Germany Charts its Place in the World, But Struggles to Adapt to Changing Realities

For more than 140 days, Germany, the world’s fourth-largest economy and de facto leader of the EU, has been without an elected government. Since the federal elections in late September, the six parties voted into the Bundestag have been unable to form a government. However, you could be forgiven for not being aware of this, since the former government — with Angela Merkel as chancellor — continues to manage daily politics. In early February, Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democrats (SPD) finally agreed on a coalition treaty. If this coalition is indeed formed (SPD members still need to agree), Germany will finally get a new government — though it will still be led by Merkel.

The entertainment value of this process has been unusually high for German politics. There have been “dwarf uprisings,” a chancellor candidate who managed to lose it all, coalition options named after Caribbean islands, and quite a lot of other drama, with the possibility for more. More importantly, however, the coalition treaty that has just been agreed on provides interesting insights into in the broader conversation in Europe about transatlantic relations and the European Union’s defense posture. With the United States increasingly considered an unreliable partner, the new government wants Germany “to remain transatlantic” but “become more European.” Rising security threats and uncertainty about the American security umbrella have led to a more intense debate about Germany’s defense capabilities, and the agreement proclaims, accordingly, that it will raise defense spending somewhat. But the pacifist country struggles to commit to — and finance — real German and European military capabilities. Germany’s coalition agreement highlights how difficult it will be for European leaders to truly deliver on rhetoric about moving away from U.S. guarantees and building up national and collective defense capabilities at a time of limited budgets and rising threats.

United States Yes, Trump No

It is not news that Germany is not happy with President Donald Trump, who stands for beliefs that many Germans don’t share. Sixty-seven percent of Germans think protecting the climate should be a priority of German foreign policy. Germans’ confidence in the U.S. president “to do the right thing when it comes to international affairs” has dropped from 86 percent under Obama to 11 percent under Trump. The nascent coalition government has made an effort to have a, gender-balanced cabinet (though some personnel changes are still possible) — a decision in stark contrast with the numerous sexism allegations against the Trump administration. Merkel, on the occasion of Trump’s election, underlined that she was happy to work with the United States — on the basis of common values of “democracy, freedom and respect for the law and the dignity of man, independent of origin, skin colour, religion, gender, sexual orientation or political views.”

Some comments in the coalition agreement are clearly aimed at the American president: “We want fair and resilient trade relations with the US. Protectionism is not the right way,” it states. The government aims to respond to “the fundamental change” taking place in America by talking not only to the U.S administration, but also Congress and the states — clearly an effort to circumvent the White House. Most telling, however, is a seemingly inconspicuous phrase: “We are linked with the US and Canada in a strong community of values and interests.” Similar phrases have been in previous coalition agreements, but the inclusion of Canada is new. While continuing to try to keep the United States as a key partner, Germany is also looking elsewhere. When it comes to upholding the international liberal order, Justin Trudeau’s Canada appears to be a safer bet than Trump’s America. These views are not unique to the new government, but, rather, a product of changed transatlantic relationship that began under Trump. However, the new coalition agreement puts these changes in black and white.

United Europe

The new government wants Germany to “become more European.” The coalition agreement itself is entitled “A new beginning for Europe. A new dynamic for Germany. A new solidarity for our country.” It dedicates its very first section to Europe, noting that “Germany owes Europe endlessly.” Europe has become the legitimizing narrative for this coalition that has been neither party’s first choice. Any German government was expected to be highly supportive of the European Union, but the tone of this agreement is even more positive than expected. It’s also not just warm words: The government declared its readiness to contribute more to the E.U. budget — important in the context of Brexit, since the union loses a net contributor with the United Kingdom leaving. This stronger love for Europe is partly a reaction to changes in the United States. “New priorities in the US […] show clearly: More than before, Europe has to take its fate into its own hands.”

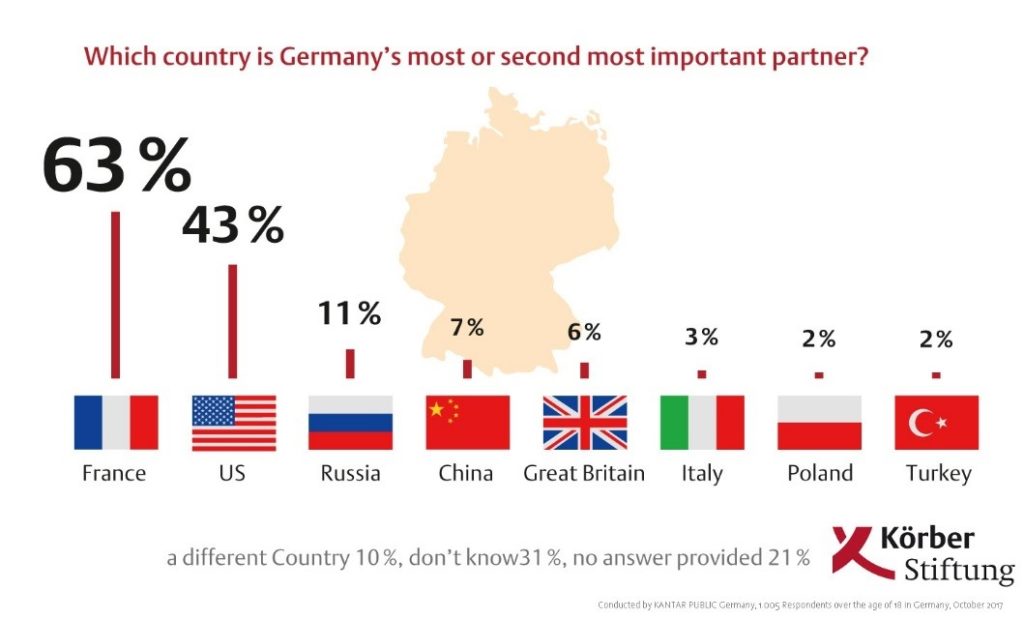

If America’s star is sinking, another partner’s star is rising: France. France is mentioned 12 times in the document — more than any other country, and up from only three times in the 2013 coalition treaty. The German public agrees with this approach — in a recent poll, France, for the first time, overtook the United States as the most important partner for Germany. Many projects proposed by French President Emmanuel Macron are discussed in the coalition agreement, from a European monetary fund to efforts to involve citizens in public dialogues on European reform. Commentators quickly crowned Macron the winner of the coalition, although I would caution against popping Champagne in the Elysée Palace too soon.

German and European defense

The German coalition treaty reaffirms the plan to increase the defense budget from €38.5 billion to €42.4 billion by 2021, noting that if tax revenue is higher than expected, the Bundeswehr would be the first to receive more money. This increased defense spending is pegged to expenditures on development cooperation and diplomacy, meaning the two budgets are to rise simultaneously — an approach that illustrates well Germany’s comprehensive approach to security and cautious approach to anything military.

The impact of the defense budget increase, however, should not be overstated. It would barely increase Germany’s spending in relation to its GDP, a key NATO benchmark. Currently, Germany spends 1.2 percent of its GDP on defense, a long way from the 2 percent NATO goal that Germany agreed to reach by 2024. Whether or not the NATO goal is mentioned in the coalition agreement is, strangely, a matter of debate between the coalition partners — the agreement mentions the “NATO target corridor,” but SPD members of parliament have denied that this is in fact a reference to the 2 percent goal, a reading that CDU members object to. Also, given the dire state of the German armed forces, the budget rise is expected to be taken up by equipment repairs and pay rises. Even so, there has been criticism from the left that the parties have agreed to form a coalition “for war and rearmament.” (France, in the meantime, announced that it would raise its defense budget somewhat more substantially from €34.2 billion to € 44 billion by 2023.)

The agreement also addresses German contributions to European defense spending. Europe has long struggled to build effective defenses against security threats. The Munich Security Conference estimates that Europe (EU-28 + Norway) would require an additional annual budget of $10 to 20 billion just to close its interconnectedness and digitization gaps, and not even the larger powers are able to quickly mobilize forces as small as single armored brigades. While Russia is increasing its defense spending and modernizing its forces, Europe remains reticent to spend more.

In the last year, however, there has been quite some movement in the area of European defense. A combination of scares (notably Brexit and Trump’s election), threats (terrorism and an assertive Russia), and increased enthusiasm to do more on the European scene in general (thanks to Macron, and, somewhat counterintuitively, Brexit) has let the EU-27 to think more seriously about their security. For instance, member states agreed upon PESCO, the Permanent Structured Cooperation under whose umbrella joint defense projects can be developed. In line with these sentiments, the new German government aims to increasingly “plan, develop, acquire, and use” military capabilities on the European level. It cautiously suggests that this should lead to military equipment that is uniform throughout Europe — at the moment, Europe has 17 main battle tank types, where the United States has one, and 29 different destroyers and frigates, compared to America’s four. While these are promising intentions, many problems remain, including that if European countries did this, they could no longer actively support their national defense industries.

The coalition agreement also speaks of moving closer toward an “Army of the Europeans.” But it remains unclear what this means in practice. Macron similarly had proposed the eventual formation of a European intervention force. But without more concrete details, these proposals remain dreams.

The new German government is trying to navigate a more hostile world, in which the transatlantic relationship does not appear to be what it once was. The coalition aims to keep its transatlantic ties, all the while hedging against losing them by building up European unity and capabilities. There is willingness to do more on defense and security, but no unifying vision to make it happen and no convincing proposal to deal with problems such as diverging European interests and threat perceptions. Hopefully the next government, once in power, will spend some time developing more concrete proposals and filling the ideas about a stronger and more capable Europe with content. Not having an elected government has hindered European reform in particular. The new government now has to prove that it can deliver what Europe is waiting for.

Ulrike Franke is a Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), currently based in Berlin. In ECFR’s New European Security Initiative, she works on German and European security and defense policy, and focuses on new military technologies such as drones and artificial intelligence.

Image: U.S. Air Force/Joshua Strang