in which these countries reconcile the mutual defence clause and growing European defence cooperation with their special status. Do they feel bound by Article 42.7 and buy into the ambitions of a defence union? And, if they are willing to contribute, would this be compatible with their domestic laws, today or in the future?

To answer these questions and shed some light on what this ambiguity will mean for European defence and the EU’s ambitions to become a defence union, we turned to experts from the special status states. The essays at the heart of this publication were written by Gustav Gressel (Austria), Christine Nissen (Denmark), Tuomas Iso-Markku and Matti Pesu (Finland), Clodagh Quain (Ireland), Roderick Pace (Malta), and Calle Hakansson (Sweden). The six essays are similar in structure to allow for direct comparisons on key issues, including their current level of engagement in EU operations, the way they reacted to France’s invocation of Article 42.7, and their national debates.

Analyses of EU politics seldom group these states, and they rarely work together, in the way that, for instance, several eastern European countries do in the Visegrád group. The essays help illustrate why this is the case. The special status states may have some shared characteristics, such as their comparatively small size: Sweden is the largest of the group, with ten million inhabitants; Austria has nine million; and most of the others have around five million – the exception being Malta, with only 450,000. But the states also differ on many points, not least the precise characteristics of their special status: for some of the countries, such as Austria and Finland, it was the post-second world war world that led them to adopt non-alignment, while Sweden has not formally taken sides in a war since Napoleon was advancing across Europe. Malta only anchored neutrality in its constitution in 1987, and did so primarily for domestic reasons, while Ireland’s neutrality is not enshrined in domestic law or any international treaty. Their security situations and concerns, and their military capabilities, vary widely – which ultimately influences how they see and approach EU defence efforts.

Can the EU reach its goal of becoming a fully fledged actor in international security and defence while it includes seven special status states that, for various reasons, may be unable or unwilling to fully buy into mutual European defence? Might it only achieve this through fragmentation or the creation of a ‘multi-speed Europe’? And, if some states are more equal than others when it comes to mutual defence requirements, is there a danger that they could face accusations of free-riding? The EU would be well advised to use the development of its Strategic Compass to discuss these and similar concerns regarding the special status countries. This essay collection aims to contribute to that process.

Free-rider for life: Austria’s inability to fulfil its defence commitments

- EU member since: 1995

- Neutral since: 1955 (treaty with powers that were victorious in the second world war)

- Population: 9 million

- Current defence spending as a share of GDP: Approximately 0.7 per cent

Number of troops: Active: 22,050 (including conscripts and non-combat administrative personnel); reserve: 33,000 (10 battalions totalling around 3,000 cadres, which are trained reserves; the remaining reserve force exists only on paper, as it does not receive training and hence cannot be deployed in a crisis or war).

Surviving by luck

Austria’s neutrality was prescribed in the 1955 state treaty concluded between the country and the four then-occupying powers: Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States. The treaty placed a series of restrictions on Austria’s military not to develop certain capabilities and to refrain from engaging in various forms of international cooperation and organisations (some of which the government has since lifted). However, most restrictions were put into the treaty not to prescribe neutrality but to prohibit any approximation, assimilation, or de facto integration with Germany (Anschlussverbot). Austria adopted permanent neutrality in the form of constitutional law on 26 October 1955. However, it has amended and reinterpreted the law several times since then. In a nutshell, Austria is not allowed to join a defensive military alliance (one with a common defence clause such as Article 42.7 of the Lisbon Treaty or NATO’s Article 5) nor to host permanent foreign military installations on its soil.

While the Austrian political establishment agreed on and advocated the basic exchange of sovereignty for neutrality shortly after the re-establishment of the state in April 1945, tensions and conflicting interests prevented the deal from being concluded for another decade. The Soviet Union wanted to make Austria a role model for other European states to withdraw from the formation of NATO, while the US tried to buy time to build up a more resilient state apparatus. In the end, they both failed: Austria was neither a role model for anyone else nor a resilient neutral state that could take care of its own security, such as Switzerland.

Unlike Finland, Sweden, Switzerland, and Yugoslavia, Austria would not have tried to defend itself independently if the cold war in Europe ever turned hot. In the event of a conflict, the army was set to symbolically “fire five shots at the border”, as former foreign minister and chancellor Leopold Figl put it. And then Austria would de facto rely on NATO’s interest in defending or liberating the country for the sake of its own security (though Vienna always overestimated its willingness to do so).

This complacency nearly ended in disaster. When in 1968 Warsaw Pact troops intervened in Czechoslovakia, they also prepared a further advance into Austria. To this day, it is still unclear exactly when and why the Soviet leadership decided that “Operation Danube” (the codename for the intervention) did not reach the river for which it was named. Despite engaging in a deep reform of its armed forces and military doctrine thereafter, Austria never invested enough resources in its defence to be sufficiently resilient.

This lack of resilience was not confined to the defence sector. In the late 1980s, a series of scandals shook the small republic, revealing that – with the help of communist intelligence agencies and dubious brass-plate enterprises – some members of the political elite were engaged in businesses such as the illegal arms trade, large-scale insurance fraud, murder, and smuggling. They had often dragged captured state institutions into these enterprises. The dire state of Austria’s domestic politics was one incentive for it to seek membership of the European Economic Community by the end of the 1980s – reasoning that the European framework would provide some safeguards against domestic failings.

However, Austrian leaders hardly seemed to have learned – or had quickly forgotten – the lessons of the cold war. The European Union’s nascent foreign policy barely featured in the 1995 accession round. Because militarisation was unpopular domestically, Austrian politicians reassured the public that European defence policy would be compatible with neutrality – even though experts disagreed.

Early discussions of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) revolved around international stabilisation missions. As Austria had participated in UN missions since the 1960s, its involvement in those missions under the auspices of the EU never triggered the kind of debate about compatibility with neutrality that occurred in Switzerland.

Indeed, Vienna was eager to contribute to the international stabilisation missions in the Balkans, including Operation Alba in Albania (1997); the Kosovo Force (since 1999); the Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina, along with its successor mission (since 1995); and EUFOR Concordia in Macedonia (2003). This is because it was in Austria’s interest to stop the bloodshed near its borders. Most Austrians saw these missions as justified, with only a few groups on the ideological fringes challenging them. Hence, the Constitutional Court dismissed challenges to amendments to the Wehrgesetz and KSE-BVG, the laws on the armed forces and on deploying soldiers abroad respectively.

However, Vienna lost interest in robust missions once some EU and NATO operations moved beyond the Balkans. The deployment of a single special forces company to EUFOR Chad in 2007-2008 was the peak of Austria’s contribution to robust EU missions. The contribution drew heavy criticism from both the left and the right: how dare the government expose soldiers to the risk of fighting? After it became publicly known that Austrian soldiers shot and killed rebels (in a legitimate act of self-defence), no Austrian minister of defence tried to participate in a demanding military operation ever again.

Since then, Austria has made only non-combat contributions to the Common Security and Defence Policy, including through civilian missions, observer and training missions, and logistical support (such as supply and maintenance services) for EU battlegroups. Austria’s defence ambitions were in a steady decline.

No need for an army

One could endlessly debate the political and legal arguments that Austrian politicians and scholars make for why Austria should not abide by Article 42.7. But the defining factor in the Austrian Sonderweg (special path) is less the country’s legal restrictions or tradition of free-riding than a structural factor: its lack of armed forces with which to fulfil a defence commitment. Of course, on paper, Austria has armed forces – the Bundesheer. But, in practice, the combat readiness and capabilities of the organisation would not allow it to conduct any war-fighting operation.

In 2018 Austria’s technocratic caretaker government issued an honest assessment of the status of the armed forces and the capability shortfalls that have accumulated over time. The conclusion was that the armed forces would need an additional €16 billion of investment in equipment and an increase in the defence budget from €2.4 billion to at least €3.3 billion – roughly equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP – to be able to counter hybrid threats (such as those from state-sponsored insurgents, including the Turkish-backed Grey Wolves and Russian-sponsored illegal armed groups) or provide rear-echelon services in a crisis (such as the protection of critical infrastructure, and of EU military convoys passing through Austria). If the army wanted to consider fighting another peer competitor as part of an Article 42.7 joint defence operation, it would require an even larger investment. This is because the technological capabilities of powers in Europe’s vicinity – particularly Russia – have increased dramatically since the end of the cold war. Austria, in contrast, has for decades lacked critical capabilities, such as an air force capable of engaging ground targets. This means that it would require an enormous investment in training and education to achieve even minimal interoperability with other European armies. The report stated that, in essence, the Jagdkommando Special Forces are the only sufficiently trained and combat-ready part of the military. But they would be overstretched in any scenario beyond an isolated terrorist attack on Austria.

Addressing these gaps would also require organisational and legal reforms. The six months’ term for conscripts is too short to train personnel properly. The current system – which gives soldiers lifelong employment schemes like all other civil servants – has contributed to ageing the force. The expansion of the military bureaucracy, designed to find employment for elderly soldiers who can no longer serve in the field, consumes more and more resources. But, because all reforms since the end of the cold war have been conceived of by these ageing soldiers, they usually involve cuts to military capabilities. Reforms of the administrative bodies were window-dressing, at best.

After coming to power in January 2020, the new ‘political’ (as opposed to caretaker) government reverted to the long-established practice of adapting reality to political preferences. The new minister of defence declared that Austria was unlikely to face the threats covered in the report cited above: increasing tensions between the EU and Russia; deepening military and geopolitical tensions in the Mediterranean; and growing risks from globalisation such as pandemics, cyber attacks, and strategic terrorism. Hence, she argued, there was no need for defence capabilities. The armed forces would “reform and restructure” to serve as an auxiliary force for domestic security and disaster relief operations, reducing defence capabilities “to a minimum” (as if there were any in the first place) to save funds.

So, whatever defence ambitions the Austrian government may declare in Brussels, there is no army capable of fulfilling them. Therefore, Austrian political elites – regardless of their political orientation – are mainly interested in engaging with EU defence structures to limit these ambitions, lest Austria reveal its weakness in military matters. Austria was eager to join Permanent Structure Cooperation (PESCO), but not to contribute too much or to pick demanding projects (it has joined a cyber security programme with Greece, a disaster-response programme led by Italy, a military transport initiative, and the German-led centre for training missions). While Vienna sits at the table, it could use its position to block an increase in PESCO’s ambitions – even if, currently, there seems to be no danger that this will happen.

Austria and the EU’s mutual defence clause

When Austria joined the EU, the CFSP had no dedicated military dimension and the need for unanimity often allowed neutral states to opt out of defence-related initiatives. On paper, this reconciled the conflicting demands of EU membership with permanent neutrality as adopted into constitutional law. It became more difficult to justify Austria’s participation under the ESDP and missions that could involve military action. The reasoning for this approach was that EU missions and sanctions would be based on UN mandates. States’ obligations under Article 103 of the UN Charter prevail over other international commitments, such as neutrality. As the state treaty was concluded after the advent of the UN Charter – and as Austria had been a member of the United Nations since 1956, and had participated in UN missions since 1960 – the organisation of UN-mandated missions through EU structures would not dramatically change the country’s practices.

However, the Austrian debate always referred to out-of-area missions as a cause for concern. From an Austrian point of view, it was clear that Austria would never take part in any collective defence operation, regardless of its legitimacy. In the Austrian interpretation of Article 42.7, the so-called Irish clause (which says that the treaty “shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain Member States”) would exempt Austria from participating in military action in response to military aggression against another EU member state. As a last resort, Austria would use its sovereign veto to prevent any European Council decision that would demand military assistance for the target of such aggression.

This rigid, isolationist stance is paramount among all political parties. There was a brief period between 2000 and 2002 when the ruling coalition – comprising the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) and the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), and led by Wolfgang Schüssel – advocated a common defence clause for the EU. Joining NATO, as envisioned by the FPÖ and parts of the ÖVP in the 1990s, would have been political suicide given public resistance to the move. So, transforming the EU into a defence alliance would serve as a back door through which to finally make neutrality obsolete. However, the domestic debate shifted against any such endeavour due to left-wing populist opposition to Austria’s ‘militarisation’, the romanticisation of neutrality, growing anti-Americanism in the wake of the Iraq war, and increasing public discontent with the EU after the bloc opened accession talks with Turkey.

The conservative ÖVP (which is now a much more populist party than it once was) quickly ended its flirtation with deeper defence integration. And the FPÖ dropped out of government, split, collapsed into chaos, and eventually reconstituted itself around its national-socialist core, rejecting internationalism of any sort. In this new form, the FPÖ came to love both neutrality and Russia even more fiercely than the left did.

On the domestic front, neutrality is popular across all parties. What was predominantly an issue for the left during the cold war became part of the national consensus, maintaining a steady approval rating of around 70 per cent. Therefore, the few Austrians who know that EU membership and neutrality are at odds with each other – mostly academics, diplomats, and security officials – dare not discuss this in public, as they fear the erosion of the minimal consensus on formal ESDP participation that lingers from the 1990s. Austria has commissioned little doctrinal or legal work on how it would behave if another member state demanded military assistance under Article 42.7. Pushing politicians to address the issue could backfire and deepen Austria’s isolation on defence issues within the EU.

Moreover, there is no established EU procedure for responding to such a call. When France asked for assistance after the Paris terrorist attacks in 2015, the EU Council held no dedicated meeting on how to provide this. Instead, France approached each EU member state individually to ask them what they intended to contribute. Unsurprisingly, Austria did not contribute anything. There was no big debate about this in Vienna – in effect, the country just looked the other way.

Meanwhile, there has been little debate on ‘strategic autonomy’ in Austria. Although anti-Americanism is widespread in all Austrian parties, and Vienna was the member state capital most opposed to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, this has not translated into public support for the creation of independent European military capabilities. The Ministry of Defence tried to use the debate on strategic autonomy to advocate for more ambitious military contributions to EU missions (hoping that this would also lead to increased funding), but the discussion never went beyond bureaucratic politics and discussions between experts. Among the political class, the rationale that there is no need for an army always prevails.

Future policy

It is hard to predict how Austria will behave in any military scenario, because there is little policy debate on the issue. What debate there is involves bureaucratic politics: the foreign ministry and the armed forces try to use the EU’s agenda to ensure their own survival. But this debate, regardless of its nuances, does not reflect any foreign- or defence-policy ambition of the political class – which has none.

In the past two decades, the Ministry of Defence has been presided over by various socialist, conservative, and right-wing (FPÖ) ministers, who theoretically presented different visions for defence. In practice, the ministry has done nothing apart from gradually abandon the military’s war-fighting capabilities, while finance ministers have (regardless of their party) set increasingly restrictive budgetary limitations on the armed forces. Each minister tasked the defence bureaucracy with drafting and implementing reforms in line with the diminishing budget, prompting it to preserve offices, academies, committees, administrative staff, and events at the expense of war-fighting capabilities. The ministers’ justifications for the reforms varied according to their ideologies. But the end result was always the same.

This structural limitation would prevent Austria from changing its defence policy quickly, even if it wanted to. The country could not reconstitute the armed forces overnight simply by purchasing fancy equipment. The effectiveness of an armed force primarily depends on its soldiers and commanders – their training and tactical and operational versatility. As a result of limited funds and the short duration of conscription, the Austrian military has cut its manoeuvres to a minimum. At least one generation of officers have trained with just peacekeeping in mind, and have only heard about combined arms manoeuvres at the planning table or in wargames.

Furthermore, the Austrian armed forces have always lacked critical capabilities compared to NATO armies in areas such as air warfare (in all forms, including air-to-ground coordination), electronic warfare, and precision strike. Therefore, they could not operate in the same line as NATO ground or air forces. The official defence policy, regardless of the different ideological camps it may emerge from, merely serves as a smokescreen for unpreparedness. When Austria is in search of an excuse for this situation, a rigid interpretation of neutrality comes in handy.

If another EU member state asks for military assistance under Article 42.7, the key question in Vienna will concern not whether this is compatible with neutrality but whether the smokescreen will hold. In the case of an event that requires only a minimal, symbolic contribution (such as a terrorist attack), Austria may indeed consider making one. On terrorism, Austria once showed a kind of “neutrality” even towards the Islamic State group: it has turned a blind eye to the movement of fighters to Syria and the presence of jihadist networks on its soil, in the hope that many of them will die fighting in the Middle East instead of posing problems at home. Nonetheless, the terrorist attack in Vienna in November 2020 exposed this negligence and has led to a certain change of course on domestic security.

But Austria would rely on neutrality to preserve the smokescreen in the case of more dramatic events, such as Russian tanks rolling into Finland or Turkish tanks into Cyprus (as they are not members of NATO, Finland and Cyprus could call for assistance from the EU under Article 42.7). Given its difficulties in dealing with even hybrid threats such as state-sponsored insurgent groups, Austria would have to balance the risk that an aggressor would launch a retaliatory attack against it with pressure from its EU peers to show solidarity by granting military convoys the right to pass through its territory on the way to the theatre of operations. Depending on the specific circumstances of the crisis, Austria could passively tolerate collective defence operations by other EU member states or openly oppose them (such as by blocking measures in the European Council or refusing to allow access to its territory).

The Austrian public mood on these issues hardly matters, as Vienna does not foresee a scenario in which it would have to call for such assistance or solidarity from other EU members. Because it is surrounded by NATO states, Austria effectively rests its national defence strategy on other European countries and the US. If an aggressor shattered these defences and advanced towards the Austrian border, it would be too strong for Austria to fend off anyway. This is why Vienna sees free-riding as the most rational choice. Survival by luck worked for Austria during the cold war and has shaped its national security identity – and, for now, there is no prospect that this will change.

Sovereignty concerns: Denmark’s opt-out from EU defence

- EU member since: 1973

- Opt-out of EU defence: 1993 following a referendum

- Population: 5.8 million

- Current defence spending as a share of GDP: Approximately 1.5 per cent planned for 2021

- Number of troops: 15,400 active and 44,200 reserve

Denmark’s special status: opting out of EU defence cooperation

Denmark’s exemption from the defence-related aspects of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) gives it a unique perspective on EU security and defence issues. It appears an anomaly that Denmark has voluntarily and permanently opted out of EU defence cooperation. Denmark is not a neutral state and regards itself as being a principled foreign policy actor striving to make an assertive contribution to the international community, not least by making a considerable contribution to international military operations. Denmark also has a long history of engagement with European integration, having joined the European Union in 1973.

That said, concerns about the EU’s impact on national identity and a fear of losing sovereignty has long characterised the Danish perception of EU membership. This resistance is reflected in national referendums in which Danes have often voted ‘no’ to further EU integration. This was not least the case with the Maastricht Treaty’s aspirations of increased cooperation in policy areas where Denmark was particularly reluctant to surrender authority, including the creation of a common security and foreign policy. With its vote against the ratification of the treaty, Denmark came close to killing it entirely. To allow other members to move forward, EU heads of state made the Edinburgh Decision – which established several opt-outs for Denmark so that it could ratify the treaty.

The EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) framework emerged a decade later, but Denmark was still unable to participate in EU military operations or in any decisions or planning in this regard. The opt-out also prevented Denmark from participating in: the European Defence Agency, which the EU established in 2004 to help member states develop their military capabilities; the relevant CSDP provisions of the Lisbon Treaty (which entered into force in 2009), including Article 42.7 on mutual defence; or in Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), which the bloc launched in 2017.

However, the opt-out is limited to activities that have both defence implications and a legal basis in the CFSP provisions of Articles 42-46 of the Treaty on European Union. Whether an activity has such implications is a matter of legal interpretation on a case-by-case basis, making the design of the opt-out somewhat flexible. From the outset, Denmark has been able to take part in civilian CSDP missions.

The EU’s defence activities have recently moved beyond the CSDP by strengthening the role of the European Commission. Accordingly, Denmark has participated in new defence initiatives that have a non-CSDP legal basis. This includes initiatives such as the European Defence Fund, new cooperation on military mobility, and the European Peace Facility (which is designed to bolster external action on peace and security). Thus, the opt-out is not all-encompassing.

Denmark’s level of ambition and the mutual defence clause

Denmark finds itself in an odd position in efforts to strengthen EU integration, as the opt-out is constructed in such a way that the country has no influence over EU defence cooperation. The opt-out says that Denmark: “will not prevent the development of closer cooperation between member states in this area”. As it cannot block integration it has chosen to keep out of, Denmark has effectively reduced its power in the European Council at its own request. Thus, while the creators of the opt-out framed it as a way to retain sovereignty underpinned by legal guarantees, the measure de facto means that Denmark has lost strategic control over its participation in EU defence initiatives.

This loss of influence was evident when the Lisbon Treaty, including Article 42.7, entered into force. Since Danish scepticism centres on a fear that the EU will gain too much autonomy at the expense of NATO, Article 42.7 goes against Danish interests. Nevertheless, it was other member states that pushed for this measure. Moreover, since the clause is part of the legal articles that are explicitly covered by the opt-out, Article 42.7 article has very few implications for Denmark.

This might help explain why the article had no impact on the Danish public debate. But it has become the norm in the country only to discuss EU defence matters in a limited fashion – usually in ‘yes or no’ types of conversation that leave little space for nuance. One can ascribe the lack of debate on such matters to the opt-out, which discourages Danish voters, politicians, researchers, and civil servants from thinking about the union in relation to defence and security.

When the French president invoked in 2015 the mutual defence clause for the first time – following the Paris terrorist attacks – the Danish media hardly noticed. However, the French request elicited a surprising reaction from the Danish government. Following discussions at the EU Council to invoke Article 42.7, the Danish foreign ministry set out to explore whether Denmark could support France under the auspices of Article 42.7, despite the opt-out.[1] Here, the ministry’s legal service concluded that, if Denmark referred to Article 42.7 or even invoked it itself, this would not automatically activate the defence opt-out. The opt-out would only be triggered if the actions that followed the invocation of Article 42.7 were rooted in Articles 42-46 and had defence implications.[2] Article 42.7 allows states to engage in defence activities outside the EU context following its invocation. Accordingly, the Danish authorities concluded that any bilateral contribution to the French request would be unproblematic – even though the opt-out explicitly covers the mutual defence clause.

On 17 November 2015, Denmark stepped up its counter-terrorism operations in Mali at France’s request. The Danish Parliament decided to strengthen the country’s engagement with the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali, which Denmark had contributed to since its launch two years earlier. The Danish Parliament mentioned the EU – though not Article 42.7 – as a primary reference point for the mission. And the then-foreign minister, Kristian Jensen, hinted that the French request was one of the reasons why Denmark wanted to increase its involvement in the Sahel.[3]

Denmark’s response to the French invocation of Article 42.7 is in line with its broader approach to the debate on European ‘strategic autonomy’. By default, Denmark stands outside any type of increased EU defence cooperation. In practice, however, the country is keen to be a pragmatic partner on European security matters and will accommodate any such cooperation it sees as beneficial.

Generally, Denmark has been sceptical of the rhetorical aspects of the debate, although it largely agrees with its content. The country sees that there is an increasing need for the EU to be capable of protecting its international interests, not least when it comes to issues that go beyond military cooperation and territorial defence. Here, Denmark’s push for a broad use of EU policy tools reflects the complex pattern of threats Europe faces, in which insecurity stems not only from military affairs but also other areas of society, such as trade, technology, and critical infrastructure.

Copenhagen fears that strengthened European strategic autonomy could be interpreted as an alternative to NATO and the transatlantic relationship. Denmark has sought to adjust the language around the concept and limit references to it in European Council statements. The Danish position is that strategic autonomy should strengthen the transatlantic relationship and increase cooperation with non-EU countries. As such, Denmark believes that the EU has good reasons to gain more autonomy and thereby take greater responsibility for security cooperation with the United States.

The future of Denmark’s special status

Despite the opt-out, Denmark has participated in the recent scenario-based exercises designed to test the mutual defence clause – the first of which, focused on hybrid warfare, occurred in January 2021, and was followed by two others. The exercises are designed to create a common understanding of the operationalisation and possible use of the clause. In this regard, Danish policymakers foresee difficult negotiations on EU defence cooperation in which they will have to figure out how to position their country.

The applicability of the opt-out has recently become a focus of attention once more due to this new impetus around Article 42.7, as well as EU defence initiatives such as PESCO, the European Defence Fund, and the European Peace Facility. However, the opt-out is likely here to stay. Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, leader of the Social Democratic Party, has emphasised that she views opt-outs as “the bedrock of Denmark’s position” in the EU, and that her government sees no reason to reconsider the opt-out on defence. The government has also been significantly more sceptical of the EU than its predecessors have, all of which emphasised their ambition to end the defence opt-out when the time was right. But these governments have been unsuccessful whenever they have held a referendum on opt-outs – including those on the eurozone in 2000 and on justice and home affairs in 2015.

Traditionally, Danish governments have been restrictive in their application of the defence opt-out. But, curiously, the current government seems to be exploring ways to do more within the boundaries of the measure. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, because the opt-out is likely here to stay, the government wants to find a pragmatic solution in which Denmark can increase its room for manoeuvre on EU defence cooperation. Secondly, the EU has significantly strengthened its defence cooperation in recent years, and done so in a manner that allows Denmark to take part in many new initiatives. The country seems compelled to retain the opt-out as a sovereignty guarantee while participating in this expanded defence cooperation to some extent. Denmark wants to have its cake and eat it too.

From neutrality to activism: Finland and EU defence

- EU member since: 1995

- Neutral since: 1955 (changed status from neutrality to military non-alignment in the context of EU accession)

- Population: 5.6 million

- Current defence spending as a share of GDP: Approximately 1.9 per cent

- Number of troops: 12,300 active and 280,000 reserve

The steady decline of neutrality and non-alignment

Finland’s accession to the European Union in 1995 marked a fundamental change in its foreign policy. From the mid-1950s to the early 1990s, the country pursued a policy of neutrality that put strict limits on its involvement in Western economic and political cooperation. More importantly, neutrality helped Finland to maintain a degree of distance from the Soviet Union. It strengthened Finland’s international position in the challenging cold war environment, providing the country with more room for manoeuvre during a time when Finnish foreign policy was largely conditioned on Moscow’s behaviour. Finnish neutrality was, above all, a political instrument – but it was internalised by Finnish policymakers and voters alike.

However, the Finnish foreign policy leadership quickly realised that Finland’s previous definition of neutrality had limited use after the end of the cold war – and that neutrality was largely incompatible with the nature and requirements of EU membership. As a result, Finland began to pursue a less restrictive policy of military non-alignment.

When it joined the EU, Finland expressed its full commitment to, and supported the development of, the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). Moreover, during its first years of EU membership, Finland sought to shape the EU’s nascent security and defence policy. Despite its abandonment of strict neutrality, Finland was still averse to the (faint) possibility that the union’s security and defence policy would develop in the direction of territorial defence. Thus, Finland, along with Sweden, advocated a stronger EU role in crisis management – both to pre-empt the potential rise of a more traditional defence agenda within the EU and to demonstrate that the two countries were not neutral oddballs but rather fully fledged and active EU members.

The evolution of the CFSP, including the Common Security and Defence Policy, pushed Finland to re-evaluate its defence status in the late 2000s. The Lisbon Treaty, which entered into force in December 2009, contained both the mutual assistance clause – Article 42.7 – and the solidarity clause. The introduction of Article 42.7 in particular implied that EU membership could entail territorial defence commitments. In 2007, anticipating the treaty, Finland’s new centre-right government came up with a definition of Finland’s defence status that better reflected the realities of the EU: a country that does not belong to any military alliance. The differences between the two definitions may appear to be purely semantic – indeed, military non-alignment and the newer definition are used interchangeably in the domestic debate. However, the change of status conveyed an important message: an EU member cannot be fully non-aligned politically or militarily.

Despite its new status, Finland’s policy remained largely unchanged. However, Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014 prompted a major shift in Finnish security and defence policy. Although this Russian aggression in Ukraine was not a sufficient incentive for Finland to seek NATO membership, it significantly increased the country’s appetite for robust defence cooperation. Since 2014, Helsinki has updated old defence partnerships and forged new ones. The most important frameworks for Finland are its bilateral partnerships with both Sweden and the United States, the Nordic Defence Cooperation, its close partnership with NATO, and the security and defence dimension of the EU. In addition to these frameworks, Finland has joined new European ‘minilateral’ defence formats: the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force, the French-driven European Intervention Initiative, and the German-initiated Framework Nations Concept.

This flurry of defence activity has created a new paradigm in which Finland uses such cooperation not only to strengthen its defence and deterrence but also to create the necessary preconditions for operational cooperation in times of crisis and war. Therefore, Finland has an alliance policy in all but name. In the last decade and a half, there has been a fundamental change in the practical implications of non-membership of any military alliance – as a result of which Finland has almost entirely stopped referring to this status in official foreign policy communications.

Finland as an EU defence activist

Finland’s pursuit of closer and deeper military collaboration with its partners has influenced its approach to the EU’s defence agenda. The paradigmatic change in Finnish defence thinking coincided with the EU’s efforts to boost its credibility as a security and defence actor following a European Council meeting in 2013 and, above all, the Brexit vote in 2016. Consequently, the formerly neutral state has become one of the most vocal advocates of the EU’s security and defence efforts – and seems to have cast aside any residual neutralist sentiments and reservations. Today, Finland would readily accept a stronger EU role in territorial defence – in striking contrast to the country’s position in the 1990s and 2000s.

Helsinki’s enthusiasm for EU defence manifests in its strong support for recent initiatives such as the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence, the European Defence Fund, the Military Planning and Conduct Capability, Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), and the Strategic Compass. At the same time, these initiatives have not attracted significant attention in the country beyond a small circle of experts. Moreover, the initiatives have limited value to Finnish defence in the short term, as they neither strengthen Finland’s deterrence nor facilitate operational cooperation between EU member states’ armed forces – at least not in the context of territorial defence.

Two areas stand out in Finland’s efforts to shape the EU security and defence agenda. Firstly, Finland has tried to build up awareness of hybrid threats in the EU context, presenting itself as a “hybrid-savvy” state with a functioning whole-of-society approach to security. The most tangible example of Finland’s activity in this field is the establishment in 2017 of the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, based in Helsinki. To date, 28 states – including Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the US – have joined the centre, which also fosters cooperation between the EU and NATO. Countering hybrid threats featured prominently on Finland’s agenda for its presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2019. During the presidency, EU ministers and working parties conducted scenario-based policy discussions on hybrid threats.

Secondly, Finland has often reminded its fellow member states of the importance of Article 42.7. The president of Finland has even called the clause “the true core of European defence”. According to Finnish thinking, the EU is a “security community” characterised by mutual solidarity and Article 42.7 is a key element of the community. The 2020 Government Report on Foreign and Security policy states that “solidarity is of high security policy importance for Finland … Here, solidarity means that Finland will receive aid and assistance at its request, and that Finland will provide aid and assistance to another Member State or the European Union if necessary.” By stressing the importance of Article 42.7, Finland does not seek to replace or replicate NATO’s Article 5. Rather, Finnish policymakers have suggested that the former could apply in a situation in which, for example, an EU member state becomes a victim of serious hybrid influencing. However, there has been no domestic debate about the scenarios in which Finland would seek to invoke Article 42.7.

In addition to rhetorical advocacy of the clause, Finland has reportedly bent over backwards to include references to Article 42.7 in key EU documents, such as the Council of the EU decision establishing PESCO. When France, in the aftermath of the 2015 Paris terrorist attacks, invoked Article 42.7 to request assistance from other EU members, Finnish policymakers recognised an opportunity to set an important precedent. Helsinki swiftly decided to provide assistance to Paris, albeit indirectly. Most notably, Finland deployed additional troops to the UN Interim Force in Lebanon, thereby freeing up French troops for other tasks.

Finland’s advocacy of Article 42.7 reflects the evolution of its attitude towards EU defence since the early 2000s. When the mutual assistance clause emerged in the Convention on the Future of Europe, Finland did not oppose the idea of it per se but wanted to make sure that it would not involve automaticity in the provision of military assistance. However, after the EU eventually found an acceptable formulation, Finnish policymakers quickly adopted a rather positive stance on the clause and the idea of European solidarity more broadly. The Finnish Parliament’s foreign affairs committee, for example, stressed the article’s importance as a deterrent and called on it to amend legislation on providing and receiving military assistance. The government adopted the relevant legislative package in 2017, driven partly by the French request to activate Article 42.7 in 2015 and by advancing defence cooperation with Sweden.

Despite its active and positive approach to the evolution of the security and defence agenda in Europe, Finland has not articulated a clear vision of how this process should continue. Helsinki has adopted a somewhat ambiguous position in the lively debate on ‘strategic autonomy’ in the EU. Finland is strongly in favour of increasing Europe’s capacity to act in foreign, security, and defence matters. In the Finnish view, this should involve not only the EU but also initiatives such as the Joint Expeditionary Force, the Nordic Defence Cooperation, and the bilateral defence cooperation between Finland and Sweden. However, investing in autonomy should not mean weakening Europe’s global partnerships – particularly the transatlantic relationship. Instead, it should be about the EU and European countries taking more responsibility for their own security, thereby also heeding the US calls for greater burden sharing. Finland is less enthusiastic about the broadened interpretation of strategic autonomy, which extends to industrial policy and trade. With its small, export-orientated economy, Finland is wary of initiatives with protectionist elements. According to the Finnish government’s recent report on EU policy, the EU’s strategic autonomy “must be based on the development of [the union’s] own strengths, fair competition and participation in the global economy as well as on a more resolute promotion of the EU’s values and interests and on responsibility in external action”.

Future avenues of cooperation

Finland will likely continue to develop its new approach to defence cooperation. The country’s geographic location next to an assertive Russia ensures that it has a lasting incentive to maintain a relatively strong defence capability. Given the power asymmetry between Finland and Russia, and the rising costs of defence materiel, it would be almost impossible for Helsinki to sustain a credible defence posture without extensive defence partnerships and networks. The EU’s evolving defence tools and other European initiatives will be central to the set of defence collaborations Finland uses to strengthen deterrence and prepare to respond to crises and conflicts. Finland is too small a player to shape the overall direction of the EU security and defence agenda, but it can lend its support to the initiatives of bigger member states, most notably France and Germany.

Despite its manifest willingness to intensify military cooperation, Finland is unlikely to re-evaluate its current status and join NATO in the short term – particularly given that it already has a host of interested partners that are willing to engage with it in developing deep, mutually beneficial cooperation. Significantly, Finland’s current model also serves NATO’s interests. Most Finns oppose NATO membership. And Finnish policymakers worry that the costs of Russian retaliation to Finland joining NATO would outweigh the benefits of doing so. Nevertheless, NATO membership will continue to be an option for Finland in the future, as Finnish policymakers are eager to stress. If Russia became increasingly aggressive or Sweden changed its attitude towards NATO membership, Finland would be forced to reconsider its current policy.

Currently, Finland’s official status as a non-member of a military alliance does not limit the country’s appetite for developing defence cooperation, be it the EU’s defence efforts or collaboration in smaller formats. A more militarily capable Europe would undoubtedly enhance Finland’s security. And Helsinki is ready to do its fair share to achieve that goal.

Committed neutrality: Ireland’s approach to European defence cooperation

- EU member since: 1973

- Neutral since: 1938 (Agreement with the UK)

- Population: 4.9 million

- Current defence spending as a share of GDP: Approximately 0.3 per cent

- Number of troops: 8,750 active and 4,050 reserve

Military neutrality has long been a core concept in Irish foreign policy. While this policy is characterised by “non-membership” of military alliances and “non-participation in common or mutual defence arrangements”, Ireland has fulfilled its commitments to international peace and development efforts. As recently noted by the chair of the EU Military Committee, General Claudio Graziano, Ireland’s neutrality has not prevented it from fulfilling its responsibilities as part of UN- and EU-led missions. The EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) has allowed Ireland to engage in a combination of cooperation and pragmatic abstention, in line with national positions.

Ireland’s neutrality is not enshrined in its constitution or laws, or in any international treaty. The country’s 2020 Programme for Government sets out a policy of “active military neutrality” that allows for the continuation of both a flexible and participative multilateral approach.

Ireland’s military neutrality gained political prominence during the second world war under Taoiseach Eamon de Valera. He announced on 19 February 1939 that Ireland would be neutral in the case of war. The Anglo-Irish agreement on trade, finance, and defence, which he signed on 25 April 1938 with then UK prime minister Neville Chamberlain, was a significant development for Irish neutrality. As a trade agreement to end the economic war with Britain, it formalised the return of all port, aviation, and other defence facilities to the Irish government.

Several factors determined Ireland’s neutrality. In the context of Anglo-Irish relations, de Valera viewed neutrality as a means of self-determination and independence from British foreign policy. In the global context, the Irish government considered neutrality to be a pragmatic approach that kept the state out of any potential war – as was necessary given Ireland’s insufficient defence and military structures.

Neutrality for Ireland has always meant non-membership of military alliances. The fact that Ireland is not a member of any such organisation has bolstered its credentials as a significant contributor to UN peacekeeping. Ireland opted not to join NATO when it was formed in 1949 because of several considerations, including a degree of discomfort about military cooperation with the UK while the two countries disputed the constitutional status of Northern Ireland.

Current engagement with European defence efforts

Engagement with the European Union is a hallmark of Irish defence policy, as stated in Ireland’s 2019 White Paper on Defence. Neutrality is no obstacle to Ireland broadly participating in the CSDP. The country has been involved in several EU defence initiatives, including Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), the Coordinated Annual Review of Defence (CARD), the European Defence Fund (EDF), and military and civilian missions led by the bloc. Today, all Irish decision-making on the CSDP turns on a so-called ‘triple lock’ mechanism. In line with the Defence Acts, the Irish Defence Forces cannot be deployed to any conflict zone or CSDP mission without the approval of the UN, the government, and the Dail, the lower house of parliament.

On PESCO, Ireland participates in the Upgrade of Maritime Surveillance project. It is an observer on nine more PESCO projects, including military deployments for disaster relief, medical training, and cyber threats. The Irish Department of Defence and the Defence Forces continuously assess the value for Ireland of further participation in PESCO projects. Ireland participates fully in the European Defence Agency’s annual CARD, a review of military capabilities that is open to all member states on a voluntary basis. Ireland also contributes to the European Defence Fund, which provides a means to better coordinate and otherwise enhance national investments in defence. Simon Coveney, the minister for foreign affairs and minister for defence, has underlined the value of the EDF in helping increase “output” and jointly developing defence technology and equipment that states could not create alone.

As an off-budget mechanism, the European Peace Facility allows the EU to provide assistance to CSDP missions and operations. In negotiations to set up the facility, Ireland and like-minded states ensured that it included a safeguard to “constructively abstain” from assistance measures that involve lethal equipment. This approach reflected Ireland’s interests and the 2020 Programme for Government, which stated that Ireland “will not be part of decision-making or funding for lethal force weapons for non-peacekeeping purposes”. The EDF – which falls under the EU’s 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework – does not provide funding for the development of lethal autonomous weapons, which are prohibited under international law. Ireland has consistently stated that weapon systems should remain under “meaningful human control”.

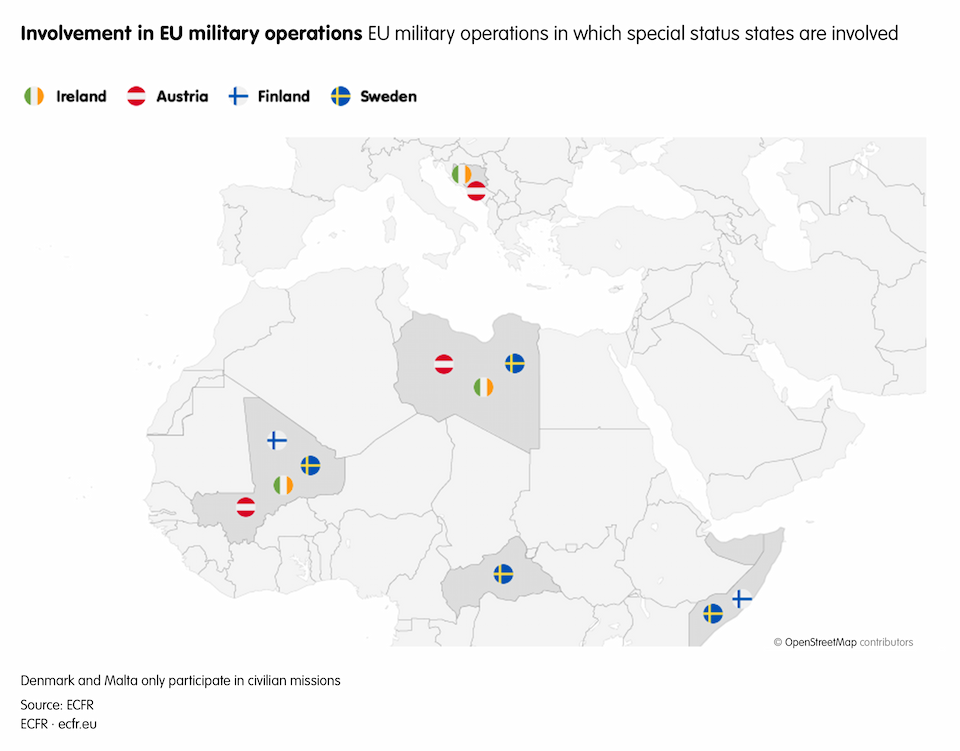

As a special status country, Ireland has made a strong commitment to EU military and civilian missions. This includes deployments of Defence Forces personnel to Operation Irini in the eastern Mediterranean, the EU Training Mission (EUTM) in Mali, and Operation Althea in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ireland’s contributions also include the appointment of a senior Irish officer as the operational commander of the EU Military Operation in Chad and the Central African Republic in 2007 and another as mission commander of EUTM Somalia in 2011 and 2013. In EU civilian missions, Ireland has deployed experts to Niger, Somalia, Kosovo, Georgia, Iraq, and Ukraine.

While Ireland is not a NATO member, it has participated in the NATO Partnership for Peace programme and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council since 1999. It also joined the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in 2019.

Ireland’s view of EU defence ambitions

From an Irish perspective, Article 42.7 of the Lisbon Treaty did not turn the EU into a defence union as it avoided the development of a “common defence”. While the EU mutual assistance clause allows member states to provide “aid and assistance” in the case of an attack, it is intergovernmental and involves bilateral consultations with different states. Ireland, Finland, and Sweden can preserve their neutrality or military non-alignment in this framework.

In an Irish referendum on the treaty in June 2008, 53.4 per cent of participants voted ‘no’ after campaigners argued that that it could undermine Ireland’s military neutrality, making reference to Article 42.7. The European Council adopted in July 2009 a decision that provided guarantees to Ireland on defence matters. They included the discretion for countries with a traditional policy of neutrality “to determine the nature of aid or assistance” in the case of armed aggression on the territory of another member state. Another safeguard for Ireland included a requirement for a unanimous decision of the European Council for “any decision to move to a common defence”.

This safeguard clause under Article 42.7 addressed the concerns of Irish voters about safeguarding the traditional policy of neutrality. As part of this mutual assistance clause, the article is prefaced by the statement that it “shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain Member States”. The Italian proposal to include this language at the drafting stage was preferable to an opt-in provision, which would have required a full commitment to the mutual assistance clause.

The agreed mutual assistance clause involved a broad compromise between three groups of states: those seeking mutual defence; those protecting a traditional policy of neutrality and non-alignment (Ireland, Austria, Finland, and Sweden); and those keen not to affect NATO. Importantly, it illustrated how the CSDP accommodated special status countries. In a second Irish referendum on the Lisbon Treaty, held in October 2009, 67.1 per cent of participants voted ‘yes’.

When France invoked Article 42.7 following the Paris terrorist attacks in November 2015, Ireland supported this decision and offered to provide any assistance that it could, in line with the safeguard clause. There was only a limited public debate to the response under Article 42.7 in Ireland. But the country increased its contribution to EUTM Mali in mid-June 2016 and June 2017, with the result that it eventually provided a total of 20 personnel to the mission.

The debate on European ‘strategic autonomy’ in Ireland is mainly an expert-led discussion. While the term still lacks resonance in the public debate, the Irish government has shown an interest in discussing strategic autonomy (even though the meaning of the term is contested). Views on EU defence policy and neutrality vary between Fine Gael, Fianna Fail, the Green Party, and Sinn Fein. Fine Gael and Fianna Fail, partners in the coalition government, favour EU defence cooperation within existing safeguards, which they see as preserving Ireland’s special status. The Green Party, another partner in the government, opposes an expansion of PESCO in areas “not compatible with Ireland’s non-aligned and peacekeeping defence tradition”. Sinn Fein adopts a narrow interpretation of neutrality that opposes increased EU defence efforts.

Future deliberations

There is no public debate on invoking Article 42.7 in Ireland but, in principle, the country could call on other EU member states to provide security assistance in extreme circumstances for air policing, cyber defence, and maritime surveillance. However, Ireland’s preference for addressing security matters bilaterally could preclude such a decision.

There is relatively little prospect of armed aggression on Ireland’s territory, due to the character of emerging threats the country faces. Nonetheless, Ireland’s growing role as a hub for data centres following Brexit, and the implications of a cyber attack for global security, suggest that country should develop greater cyber defence capabilities. This is reflected in Ireland’s cyber security strategy for 2019-2024, which states that there is a “clear need” to develop engagement with cyber security across the EU. Analysts Sara Myrdal and Mark Rhinard argue that cyber attacks could, in theory, trigger both Article 42.7 and the solidarity clause (Article 222 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union). However, the possibility of invoking either of these articles in the case of cyber attacks has not been widely discussed in Ireland.

While Ireland’s special status may evolve, it is unlikely to abandon its policy of neutrality in the short term. Nonetheless, the country continues to cooperate with other member states effectively on CSDP initiatives via safeguards and constructive abstentions.

The views expressed in this essay are those of the author, and not the Institute of International and European Affairs.

Pragmatic neutrality: Malta’s view of EU defence

- EU Member since: 2004

- Neutral since: 1987 (enshrined in the Constitution and Malta’s EU accession treaty)

- Population: 515,000

- Current defence spending as a share of GDP: approximately 0.6 per cent

- Number of troops: 1,700 Active + 260 Reserve

Malta wrote neutrality into its Constitution in 1987 following negotiations between the Nationalist Party and the Labour Party – the only political groups to have won seats in the national Parliament since independence in 1964, and in the European Parliament since Malta joined the European Union in 2004.

Article 1.3 of the Constitution specifies that “Malta is a neutral state actively pursuing peace … by adhering to a policy of non-alignment and refusing to participate in any military alliance.” The article defines neutrality as precluding foreign military bases on Malta’s territory and foreign forces’ use of military facilities there – except at the request of the Maltese government in relation to decisions by the UN Security Council, the need for self-defence, or threats to Malta’s independence, sovereignty, and neutrality. The Constitution allows for the deployment of small contingents of foreign troops to assist “in the performance of civil works or activities”. Maltese shipyards are permitted to construct military vessels and repair those that are not in combat. Nonetheless, the shipyards are off-limits to the military vessels of Russia, as the successor of the Soviet Union, and of the United States.

The inclusion of the neutrality clause in the Constitution stemmed from a review a parliamentary select committee launched in 1985, amid a political crisis. Following several meetings behind the scenes, the government announced in 1987 an agreement that consisted of two elements: the neutrality clause and a provision that, in any general election, a party that obtains more than 50 per cent of the first-count votes is entitled to an absolute majority of parliamentary seats. The latter provision was intended to avoid a repeat of the 1981 election result, in which the Labour Party won an absolute parliamentary majority with fewer votes than the Nationalist Party. This form of revision, which excludes the people from the debate, has become the only means through which to change the Constitution.

Neutrality and EU membership

Malta embarked on a policy of neutrality and non-alignment following the closure of UK military bases on its soil in 1979. Parliament approved a solemn declaration of neutrality on 14 May 1981. Malta cut and pasted this declaration and the 1987 neutrality clause inserted into the Constitution from the bilateral Neutrality Treaty it concluded with Italy in 1980.

A year later, Malta reached a neutrality accord with the Soviet Union, which expressed “its readiness to consult with the Government of Republic of Malta (GRoM) on questions directly affecting the interests of the two countries, including the neutral status of Malta, and in case of situations arising which create a threat to peace and security or the violation of international peace, will also be prepared, as necessary, and at the request of the GRoM and by agreement between the parties, to enter into contact with it so as to coordinate their positions in order to remove the threat or to establish peace.”

During its EU accession negotiations, Malta confirmed that its neutrality would not be an obstacle to the development of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) or the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). But neutrality became a highly charged and symbolic issue in the national debate on membership: the Labour Party argued that EU membership undermined Malta’s neutrality, while the Nationalist Party disagreed. In Declaration 35 of the Treaty of Accession, Malta affirmed its commitment to the CFSP as set out in the Treaty on European Union. The declaration also affirmed that Malta’s participation in the CFSP did not prejudice its neutrality because, as the treaty specified, any European Council decision to move to a common defence would have to be unanimous and had to “be adopted by the Member States in accordance with their respective constitutional requirements”.

The government described Declaration 35 as an additional safeguard that was necessary to allay public concerns, given that neutrality is an integral part of the Maltese identity. The Labour Party, however, stressed that EU treaties would oblige Malta to support the CSDP in good faith and that “constructive abstention” was unlikely to work well.

Mutual defence

The Labour Party was probably the first to highlight the fact that mutual defence could conflict with Malta’s definition of neutrality. Members of the EU initially raised the idea of mutual defence in 2002 at the Convention on the Future of Europe – which both Maltese political parties attended. And a mutual defence clause featured in the draft Treaty Establishing a Constitution for Europe.

Following Malta’s accession to the EU, the Labour Party began to support membership of the bloc, helping create a national consensus on the issue. However, the two parties adopted different stances on neutrality. When in July 2004 Malta announced that it would join the European Defence Agency, the Labour Party retorted by pledging to leave the agency as soon as it was regained power (a commitment that it would quietly forget). However, Malta encountered other difficulties in the CSDP: since it had suspended its participation in NATO’s Partnership for Peace in 1996, and did not rejoin the initiative until 2008, it could not fully participate in the EU-NATO Berlin+ arrangements in 2004. After 2008, the country began to participate in several CSDP missions. While Malta did not join Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) in 2018, it maintained the option of joining later.

The need for constitutional changes

In the last two decades, the Nationalist Party and the Labour Party have reached a consensus on the need to rewrite the neutrality provisions in the Constitution, but neither has tabled a proposal for how to do so. Although both parties accept neutrality, their conceptions of it differ: the Labour Party does not want Malta to fully participate in what it perceives to be the further militarisation of the EU, while the Nationalist Party is against “neutralisation” and favours “active neutrality”. As a Nationalist Party deputy prime minister wrote in 2010, “being neutral does not mean, as Churchill once remarked, being neutral between the fire and the firefighters”.

The position Malta adopted during the 2011 Libyan crisis probably satisfies both parties as a model for future engagement. Then, Malta did not join NATO’s campaign or allow the alliance to use its territory for military operations, but instead focused on humanitarian missions. At the same time, the country did not refrain from criticising the Qaddafi government for its violence against civilians. And it publicly supported an EU Council statement that the regime had lost its legitimacy. In August 2011, Malta recognised the Benghazi-based Libyan Transitional Council as the legitimate government of the Libyan people.

In the shadow of Article 42.7

The apparent contradiction between neutrality and EU mutual defence characterised Malta’s parliamentary debates both on the draft Treaty Establishing a Constitution for Europe and the Lisbon Treaty. In 2005 the Labour Party, which had just adopted a more pro-EU stance and thereby won three seats in the European Parliament, opted for the ratification of the draft treaty. Simultaneously, however, it still wanted to preserve its support for neutrality and win over internal opponents of ratification. Labour’s parliamentary group agreed to support the draft treaty in Parliament, but to subject the vote to a condition that a Labour government would reverse any decision that it saw as undermining neutrality. A general conference of the party delegates endorsed the parliamentary group’s position, based on the understanding that the Constitutional Treaty “does not prejudice Malta’s constitutional neutrality”.

The group quoted legal advice indicating that the safeguards on neutrality that Malta had secured in the Accession Treaty were still valid under the draft European constitution. The group voted in favour of the Constitutional Treaty on the condition that, as it spelt out in a document submitted with the vote, “from a legal standpoint, Malta will not be bound in any way by commitments to mutual or common defence … Malta will not be obliged to join any effort aiming at the creation of a European Army. The participation of Maltese contingents from the Armed Forces in CSDP missions will continue to be defined in accordance with the provisions of the Maltese Constitution.”

In a 2008 parliamentary debate, the Labour Party voted in favour of the Lisbon Treaty’s ratification but expressed the same reservations that it had in 2005.

Article 42.7 in practice

When France invoked Article 42.7 following the Paris attacks of November 2015, the Maltese prime minister made a lengthy statement in Parliament dwelling mostly on the implications for Malta’s security and the safety measures needed to prepare for the Commonwealth Summit in Valletta later that month. A few days later, the government stated that, if France specifically asked Malta for help, the latter was ready to meet this request in line with the Maltese Constitution and EU treaties. The government added that it “had been advised by the Advocate General that the fact that an EU member state requests help on the basis of provisions in the Lisbon Treaty does not entail or does not necessarily lead to actions that infringe the neutrality clauses as protected by the Maltese Constitution.”

European strategic autonomy

The idea of ‘strategic autonomy’ has not caught on in Malta’s public debate, although it has been broached in some of the local academic literature. References to the concept in official ministerial statements relate to economic and trade objectives, but not to political or defence integration.

Conclusion